A Presentation of Partners in Torah & the Kohelet Foundation MENTOR NOTE: Our Primary Goal in This Session Is to Introduce Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Female Figures in Tanach April 2, 2020 Sources

Female Figures in Tanach April 2, 2020 Sources Miriam A. Megillah 14a:14-15 Miriam was a prophetess, as it is written explicitly: “And Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took a timbrel in her hand” (Exodus 15:20). The Gemara asks: Was she the sister only of Aaron, and not the sister of Moses? Why does the verse mention only one of her brothers? Rav Naḥman said that Rav said: For she prophesied when she was the sister of Aaron, i.e., she prophesied since her youth, even before Moses was born, and she would say: My mother is destined to bear a son who will deliver the Jewish people to salvation. And at the time when Moses was born the entire house was filled with light, and her father stood and kissed her on the head, and said to her: My daughter, your prophecy has been fulfilled. But once Moses was cast into the river, her father arose and rapped her on the head, saying to her: My daughter, where is your prophecy now, as it looked as though the young Moses would soon meet his end. This is the meaning of that which is written with regard to Miriam’s watching Moses in the river: “And his sister stood at a distance to know what would be done to him” (Exodus 2:4), i.e., to know what would be with the end of her prophecy, as she had prophesied that her brother was destined to be the savior of the Jewish people. B. Excerpted from Chabad.org: Miriam's Well: Unravelling the Mystery, By Yehuda Shurpin Toward the end of the Israelites’ sojourn in the desert, the verse tells us, “The entire congregation of the children of Israel arrived at the desert of Zin in the first month, and the people settled in Kadesh. -

Shabbos 109.Pub

א' תמוז תשפ“ Tues, Jun 23 2020 OVERVIEW of the Daf Gemara GEM 1) Health issues (cont.) Submerging and Soreness אבל לא בים הגדול The Gemara concludes its discussion of various health related issues. 2) Basting a roast R ambam (Hilchos Shabbos 21:29) writes that the Gemara lists Zeiri and Chiya bar Ashi disagreed whether it is permissible to specific bodies of water in which it is prohibited to bathe on Shab- baste a roast with oil and whisked eggs on Shabbos. bos. These bodies of water each have a specific issue related to it 3) Medical treatments which causes some ill-effect to a person who immerses in it. On the Mar Ukva rules: It is permitted to to use wine reduce the swell- one hand, the overall effect of these pursuits is one of comfort, and ing of an injury on Shabbos. Concerning the use of vinegar, R’ there is even a therapeutic benefit which results. Yet Shabbos is we must indulge in – וקראת לשבת עוג “ Hillel reported that it is forbidden. defined by the concept of Rava qualified Mar Ukva’s ruling and stated that in Mechuza aspects of physical enjoyment”. The very fact that the means to even the use of wine is prohibited due to their sensitive nature. achieve these goals is by experiencing some degree of pain, these 4) Bathing for therapeutic purposes measures are inherently prohibited on Shabbos. Details regarding bathing for therapeutic reasons are clarified. According to Rambam, the reason we cannot bathe in these 5) MISHNAH: Consuming food for therapeutic reasons is dis- waters is not necessarily due to the rabbinic restrictions against us- cussed with a number of examples. -

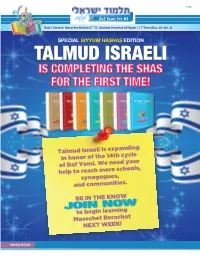

Talmud Israeli Is Completing the Shas for the First Time!

בס"ד Daf Yomi For US Seder Taharot | Masechet Niddah 67-73 | Shabbat Parashat VaYigash | 1-7 Tevet (Dec. 29-Jan. 4) TALMUD ISRAELI IS COMPLETING THE SHAS FOR THE FIRST TIME! Talmud Israeli is expanding in honor of the 14th cycle of Daf Yomi. We need your help to reach more schools, synagogues, and communities. BE IN THE KNOW to begin learning Masechet Berachot NEXT WEEK! Weekly Kit 324 Seder Taharot | Niddah 67-68 Mar Ukva MILESTONES IN – מַ ר ּעוקְ בָ א :Daf 67 JEWISH HISTORY Mar Ukva lived during the first Amoraic generation and was a contemporary of Rav and Shmuel. LAUNCH OF DAF YOMI Mar Ukva was an Amora, an exceptional Torah scholar, and served as the Reish Galuta (Exilarch, On the first day of the month of Tishrei, or leader of the Babylonian Jewish community). the first day of Rosh Hashanah, in 1923, Mar Ukva came from Kafri, the same city as the worldwide Daf Yomi cycle began with Rav, seat of a renowned Beit Din (court), whose thousands of Jewish people around the power of judgement was considered supreme world learning Masechet Berachot. in the eyes of sages throughout Babylonia. On When the First World Congress of the World many occasions, the Beit Din in Kafri was chosen Agudath Israel took place in Vienna a month to provide the final determination in halachic earlier, Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who became the deliberations between two gedolim (expert Torah rosh yeshiva of Yeshivas Chochmei Lublin scholars) such as Shmuel and Karna. in Poland, announced his innovative idea to initiate a new type of learning. -

Daf 16 August 27, 2014

1 Elul 5774 Moed Katan Daf 16 August 27, 2014 Daf Notes is currently being dedicated to the neshamah of Tzvi Gershon Ben Yoel (Harvey Felsen) o”h May the studying of the Daf Notes be a zechus for his neshamah and may his soul find peace in Gan Eden and be bound up in the Bond of life The Gemora cites Scriptural sources for the following excommunication (after thirty days) and place him in halachos: It is proper practice to send an emissary cheirem (after sixty days) if he still refuses to abide from the court and summon the defendant to appear by the Beis Din’s instructions. Rav Chisda says that before the Beis Din; we compel the defendant to we warn him on Monday (and place him immediately come before Beis Din (and not that the Beis Din goes under a ban); we warn him again on Thursday (and if to him); we notify the defendant that the judge is a he is still does not repent, we excommunicate him great man; we notify the defendant that so-and-so again); and the following Monday we place him in the plaintiff will be appearing in the Beis Din; we set cheirem. The Gemora notes that Rav chisda’s ruling a precise date to appear in Beis Din; we establish is for monetary matters, but if he shows contempt another date if the defendant does not come to Beis (to the Torah or to scholars), we excommunicate him Din the first time he was called; the agent of the Beis immediately (without any warning). -

Parshat Pinchas 5779

Dedicated in memory of Rachel Leah bat R' Chaim Tzvi Volume 11 Number 22 Brought to you by Naaleh.com Practical Bitachon- Part III Based on a Naaleh.com shiur by Rebbetzin Leah Kohn Chazal say that before Adam sinned, not only Nothing happens without his decree. This is The first level is the level of tzadikim. Yonatan did he not have to work for his bread, but the how we reveal Hashem from within the took a boy with him to the Midianite camp. He angels served it to him on a silver platter. It hiddenness. It’s a difficult test because the fought the Midianites and won the war. It was was obvious to Adam that everything came external and the internal seem to contradict an open miracle. Does this mean we can do from Hashem. After the sin, the situation each other. I’m investing so much effort and things that according to nature would never changed. Adam was cursed that he would time and I have to believe it’s not what is work? It depends on one’s level. Rabi Avraham have to work. In fact, Chazal say there were bringing me sustenance, it’s Hashem. says that people who did this felt the spirit of eleven processes Adam had to do before he Hashem inside them. They felt an urge and a could obtain bread. This idea of having to The Chazon Ish gives an example of what it strength that made them capable of fulfilling work to subsist is unique to humanity. All other means to really live bitachon. -

A Fence Around the Torah

18 Nissan 5773 Eiruvin Daf 21 March 29, 2013 Daf Notes is currently being dedicated to the neshamah of Tzvi Gershon Ben Yoel (Harvey Felsen) o”h May the studying of the Daf Notes be a zechus for his neshamah and may his soul find peace in Gan Eden and be bound up in the Bond of life The Chachamim only allowed one to use the boards of the well for the animals of the Jewish pilgrims on the The Gemora wonders: “What was the use?” you ask; festivals. surely it is to enable people to draw water from the wells!? Rabbi Yitzchak bar Adda said: The Chachamim only permitted people to enclose the area of the well with The Gemora explains Rav Anan’s question: Of what use is boards for the use of the Jewish pilgrims who would it that the head and the greater part of the body of the come to Jerusalem for the festivals and needed to draw cow is within the enclosure? [If he is merely placing the water. This means that the permit was for the animals of bucket down before the animal, why is it necessary to for the pilgrims, but if a person wished to drink from the the animal to be inside the enclosure?] well, he would have to climb into the well and drink inside the well. And although Rav Yitzchak said in the Abaye explained: Here we are dealing with a trough that name of Rav Yehudah, who said in the name of Shmuel stands in a public domain, and one that is ten tefachim that the boards for the well are only permitted for a well high and four tefachim wide (making it into a private that contains spring-water which is a natural spring, and domain, one where it would be permitted to carry on top to an animal – it makes no difference if the well contains of it), and one of its sides projects into the area between running water or collected water, this only means that the pasei bira’os. -

Daf 108 June 22, 2020

30 Sivan 5780 Shabbos Daf 108 June 22, 2020 Daf Notes is currently being dedicated to the neshamot of Moshe Raphael ben Yehoshua (Morris Stadtmauer) o”h Tzvi Gershon ben Yoel (Harvey Felsen) o”h May the studying of the Daf Notes be a zechus for their neshamot and may their souls find peace in Gan Eden and be bound up in the Bond of life Hides for Writing Tefillin Mar the son of Ravina asked Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak whether one may write tefillin on the skin of a kosher fish, Rav Huna says that one may write tefillin on the skin of a and he answered that we must wait for Eliyahu to come kosher species bird. and answer this. Rav Yosef asked what Rav Huna is teaching us, as we The Gemora explains that we know that a fish has skin, as already know that its skin is considered bona fide skin, we see it does, and the Mishna tells us that a fish’s bones since our Mishna says that one who wounds a bird on and skin can prevent things from becoming impure in a Shabbos is liable for the act of chovel – wounding. tent with a corpse. Rather, the question Eliyahu must answer for us is whether a fish’s skin is sufficiently clean Abaye answered that Rav Huna taught us a lot, as we still from the odor of the fish to be used as parchment for may have thought that one may not write on them since tefillin. they have holes. Rav Huna therefore had to teach us that it is still valid, as they ruled in Eretz Yisrael that any hole Shmuel and Karna were sitting at the bank of the Malka over which ink can pass is not considered a hole. -

MAASELER Moşavası, Ilk Aliya Dalgası Sırasında Oleler Toprak Işinde Usta Değildi Ve Bazı Kurulan Moşavaların Üçüncüsüydü

NİDA PEREK 1: ŞAMAY MASEHET NİDA PEREK 1: ŞAMAY Bet Şamay ve Bet İllel Yaprak Masehet Nida’nın ilk mişnasında, Şamay ve İllel’in şahısları arasında son derece ender görülen bir görüş ayrılığı yer almaktadır. Bizim genellikle bildiğimiz görüş ayrılıkları, bu iki büyük hahamın ekolleri olan Bet Şamay ve Bet İllel arasındadır; ama 2 burada şahsen Şamay ile Hillel görüş ayrılığı içindedir. “Dorot Yeşarim” adlı kitap, “Bet Şamay” ve “Bet İllel”in iki büyük yeşiva olduğunu yazar. Bu yeşivalar “Yeşivat Bet Şamay” ve “Yeşivat Bet İllel” adını taşırdı. Yeşivaların başında da Şamay ve İllel vardı. Bu yeşivalar nasıl kurulmuştu? Haşmonay hanedanına mensup iki kardeş olan Orkanus ve Aristobulus arasındaki çekişme döneminde, Orkanus tarafından kendisine yardım etmeleri için çağrılan Romalılar, Yisrael halkının üzerinde egemenlik kurmuşlar ve Sanedrin’i lağvetmişlerdi. Neslin liderliği, yani Nasi (başkan) mevkii, “Bene Betera”nın eline teslim edildi (Pesahim 66a; bkz. I. Kitap, sayfa 36) ve onlar da liderliği, İllel Babil’den Erets-Yisrael’e çıktığı zaman ona aktardılar. Ancak bu Nasi’lik, büyük Bet Din’in başkanlığı değil, bir tür yeşiva başkanlığı niteliğindeydi. Romalıların Sanedrin’in tekrar kurulduğundan şüphelenmelerine neden olarak onların gazabını uyandırmamak için, Şamay’ın başkanlığında bir bet midraş daha kuruldu. Bu şekilde, Romalıları şüpheye sürükleyecek tek bir büyük ve merkezi bet midraş olmayacaktı (“Dorot Rişonim”, II. ve III. Bölüm. “Vayar Menuha” kitabının I. bölümünde aktarılmaktadır. Ayrıca bkz. Rav Margaliyot’un, “Yesod A-Mişna VaArihata” adlı kitabı). Zihron Yaakov Hahamlarımızdan 1882 yılında Karmel Dağı’nın mahsulleri yetiştirmek için “Tetis” adlı bir güneyinde kurulan Zihron Yaakov gemiyle buraya geldi. Ancak yeni gelen MAASELER moşavası, ilk aliya dalgası sırasında oleler toprak işinde usta değildi ve bazı kurulan moşavaların üçüncüsüydü. -

Magyar Zsidó Lexikon

A Ab, 1. Av. működött. Apja könyvét adta ki toldalékokkal Abarjániiu (h.). Hitszegők, olyan zsidók, Modoó Zidto címmel (Zolkiew 1806). Munkái: akik a vallás törvényein, a rabbinikus törvényszék Chen Tóv, kommentár a kódexekhez (kiadta veje, (1. Bész-(lin) ítéletein és döntvényein tálteszik Frankéi Isaak és Zeved Tov c. toldalékokkal látta magukat. A hitközségi alapszabályok semmibe el, Zolkiew 1806), Imre Nóam, responsumok (Mun vevése szintén az A. közé való sorozást vonja kács 1885), Imre Joab. homiliák (Lemberg 1893). maga után. 1-iégebben egyházi átokkal és kiközö Megh. 1810. Utódja veje lett, akit később Nagy sítéssel büntették a hitszegőket, úgy hogy nem károlybahívtak meg. 1830-ban Lőw Eleázár (1. o.) vehettek részt a közös istentiszteleteken sem. Ezt a Seynen Bokeach szerzője került Liptószentmik- a súlyos büntetést az Engesztelő Ünnepen, jom- lósról A.-ra. A zsidók lélekszáma 1820-ban 1100, kippnrkor, felfüggesztették, de az ünnep elmúltá 1850.pedig 2900 volt. Lőw, aki nagy jesivát tartott val automatikusan megint életbelépett. A kiátko fenn, 1836. halt meg. Őt fiának veje: Lőw Benjá zás ós kiközösítés ma már csak a chásszidikus min (1. o.) a Saáré Tóra szerzője követte, majd irányú hitközségekben fordul elő, ott is elvétve Lipschütz Izsák Nátán került a rabbiszékbe, ki csupán, a modern hitközségek nem élnek ezzel a azelőtt Hegyalja-Mádon működött. 1869-ben, mint fegyverrel. A jomkippuri istentisztelet mindazon az orthodoxok képviselője, tiltakozott a bécsi kor által még ma is ezzel a mondattal kezdődik: «A mánynál a rabbi képző intézet felállítása ellen; menybéli törvényszék nevében, a földön ítélkező 1873. megh. 1830—40 között Horovitz Feivel bíróság nevében megengedjük, hogy együtt imád rabbihelyettes látta el a lelkészi funkciókat, ké kozhassunk a hitszegőkkel)). -

Bava Basra 151.Pub

כ"ח סיון תשעז“ Thursday, Jun 20 2017 א רא קנ“ בבא בת OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) Defining the intent of different phrases (cont.) The mother of Rami and Rav Ukva and her famous gifts אימיה דרמי בר חמא באורתא כתבתינהו לנכסה לרמי בר חמא The Gemara concludes its list of items included in the בצפרא כתבתינהו לרב עוקבא בר חמא . נכסים definition of the word The Gemara questions whether a Sefer Torah is includ- and the matter is left I n our Gemara, we find a story of the mother of Rami and נכסים ed in the definition of the term unresolved. Rav Ukva, the sons of Chamma. One evening, their moth- er wrote a gift of her property to Rami, and the next morn- 2) Sheltering money ing she wrote a different document presenting the same An incident involving a woman who attempted to shel- property to Rav Ukva. When each approached a judge to ter her possessions from her husband is recorded. allow him to take possession of the land, Rav Sheishes A second incident involving a woman sheltering her awarded the land to Rami, while Rav Nachman awarded the property is presented with the subsequent debate between property to Rav Ukva. R’ Nachman and R’ Sheishes. The Gemara in Kesubos (94b) relates a similar story about this family. There, one morning the mother wrote a 3) A sickbed gift document giving her possessions to Rami bar Chamma, Three incidents involving sickbed gifts are recounted. and in the evening she wrote a document giving the proper- R’ Nachman is cited as ruling that a deathly ill person’s ty to Mar Ukva. -

Ves, and Human Dignity Miriam Gedwiser ~ Drisha Fall 5780 V - Avoiding Shame: Tamar, R Eliezer, Imma Shalom

Husbands, Wives, and Human Dignity Miriam Gedwiser ~ Drisha Fall 5780 V - Avoiding Shame: Tamar, R Eliezer, Imma Shalom 1. Ketubot 67b מר עוקבא הוה עניא בשיבבותיה דהוה The Gemara recounts another incident related to רגיל כל יומא דשדי ליה ארבעה זוזי ,charity. Mar Ukva had a pauper in his neighborhood בצינורא דדשא יום אחד אמר איזיל איחזי and Mar Ukva was accustomed every day to toss מאן קעביד בי ההוא טיבותא ההוא יומא four dinars for him into the slot adjacent to the hinge נגהא ליה למר עוקבא לבי מדרשא אתיא of the door. One day the poor person said: I will go דביתהו בהדיה and see who is doing this service for me. That day Mar Ukva was delayed in the study hall, and his wife came with him to distribute the charity. כיון דחזיוה דקא מצלי ליה לדשא נפק When the people in the poor man’s house saw that בתרייהו רהוט מקמיה עיילי לההוא אתונא someone was turning the door, the pauper went out דהוה גרופה נורא הוה קא מיקליין כרעיה after them to see who it was. Mar Ukva and his wife דמר עוקבא אמרה ליה דביתהו שקול ran away from before him so that he would not כרעיך אותיב אכרעאי חלש דעתיה אמרה determine their identity, and they entered a certain ליה אנא שכיחנא בגויה דביתא ומקרבא furnace whose fire was already raked over and אהנייתי tempered but was still burning. Mar Ukva’s legs were being singed, and his wife said to him: Raise your legs and set them on my legs, which are not burned.