Auspicious Urbanisms: Security and Propaganda in Myanmar’S New Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President U Thein Sein Offers Religious Titles to Recipient Sayadaws, Offers Rice and Alms to Members of the Sangha

THENew MOST RELIABLE NEWSPAPER LightAROUND YOU of Myanmar Volume XX, Number 341 1st Waning of Tabaung 1374 ME Wednesday, 27 March, 2013 President U Thein Sein offers religious titles to recipient Sayadaws, offers rice and alms to members of the Sangha President U Thein Sein, Vice-Presidents Dr Sai Mauk Kham and U Nyan Tun and party attend religious titles presentation ceremony.—MNA N AY P YI T AW , 26 Hmon, Vice-President U Commander-in-Chief of Ward of Mahaaungmye Vice-Senior General Soe thavaçaka Pandita, Kam- March—President U Thein Nyan Tun and wife Daw Defence Services Com- Township and Sayadaw Win, U Nanda Kyaw mathanaçaria, Saddhama Sein presented religious Khin Aye Myint, Chief mander-in-Chief (Army) Bhaddanta Kesara of Maha Swa, General Hla Htay Jotikadhaja Ganthavaçaka titles to recipient Sayad- Justice of the Union U Tun Vice-Senior General Soe Aungmye Yeiktha Monas- Win, Union ministers, the Pandita, Kammathanaçari- aws and offered rice to Tun Oo, Daw Kyu Kyu Win and wife Daw Than tery in Hlinethaya Town- Auditor-General of the ya, Saddhamma Jotikad- members of the Sangha Hla, wife of Commander- Than Nwe, Deputy Speaker ship. Union, the commander of haja titles to recipient at Sasana Maha Beikman in-Chief of Defence Ser- of Pyithu Hluttaw U Nanda Vice-President U Nay Pyi Taw Command Sayadaws. in the precinct of Nay Pyi vices Senior General Min Kyaw Swa and wife, Chief Nyan Tun also offered and deputy ministers pre- Likewise, Daw Nan Taw Uppatasanti Pagoda Aung Hlaing, Chairman of the General Staff (Army, Abhidhaja Agga Maha sented Abhidhaja Agga Shwe Hmon and Daw this noon. -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

↓ Burma (Myanmar)

↓ Burma (Myanmar) Population: 51,000,000 Capital: Rangoon Political Rights: 7 Civil Liberties: 7 Status: Not Free Trend Arrow: Burma received a downward trend arrow due to the largest offensive against the ethnic Karen population in a decade and the displacement of thousands of Karen as a result of the attacks. Overview: Although the National Convention, tasked with drafting a new constitution as an ostensible first step toward democracy, was reconvened by the military regime in October 2006, it was boycotted by the main opposition parties and met amid a renewed crackdown on opposition groups. Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party, remained under house arrest in 2006, and the activities of the NLD were severely curtailed. Meanwhile, a wide range of human rights violations against political activists, journalists, civil society actors, and members of ethnic and religious minority groups continued unabated throughout the year. The military pressed ahead with its offensive against ethnic Karen rebels, displacing thousands of villagers and prompting numerous reports of human rights abuses. The campaign, the largest against the Karen since 1997, had been launched in November 2005. After occupation by the Japanese during World War II, Burma achieved independence from Great Britain in 1948. The military has ruled since 1962, when the army overthrew an elected government that had been buffeted by an economic crisis and a raft of ethnic insurgencies. During the next 26 years, General Ne Win’s military rule helped impoverish what had been one of Southeast Asia’s wealthiest countries. The present junta, led by General Than Shwe, dramatically asserted its power in 1988, when the army opened fire on peaceful, student-led, prodemocracy protesters, killing an estimated 3,000 people. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

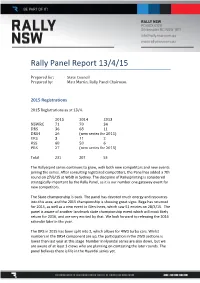

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

The India-Myanmar Relationship: New Directions After a Change of Governments?

Articles IQAS Vol. 48 / 2017 3–4, pp. 171–202 The India-Myanmar Relationship: New Directions after a Change of Governments? Pierre Gottschlich Abstract Despite a promising start after independence, bilateral relations between India and Myanmar have had a long history of mutual neglect and obliviousness. This paper revisits the develop- ments since the end of colonial rule and points out crucial historical landmarks. Further, the most important policy issues between the two nations are discussed. The focal point of the analysis is the question of whether one can expect new directions in the bilateral relationship since the election of new governments in India in 2014 and in Myanmar in 2015. While there have been signs of a new foreign policy approach towards its eastern neighbour on the part of India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it remains to be seen if the government of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy will substantially alter Myanmar’s course on an international level. Keywords: India, Myanmar, Burma, foreign policy, bilateral relations 1. Introduction Recent political developments in Myanmar1 have led to hopes for ground- breaking democratisation and liberalisation processes in the country (Bünte 2014; Kipgen 2016). In particular, the landslide victory of the former opposi- tional National League for Democracy (NLD) under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi in general elections in 2015, with the subsequent formation of an NLD government in early 2016, is seen as a turning point in the history of Myanmar. With a potentially major political and economic transformation, there might also be room for a reconsideration of Myanmar’s foreign policy, particularly with regard to its giant neighbours, China and India (Gordon 2014: 193–194). -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on the BBC’s Impartiality, Accountability and Integrity BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University International Anglophone Media Studies Laura Kaai 3617602 Simon Cook January 2013 7,771 Words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Framework 4 2.1 The BBC’s Values 4 2.1.2 Impartiality 5 2.1.3 Conflicts of Interest 5 2.1.4 Past Controversy: The Russell Brand Show and the Carol Thatcher Row 6 2.1.5 The Clarkson Controversy 7 2.2 Columns 10 2.3 Media Discourse Analysis 12 2.3.2 Agenda Setting, Decoding, Fairness and Fallacy 13 2.3.3 Bias and Defamation 14 2.3.4 Myth and Stereotype 14 2.3.5 Sensationalism 14 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 15 3.1.2 Procedure 16 3.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 17 3.2.2 Procedure 19 4. Discussion 21 4.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 21 4.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 23 5. Conclusion 26 Works Cited 29 Appendices 35 3 1. Introduction “I’d have them all shot in front of their families” (“Jeremy Clarkson One”). This is part of the comment Jeremy Clarkson made on the 2011 public sector strikes in the UK, and the part that led to the BBC receiving 32,000 complaints. Clarkson said this during the 30 December 2011 live episode of The One Show, causing one of the biggest BBC controversies. The most widely watched factual TV programme in the world, with audiences in 212 territories worldwide, is BBC’s Top Gear (TopGear.com). -

Japan-ASEAN Connectivity Initiative(PDF)

November. 2020 Japan-ASEAN Connectivity Initiative MOFA Japan has supported ASEAN's efforts to strengthen connectivity in order to narrow the gaps in the ASEAN region and further facilitate the integration of ASEAN community based on the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC) 2025 and Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) Masterplan. Japan will continue to provide support in this field. Japan has announced its decision to support strengthening ASEAN connectivity both in hard and soft ware with focus on the ongoing 2 trillion yen worth of land, sea, and air corridor connectivity infrastructure projects as below, together with capacity building projects for 1,000 individuals over the next three years. “Land Corridor” East-West Corridor *The following connectivity projects include projects (Thailand) The road connecting Da Nang, Viet Nam under consideration. (Cambodia) ・Mass Transit System Project and Mawlamyaing, Myanmar ・National Road No. 5 Improvement Project “Sea and Air corridor” in Bangkok (RED LINE) Southern Corridor ( ) (Myanmar) The road connecting Ho Chi Minh, Viet Nam Cambodia ・ ・Bago River Bridge Construction Project and Dawei, Myanmar Sihanoukville Port New Container Terminal Development Project ・East-West Economic Corridor Improvement Project Mandalay Hanoi ・ ・East-West Economic Corridor Highway Development The Project for Port EDI for Port Myanmar Modernization Project (Phase 2)(New Bago-Kyaikto Highway Section) Naypyidaw Laos (Myanmar) ・Infrastructure Development Project in Thilawa Area Phase -

The Brookings Institution

MYANMAR-2021/07/22 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION WEBINAR THE QUAGMIRE IN MYANMAR: HOW SHOULD THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY RESPOND? Washington, D.C. Thursday, July 22, 2021 PARTICIPANTS: JONATHAN STROMSETH Senior Fellow Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asian Studies, Foreign Policy The Brookings Institution AYE MIN THANT Features Editor Frontier Myanmar Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Formerly at Reuters MARY CALLAHAN Associate Professor Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington DEREK MITCHELL President National Democratic Institute for International Affairs Former U.S. Ambassador to Myanmar (Burma) KAVI CHONGKITTAVORN Senior Fellow Institute of Security and International Studies Chulalongkorn University’ Columnist Bangkok Post * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 MYANMAR-2021/07/22 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. STROMSETH: Greetings. I’m Jonathan Stromseth, the Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asian Studies at Brookings and I’m pleased to welcome everyone to this timely event, the quagmire in Myanmar: How should the international community respond? Early this year, the Burmese military also known as the Tatmadaw detained State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and other civilian leaders in a coup d’état ending a decade of quasi- democracy in the country. The junta has since killed hundreds of protestors and detained thousands of activists and politicians, but mass protests and mass civil disobedience activities continue unabated. In addition, a devasting humanitarian crisis has engulfed the country as people go hungry, the healthcare system has collapsed and COVID-19 has exploded adding a new sense of urgency as well as desperate calls for emergency assistance. -

7D Wonders of Myanmar 7D Wonders Of

31 buildings, the significance of 31 is said to DAY 6 refer to the 31 'planes of existence' in Buddhist cosmology. Today will be visiting gem museum YANGON - Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner - where Myanmar is known for its precious stones. Transfer to Myanmar’s largest city After breakfast, begin your tour by visiting Yangon. Tonight savour the international buffet Chauk Htat Gyi Pagoda. It is known in Yangon while enjoying the royal cultural show at for its enormous 65 meters long Reclining Karaweik Palace, located at the eastern shore Buddha image. Next visit Bogyoke Market of Kandawgyi Lake. (formerly known as Scott’s market, closed on Monday) it is one of the best for souvenir shopping paradise. In the evening scroll through Shwedagon Pagoda, famous worldwide – its golden stupa is the ‘Heart’ of Buddhism in Myanmar. The Pagoda is believed to be 2,500 years old, covered with hundreds of gold plates, and the top of the stupa is encrusted with 7,000 over diamonds and precious gems; the largest of which is a 72 carat diamond. DAY 7 YANGON ✈ SINGAPORE - Breakfast, Meal on Board - After breakfast, it’s time to bid farewell to Myanmar, if time permits enjoy last min shopping at leisure before you proceed to the airport for your flight back to Singapore. We hope you have had a memorable time with ASA Holidays. 7D WONDERS OF MYANMAR (NYT7) Bagan Archaeological Area. First, visit colourful DAY 1 Nyaung Oo Market it is a well-known local market HIGHLIGHTS SINGAPORE ✈ NAY PYI TAW where you can find nearly all Myanmar goods in its different sections.