A Slight Re-Telling of the David and Goliath Story: Surprising Power Dynamics in Proxy Relationships Ruiyang Wang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria Cvdpv2 Outbreak Situation Report # 17 10 October 2017

Syria cVDPV2 outbreak Situation Report # 17 10 October 2017 cVDPV2 cases in Deir Ez-Zor, Raqqa and Homs governorates, Syria, 2017 Summary New cVDPV2 cases this week: 1 Total number of cVDPV2 cases: 48 Outbreak grade: 3 Infected governorates and districts Governorate District Number of cVDPV2 cases to date Deir Ez-Zor Mayadeen 39 Deir Ez-Zor 1 Boukamal 5 Raqqa Tell Abyad 1 Thawra 1 Homs Tadmour 1 Index case Location: Mayadeen district, Deir Ez-Zor gover- norate Onset of paralysis: 3 March 2017, age: 22 months, vaccination status: 2 OPV doses/zero The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or IPV acceptance by the United Nations. Source: Syrian Arab Republic, Administrative map, DFS, United Nations 2012 Most recent case (by date of onset) Key highlights Location: Mayadeen district, Deir Ez-Zor gover- norate One (1) new case of cVDPV2 was reported this week from Mayadeen district, Deir Onset of paralysis: 19 August 2017, age: 19 Ez-Zor governorate. The case, a 19-month-old child with no history of polio months, vaccination status: zero OPV/zero IPV vaccination, had onset of paralysis on 19 August. Characteristics of the cVDPV2 cases The total number of confirmed cVDPV2 cases is 48. Median age: 16 months, gender ratio male- female: 3:5, vaccination status: The second immunization round for Raqqa commenced 7 October. mOPV2 is IPV: 9 cases (19%) received IPV being administered to children 0-59 months of age, and IPV to children aged OPV: 33% zero dose, 46% have received 1-2 between 2-23 months. -

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

John J. Mearsheimer: an Offensive Realist Between Geopolitics and Power

John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power Peter Toft Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Østerfarimagsgade 5, DK 1019 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] With a number of controversial publications behind him and not least his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John J. Mearsheimer has firmly established himself as one of the leading contributors to the realist tradition in the study of international relations since Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. Mearsheimer’s main innovation is his theory of ‘offensive realism’ that seeks to re-formulate Kenneth Waltz’s structural realist theory to explain from a struc- tural point of departure the sheer amount of international aggression, which may be hard to reconcile with Waltz’s more defensive realism. In this article, I focus on whether Mearsheimer succeeds in this endeavour. I argue that, despite certain weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s theoretical and empirical work represents an important addition to Waltz’s theory. Mearsheimer’s workis remarkablyclear and consistent and provides compelling answers to why, tragically, aggressive state strategies are a rational answer to life in the international system. Furthermore, Mearsheimer makes important additions to structural alliance theory and offers new important insights into the role of power and geography in world politics. Journal of International Relations and Development (2005) 8, 381–408. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065 Keywords: great power politics; international security; John J. Mearsheimer; offensive realism; realism; security studies Introduction Dangerous security competition will inevitably re-emerge in post-Cold War Europe and Asia.1 International institutions cannot produce peace. -

The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community

STUDY The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community AZIZ NAKKASH March 2013 n There are many ways of understanding Alawite identity in Syria. Geography and regionalism are critical to an individual’s experience of being Alawite. n The notion of an »Alawite community« identified as such by its own members has increased with the crisis which started in March 2011, and the growth of this self- identification has been the result of or in reaction to the conflict. n Using its security apparatus, the regime has implicated the Alawites of Homs in the conflict through aggressive militarization of the community. n The Alawite community from the Homs area does not perceive itself as being well- connected to the regime, but rather fears for its survival. AZIZ NAKKASH | THE ALAWITE DILEMMA IN HOMS Contents 1. Introduction ...........................................................1 2. Army, Paramilitary Forces, and the Alawite Community in Homs ...............3 2.1 Ambitions and Economic Motivations ......................................3 2.2 Vulnerability and Defending the Regime for the Sake of Survival ..................3 2.3 The Alawite Dilemma ..................................................6 2.4 Regime Militias .......................................................8 2.5 From Popular Committees to Paramilitaries ..................................9 2.6 Shabiha Organization ..................................................9 2.7 Shabiha Talk ........................................................10 2.8 The -

POLS 3960: U.S. Strategy in Asia, Spring 2016 Syllabus (PDF)

POLS 3960 U.S. Strategy in Asia Spring 2016, MWF 12:00-12:50 Classroom: Brouster Hall 040 Professor Nori Katagiri Email: [email protected] Office: McGannon 127 Phone: 977-3044 Office hours: MW 1400-1500 or by appointment Course Description and Objectives: This course is designed to explore various parts of East Asia and American strategy to deal with issues we face in the region. The countries we examine primarily include those in Northeast Asia, China, and Southeast Asia. We will discuss the nature of relationship the United States maintains with countries in East Asia and our strategic options mostly in the post-Cold War era. In so doing, we will explore what political ends the country has in Asia and what strategy there is to pursue them. In this course, we seek to explore the past, present, and future of East Asian politics, economy, and security gain familiarity with the theoretical literature on US interests in East Asia analyze the nature of US relationship with East Asia understand the role of power, resources, and ideas in the formation and application of national and regional interests investigate a set of strategic options for the United States, and hone critical thinking on political events taking place in East Asia The course is divided into four sections: (1) the past and present (2) American strategy, (3) Northeast Asia and China, and (4) Southeast and South Asia. First, we examine the background of our interests in the region. Second, we explore our strategic choices in East Asia. Third, we discuss strategic options we have in China and Northeast Asia. -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020 KurdishLegitimacy Political and and Citizenship Civil Movements in inthe Syria Arab World This publication is also available in Arabic under the title: ُ ف الحركات السياسية والمدنية الكردية ي� سوريا وإشكالية التمثيل This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. For questions and communication please email: [email protected] Cover photo: A group of Syrian Kurds celebrate Newroz 2007 in Afrin, source: www.tirejafrin.com The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and the LSE Conflict Research Programme should be credited, with the name and date of the publication. All rights reserved © LSE 2020. About Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World is a project within the Civil Society and Conflict Research Unit at the London School of Economics. The project looks into the gap in understanding legitimacy between external policy-makers, who are more likely to hold a procedural notion of legitimacy, and local citizens who have a more substantive conception, based on their lived experiences. Moreover, external policymakers often assume that conflicts in the Arab world are caused by deep- seated divisions usually expressed in terms of exclusive identities. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

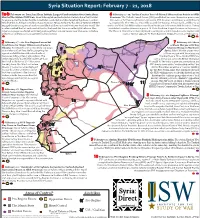

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

Uitgelokte Aanval Op Haar Burgers.S Wij Roepen Alle Democratische

STOP TURKIJE'S OORLOG TEGEN DE KOERDEN De luchtaanvallen van Turkije hebben Afrin geraakt, een Koerdische stad in Noord-Syrie, waarbij verschillende burgers zijn gedood en verwondNiet alleen de Koerden, maar ook christenen, Arabieren en alle andere entiteiten in Afrin liggen onder zware aanvallen van TurkijeDe agressie van Turkije tegen de bewoners van Afrin is een overduidelijke misdaad tegen de mensheid; het is niet anders dan de misdaden gepleegd door ISIS. Het initiëren van een militaire aanval op een land die jou niet heeft aangevallen is een oorlogsmisdaad. Turkse jets hebben 100 plekken in Afrin als doelwit genomen, inclusief vele civiele gebieden. Ten minste 6 burgers zijn gedood en I YPG (Volksbeschermingseenheden) en 2 YPJ (Vrouwelijke Volksbeschermingseenheden) -strijders zijn gemarteld tijdens de Turkse aanvallen van afgelopen zaterdag. Ook zijn als gevolg van de aanval een aantal burgers gewond geraakt.Het binnenvallende Turkse leger voerde zaterdagmiddag omstreeks 16:00 uur luchtaanvallen uit op Afrin met de goedkeuring van Rusland. De aanvallen die door 72 straaljagers werden uitgevoerd raakten het centrum van Afrin, de districten Cindirêsê, Reco, Shera, Shêrawa en Mabeta. Ook werd het vluchtelingenkamp Rubar geraakt. Het kamp wordt bewoond door meer dan 20.000 vluchtelingen uit Syrië. Het bezettende Turkse leger en zijn terroristen probeerden eerst middels aanvallen via de grond Afrin binnen te dringen, maar zij faalden. Daarom probeerden ze de bewoners van Afrin bang te maken en ze te verdringen naar vrije gebieden van het Syrische leger / gebieden die door Turkije worden beheerd. Het inmiddels zeven jaar durende interne conflict in Syrië is veranderd in een internationale oorlog.