Extortion in Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to the Greek Government on the Visit to Greece Carried out By

CPT/Inf (2020) 15 Report to the Greek Government on the visit to Greece carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 28 March to 9 April 2019 The Greek Government has requested the publication of this report and of its response. The Government’s response is set out in document CPT/Inf (2020) 16. Strasbourg, 9 April 2020 - 2 - CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 4 I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 8 A. The visit, the report and follow-up.......................................................................................... 8 B. Consultations held by the delegation and co-operation encountered .................................. 9 C. Immediate observations under Article 8, paragraph 5, of the Convention....................... 10 D. National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) ............................................................................... 11 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT AND ACTION PROPOSED .............................. 12 A. Prison establishments ............................................................................................................. 12 1. Preliminary remarks ........................................................................................................ 12 2. Ill-treatment .................................................................................................................... -

Criminal Victimisation in Greece and the Fear of Crime: a 'Paradox' for Interpretation

International Review of Victimology. 2009, Vol. 16, pp. 277–300 0269-7580/09 $10 © A B Academic Publishers - Printed in Great Britain CRIMINAL VICTIMISATION IN GREECE AND THE FEAR OF CRIME: A 'PARADOX' FOR INTERPRETATION CHRISTINA ZARAFONITOU Panteion University, Greece* ABSTRACT The measurement of victimisation was rare and sporadic in Greece until 2005 when it was included in the EU International Crime Survey (EUICS). Many findings are highly interesting as for example those concerning corruption. There are also high ratings of feeling unsafe among the inhabitants of Greece, in particular those in Athens, in spite of the relatively low rates of their victimisation. This paper focuses on this point, trying to reveal the factors which could explain this 'paradox'. Keywords: Victimisation — fear of crime — satisfaction with the police — quality of life INTRODUCTION Victimisation surveys have been rare and sporadic in Greece until 2005 when they were included in the European victimisation survey (Van Dijk et al., 2007a; 2007b: p. 30). At the national level, only one victimisation survey has been carried out, in 2001 (Karydis, 2004) but this theme has frequently been examined in the framework of surveys on fear of crime which were carried out in Athens during the last decade (Zarafonitou, 2002, 2004; Zarafonitou and Courakis, 2009)1. The most important observation which emerged from those was the relatively low levels of victimisation of Greek citizens in comparison to the high levels of fear of crime revealed. In order for this 'paradox' to be explained, a conceptualisation of fear of crime (Vanderveen, 2006: p. 28) is necessary as well as looking at its attributed 'social meaning'2, in the context of the general social framework in which social attitudes are shaped and manifested. -

New Ladies Joining the Fleet

THE DANSHIP NEWS A SEMI-ANNUAL EDITION OF DANAOS SHIPPING CO. LTD. ISSUE #5, JUNE 2013 New ladies joining the fleet The trends of the global market are changing rapidly and the extended recession period of the container industry is continuing. Danaos could not let the opportunity slip and as such added two new acquisitions to our fleet . Our first acquisition joined our fleet in May. The M/V “AMALIA C”, a 2,452 TEU, geared Container vessel built in 1998, was delivered in Singapore. With the delivery of the M/V “AMALIA C”, Danaos is entering in a specific sector i.e. that of the geared feeder fleet, an area which has remained challenging, throughout the “dry spell” of the container industry. Our second Lady, the M/V NILEDUTCH ZEBRA, a 2,526 TEU, 2001 built geared container vessel, joined our fleet in mid-June and was delivered in Rotterdam. Consequently, Danaos sold four of our fleet's older vessels (Henry, Independence, Pride, MV Honour) for demolition purposes and replaced them with new acquisitions, mainly coming form the second-hand S&P market. THE NEWSPAPER IS PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER Message from Message from the President & CEO the Senior Vice President & COO Dear Colleagues, ÄÇÌÇÔÑÇÓ ÊÏÕÓÔÁÓ The "Father of Danaos", Mr. Dimitris Coustas has passed Ìáò Ýöõãå ï “ÐáôÝñáò ôçò Äáíáüò”. away. We are now already post halfway through 2013 and we are Ï êïò. ÄçìÞôñçò èá ðáñáìåßíåé æùíôáíüò óôç ìíÞìç ìáò Mr. Dimitris Coustas will remain alive in our memories, still bracing ourselves for the turbulent time we are êáé êõñßùò ôùí ðáëáéïôÝñùí ðïõ åß÷áìå ôçí ôý÷ç íá ôïí especially to those of us that used to know him many years experiencing. -

FSC.EMI/48/11 13 April 2011 ENGLISH Only

FSC.EMI/48/11 13 April 2011 ENGLISH only FSC.EMI/48/11 13 April 2011 GREECE ENGLISH only Information Exchange on the Code of Conduct on Politico-Military Aspects of Security Section I: Inter- State Elements 1. Account of measures to prevent and combat terrorism. 1.1 To which agreements and arrangements (universal, regional, sub regional and bilateral) related to preventing and combating terrorism is your State a party? For prevention and suppression of terrorism, Greece follows the procedures determined by the E.U. strategy on the fight against terrorism, within the framework of work and decisions of the Council of JHA Ministers. Also, Greece participates and cooperates with the U.N., INTERPOL, EUROPOL, SIRENE National Bureau of E.U. Member States, SECI (South Eastern Cooperation Initiative), SEECP (South Eastern Cooperation Process), BSEC (Black Sea Economic Cooperation) and Adriatic-Ionian Initiative. Furthermore, for the same purpose, Greece has concluded bilateral Police Cooperation Agreements with (20) countries (EGYPT, ALBANIA, ARMENIA, BOSNIA- HERZEGOVINA, BULGARIA, ISRAEL, ITALY, CHINA, CROATIA, CYPRUS, LITHUANIA, MALTA, UKRAINE, HUNGARY, PAKISTAN, POLAND, ROMANIA, RUSSIA, SLOVENIA and TURKEY). 1.2 What national legislation has been adopted in your State to Implement the above-mentioned agreements and arrangements? Implementation of the above Agreements is always done through confirmatory Acts passed by the Greek Parliament (e.g. South Eastern Cooperation lnitiative- 2865/2000 Act, BSEC-2925/2001 Act), while further arrangements and enforcing protocols are put in force after respective Presidential Decrees, as provided by the relevant confirmatory Act (e.g. Implementation of the Decision SA 1671/2006 through the P.C. -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies. -

People on Both Sides of the Aegean Sea. Did the Achaeans And

BULLETIN OF THE MIDDLE EASTERN CULTURE CENTER IN JAPAN General Editor: H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Vol. IV 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN ESSAYS ON ANCIENT ANATOLIAN AND SYRIAN STUDIES IN THE 2ND AND IST MILLENNIUM B.C. Edited by H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN The Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan is published by Otto Harrassowitz on behalf of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan. Editorial Board General Editor: H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Associate Editors: Prof. Tsugio Mikami Prof. Masao Mori Prof. Morio Ohno Assistant Editors: Yukiya Onodera (Northwest Semitic Studies) Mutsuo Kawatoko (Islamic Studies) Sachihiro Omura (Anatolian Studies) Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Essays on Ancient Anatolian and Syrian studies in the 2nd and Ist millennium B.C. / ed. by Prince Takahito Mikasa. - Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 1991 (Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan ; Vol. 4) ISBN 3-447-03138-7 NE: Mikasa, Takahito <Prinz> [Hrsg.]; Chükintö-bunka-sentä <Tökyö>: Bulletin of the . © 1991 Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden This work, including all of its parts, is protected by Copyright. Any use beyond the limits of Copyright law without the permission of the publisher is forbidden and subject to penalty. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic Systems. Printed on acidfree paper. Manufactured by MZ-Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, 8940 Memmingen Printed in Germany ISSN 0177-1647 CONTENTS PREFACE -

Homo Digitalis' Input to the UN Special Rapporteur On

Athens, 13.05.2020 Homo Digitalis’ input to the UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, Ms. E. Tendayi Achiume, for her 2020 thematic report to the General Assembly related to Race, Borders, and Digital Technologies.1 Dear UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, Ms. E. Tendayi Achiume, Homo Digitalis is a Greek civil society organization based in Athens, Greece that focuses on the promotion and protection of human rights in the information society. We would like to thank you for your open invitation to all related stakeholders to submit their input on how digital technologies deployed in the context of border enforcement and administration reproduce, reinforce, and compound racial discrimination. With our submission we would like to provide more information about the latest developments in Greece as regards the use of digital technologies in border management activities. We have decided to focus on 3 topics, namely: • The deployment of related research projects in Greece, • The future use of facial recognition and biometric identification software in police stops by the Hellenic Police, and • The newly introduced legislation on the use of drones by the Hellenic Police in border management activities 1 This submission can be freely published on the website of the Special Rapporteur. A. The deployment of related research projects in Greece Many research projects in the field of border management are funded by the European Commission under the Horizon 2020 scheme “Secure societies - Protecting freedom and security of Europe and its citizens”.2 It is true that research projects lie at the heart of innovation and make a critical contribution to the development of Europe’s societies and cultures. -

Greece 2020 Human Rights Report

GREECE 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Greece is a constitutional republic and multiparty parliamentary democracy. Legislative authority is vested in a unicameral parliament, which approves a government headed by a prime minister. In July 2019 the country held parliamentary elections that observers considered free and fair. A government formed by the New Democracy Party headed by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis leads the country. Police are responsible for law enforcement, border security, and the maintenance of order. They are under the authority of the Ministry of Citizen Protection. The same ministry undertook responsibility for prison facilities in 2019. The Coast Guard, responsible for law and border enforcement in territorial waters, reports to the Ministry of Shipping Affairs and Island Policy. The armed forces are under the authority of the Ministry of National Defense. Police and the armed forces share law enforcement duties in certain border areas. Border protection is coordinated by a deputy minister for national defense. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the police, Coast Guard, and armed forces, and the government had effective mechanisms to investigate and punish abuse. Members of security forces committed some abuses. Significant human rights issues included: the existence of criminal libel laws; unsafe and unhealthy conditions for migrant and asylum-seeking populations detained in preremoval facilities or residing at the country’s six reception and identification centers, including gender-based violence against refugee women and children in reception facilities; allegations of refoulement of refugees; acts of corruption; violence targeting members of national/racial/ethnic minority groups, including some by police; and crimes involving violence or threats of violence targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex persons. -

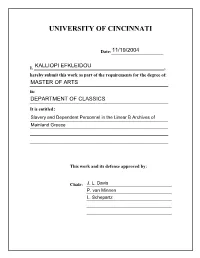

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the -

Hellenic Armed Forces Greece Has Embarked Since 2019 in an Effort to Revamp Its Armed Forces Addressing Needs That Have Remaine

Hellenic Armed Forces Greece has embarked since 2019 in an effort to revamp its armed forces addressing needs that have remained unattended for years. The first move that Athens made was the procurement of 18 Rafale fighters (12 used and 6 new) that will be delivered starting in mid-2021. Along with this it became obvious that the ships of the Hellenic Navy were showing their age, and new ships (frigates) were needed while a mid-life upgrade for the MEKO 200 frigates was also desperately needed. This is obviously the costliest of the programs being contemplated by the Hellenic Armed Forces. So far the suitors for the new frigates are: France with the digital frigates "Belh @ ra", the USA with the MMSC, Germany with four new A-200 frigates or two plus two A-200 and A-300, Dutch with the "Karel Doorman" (s.s. probably as the intermediate solution) and a possible new Onega class ships, Italy with the FREMM, and Spain with the F-110 Navantia. Germans offer for additional two type 214 submarines. Greece already has 4 type 214 submarines This in turn again brings forth the need to speed up the processes for the selection and acquisition of heavy torpedoes for the Type 214 submarines. The Navy sees this as a top pririty while the willingness to procure torpedoes is reiterated as often as possible. Both the Air Force and the Navy are looking for sub-strategic weapons to equip the new and upgraded aircraft and the new frigates. Army programs Although the interest is concentrated in the programs of the Air Force (PA) and the Navy (PN) with a focus on the acquisition of the 18 Rafale F3R as well as the four frigates, the Greek Army (ES) is also making efforts to launch armament programs. -

Doing Business in Greece

Doing Business in Greece: 2018 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2018. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. Table of Contents Doing Business in Greece ___________________________________________ 4 Market Overview ________________________________________________________ 4 Market Challenges ______________________________________________________ 7 Market Opportunities ____________________________________________________ 8 Market Entry Strategy ___________________________________________________ 8 Political and Economic Environment _________________________________ 10 Political and Economic Environment ______________________________________ 10 Selling US Products & Services _____________________________________ 11 Using an Agent to Sell US Products and Services ___________________________ 11 Establishing an Office __________________________________________________ 11 Franchising ___________________________________________________________ 12 Direct Marketing _______________________________________________________ 12 Joint Ventures/Licensing ________________________________________________ 13 Selling to the Government _______________________________________________ 13 Distribution & Sales Channels ___________________________________________ 16 Express Delivery ______________________________________________________ 17 Selling Factors & Techniques ____________________________________________ 17 eCommerce ___________________________________________________________ -

The Problem of Banditry and the Military in Nineteenth-Century Greece

Athens Journal of History - Volume 4, Issue 3 – Pages 175-196 Brigands and Brigadiers: The Problem of Banditry and the Military in Nineteenth- Century Greece By Nicholas C. J. Pappas Before the evolution of modern standing armies of Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, the recruitment and conduct of military units usually depended on their commanders. These officers were often charged by authorities to recruit, train, maintain and command a body of men in return for a lump sum or contract for a set amount of time. Formations, from company to regiment, often became proprietary, and could be purchased, inherited, and sold. The lack of employment in the military sphere would often lead these free companies and their leaders into brigandage. The establishment of effective state bureaucracies and armed forces that could pay, supply, train and discipline troops without the use of private contractors brought about the decline of free mercenary companies in Europe by the 18th century. However, irregular units under their own commanders continued in the Balkans, and in this case Greece, continued into the 20th century. Irregular forces played the predominant role in the Greek Revolution, 1821-1830, but the subsequent flawed policy of forming a regular army, in which half were foreigners, led to both an increase of banditry and to political/military turmoil. This essay is to investigate brigandage in 19th century Greece and its relationship with the mobilization, maintenance, and demobilization of the armed forces (especially irregular bands). It will also study how the irregulars were both used in irredentist movements and pursued as bandits.