Dactyla Carnivora Chiroptera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAMMALS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE Below Are Some Helpful Symbols for Quick Comparisons and Identfication

MAMMALS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Below are some helpful symbols for quick comparisons and identfication. They are located in the same place for each species throughout this publication. Definitions for About this Book the scientific terms used in this publication can be found at the end in the glossary. Activity Method of Feeding Diurnal • Most active during the day Carnivore • Feeds primarily on meat Nocturnal • Most active at night Herbivore • Feeds primarily on plants Crepuscular • Most active at dawn and dusk Insectivore • Feeds primarily on insects A word about diurnal and nocturnal classifications. Omnivore • Feeds on both plants and meat In nature, it is virtually impossible to apply hard and fast categories. There can be a large amount of overlap among species, and for individuals within species, in terms of daily and/or seasonal behavior habits. It is possible for the activity patterns of mammals to change due to variations in weather, food availability or human disturbances. The Raccoon designation of diurnal or nocturnal represent the description Gray or black in color with a pale most common activity patterns of each species. gray underneath. The black mask is rimmed on top and bottom with CARNIVORA white. The raccoon’s tail has four to six black or dark brown rings. habitat Raccoons live in wooded areas with Tracks & Skulls big trees and water close by. reproduction Many mammals can be elusive to sighting, leaving Raccoons mate from February through March in Ohio. Typically only one litter is produced each year, only a trail of clues that they were present. -

Living with Wildlife - Flying Foxes Fact Sheet No

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE - FLYING FOXES FACT SHEET NO. 0063 Living with wildlife - Flying Foxes What are flying foxes? flying foxes use to mark their territory and to attract females during the mating season. Flying foxes, also known as fruit bats, are winged mammals belonging to the sub-order group of megabats. Unlike the smaller insectivorous microbats, the Do flying foxes carry diseases? animal navigates using their eye sight and smell, as opposed to echolocation, Like most wildlife and pets, flying foxes may carry diseases that can affect and feed on nectar, pollen and fruit. Flying foxes forage from over 100 humans. Australian Bat Lyssavirus can be transmitted directly from flying species of native plants and may supplement this diet with introduced plants foxes to humans. The risk of contracting Lyssavirus is extremely low, with found in gardens, orchards and urban areas. transmission only possible through direct contact of saliva from an infected Of the four species of flying foxes native to mainland Australia, three reside animal with a skin penetrating bite or scratch. in the Gladstone Region. These species include the grey-headed flying fox Flying foxes are natural hosts of the Hendra virus, however, there is no (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) and little red evidence that the virus can be transmitted directly to humans. It is believed flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). that the virus is transmitted from flying foxes to horses through exposure to All of these species are protected under the Nature Conservation Act urine or birthing fluids. Vaccination is the most effective way of reducing the 1992 and the grey-headed flying fox is also listed as ‘vulnerable’ under the risk of the virus infecting horses. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Controlling the Eastern Mole

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA9095 Controlling the Eastern Mole Dustin Blakey Introduction known about the Eastern Mole, and County Extension Agent successful control in landscapes Agriculture Few things in this world are requires a basic understanding of more frustrating than spending valu their biology. able time and money on a landscape Rebecca McPeake only to have it torn up by wildlife. Mole Biology Associate Professor and Moles’ underground habits aerate the Extension Wildlife soil and reduce grubs, but their Moles spend most of their lives Specialist digging is cause for homeowner underground feeding on invertebrate complaints, making them one of the animals living in the soil. A mole’s most destructive mammals that can diet sharply reflects the diversity of inhabit our landscapes. the fauna found in its environment. In Arkansas, moles primarily feed on earthworms, grubs and other inverte brates. Moles lack the dental struc ture to chew plant material (seeds, roots, etc.) for food and, as a result, subsist strictly as carnivores. Occasionally moles will cut surface vegetation and bring it down to their nest, as bedding, but this is not eaten. Figure 1. Rarely seen on the surface, moles are uniquely designed for their underground existence. Photo printed with permission by Ann and Rob Simpson. Contrary to popular belief, moles are not rodents. Mice, squirrels and gophers are all rodents. Moles are insectivores in the family Talpidae. Figure 2. Moles lack the dental structure This animal family survives by to chew plant material and subsist feeding on invertebrate prey. There mostly on earthworms and other invertebrates. are seven species of moles in North America, but the Eastern Mole Moles are well-adapted to living (Scalopus aquaticus L.) is the species underground. -

Bison Literature Review Biology

Bison Literature Review Ben Baldwin and Kody Menghini The purpose of this document is to compare the biology, ecology and basic behavior of cattle and bison for a management context. The literature related to bison is extensive and broad in scope covering the full continuum of domestication. The information incorporated in this review is focused on bison in more or less “wild” or free-ranging situations i.e.., not bison in close confinement or commercial production. While the scientific literature provides a solid basis for much of the basic biology and ecology, there is a wealth of information related to management implications and guidelines that is not captured. Much of the current information related to bison management, behavior (especially social organization) and practical knowledge is available through local experts, current research that has yet to be published, or popular literature. These sources, while harder to find and usually more localized in scope, provide crucial information pertaining to bison management. Biology Diet Composition Bison evolutional history provides the basis for many of the differences between bison and cattle. Bison due to their evolution in North America ecosystems are better adapted than introduced cattle, especially in grass dominated systems such as prairies. Many of these areas historically had relatively low quality forage. Bison are capable of more efficient digestion of low-quality forage then cattle (Peden et al. 1973; Plumb and Dodd 1993). Peden et al. (1973) also found that bison could consume greater quantities of low protein and poor quality forage then cattle. Bison and cattle have significant dietary overlap, but there are slight differences as well. -

Last Interglacial (MIS 5) Ungulate Assemblage from the Central Iberian Peninsula: the Camino Cave (Pinilla Del Valle, Madrid, Spain)

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 374 (2013) 327–337 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Last Interglacial (MIS 5) ungulate assemblage from the Central Iberian Peninsula: The Camino Cave (Pinilla del Valle, Madrid, Spain) Diego J. Álvarez-Lao a,⁎, Juan L. Arsuaga b,c, Enrique Baquedano d, Alfredo Pérez-González e a Área de Paleontología, Departamento de Geología, Universidad de Oviedo, C/Jesús Arias de Velasco, s/n, 33005 Oviedo, Spain b Centro Mixto UCM-ISCIII de Evolución y Comportamiento Humanos, C/Sinesio Delgado, 4, 28029 Madrid, Spain c Departamento de Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad Universitaria, 28040 Madrid, Spain d Museo Arqueológico Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid, Plaza de las Bernardas, s/n, 28801-Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain e Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), Paseo Sierra de Atapuerca, s/n, 09002 Burgos, Spain article info abstract Article history: The fossil assemblage from the Camino Cave, corresponding to the late MIS 5, constitutes a key record to un- Received 2 November 2012 derstand the faunal composition of Central Iberia during the last Interglacial. Moreover, the largest Iberian Received in revised form 21 January 2013 fallow deer fossil population was recovered here. Other ungulate species present at this assemblage include Accepted 31 January 2013 red deer, roe deer, aurochs, chamois, wild boar, horse and steppe rhinoceros; carnivores and Neanderthals Available online 13 February 2013 are also present. The origin of the accumulation has been interpreted as a hyena den. Abundant fallow deer skeletal elements allowed to statistically compare the Camino Cave fossils with other Keywords: Early Late Pleistocene Pleistocene and Holocene European populations. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Mammalian Predators Appropriating the Refugia of Their Prey

Mamm Res (2015) 60:285–292 DOI 10.1007/s13364-015-0236-y ORIGINAL PAPER When prey provide more than food: mammalian predators appropriating the refugia of their prey William J. Zielinski 1 Received: 30 September 2014 /Accepted: 20 July 2015 /Published online: 31 July 2015 # Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Białowieża, Poland (outside the USA) 2015 Abstract Some mammalian predators acquire both food and predators) may play disproportionately important roles in their shelter from their prey, by eating them and using the refugia communities. the prey construct. I searched the literature for examples of predators that exhibit this behavior and summarize their taxo- Keywords Predator–prey . Dens . Herbivore . Behavior . nomic affiliations, relative sizes, and distributions. I hypothe- Habitat . Resting . Foraging sized that size ratios of species involved in this dynamic would be near 1.0, and that most of these interactions would occur at intermediate and high latitudes. Seventeen species of Introduction Carnivorans exploited at least 23 species of herbivores as food and for their refugia. Most of them (76.4 %) were in the Mammals require food and most require shelter, either to pro- Mustelidae; several small species of canids and a few tect them from predators or from thermal stress. Carnivorous herpestids were exceptions. Surprisingly, the average mammals are unique in that they subsist on mobile food predator/prey weight ratio was 10.51, but few species of pred- sources which, particularly if these sources are vertebrates, ators were more than ten times the weight of the prey whose may build their own refuges to help regulate their body tem- refugia they exploit. -

The Adapted Ears of Big Cats and Golden Moles: Exotic Outcomes of the Evolutionary Radiation of Mammals

FEATURED ARTICLE The Adapted Ears of Big Cats and Golden Moles: Exotic Outcomes of the Evolutionary Radiation of Mammals Edward J. Walsh and JoAnn McGee Through the process of natural selection, diverse organs and organ systems abound throughout the animal kingdom. In light of such abundant and assorted diversity, evolutionary adaptations have spawned a host of peculiar physiologies. The anatomical oddities that underlie these physiologies and behaviors are the telltale indicators of trait specialization. Following from this, the purpose of this article is to consider a number of auditory “inventions” brought about through natural selection in two phylogenetically distinct groups of mammals, the largely fossorial golden moles (Order Afrosoricida, Family Chrysochloridae) and the carnivorous felids of the genus Panthera along with its taxonomic neigh- bor, the clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa). In the Beginning The first vertebrate land invasion occurred during the Early Carboniferous period some 370 million years ago. The primitive but essential scaffolding of what would become the middle and inner ears of mammals was present at this time, although the evolution of the osseous (bony) middle ear system and the optimization of cochlear fea- tures and function would play out over the following 100 million years. Through natural selection, the evolution of the middle ear system, composed of three small articu- lated bones, the malleus, incus, and stapes, and a highly structured and coiled inner ear, came to represent all marsupial and placental (therian) mammals on the planet Figure 1. Schematics of the outer, middle, and inner ears (A) and thus far studied. The consequences of this evolution were the organ of Corti in cross section (B) of a placental mammal. -

Late Eocene Potamogalidae and Tenrecidae (Mammalia) from the Sperrgebiet, Namibia

Late Eocene Potamogalidae and Tenrecidae (Mammalia) from the Sperrgebiet, Namibia Martin Pickford Sorbonne Universités (CR2P, UMR 7207 du CNRS, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle et Université Pierre et Marie Curie) case postale 38, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris. e-mail: < [email protected] > Abstract : The Late Eocene (Bartonian) Eocliff Limestone has yielded a rich, diverse and well- preserved micromammalian fauna which includes three tenrecoids, a chrysochlorid, several macroscelidids and at least eight taxa of rodents. The available cranio-dental and post-cranial elements reveal that the three tenrecoid species are closely related to potamogalids (one taxon) and to tenrecids (two taxa). The dichotomy between these two families probably occurred a long time before deposition of the Eocliff carbonate, possibly during the Palaeocene or even as early as the Late Cretaceous. The dentitions of the Eocliff potamogalid and tenrecids exhibit primitive versions of protozalambdodonty, in which the upper molars have clear metacones. Three new genera and species are described. Key Words : Potamogalidae, Tenrecidae, Zalambdodonty, Late Eocene, Namibia, Evolution To cite this paper: Pickford, M., 2015. Late Eocene Potamogalidae and Tenrecidae (Mammalia) from the Sperrgebiet, Namibia. Co mmunications of the Geological Survey of Namibia , 16, 114-152. Submitted in 2015. Introduction the suborder Tenrecoidea is not well represented in North Africa. The Late Eocene The discovery of Bartonian vertebrates Namibian fossils thus help to fill extensive in the Sperrgebiet, Namibia, is of major chronological and geographic gaps in the significance for throwing light on the evolution history and distribution of zalambdodont of African Palaeogene mammals, especially mammals in Africa, although the geographic that of rodents, tenrecoids and chrysochlorids position of the deposits from which they were (Pickford et al. -

Subterranean Mammals Show Convergent Regression in Ocular Genes and Enhancers, Along with Adaptation to Tunneling

RESEARCH ARTICLE Subterranean mammals show convergent regression in ocular genes and enhancers, along with adaptation to tunneling Raghavendran Partha1, Bharesh K Chauhan2,3, Zelia Ferreira1, Joseph D Robinson4, Kira Lathrop2,3, Ken K Nischal2,3, Maria Chikina1*, Nathan L Clark1* 1Department of Computational and Systems Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 2UPMC Eye Center, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 3Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, United States; 4Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, United States Abstract The underground environment imposes unique demands on life that have led subterranean species to evolve specialized traits, many of which evolved convergently. We studied convergence in evolutionary rate in subterranean mammals in order to associate phenotypic evolution with specific genetic regions. We identified a strong excess of vision- and skin-related genes that changed at accelerated rates in the subterranean environment due to relaxed constraint and adaptive evolution. We also demonstrate that ocular-specific transcriptional enhancers were convergently accelerated, whereas enhancers active outside the eye were not. Furthermore, several uncharacterized genes and regulatory sequences demonstrated convergence and thus constitute novel candidate sequences for congenital ocular disorders. The strong evidence of convergence in these species indicates that evolution in this environment is recurrent and predictable and can be used to gain insights into phenotype–genotype relationships. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25884.001 *For correspondence: [email protected] (MC); [email protected] (NLC) Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no The subterranean habitat has been colonized by numerous animal species for its shelter and unique competing interests exist. -

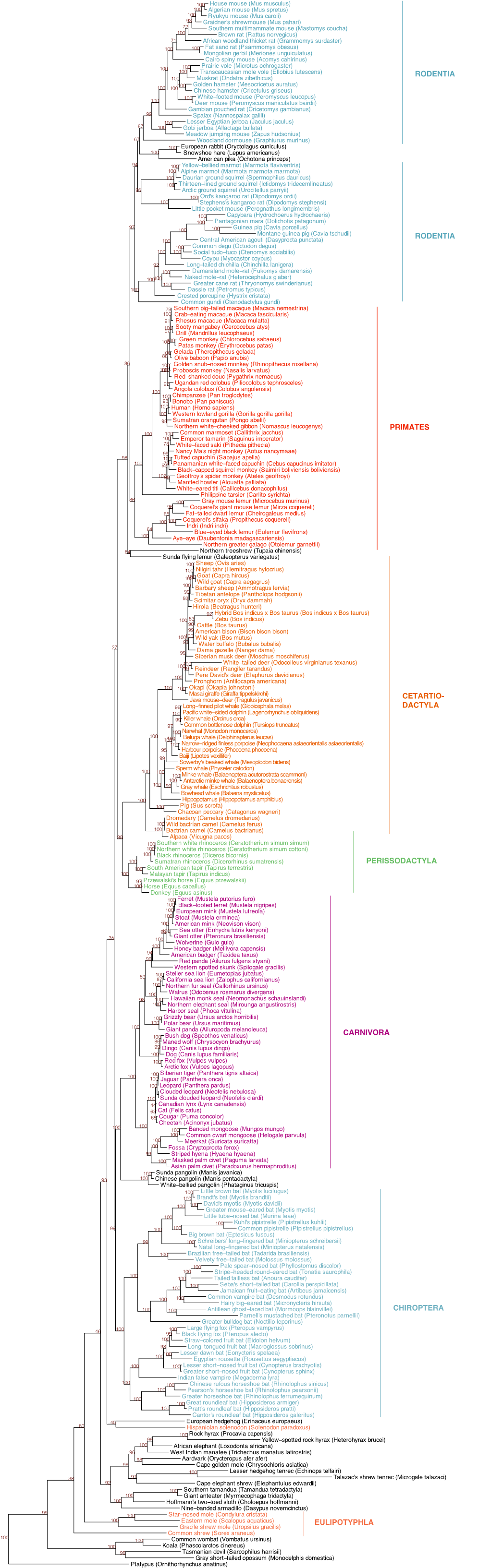

The Phylogenetic Roots of Human Lethal Violence José María Gómez1,2, Miguel Verdú3, Adela González-Megías4 & Marcos Méndez5

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature19758 The phylogenetic roots of human lethal violence José María Gómez1,2, Miguel Verdú3, Adela González-Megías4 & Marcos Méndez5 The psychological, sociological and evolutionary roots of 600 human populations, ranging from the Palaeolithic era to the present conspecific violence in humans are still debated, despite attracting (Supplementary Information section 9c). The level of lethal violence the attention of intellectuals for over two millennia1–11. Here we was defined as the probability of dying from intraspecific violence propose a conceptual approach towards understanding these roots compared to all other causes. More specifically, we calculated the level based on the assumption that aggression in mammals, including of lethal violence as the percentage, with respect to all documented humans, has a significant phylogenetic component. By compiling sources of mortality, of total deaths due to conspecifics (these sources of mortality from a comprehensive sample of mammals, were infanticide, cannibalism, inter-group aggression and any other we assessed the percentage of deaths due to conspecifics and, type of intraspecific killings in non-human mammals; war, homicide, using phylogenetic comparative tools, predicted this value for infanticide, execution, and any other kind of intentional conspecific humans. The proportion of human deaths phylogenetically killing in humans). predicted to be caused by interpersonal violence stood at 2%. Lethal violence is reported for almost 40% of the studied mammal This value was similar to the one phylogenetically inferred for species (Supplementary Information section 9a). This is probably the evolutionary ancestor of primates and apes, indicating that a an underestimation, because information is not available for many certain level of lethal violence arises owing to our position within species.