In Romani Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

SIM Newsletter 5

SIM NEWSLETTER | Issue 5 5 SIM Newsletter Summer 2014 Credits:Arnold Rog Figure 1Credits: Arnold.rog/nl[Type a quote from the document or the summary of an interesting point. IN THIS ISSUE You can position the text box anywhere in the document. Use the Drawing Tools tab to change the formatting of the pull quote text box.] Afterthoughts By Jenny Goldschmidt, director of the Netherlands Institute of Human Rights Leaving SIM after 10 years, even when it is transitional justice to the implications of not a final goodbye, is not an easy moment. multiple identities of citizens, affect states, National Human Rights Institute Of course it is not easy to leave a high level, societies and individuals and have important creative and committed team but it is also implications for human rights. This demands Receives A-Status! difficult to be aware of the fact that the a solid theoretical rethinking of basic In May 2014, The Dutch National Institute for urgency of the mission of SIM is still there. concepts and at the same time an open eye Human Rights has received an A-status from the for practical implications in particular for the International Coordinating Committee of National According to the Statute of, as it then was, so-called vulnerable groups. Human Rights Institutions. Page 2 the Foundation SIM, the aim is to conduct research, collect and disseminate information and encourage interest in promotion and protection of human rights, both national and international. SIM was established by NGO members who felt that Events at SIM: Impressions the human rights defenders and advocates Read about the presentation of the Book needed accurate, reliable and innovative ‘Mensenrechten in Beweging’, a seminar on research and data to be successful. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

National Roma Integration Strategies

err C EUROPEAN ROMA RIGHTS CENTRE The European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) is an international public interest law organisation working to combat anti- Roma Rights Romani racism and human rights abuse of Roma. The approach of the ERRC involves strategic litigation, international Journal of the european roma rights Centre advocacy, research and policy development and training of Romani activists. The ERRC has consultative status with the Council of Europe, as well as with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. The ERRC has been the recipient of numerous awards for its efforts to advance human rights respect of Roma: The 2013 PL Foundation Freedom Prize; the 2012 Stockholm Human Rights Award, awarded jointly to the ERRC and Tho- mas Hammarberg; in 2010, the Silver Rose Award of SOLIDAR; in 2009, the Justice Prize of the Peter and Patricia Gruber Foundation; in 2007, the Max van der Stoel Award given by the High Commissioner on National Minorities and the Dutch Foreign Ministry; and in 2001, the Geuzenpenning Award (the Geuzen medal of honour) by Her Royal Highness Princess Margriet of the Netherlands; Board of Directors Robert Kushen – (USA - Chair of the Board) | Dan Pavel Doghi (Romania) | James A. Goldston (USA) | Maria Virginia Bras Gomes (Portugal) | Jeno˝ Kaltenbach (Hungary) I Abigail Smith, ERRC Treasurer (USA) Executive Director Dezideriu Gergely Staff Adam Weiss (Legal Director) | Andrea Jamrik (Financial Officer) | Andrea Colak (Lawyer) | Anna Orsós (Pro- grammes Assistant) | Anca Sandescu (Human Rights Trainer) -

Sun at Night Flamenco, Feast, and Politics

Sun At Night Flamenco, Feast, and Politics July 2–4, 2021 WKV #Park Side Gonzalo García Pelayo, Pedro G. Romero, Nueve Sevillas, 2020, film still OUTDOOR LIVE PROGRAM & LIVE STREAM Music, Performances, Lectures, Films, Talks, Workshop ... Daniel Baker, Francesco Careri / Stalker, Joy Charpentier, Georges Didi-Huberman, Pastora Filigrana, Robert Gabris, Delaine Le Bas, Leonor Leal, María Marín, Moritz Pankok, Gonzalo García Pelayo, María García Ruiz, Tomás de Perrate, Proyecto Lorca (Juan Jiménez, Antonio Moreno), Pedro G. Romero, Victoria Sacco, Marco Serrato, Evelyn Steinthaler, Sébastien Thiery / PEROU and others Registration: [email protected] Language: English Context: Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead. Una forma de ser 1 The Württembergischer Kunstverein is glad to finally announce the long-planned and often postponed program Sun At Night, which will take place as part of the exhibition Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead: Una forma de ser from July 2 to 4, 2021 in the Kunstverein's new and temporary open air platform, the Shared Space #Park Side. With a dense program of flamenco music and dance, performances, films, lectures, and a workshop, a central theme of the exhibition, the feast, will be reflected not only thematically but also as a practice. The program deals with the manifold relationships and interactions between flamenco, the transgressions and debauchery of the feast, and the political struggle of marginalized groups such as the Sinti and Roma. The entire outdoor program at the Kunstverein will be streamed live. With Georges Didi-Huberman, a renowned art historian and philosopher participates, who has been dealing with the influences of flamenco on the avant-gardes of the 20th century for a long time. -

Paradise Lost (4.65 Mb Pdf File)

Edited by Tímea Junghaus and Katalin Székely THE FIRST ROMA PAVILION LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2007 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 12 Foreword 13 Paradise Lost – The First Roma Pavilion by Tímea Junghaus 16 Statements 24 Second Site by Thomas Acton 30 Towards Europe’s First Nation by Michael M. Thoss 34 The Roma Pavilion in Venice – A Bold Beginning by Gottfried Wagner 36 Artists, Statements, Works Daniel BAKER 40 Tibor BALOGH 62 Mihaela CIMPEANU 66 Gabi JIMÉNEZ 72 András KÁLLAI 84 Damian LE BAS 88 Delaine LE BAS 100 Kiba LUMBERG 120 OMARA 136 Marian PETRE 144 Nihad Nino PUSˇIJA 148 Jenô André RAATZSCH 152 Dusan RISTIC 156 István SZENTANDRÁSSY 160 Norbert SZIRMAI - János RÉVÉSZ 166 Bibliography 170 Acknowledgements Foreword With this publication, the Open Society Institute, Allianz Kulturstiftung and the European Cultural Foundation announce The Open Society Institute, the Allianz Kulturstiftung and the European Cultural Foundation are pleased to sponsor the the First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale, which presents a selection of contemporary Roma artists from eight First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale. With artists representing eight countries, this is the first truly European European countries. pavilion in the Biennale's history, located in an exceptional space – Palazzo Pisani Santa Marina, a typical 16th-century Venetian palace in the city’s Canareggio district. This catalogue is the result of an initiative undertaken by the Open Society Institute’s Arts and Culture Network Program to find untapped talent and identify Roma artists who are generally unknown to the European art scene. During our A Roma Pavilion alongside the Biennale's national pavilions is a significant step toward giving contemporary Roma research, we contacted organisations, institutions and individuals who had already worked to create fair representations culture the audience it deserves. -

2020 Commencement Program.Pdf

Commencement MAY 2020 WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friends: This is an occasion of profoundly mixed emotions for all of us. On one hand, there is the pride, excitement, and immeasurable hope that come with the culmination of years of effort and success at the University of Connecticut. But on the other hand, there is the recognition that this year is different. For the first time since 1914, the University of Connecticut is conferring its graduate and undergraduate degrees without our traditional ceremonies. It is my sincere hope that you see this moment as an opportunity rather than a misfortune. As the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus observed, “Difficulties show us who we are.” This year our University, our state, our nation, and indeed our world have faced unprecedented difficulties. And now, as you go onward to the next stage of your journey, you have the opportunity to show what you have become in your time at UConn. Remember that the purpose of higher education is not confined to academic achievement; it is also intended to draw from within those essential qualities that make each of us an engaged, fully-formed individual – and a good citizen. There is no higher title that can be conferred in this world, and I know each of you will exemplify it, every day. This is truly a special class that will go on to achieve great things. Among your classmates are the University’s first Rhodes Scholar, the largest number of Goldwater scholars in our history, and outstanding student leaders on issues from climate action to racial justice to mental health. -

Year Book of the Holland Society of New-York

w r 974.7 PUBLIC LIBRARY M. L, H71 FORT WAYNE & ALLEM CO., IND. 1916 472087 SENE^AUOGV C0L.L-ECT!0N EN COUNTY PUBLIC lllllilllllilll 3 1833 01147 7442 TE^R BOOK OF The Holland Society OF New Tork igi6 PREPARED BY THE RECORDING SECRETARY Executive Office 90 West Street new york city Copyright 1916 The Holland Society of New York : CONTENTS DOMINE SELYNS' RECORDS: PAGE Introduction I Table of Contents 2 Discussion of Previous Editions 10 Text 21 Appendixes 41 Index 81 ADMINISTRATION Constitution 105 By-Laws 112 Badges 116 Accessions to Library 123 MEMBERSHIP: 472087 Former Officers 127 Committees 1915-16 142 List of Members 14+ Necrology 172 MEETINGS: Anniversary of Installation of First Mayor and Board of Aldermen 186 Poughkeepsie 199 Smoker 202 Hudson County Branch 204 Banquet 206 Annual Meeting 254 New Officers, 1916 265 In Memoriam 288 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Gerard Beekman—Portrait Frontispiece New York— 1695—Heading Cut i Selyns' Seal— Initial Letter i Dr. James S. Kittell— Portrait 38 North Church—Historic Plate 43 Map of New York City— 1695 85 Hon. Francis J. Swayze— Portrait 104 Badge of the Society 116 Button of the Society 122 Hon. William G. Raines—Portrait 128 Baltus Van Kleek Homestead—Heading Cut. ... 199 Eagle Tavern at Bergen—Heading Cut 204 Banquet Layout 207 Banquet Ticket 212 Banquet Menu 213 Ransoming Dutch Captives 213 New Amsterdam Seal— 1654 216 New York City Seal— 1669 216 President Wilson Paying Court to Father Knick- erbocker 253 e^ c^^ ^ 79c^t'*^ C»€^ THE HOLLAND SOCIETY TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction. Description and History of the Manuscript Volume. -

Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2002 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, July 2004 Copyright © 2002 by Ian Hancock, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Michael Zimmermann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Guenter Lewy, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Mark Biondich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Denis Peschanski, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Viorel Achim, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by David M. Crowe, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................i Paul A. Shapiro and Robert M. Ehrenreich Romani Americans (“Gypsies”).......................................................................................................1 Ian -

Delaine Cv 042020.Pages

Delaine Le Bas 1965 Born in Worthing, West Sussex, U.K. 1980 - 1986 West Sussex College Of Art & Design 1986 - 1988 St Martins School Of Art, M.A. Currently lives and works in Worthing. Selected Solo Exhibitions from 2009 2019 Tutis A Rinkeni Moola, Abri, Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London 2018 Untouchable Gypsy Witch, Transmission, Glasgow 2015 Say No to Identity Theft, Gallery8, Budapest Kushti Atchin Tan?, Galerie Kai Dikhas, Berlin 2014 Local Name: Unknown Gypsies?, Phoenix, Brighton, To Gypsyland, Bolton Musuem and Art Gallery, Bolton 2013 To Gypsyland, A Studio Practice and Archive Project, Metal, Peterborough To Gypsyland, A Studio Practice and Archive Project, 198, London 2012 O Brishindeskeriatar, The Cardiff Story, Cardiff 2011 Witch Hunt, Campbell Works, London Witch Hunt, Kai Dikhas, Aufbaus Haus, Berlin 2010 Witch Hunt, Context, Derry, Ireland Witch Hunt, Chapter, Cardiff 2009 Witch Hunt, ASPEX, Portsmouth Selected Group Exhibitions from 2009 2019 DE HEMATIZE IT! 4.Berliner Herbstsalon, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin FUTUROMA, Collateral event for the 58th Venice Biennale, Venice 2018 ANTI Athens Biennale, Athens Orlando at the Present Time, Charleston, Firle, West Sussex Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix www.yamamotokeiko.com Roma Spring: Art As Resistance, ERIAC, Berlin Come Out Now!, The First Roma Biennale, Gorki & Studio R, Berlin The Right To Look, Gallery Szara Kamienica, Krakow 2017 3. Berliner Herbstsalon, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin Scharfstellen_1, <rotor> Association For Contemporary Art, Graz Romani History X, Maxim Gorki Theatre, -

Roma Screenplay

IN ENGLISH ROMA Written and Directed by Alfonso Cuarón Dates in RED are meant only as a tool for the different departments for the specific historical accuracy of the scenes and are not intended to appear on screen. Thursday, September 3rd, 1970 INT. PATIO TEPEJI 21 - DAY Yellow triangles inside red squares. Water spreading over tiles. Grimy foam. The tile floor of a long and narrow patio stretching through the entire house: On one end, a black metal door gives onto the street. The door has frosted glass windows, two of which are broken, courtesy of some dejected goalee. CLEO, Cleotilde/Cleodegaria Gutiérrez, a Mixtec indigenous woman, about 26 years old, walks across the patio, nudging water over the wet floor with a squeegee. As she reaches the other end, the foam has amassed in a corner, timidly showing off its shiny little white bubbles, but - A GUSH OF WATER surprises and drags the stubborn little bubbles to the corner where they finally vanish, whirling into the sewer. Cleo picks up the brooms and buckets and carries them to - THE SMALL PATIO - Which is enclosed between the kitchen, the garage and the house. She opens the door to a small closet, puts away the brooms and buckets, walks into a small bathroom and closes the door. The patio remains silent except for a radio announcer, his enthusiasm melting in the distance, and the sad song of two caged little birds. The toilet flushes. Then: water from the sink. A beat, the door opens. Cleo dries her hands on her apron, enters the kitchen and disappears behind the door connecting it to the house. -

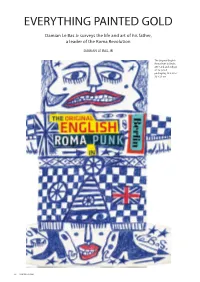

Damian Les Bas in Raw Vision

EVERYTHING PAINTED GOLD Damian Le Bas Jr surveys the life and art of his father, a leader of the Roma Revolution DAMIAN LE BAS, JR The Original English Roma Punk In Berlin, 2017, ink and collage on recycled packaging, 13 x 9 in. / 32 x 23 cm 38 RAW VISION 100 The Council Tenants, 1990, oil pastel on paper, 29.5 x 21.5 in. / 75 x 55cm Damian Le Bas with Roma Armee, Berlin, 2017, photo: Delaine Le Bas amian Le Bas is a tribe of one”, remarked the The Council Tenants, in which wide-eyed faces stared from writer, critic and jazz singer George Melly in the windows of orange and purple terraced homes, and “D1992. He had his reasons. Melly was opening on display was a vivid portrait of Liz Taylor and Richard a show of works by Le Bas at the Horsham Arts Centre, Burton, which Melly later acquired. The family of Le Bas’ a glass-fronted theatre in one of the wealthiest corners of wife (and my mother) Delaine, were in attendance, so the southern England. The invitation featured a drawing called private view was full of Gypsies. Someone pointed at RAW VISION 100 39 above: Gypsyland Europa (detail), 2016, ink on printed map, opposite: Roma Armee drawings for an animation project, 2017, 53 x 37 in. / 136 x 94 cm ink on paper, 8 x 6 in. / 21 x 14.5 cm George Melly’s ring and shouted, “Dik at the fawni mush, to London as well as Derbyshire Romany ancestry. When he it’s got a yawk in it!” (“Look at the ring man, it’s got an eye was ten, the family relocated to West Sussex, and by in it!”).