A Year Later: Suppression Continues in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf 129.08 K

The Role of Climate and Culture on the Formation of Courtyards in Mosques Hossein Soltanzadeh* Associate Professor of Architecture, Faculty of Art and Architecture, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran Received: 23/05/2015; Accepted: 30/06/2015 Abstract The process regarding the formation of different mosque gardens and the elements that contribute to the respective process is the from the foci point of this paper. The significance of the topic lies in the fact that certain scholars have associated the courtyard in mosques with the concept of garden, and have not taken into account the elements that contribute to the development of various types of mosque courtyards. The theoretical findings of the research indicate that the conditions and instructions regarding the Jemaah [collective] prayers on one hand and the notion of exterior performance of the worshiping rites as a recommended religious precept paired with the cultural, environmental and natural factors on the other hand have had their share of founding the courtyards. This study employs the historical analytical approach since the samples are not contemporary. The dependant variables are culture and climate while the form of courtyard in the jame [congregational] mosque is the dependent variable. The statistical population includes the jame mosques from all over the Islamic world and the samples are picked selectively from among the population. The findings have demonstrated that the presence of courtyard is in part due to the nature of the prayers that are recommended to say in an open air, and in part because this is also favoured by the weather in most instances and on most days. -

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

The Quality of Light-Openings in the Iranian Brick Domes

31394 Soha Matoor et al./ Elixir His. Preser. 80 (2015) 31394-31401 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Historic Preservation Elixir His. Preser. 80 (2015) 31394-31401 The Quality of Light-Openings in the Iranian Brick Domes (with the Structural Approach) Soha Matoor, Amene Doroodgar and Mohammadjavad Mahdavinejad Faculty of Arts and Architecture, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Paying attention to light is considered as one of the most prominent features of Iranian Received: 26 October 2014; traditional architecture, which influenced most of its structural and conceptual patterns. The Received in revised form: construction of light-openings in the buildings such as masjids, bazaars, madrasas, and 28 February 2015; caravanserais, as the Iranian outstanding monuments, proves the point. The Iranian master- Accepted: 26 March 2015; mimars’ strategies to create the light-openings in the domes has been taken into consideration through this study. To this end, the light-openings’ exact location, according to Keywords the domes’ structural properties have been taken into analysis. Next, based on the foursome The light, classification of the domes, the research theoretical framework has been determined, and The light-opening, through applying the case-study and the combined research methods, the case-studies have The Iranian brick dome, been studied meticulously. According to the achieved results, the light-openings of the The dome’s structure. Iranian brick domes have been located at four distinguished areas, including: 1- the dome’s top, 2- the dome’s curve, 3- the dome’s shekargah and 4- the dome’s drum. -

Jcc Iran Bg Final

31ST ANNUAL HORACE MANN MODEL UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 22, 2016 JCC: IRAN IRANIAN HOSTAGE CRISIS JAMES CHANG & MEHR SURI GEORGE LOEWENSON CHAIR MODERATORS TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE SECRETARIAT 3 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 4 COMMITTEE BACKGROUND 5 COMMITTEE PROCEDURE 6 THE IRANIAN HOSTAGE CRISIS 9 OVERVIEW OF THE TOPIC 9 HISTORY 9 CURRENT SITUATION 14 POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS 17 QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER 18 POSITIONS 18 SOURCES 25 Horace Mann Model United Nations Conference 2 LETTER FROM THE SECRETARIAT Dahlia Krutkovich DEAR DELEGATES, Isabella Muti Henry Shapiro Secretaries-General Welcome to Horace Mann's 31st annual Model United Nations Daniel Frackman conference, HoMMUNC XXXI! Since 1985, HoMMUNC has Maya Klaris engaged the future leaders of the world in a day full of learning, Noah Shapiro Directors-General debate, and compromise. The conference brings together intellectually curious high school and middle school students to Charles Gay Zachary Gaynor contemplate and discuss serious global concerns. We are honored Ananya Kumar-Banarjee to have inherited the responsibility of preparing this event for Livia Mann over 1000 students that will participate in HoMMUNC XXXI. William Scherr Audrey Shapiro Benjamin Shapiro Regardless of your age or experience in Model UN, we challenge Senior Executive Board you to remain engaged in the discourse of your committees and Joshua Doolan truly involve yourself in the negotiation process. Each committee Jenna Freidus Samuel Harris is comprised of an eclectic group of delegates and will address Charles Hayman and important global concern. Take this opportunity to delve deep Valerie Maier Radhika Mehta into that problem: educate yourself think innovatively to create Evan Megibow the best solutions, and lead the committee to a resolution that Jada Yang Under-Secretaries- could better the world. -

2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005

Iran Page 1 of 20 Iran Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 The Islamic Republic of Iran [note 1] is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shi'a Muslim clergy dominate the key power structures. Article Four of the Constitution states that "All laws and regulations…shall be based on Islamic principles." Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty (Article Six) and the rule of the Supreme Jurisconsulate (Article Five). The unelected Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ali Khamene'i, dominates a tricameral division of power among legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Khamene'i directly controls the armed forces and exercises indirect control over the internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The executive branch was headed by President Mohammad Khatami, who won a second 4-year term in June 2001, with 77 percent of the popular vote in a multiparty election. The legislative branch featured a popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, Majlis, which develops and passes legislation, and an unelected 12-member Council of Guardians, which reviews all legislation passed by the Majlis for adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles and also has the duty of screening Majlis candidates for eligibility. Conservative candidates won a majority of seats in the February Seventh Majlis election that was widely perceived as neither free nor fair, due to the Council of Guardians' exclusion of thousands of qualified candidates. The 34-member Expediency Council is empowered to resolve legislative impasses between the Council of Guardians and the Majlis. -

Freedom of Expression and Assembly, Deteriorated in 2006

January 2007 Country Summary Iran Respect for basic human rights in Iran, especially freedom of expression and assembly, deteriorated in 2006. The government routinely tortures and mistreats detained dissidents, including through prolonged solitary confinement. The Judiciary, which is accountable to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, is responsible for many serious human rights violations. President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s cabinet is dominated by former intelligence and security officials, some of whom have been implicated in serious human rights violations, such as the assassination of dissident intellectuals. Under his administration, the Ministry of Information, which essentially performs intelligence functions, has substantially increased its surveillance of dissidents, civil society activists, and journalists. Freedom of Expression Iranian authorities systematically suppress freedom of expression and opinion by closing newspapers and imprisoning journalists and editors. The few independent dailies that remain heavily self-censor. Many writers and intellectuals have left the country, are in prison, or have ceased to be critical. In September 2006 the Ministry of Culture and Guidance closed the reformist daily, Shargh, and shut down two reformist journals, Nameh and Hafez. In October the Ministry shut down a new reformist daily, Roozgar, only three days after it started publication. During the year the Ministry of Information summoned and interrogated dozens of journalists critical of the government. In 2006 the authorities also targeted websites and internet journalists in an effort to prevent online dissemination of news and information. The government systematically blocks websites inside Iran and abroad that carry political news and analysis. In September 2006 Esmail Radkani, director-general of the government- controlled Information Technology Company, announced that his company is blocking access to 10 million “unauthorized” websites on orders from the Judiciary and other authorities. -

The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC: a Major Iranian Intelligence Apparatus Dr

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) רמה כרמ כ ז ז מל מה ו י תשר עד מל מה ו ד ו י ד ע י י ע ן י ן ו רטל ( למ ו מ" ר ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC: A Major Iranian Intelligence Apparatus Dr. Raz Zimmt November 5, 2020 Main Argument The Intelligence Organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) has become a major intelligence apparatus of the Islamic Republic, having increased its influence and broadened its authorities. Iran’s intelligence apparatus, similar to other control and governance apparatuses in the Islamic Republic, is characterized by power plays, rivalries and redundancy. The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC, which answers to the supreme leader, operates alongside the Ministry of Intelligence, which was established in 1984 and answers to the president. The redundancy and overlap in the authorities of the Ministry of Intelligence and the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization have created disagreements and competition over prestige between the two bodies. In recent years, senior regime officials and officials within the two organizations have attempted to downplay the extent of disagreements between the organizations, and strove to present to domestic and foreign audience a visage of unity. The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization (ILNA, July 16, 2020) The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization, in its current form, was established in 2009. The Organization’s origin is in the Intelligence Unit of the IRGC, established shortly after the Islamic Revolution (1979). -

Recognition of Light-Openings in Iranian Mosques' Domes with Reference to Climatic Properties

International Journal of Architectural Engineering & Urban Planning Recognition of light-openings in Iranian mosques’ domes With reference to climatic properties Mohammadjavad Mahdavinejad1,*, Soha Matoor2, Amene Doroodgar3 Received:June 2011, Accepted: November 2011 Abstract Mosque architecture is considered as a potent visual symbol of the Islamic architects’ design ability. Prayer-hall as the manifestation of equality between the believers and the unity of architectural space has challenged such an ability throughout the history. This study, considering the characteristics of light-openings in the domes of Iranian mosques’ Prayer-hall, aims to investigate these domes’ possible relationship with the climatic features of each mosque. To this end, eighteen case-studies according to the research analytic approach are studied to determine: 1. the relationship between the mosques construction period (Iranian architecture styles) and its light-openings number on the one hand and its climatic features on the other hand, 2. The relationship between the light-openings’ location and the climatic features of each mosque, 3. The relationship between the light- openings’ number and the climatic feature of each mosque and finally, 4. The relationship between the prayer-hall’s height and the number of light openings of each mosque on the one hand and its climatic feature on the other hand. The study shows that Iranian architects have given considerable priority to the natural ventilation function of the light-openings, So, what used to be considered as the domes' main function, allowing the light to the interior space, is considered as their secondary function. Keywords: Light-opening, Light, Natural ventilation, Hot-dry climate, Cold climate, Mosque prayer-hall 1. -

Major General Hossein Salami: Commander-In-Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps October 2020

Major General Hossein Salami: Commander-in-Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps October 2020 1 Table of Contents Salami’s Early Years and the Iran-Iraq War ................................................................................................... 3 Salami’s Path to Power ................................................................................................................................. 4 Commander of the IRGC’s Air Force and Deputy Commander-in-Chief ....................................................... 5 Commander-in-Chief of the IRGC.................................................................................................................. 9 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 11 2 Major General Hossein Salami Major General Hossein Salami has risen through the ranks of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) since its inception after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. He served on the battlefield during the Iran-Iraq War, spent part of his career in the IRGC’s academic establishment, commanded its Air Force, served as its second-in-command, and finally was promoted to the top position as commander-in-chief in 2019. Salami, in addition to being an IRGC insider, is known for his speeches, which are full of fire and fury. It’s this bellicosity coupled with his devotion to Iran’s supreme leader that has fueled his rise. Salami’s Early Years and the Iran-Iraq War Hossein -

Perspectives on the 2009 Iranian Election

The anatomy of a crisis Perspectives on the 2009 Iranian election Issue 1, 2009 1 Created in November 2007 by students from the UK universities of Oxford, Leicester and Aberystwyth, e-International Relations (e-IR) is a hub of information and analysis on some of the key is- sues in international politics. As well as editorials contributed by students, leading academics and policy-makers, the website contains essays, diverse perspectives on global news, lecture podcasts, blogs written by some of the world’s top professors and the very latest jobs from academia, politics and international development. The pieces in this collection were published on e-International Relations during June 2009. Front page image by Hamed Saber edited and compiled by Stephen McGlinchey and Adam Groves 2 Contents 4 Introductory Notes 5 Iran’s Contested Election 10 Losing the battle for global opinion 12 Reading into Iran’s Quantum of Solace 14 Decisions Iranians should make and others should support 16 Why Iranians have to find their own course 18 The Iranian women’s rights movement and the election crisis 20 Defending the Revolution: human rights in post-election Iran 23 The 2009 Iranian elections: a nuclear timebomb? 26 Contributors 3 Introductory notes Stephen McGlinchey With the contested re-election of Mahmoud intensify Israeli fears that some kind of interven- Ahmadinejad on June 12th 2009 and the wide- tion was necessary for its own national security. spread protests that followed, domestic Iranian politics once again came to the fore internation- If reports are correct that the popular tide is ally. Not since the final days of the Shah, the turning against the regime in Iran, there is a Islamic revolution of 1979 and the ensuing hos- real danger that it will respond by pandering to tage crisis, had it occupied such a prime posi- populist fears in the country and enhancing its tion across the international political landscape. -

Two-Level Patterns in Practice

Persian Two-Level Patterns in Practice. Tony Lee, February/March 2016 Two-level patterns arise when the spaces between the lines of one pattern (the larger, or upper-level pattern) are filled with tiles of another pattern (the smaller or lower-level pattern). Usually the tiles of the lower-level pattern are so arranged that the pattern is continuous across the lines of the upper-level pattern. That is, in such a case, if the lines of the larger pattern were removed the smaller pattern would present a single, complex pattern covering the whole pattern area. If the upper and lower level patterns are similar, or contain the same shapes (but at two different scales) then such a pattern may be regarded loosely as self-similar. Most discussions of these concepts are concerned with Islamic geometric patterns, where there is frequently a large-scale pattern picked out in various ways ⏤ for example, by colour contrast, or greater width of banding ⏤ superimposed on a small-scale pattern. Strict self-similarity is rarely achieved in traditonal Islamic patterns. Recent literature on Islamic patterns has recognised a number of different categories of two-level patterns, but there is one category of tile mosaic in which the manner of execution has been consistently misrepresented in the computer graphic illustrations accompanying a number of modern accounts. In this type of two-level pattern the lines of the large or level-one pattern are widened as bands, separating different areas (polygons, compartments) of this upper level pattern, which are then filled with modular arrangements of parts of the smaller or level-two pattern. -

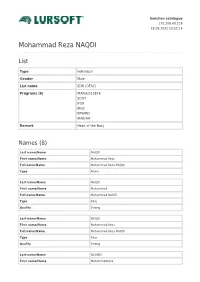

Mohammad Reza NAQDI

Sanction catalogue 170.106.40.219 28.09.2021 10:32:18 Mohammad Reza NAQDI List Type Individual Gender Male List name SDN (OFAC) Programs (6) IRAN-EO13876 SDGT IFSR IRGC NPWMD IRAN-HR Remark Head of the Basij Names (8) Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Mohammad Reza Full name/Name Mohammad Reza NAQDI Type Name Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Muhammad Full name/Name Muhammad NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Mohammad-Reza Full name/Name Mohammad-Reza NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAGHDI First name/Name Mohammedreza Full name/Name Mohammedreza NAGHDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Gholamreza Full name/Name Gholamreza NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAQDI First name/Name Gholam-reza Full name/Name Gholam-reza NAQDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name NAGHDI First name/Name Mohammad Reza Full name/Name Mohammad Reza NAGHDI Type Alias Quality Strong Last name/Name SHAMS First name/Name Mohammad Reza Full name/Name Mohammad Reza SHAMS Type Alias Quality Strong Citizenships (1) Country Iran Addresses (1) Country Iran Full address Iran Birth data (6) Birthdate Apr 1961 Birthdate 1951 to 1953 Birthdate 1960 to 1962 Place Tehran, Iran Country Iran Birthdate 1953 Place Najaf, Iraq Country Iraq Identification documents (1) Type Additional Sanctions Information -: Subject to Secondary Sanctions Updated: 28.09.2021. 05:15 The Sanction catalog includes Latvian, United Nations, European Union, United Kingdom and Office of Foreign Assets Control subjects included in sanction list.