Gypsy/ Traveller Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun at Night Flamenco, Feast, and Politics

Sun At Night Flamenco, Feast, and Politics July 2–4, 2021 WKV #Park Side Gonzalo García Pelayo, Pedro G. Romero, Nueve Sevillas, 2020, film still OUTDOOR LIVE PROGRAM & LIVE STREAM Music, Performances, Lectures, Films, Talks, Workshop ... Daniel Baker, Francesco Careri / Stalker, Joy Charpentier, Georges Didi-Huberman, Pastora Filigrana, Robert Gabris, Delaine Le Bas, Leonor Leal, María Marín, Moritz Pankok, Gonzalo García Pelayo, María García Ruiz, Tomás de Perrate, Proyecto Lorca (Juan Jiménez, Antonio Moreno), Pedro G. Romero, Victoria Sacco, Marco Serrato, Evelyn Steinthaler, Sébastien Thiery / PEROU and others Registration: [email protected] Language: English Context: Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead. Una forma de ser 1 The Württembergischer Kunstverein is glad to finally announce the long-planned and often postponed program Sun At Night, which will take place as part of the exhibition Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead: Una forma de ser from July 2 to 4, 2021 in the Kunstverein's new and temporary open air platform, the Shared Space #Park Side. With a dense program of flamenco music and dance, performances, films, lectures, and a workshop, a central theme of the exhibition, the feast, will be reflected not only thematically but also as a practice. The program deals with the manifold relationships and interactions between flamenco, the transgressions and debauchery of the feast, and the political struggle of marginalized groups such as the Sinti and Roma. The entire outdoor program at the Kunstverein will be streamed live. With Georges Didi-Huberman, a renowned art historian and philosopher participates, who has been dealing with the influences of flamenco on the avant-gardes of the 20th century for a long time. -

Paradise Lost (4.65 Mb Pdf File)

Edited by Tímea Junghaus and Katalin Székely THE FIRST ROMA PAVILION LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2007 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 12 Foreword 13 Paradise Lost – The First Roma Pavilion by Tímea Junghaus 16 Statements 24 Second Site by Thomas Acton 30 Towards Europe’s First Nation by Michael M. Thoss 34 The Roma Pavilion in Venice – A Bold Beginning by Gottfried Wagner 36 Artists, Statements, Works Daniel BAKER 40 Tibor BALOGH 62 Mihaela CIMPEANU 66 Gabi JIMÉNEZ 72 András KÁLLAI 84 Damian LE BAS 88 Delaine LE BAS 100 Kiba LUMBERG 120 OMARA 136 Marian PETRE 144 Nihad Nino PUSˇIJA 148 Jenô André RAATZSCH 152 Dusan RISTIC 156 István SZENTANDRÁSSY 160 Norbert SZIRMAI - János RÉVÉSZ 166 Bibliography 170 Acknowledgements Foreword With this publication, the Open Society Institute, Allianz Kulturstiftung and the European Cultural Foundation announce The Open Society Institute, the Allianz Kulturstiftung and the European Cultural Foundation are pleased to sponsor the the First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale, which presents a selection of contemporary Roma artists from eight First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale. With artists representing eight countries, this is the first truly European European countries. pavilion in the Biennale's history, located in an exceptional space – Palazzo Pisani Santa Marina, a typical 16th-century Venetian palace in the city’s Canareggio district. This catalogue is the result of an initiative undertaken by the Open Society Institute’s Arts and Culture Network Program to find untapped talent and identify Roma artists who are generally unknown to the European art scene. During our A Roma Pavilion alongside the Biennale's national pavilions is a significant step toward giving contemporary Roma research, we contacted organisations, institutions and individuals who had already worked to create fair representations culture the audience it deserves. -

Delaine Cv 042020.Pages

Delaine Le Bas 1965 Born in Worthing, West Sussex, U.K. 1980 - 1986 West Sussex College Of Art & Design 1986 - 1988 St Martins School Of Art, M.A. Currently lives and works in Worthing. Selected Solo Exhibitions from 2009 2019 Tutis A Rinkeni Moola, Abri, Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London 2018 Untouchable Gypsy Witch, Transmission, Glasgow 2015 Say No to Identity Theft, Gallery8, Budapest Kushti Atchin Tan?, Galerie Kai Dikhas, Berlin 2014 Local Name: Unknown Gypsies?, Phoenix, Brighton, To Gypsyland, Bolton Musuem and Art Gallery, Bolton 2013 To Gypsyland, A Studio Practice and Archive Project, Metal, Peterborough To Gypsyland, A Studio Practice and Archive Project, 198, London 2012 O Brishindeskeriatar, The Cardiff Story, Cardiff 2011 Witch Hunt, Campbell Works, London Witch Hunt, Kai Dikhas, Aufbaus Haus, Berlin 2010 Witch Hunt, Context, Derry, Ireland Witch Hunt, Chapter, Cardiff 2009 Witch Hunt, ASPEX, Portsmouth Selected Group Exhibitions from 2009 2019 DE HEMATIZE IT! 4.Berliner Herbstsalon, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin FUTUROMA, Collateral event for the 58th Venice Biennale, Venice 2018 ANTI Athens Biennale, Athens Orlando at the Present Time, Charleston, Firle, West Sussex Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix www.yamamotokeiko.com Roma Spring: Art As Resistance, ERIAC, Berlin Come Out Now!, The First Roma Biennale, Gorki & Studio R, Berlin The Right To Look, Gallery Szara Kamienica, Krakow 2017 3. Berliner Herbstsalon, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin Scharfstellen_1, <rotor> Association For Contemporary Art, Graz Romani History X, Maxim Gorki Theatre, -

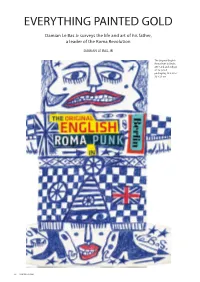

Damian Les Bas in Raw Vision

EVERYTHING PAINTED GOLD Damian Le Bas Jr surveys the life and art of his father, a leader of the Roma Revolution DAMIAN LE BAS, JR The Original English Roma Punk In Berlin, 2017, ink and collage on recycled packaging, 13 x 9 in. / 32 x 23 cm 38 RAW VISION 100 The Council Tenants, 1990, oil pastel on paper, 29.5 x 21.5 in. / 75 x 55cm Damian Le Bas with Roma Armee, Berlin, 2017, photo: Delaine Le Bas amian Le Bas is a tribe of one”, remarked the The Council Tenants, in which wide-eyed faces stared from writer, critic and jazz singer George Melly in the windows of orange and purple terraced homes, and “D1992. He had his reasons. Melly was opening on display was a vivid portrait of Liz Taylor and Richard a show of works by Le Bas at the Horsham Arts Centre, Burton, which Melly later acquired. The family of Le Bas’ a glass-fronted theatre in one of the wealthiest corners of wife (and my mother) Delaine, were in attendance, so the southern England. The invitation featured a drawing called private view was full of Gypsies. Someone pointed at RAW VISION 100 39 above: Gypsyland Europa (detail), 2016, ink on printed map, opposite: Roma Armee drawings for an animation project, 2017, 53 x 37 in. / 136 x 94 cm ink on paper, 8 x 6 in. / 21 x 14.5 cm George Melly’s ring and shouted, “Dik at the fawni mush, to London as well as Derbyshire Romany ancestry. When he it’s got a yawk in it!” (“Look at the ring man, it’s got an eye was ten, the family relocated to West Sussex, and by in it!”). -

On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency Suzana

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 16 On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency Reconciliation, Shame, On Productive On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency Suzana Milevska (Ed.) On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency Suzana Milevska (Ed.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) Volume 16 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present this new volume in the publication series of the Acad- emy of Fine Arts Vienna. The series, published in cooperation with our highly committed partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contempo- rary thought about art practices and art theories. The volumes in the series are composed of collected contributions on subjects that form the focus of dis- course in terms of art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is pub- lished in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Authors of high international repute are invited to write contri- butions dealing with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities, such as international conferences, lecture series, institute-specific research focuses, or research projects, serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. With On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency we are launching volume sixteen of the series. Suzana Milevska, the editor of this publication, was Endowed Professor for Central and South Eastern Art Histories at the Academy from 2013 until 2015. -

Meet Your Neighbours

Meet Your Neighbours Contemporary Roma Art from Europe Meet Your Neighbours Contemporary Roma Art from Europe Arts and Culture Network Program 2006 Acknowledgement This collection of texts and artworks is the result of a mission undertaken by the Open Society Institute’s Arts and Culture Network Program. The primary goal of this initiative was to find untapped talent and identify Roma artists who are generally unknown to the European art scene. During research and collection, we contacted those organizations, institutions and individuals who have already acted in this spirit, and have done their best to attain recognition for Roma art, help the Roma to appear in cultural life and to create their fair representation. This catalogue could not have been created without expert advice and suggestions from the OSI Budapest team. We feel indebted to all those who have generously devoted time to participating in the project, in particular: The artists who allowed us to publish their biography and reproductions of their works. Grace Acton; Prof. Thomas Acton, Professor of Romani Studies, University of Greenwich; Daniel Baker, artist; Rita Bakradze, program assistant, OSI Budapest, Arts and Culture Network Program; Ágnes Daróczi, minority studies expert of the Hungarian Institute of Culture, Budapest; Andrea Csanádi, program Manager, OSI Budapest, Arts and Culture Network Program; Jana Horváthová, Ph.D., Director of the Museum of Romani Culture, Brno; Guy de Malingre; Nihad Nino Pusija, artist, photographer; Mgr. Helena Sadilková, curator of the Museum of Romani Culture, Brno; Gheorghe Sarau, School inspector for Roma in the Direction for Education in Languages of Ethnic Minorities, univ. -

Art Criticism in Times of Populism and Nationalism. 52Nd International

Appendix AUTHOR‘S BIOGRAPHIES ILLUSTRATIONS NOTES OF THE EDITORS CONTRIBUTORS TO THE CONGRESS IMPRINT AUTHOR‘S BIOGRAPHIES 295 Florian Arnold Florian Arnold studied philosophy, German language and literature in Heidelberg and Paris. After a doctorate in philosophy (Heidelberg) and a second doctorate in Design Studies at the University of Arts and Design Offenbach, he currently teaches at the Stutt- gart State Academy of Art and Design as academic staff. He is editor of the Philosophische Rundschau and scientific advisor of DIVERSUS e. V. Sabeth Buchmann Sabeth Buchmann (Berlin/Vienna) is an art historian and critic, as well as a pro- fessor of modern and post-modern art history at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Together with Helmut Draxler, Clemens Krümmel and Susanne Leeb, she publishes »PoLYpeN«, a series on art criticism and political theory published by b_books (Berlin). Since 1998 she has been a member of the advisory board of the journal Texte zur Kunst. Selection of publications: Ed. with Ilse Lafer and Constanze Ruhm: Putting Rehearsals to the Test. Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film. Theater, Theory, and Politics (2016); co-author with Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz: Hélio Oiticica & Neville D’Almeida, Experiments in Cosmococa (2013); Denken gegen das Denken. Production, Technology, Subjektivität bei Sol LeWitt, Yvonne Rainer und Helio Oiticica (2007). Elke Buhr Elke Buhr is editor-in-chief of Monopol, the magazine for art and life, in Berlin. She studied German Language, history and journalism in Bochum, Bologna and Dort- mund and worked as a trainee at Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne. As an editor in the Feuilleton of the Frankfurter Rundschau, she was responsible for the art section and dealt with all aspects of contemporary pop culture. -

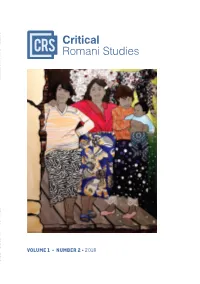

VOLUME 1 • NUMBER 2 • 2018 and the Academy

CRITICAL ROMANI STUDIES CRITICAL Foreword Articles Power and Hierarchy among Finnish Kaale Roma: Insights on Integration and Inclusion Processes Marko Stenroos The Class-to-Race Cascade: Interrogating Racial Neoliberalism in Romani Studies and Urban Policy in Budapest’s Eighth District Jonathan McCombs Roma, Adequate Housing, and the Home: Construction and Impact of a Narrative in EU Policy Documents Silvia Cittadini Nomadism in Research on Roma Education Solvor Mjøberg Lauritzen From Reflexivity to Collaboration: Changing Roles of a Non-Romani Scholar, Activist, and Performer Carol Silverman Non-Romani Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity: Queer(y)ing One’s Own Privilege Lucie Fremlova Power Hierarchies between the Researcher and Informants: Critical Observations during Fieldwork in a Roma Settlement Jekatyerina Dunajeva Arts and Culture Decolonizing the Arts: A Genealogy of Romani Stereotypes in the Louvre and Prado Collections Sarah Carmona From Gypsyland With Love: Review of the Theater Play Roma Armee 1 • NUMBER 2 2018 VOLUME Katarzyna Pabijanek Book Reviews Giovanni Picker. 2017. Racial Cities: Governance and the Segregation of Romani People in Urban Europe. London: Routledge. Angéla Kóczé Andrew Ryder. 2017. Sites of Resistance. Gypsies, Roma and Travellers in School, Community VOLUME 1 • NUMBER 2 • 2018 and the Academy. London: UCL IOE Press. Miklós Hadas Aims and Scope Critical Romani Studies is an international, interdisciplinary, peer-reviewed journal providing a forum for activist-scholars to critically examine racial oppressions, different forms of exclusion, inequalities, and human rights abuses of Roma. Without compromising academic standards of evidence collection Editors and analysis, the Journal seeks to create a platform to critically engage with academic knowledge production, and generate critical academic and policy Maria Bogdan knowledge targeting – amongst others – scholars, activists, and policymakers. -

Delaine Cv Performance 022021

Delaine Le Bas 1965 Born in Worthing, West Sussex, U.K. 1980 - 1986 West Sussex College Of Art & Design 1986 - 1988 St Martins School Of Art, M.A. Lives and works in Worthing, East Sussex. Selected Performance 2019 Witch Hunt III - News from Gypsyland for DE HEMATIZE IT! 4.Berliner Herbstsalon, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin Roma Futurism, Romanian Cultural Institute, London Romani Embassy for FUTUROMA, Roma Pavillion, a collateral event for 58th Venice Biennale Roma Futurism for FUTUROMA, Roma Pavillion, a collateral event for 58th Venice Biennale Roma Futurism, Central European University, Budapest Tutis A Rinkeni Moola, Abri, Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London 2018 From The Forests Of Grief We Grow Like Shrubs Of Gold, Galerie en Kronerpark, Berlin This Head Of A Gypsy Can Speak For Herself, ANTI Athens Biennale, Athens Medea Rominji, Tag Aufbau Haus Berlin, Berlin In The Forest Of Grief I Grew Like A Shrub Of Gold, Charleston Firle, U.K Romani Embassy for Come Out Now! The First Roma Biennale, Gorki, Berlin Hilton Zimmer 437, for Come Out Now! The First Roma Biennale Gorki Berlin The Long Night Of Coming Out, for Come Out Now! The First Roma Biennale, Studio R Gorki Berlin 2017 A Question Of Reflection?, for 3. Berliner Herbstsalon, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin Romani Embassy for Romani History X, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin Defiance, - Propositions for Non-Facist Living - Video - Bak, Utrecht Romani Embassy, Alexanderplatz, Berlin Hysterical Oracle, Basement Arts Project, Leeds Kali Rising, Part II Jaw Dikh!,Czarna Gora, Poland Romani Embassy, -

Delaine Le Bas

Delaine Le Bas Born in Worthing, West Sussex, July 17th 1965 GROUP AND SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2008 Solo show, Galerie Sara Guedj, Paris 2007 Paradise Lost, The First Roma Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy Chavi, Novas Contemporary Urban Centre, London, U.K Refusing Exclusion, Prague Biennale 3, Prague, Czechoslovakia Underbelly Deptford X, Deptford Market Traders Yard, London, U.K O Dreamland, Greatstone, Kent, U.K Internal Guidance Systems, Tag Gallery, Nashville, TN, U.S.A 2006 Contemporary Gypsy, Mascalls Gallery, Paddock Wood, Kent, U.K International Festival d’Art Singulier, Roquevaire, France Internal Guidance Systems, The Outsider Centre, MN, U.S.A Outsider Art, (Moscow Museum of Outsider Art in collaboration with The City Of Bar), Cultural Centre Vladimir Popovic Spanac, Bar, Montenegro. Second Site, Abbot’s Hall, Museum of East Anglian Life, Stowmarket, Suffolk, U.K Internal Guidance Systems, N4th Gallery, Albuquerque, NM, U.S.A Second Site, The Supper Rooms, Appleby, U.K Paper World, Transition, London, U.K Second Site, The West Park Centre, Leeds, U.K Second Site, Stephen Lawrence Gallery, Greenwich, London, U.K Internal Guidance Systems, Pearl and Wonder Ballroom Locations, Mark Woolley Gallery, Portland, Oregon, U.S.A Race, Class, Gender # Character, American Visionary Art Museum, Baltimore, U.S.A 2005 Acid Drops & Sugar Candy, Transition, London, U.K Acid Drops & Sugar Candy, Fosterart, London, U.K The Art of the Book, University of Missouri, St Louis, U.S.A Race, Class, Gender # Character, American Visionary Art Museum, -

Lidija Mirković

DIKH! 1 Look! What is Important? Lidija Mirković “Have a look into my life!“ is based on Romani Čhib, a largely unknown with regard to housing, health, employment and education confirm a Who We Are, 2011—2014 language, which is spoken by millions of people in Europe. large-scale discrimination. We have asked Romnia and Roma from all over Europe to submit the Lidija Mirković, * near Belgrade, studied social science and audiovisual three Romani words which are most significant to them. More than Some of the contributors regret that they no longer have a good communication at the University of Duisburg. As an artist with Roma- 350 contributions arrived – from Finland, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Czech command of Romani Čhib due to socio-political circumstances. They try origins, she documents the every day life of Gypsies (as she calls also Republic, Spain, Great Britain, France, Hungary, Serbia, Germany, all the more to maintain the remnants of the language and to pass them herself) in Europe with photographs and short films. She is co-founder of Austria, Bosnia, Kosovo, Albania, Macedonia and Romania. on to their children. The Romani language has many regional variations. the International Romani Film Commission (IRFC). To this day there is no standard Romani (neither oral nor written) The selected words portray values which are important to everybody: recognised by all groups. This is why we have adopted all contributions WWW.HAYMATFILM.COM love, health, family, children, happiness, work and a home. Yet the Roma’s without any changes. “Who We Are“ shows a different image of Romnia/Roma, with activists, chances of enjoying these values are far lower. -

Newspaper FUTUROMA

COLLATERAL EVENT OF THE 58TH INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION — LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA CURATED BY DANIEL BAKER COMMISSIONED BY ERIAC — FONDAMENTA ZATTERE ALLO SPIRITO SANTO 417 11 MAY - 24 NOVEMBER 2019 ARTISTS: CELIA BAKER JÁN BERKY MARCUS-GUNNAR PETTERSSON ÖDÖN GYÜGYI BILLY KERRY KLÁRA LAKATOS DELAINE LE BAS VALÉRIE LERAY EMÍLIA RIGOVÁ MARKÉTA ŠESTÁKOVÁ SELMA SELMAN DAN TURNER ALFRED ULLRICH LÁSZLÓ VARGA ERIAC EUROPEAN ROMA INSTITUTE COMMISSIONED BY COMMISSIONED FOR ARTS AND CULTURE photo credit: Daniel Baker INTERVIEW CURATOR, DANIEL BAKER Daniel Baker is a Romani Gypsy artist, of La Biennale di Venezia – “Paradise Lost” and researcher, and curator. Originally from Kent, “Call the Witness,” which took place during the now based in London, his work is exhibited 52nd and 54th International Art Exhibition of WITH THE COMMISSIONERS internationally and can be found in collections La Biennale di Venezia, respectively. In 2018, across the globe. Baker earned a PhD in after hosting an open call for curators, an 2011 from the Royal College of Art, with his international jury consisting of Professor Dr. Ethel dissertation, “Gypsy Visuality: Gell’s Art Nexus Brooks, Tony Gatlif, Miguel Ángel Vargas, and OF FUTUROMA and its Potential for Artists,” after previously ERIAC management selected him to curate the earning a MA in Sociology/Gender and Ethnic Roma Collateral Event. TIMEA JUNGHAUS Studies from Greenwich University, and a BA (Hons) in Fine Art from Ravensbourne College of Baker’s work examines the role of art in the WHAT IS THE HISTORY OF THE it is to think beyond national Art and Design. enactment of social agency through an eclectic PRESENCE OF ROMA ART AT THE representations.