MA Dissertation the Use of English and German Pattern Books at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

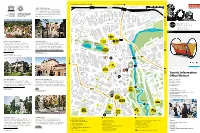

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

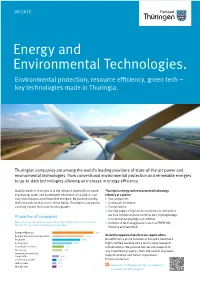

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

The Napoleon Series

The Napoleon Series Officers of the Anhalt Duchies who Fought in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1789-1815: Anhalt, Friedrich von By Daniel Clarke Friedrich von Anhalt was born on May 21, 1732, in Kleckewitz (Raguhn-Jeßnitz), in the Principality of Anhalt-Dessau. He was the brother of Albrecht von Anhalt (1735-1802) and the son of Wilhelm Gustav, Hereditary Prince of Anhalt-Dessau and Johanne Sophie Herre. He was unmarried. In June 1747 Friedrich entered the service of Prussia with the rank of Lieutenant in the 10th Infantry Regiment, von Anhalt-Dessau. The Chef of this regiment was Dietrich, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau, his uncle and younger brother of his father, who made Friedrich his Adjutant-General. Later, in 1749, another of his uncles, Leopold II, Prince of Anhalt- Dessau, made him his Adjutant, but when he died in 1751, Friedrich II, King of Prussia decided to take Friedrich on to his staff. In January 1752 Friedrich was promoted to Staff Captain in the Leibgarde Battalion of the 15th Infantry Regiment, Friedrich II of Prussia. Fighting in the Seven Years’ War, he was promoted to Staff Major in February 1757 and served Augustus Ferdinand, Prince of Prussia (1730-1813) as a staff officer at the Battle of Prague on May 6 that year. Switching from his staff position to the line during May 1757, Friedrich took command of a Grenadier Battalion in time for the Battle of Kolin (Kolín) on June 18. But, at the Battle of Moys (Zgorzelec) on September 7, Friedrich was badly wounded in an arm and captured by the Austrians, along with the whole Prussian force engaged that day. -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

Curriculum Vitae Germany

Historisches Institut Dr. Alexander Schmidt Akademischer Rat Universität Jena · Einrichtung · 07737 Jena Fürstengraben 13 07743 Jena Curriculum Vitae Germany Telefon: +49 36 41 9-4979 Telefax: +49 36 41 9-310 02 E-Mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC DEGREES Jena, 29. Februar 2020 M.A. (1,0, 2001, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena), Dr.phil. (summa cum laude, 2005, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena) ACADEMIC POSITION Akademischer Rat, Historisches Institut, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena PREVIOUS POSITIONS 07/2009-03/2017 Juniorprofessor of Intellectual History, Research Centre “Laboratory Enlightenment”, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena 10/2004-12/2008 Research fellow at the Collaborative Research Centre 482 “The Weimar-Jena phenomenon: Culture around 1800” (Sonderforschungsbereich 482 “Ereignis Weimar-Jena. Kultur um 1800”), Friedrich Schiller University of Jena 7/2001–1/2002 Research fellow at the Department of History (Early Modern Studies), Friedrich Schiller University of Jena GRANTS, AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS 7/2018 (together with Professor Paul Cheney, University of Chicago) Summer Institute for University and College Teachers sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities ($ 110,694), Visiting Faculty at University of Chicago 12/2017 Initial grant by the Centre for the Study of the Global Condition (Leipzig) for the “Human rights without religion?” project (5500 €) 7/2015-11/2016 Feodor-Lynen-Fellowship for Experienced Researchers (offered by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation) at the John U. -

August 2018 Texas Master Gardener Newsletter President's Message

August 2018 Texas Master Gardener Newsletter President's Message 2019 TMGA Conference Happy August! I heard last night on the news that my neighborhood near Houston has had temperatures above 95 degrees for 24 days straight! Many counties in our state are experiencing significant drought once again. While I was able to go to Canada for a reprieve from the heat, our gardens have not Victoria Master Gardeners are excited about the upcoming 2019 been as fortunate. As trained Master Gardeners, however, we are cognizant of conference. At the Directors Meeting, Victoria MG representatives providing proper plant selection, soil preparation, mulching, water conservation, etc. reported that the City of Victoria is eager to have Master Gardeners next to give our gardens the best possible chance of surviving. If we follow these proven April. In fact, they think this may be the biggest single group of visitors principles, the likelihood is good that our landscapes will make it through these tough that Victoria has ever experienced! Several great speakers and tours are times. As far as how the heat affects us as humans, well, that’s something different already being finalized. The website for the conference is “up,” but altogether! registration and details are planned to be ready on the website around September 1. Bookmark and visit the website frequently to watch for Stay cool and remember that everything changes in time! Autumn comes each year more details and registration. without fail! April 25-27 (Leadership Seminar, April 24) Nicky Maddams Pyramid Island Lake “Victoria – Nature’s Gateway” 2018 TMGA President Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada Victoria Community Center, 2905 E. -

Holy Roman Empire

WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 1 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 CONTENT Historical Background Bohemian-Palatine War (1618–1623) Danish intervention (1625–1629) Swedish intervention (1630–1635) French intervention (1635 –1648) Peace of Westphalia SPECIAL RULES DEPLOYMENT Belligerents Commanders ARMY LISTS Baden Bohemia Brandenburg-Prussia Brunswick-Lüneburg Catholic League Croatia Denmark-Norway (1625-9) Denmark-Norway (1643-45) Electorate of the Palatinate (Kurpfalz) England France Hessen-Kassel Holy Roman Empire Hungarian Anti-Habsburg Rebels Hungary & Transylvania Ottoman Empire Polish-Lithuanian (1618-31) Later Polish (1632 -48) Protestant Mercenary (1618-26) Saxony Scotland Spain Sweden (1618 -29) Sweden (1630 -48) United Provinces Zaporozhian Cossacks BATTLES ORDERS OF BATTLE MISCELLANEOUS Community Manufacturers Thanks Books Many thanks to Siegfried Bajohr and the Kurpfalz Feldherren for the pictures of painted figures. You can see them and much more here: http://www.kurpfalz-feldherren.de/ Also thanks to the members of the Grimsby Wargames club for the pictures of painted figures. Homepage with a nice gallery this : http://grimsbywargamessociety.webs.com/ 2 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 3 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 The rulers of the nations neighboring the Holy Roman Empire HISTORICAL BACKGROUND also contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War: Spain was interested in the German states because it held the territories of the Spanish Netherlands on the western border of the Empire and states within Italy which were connected by land through the Spanish Road. The Dutch revolted against the Spanish domination during the 1560s, leading to a protracted war of independence that led to a truce only in 1609. -

Lehigh County Potato Region

Agricultural Resources of Pennsylvania, c 1700-1960 Lehigh County Potatoes Historic Agricultural Region, 1850-1960 2 Lehigh County Potatoes Historic Agricultural Region, 1850-1960 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Location ......................................................................................................................... 8 Climate, Soils, and Topography .................................................................................... 9 Historical Farming Systems ........................................................................................... 9 1850-1910: Potatoes as One Component of a Diversified Farming System ................................................................................................. 9 1910-1960: Potatoes as a Primary Cash Crop with Diversified Complements .....................................................................................................30 Property Types and Registration Requirements – Criterion A, Pennsylvania......................................................................................... 78 Property Types and Registration Requirements – Criterion A, Lehigh County Potatoes Historic Agricultural Region, 1850-1960 ............................................................................... 82 Property Types and Registration Requirements – Criterion B, C, and D ............................................................................................... -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

71-7579 THIRY, Jr., Alexander George, 1930- REGENCY OF ARCHDUKE FERDINAND, 1521-1531; FIRST HABSBURG ATTEMPT AT CENTRALIZED CONTROL OF GERMANY, The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 History, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED REGENCY OF ARCHDUKE FERDINAND, 1521-1531: FIRST HABSBURG ATTEMPT AT CENTRALIZED CONTROL OF GERMANY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Alexander G. Thiry, B. A., M. A. ****** The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by Iviser Department of History PREFACE For those with professional interest in the Reforma tion era, Ferdinand of the House of Habsburg requires no special introduction here. As the younger and sole brother of Charles V, who was the Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation in the first-half of the sixteenth century, Ferdi nand's place among the list of secular, notables of the pe riod is assured. Singled out in 1521 by his imperial brother to be the Archduke of Austria and to become his personal representative in Germany, attaining the kingships of Bohe mia and Hungary in 1526 and 1527 respectively, and designated, following his brother's abdication and retirement from pub lic life in 1556, to succeed him as emperor of Germany, Fer dinand could not help leaving behind him from such political heights indelible footprints upon the course of history. Yet, probably because of the fragmentation of Ferdi nand's energy into these many various channels of responsi bility and the presence of his illustrious brother, Charles V, and his fanatical nephew, Philip II of Spain, who both eclipsed his own place on the stage of history, Ferdinand's historical significance has been largely overlooked by IX posterity. -

The Historical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Theses Theses and Dissertations 5-15-2010 The iH storical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach Marva J. Watson Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Watson, Marva J., "The iH storical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach" (2010). Theses. Paper 157. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Marva Jean Watson B.M., Southern Illinois University, 1980 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Degree School of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2010 THESIS APPROVAL THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH By Marva Jean Watson A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music History and Literature Approved by: Dr. Melissa Mackey, Chair Dr. Pamela Stover Dr. Douglas Worthen Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 2, 2010 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF MARVA JEAN WATSON, for the Master of Music degree in Music History and Literature, presented on 2 April 2010, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

News from the Office

Hyphen 67 News from the Office Office International du Coin de Terre et des Jardins Familiaux association sans but lucratif | June 2019 Hyphen 67 | 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents: Leading article The French allotment gardens throughout history 3 Introduction Added value allotment gardening: creating more environmental justice 5 Some examples The Netherlands: The allotment garden site Hoge Weide in Utrecht (NL), a unique site, an element for more environmental justice 8 Belgium: Ecological gardening: An added value for allotment gardeners, neighbourhood, fauna and flora 10 France: Vegetable gardens like no others 12 Great-Britain: The allotments in the United Kingdom, an element for environmental justice 14 Norway: Etterstad allotment garden, a gem for all in the middle of the town 16 Germany: The German allotment gardeners resolutely work for more environmental justice 18 Austria: Socially motivated support services by the central federation of allotment gardeners in Austria 22 Addresses 24 Impressum 25 Hyphen 67 | 2019 2 LEADING ARTICLE The French allotment gardens throughout history Daniel CAZANOVE Vice-president of the French allotment and collective garden federation Very sensitive to all the social prob- Etienne under the leadership of Father lems of his time, father LEMIRE cre- Félix VOLPETTE. ated the allotments in Hazebrouck (city in the north of France) in 1896 In 1928, France had 383,000 allotment and then founded the French “ligue du gardens, 70,000 of which were culti- coin de terre et du foyer” (allotment vated by railwaymen on land put at federation). their disposal by the railway society. Starting with this new period, the pro- The purpose of this ecclesiastic was file of the gardeners began to change to provide the head of the family with with the arrival of new socio-profes- a piece of land, both to grow the vege- sional categories: employees, trades- tables necessary for home consump- men, craftsmen ..