Translation of Chinese Opera Proverbs from the Perspective of Intertexuality Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submitted for the Phd Degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

THE CHINESE SHORT STORY IN 1979: AN INTERPRETATION BASED ON OFFICIAL AND NONOFFICIAL LITERARY JOURNALS DESMOND A. SKEEL Submitted for the PhD degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1995 ProQuest Number: 10731694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731694 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A b s t ra c t The short story has been an important genre in 20th century Chinese literature. By its very nature the short story affords the writer the opportunity to introduce swiftly any developments in ideology, theme or style. Scholars have interpreted Chinese fiction published during 1979 as indicative of a "change" in the development of 20th century Chinese literature. This study examines a number of short stories from 1979 in order to determine the extent of that "change". The first two chapters concern the establishment of a representative database and the adoption of viable methods of interpretation. An important, although much neglected, phenomenon in the make-up of 1979 literature are the works which appeared in so-called "nonofficial" journals. -

Buddhist Text Translation Society 2012 Catalog

Sutras - Mantras - Dharma Talks - Biographical Sketches - Children’s - Audio Visual English - Chinese - Vietnamese - Spanish BUDDHIST TEXT TRANSLATION SOCIETY 2012 CATALOG BUDDHIST TEXT TRANSLATION SOCIETY (BTTS) DHARMA REALM BUDDHIST ASSOCIATION (DRBA) DHARMA REALM BUDDHIST UNIVERSITY (DRBU) www.drba.org Table of Contents Buddhist Canon 3 Water Mirror Reflecting Heaven 20 Master Hsuan Hua, Founder 3 Song of Enlightenment 20 Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 3 Exhortation to Resolve on Bodhi 20 Sutras Recitation Forty-Two Sections 4 Daily Recitation Handbook 21 Earth Store Bodhisattva 4 Evening Recitation CD 21 Medicine Master 4 Morning Recitation CD 21 Heart of the Prajna Paramita 5 Gift Books Vajra Prajna Paramita (Diamond) 5 Transcending the World 22 Buddhas Speaks of Amitabha 5 Dew Drops 22 Surangama (Shurangama) 6 Break the Shell 22 Wonderful Dharma Lotus Flower Children (Lotus) 7 Kind Monk, The 23 Flower Adornment (Avatamsaka) 8 Golden Feather, The 23 Sixth Patriarch 9 Giant Turtle, The 23 Shastra Under the Bodhi Tree 24 On Understanding No Words 24 the Hundred Dharmas 9 Human Roots 24 Mantras Standards for Students 25 Great Compassion 10 Truly Awakened One, The 25 Surangama 10 Rakshasa Ghost, The 25 Dharma Talks Spider Thread 25 Vol 1 – 11 11 Audio Trip to Taiwan 11 Clear Stream 26 In Europe 11 Amitabha Buddha 26 Insights 12 Songs for Awakening 26 Buddha Root Farm 12 Three Cart Patriarch, The 26 Listen to Yourself 13 Journals & Magazines Treasure Trove 13 Vajra Bodhi Sea 27 Ten Dharma Realms 13 Religion East & West 27 Biography/Memoirs -

Japan's Security Relations with China Since 1989

Japan’s Security Relations with China since 1989 The Japanese–Chinese security relationship is one of the most important vari- ables in the formation of a new strategic environment in the Asia-Pacific region which has not only regional but also global implications. The book investigates how and why since the 1990s China has turned in the Japanese perception from a benign neighbour to an ominous challenge, with implications not only for Japan’s security, but also its economy, role in Asia and identity as the first devel- oped Asian nation. Japan’s reaction to this challenge has been a policy of engagement, which consists of political and economic enmeshment of China, hedged by political and military power balancing. The unique approach of this book is the use of an extended security concept to analyse this policy, which allows a better and more systematic understanding of its many inherent contradictions and conflicting dynamics, including the centrifugal forces arising from the Japan–China–US triangular relationship. Many contradictions of Japan’s engagement policy arise from the overlap of military and political power-balancing tools which are part of containment as well as of engagement, a reality which is downplayed by Japan but not ignored by China. The complex nature of engagement explains the recent reinforcement of Japan’s security cooperation with the US and Tokyo’s efforts to increase the security dialogues with countries neighbouring China, such as Vietnam, Myanmar and the five Central Asian countries. The book raises the crucial question of whether Japan’s political leadership, which is still preoccupied with finding a new political constellation and with overcoming a deep economic crisis, is able to handle such a complex policy in the face of an increasingly assertive China and a US alliance partner with strong swings between engaging and containing China’s power. -

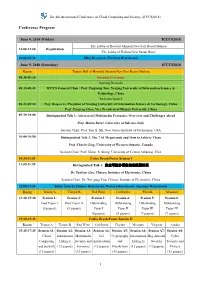

Conference Program

The 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Security (ICCCS2018) Conference Program June 8, 2018 (Friday) ICCCS2018 The Lobby of Howard Johnson New Port Resort Haikou 14:00-21:00 Registration The Lobby of Haikou New Yantai Hotel 18:00-21:30 BBQ Reception (Western Restaurant) June 9, 2018 (Saturday) ICCCS2018 Room Tianjin Hall of Howard Johnson New Port Resort Haikou 08:30-09:10 Opening Ceremony Opening Remarks 08:35-08:45 ICCCS General Chair: Prof. Xingming Sun, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China Welcome Speech 08:45-09:10 Prof. Beiqun Li, President of Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China Prof. Xianfeng Chen, Vice President of Hainan University, China 09:10-10:00 Distinguished Talk 1: Adversarial Multimedia Forensics: Overview and Challenges Ahead Prof. Mauro Barni, University of Salerno, Italy Session Chair: Prof. Yun Q. Shi, New Jersey Institute of Technolgoy, USA 10:00-10:50 Distinguished Talk 2: The 7 AI Megatrends and How to Achieve Them Prof. Charles Ling, University of Western Ontario, Canada Session Chair: Prof. Victor. S. Sheng, University of Central Arkansas, USA 10:50-11:05 Coffee Break/Poster Session I 11:05-11:55 Distinguished Talk 3: 安全可控多模态信息隐藏体系 Dr. Yunbiao Guo, Chinese Institute of Electronics, China Session Chair: Dr. Xin’gang You, Chinese Institute of Electronics, China 12:00-13:30 Buffet Lunch (Chinese Restaurant, Western Restaurant, Japanese Restaurant) Room Tianjin A Tianjin B Red Wine California Florida Missouri 13:30-15:30 Session 1: Session 2: Session -

The Yangguanzhai Neolithic Archaeological Project

THE YANGGUANZHAI NEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, CHINA Course ID: ARCH 380A June 14 -July 18, 2020 Academic Credits: 8 Semester Credit Units (Equivalent to 12 Quarter Units) School of Record: Connecticut College PROJECT DIRECTORS: Dr. Richard Ehrich, Northwest University (China) and UCLA ([email protected]) Dr. Zhouyong Sun, Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, China ([email protected]) Mr. Yang Liping, Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, China ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION The prehistoric village of Yangguanzhai (YGZ) dates to the Middle to Late Yangshao period (c. 3,500 - 3,000 BCE). It is one of the largest settlements of its kind. The site is located in the Jing River Valley, approximately 25 kilometers north of the ancient city of Xi’an in northwest China. Since 2004, in preparation for a major construction project, the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology began to conduct large-scale excavations and exploratory surveys – by means of test trenches and coring with the Luoyang spade – in various parts of the site. More than 18,000 square meters have been excavated to date. These activities revealed a moat, a row of cave dwellings, subterranean houses, child urn burials in the residential areas, and numerous pottery kilns. The quantity and quality of finds were impressive enough for the Chinese authorities to halt commercial development and declare the area a protected archaeological site. In 2010, as part of the ongoing excavation, a joint UCLA/Shaanxi Province Archaeological Academy/Xibei University project began to operate at the site. This project is shifting the focus from the large-scale exposure of architecture to a more careful and systematic analysis of local stratigraphy and a stronger 1 | P a g e emphasis on anthropological interpretations. -

Disciplining of a Society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China

Disciplining of a Society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China Thomas Heberer August 2020 Disciplining of a Society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China Thomas Heberer August 2020 disciplining of a society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China about the author Thomas Heberer is Senior Professor of Chinese Politics and Society at the Insti- tute of Political Science and the Institute of East Asian Studies at the University Duisburg-Essen in Germany. He is specializing on issues such as political, social and institutional change, entrepreneurship, strategic groups, the Chinese developmen- tal state, urban and rural development, political representation, corruption, ethnic minorities and nationalities’ policies, the role of intellectual ideas in politics, field- work methodology, and political culture. Heberer is conducting fieldwork in China on almost an annual basis since 1981. He recently published the book “Weapons of the Rich. Strategic Action of Private Entrepreneurs in Contemporary China” (Singapore, London, New York: World Scientific 2020, co-authored by G. Schubert). On details of his academic oeuvre, research projects and publications see his website: ht tp:// uni-due.de/oapol/. iii disciplining of a society Social Disciplining and Civilizing Processes in Contemporary China about the ash center The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, edu- cation, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing power- ful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. -

The University of Chicago Manchurian Atlas

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MANCHURIAN ATLAS: COMPETITIVE GEOPOLITICS, PLANNED INDUSTRIALIZATION, AND THE RISE OF HEAVY INDUSTRIAL STATE IN NORTHEAST CHINA, 1918-1954 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY HAI ZHAO CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2015 For My Parents, Zhao Huisheng and Li Hong ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It has been an odyssey for me. The University of Chicago has become both a source of my intellectual curiosity and a ladder I had to overcome. Fortunately, I have always enjoyed great help and support throughout the challenging journey. I cannot express enough thanks to my academic advisors—Professor Bruce Cumings, Professor Prasenjit Duara, and Professor Guy Alitto—for their dedicated teaching, inspiring guidance and continued encouragement. I have also benefited immensely, during various stages of my dissertation, from the discussions with and comments from Professor Salim Yaqub, Professor James Hevia, Professor Kenneth Pomeranz, and Professor Jacob Eyferth. Professor Dali Yang of Political Sciences and Professor Dingxin Zhao of Sociology provided valuable insights and critiques after my presentation at the East Asia Workshop. My sincere thanks also goes to Professor Shen Zhihua at the East China Normal University who initiated my historical inquiry. I am deeply indebted to my friends and colleagues without whom it would not have been possible to complete this work: Stephen Halsey, Paul Mariani, Grace Chae, Suzy Wang, Scott Relyea, Limin Teh, Nianshen Song, Covell Meyskens, Ling Zhang, Taeju Kim, Chengpang Lee, Guo Quan Seng, Geng Tian, Yang Zhang, and Noriko Yamaguchi. -

Civil-Military Change in China: Elites, Institutes, and Ideas After the 16Th Party Congress

CIVIL-MILITARY CHANGE IN CHINA: ELITES, INSTITUTES, AND IDEAS AFTER THE 16TH PARTY CONGRESS Edited by Andrew Scobell Larry Wortzel September 2004 Visit our website for other free publication downloads Strategic Studies Institute Home To rate this publication click here. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or by e-mail at [email protected] ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/ ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-165-2 ii CONTENTS Foreword Ambassador James R. Lilley ............................................................................ v 1. Introduction Andrew Scobell and Larry Wortzel ................................................................ -

The Role of China in Korean Unification

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2003-06 The role of China in Korean unification Son, Dae Yeol Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/905 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE ROLE OF CHINA IN KOREAN UNIFICATION by Dae Yeol Son June 2003 Thesis Advisor: Edward A. Olsen Second Reader: Gaye Christoffersen Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2003 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: The Role of China in Korean Unification 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHOR(S) : Dae Yeol Son 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. -

Survey of China's Economic Contract Law, A

A SURVEY OF CHINA'S ECONOMIC CONTRACT LAW Guiguo Wang* I. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Since the adoption of the Economic Contract Law of the Peo- ple's Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as the "Contract Law") on December 13, 1981,1 there has been enthusiasm and curi- osity regarding its implementation and its impact on China's legal and economic systems. Owing to the fact that the Contract Law has been in force for less than four years, very few cases have been decided under it, and very little commentary has been available about it outside China. This article will summarize the Chinese practice in enforcement of contracts, analyze the basic features of the Contract Law, compare its provisions with Chinese customs, and outline its impact on Chinese society. Even during the imperial period, when no officially promul- gated contract law existed, the Chinese government recognized con- tracts entered into by its people. The case of Chen Minsheng and Lu Siyi,2 decided by District Magistrate Yu Chenglong early in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911 A.D.) illustrates this point. The facts of the case are as follows: Lu's grandfather took a loan from Chen's grandfather in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 A.D.). Several years after the loan was made, the Manchus overthrew the Ming and es- * J.S.D., Yale University; LL.M., Columbia University. This article was written while the author was visiting at Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, Los Angeles, Cali- fornia. The author has served in the Department of Law and Treaties of the Foreign Ministry of the People's Republic of China (1979-80). -

The Literary Field of Twentieth-Century China Chinese Worlds

The Literary Field of Twentieth-Century China Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders - overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South-East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social-science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Army Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N. Pieke and Hein Mallee Alexander -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 356 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Ecological Studies (CESSES 2019) The Discovery, Adaption and Memory of Feng Zhiqin's Story An Example of Marital Autonomy Wenpan Zuo School of Marxism Northwest Normal University Lanzhou, China 730070 Abstract—"Fangzhiqin Marital Dispute Case" is an ordinary Especially the heroine Feng Zhiqin in the case2, she became civil case that occurred in the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Border the creative prototype of the artistic role of "Liu Qiaoer" after Region in the 1940s. The case was reported by the press, and its the report from news media, and then through the creation, protagonist Feng Zhiqin became the prototype of the artistic role performance and dissemination of the literary and art circles - of "Liu Qiaoer". After the adaption of literary and art circles, the Shanxi Opera "Liu Qiaoer's lawsuit" and the storytelling Liu Qiaoer was portrayed as a model of women's "resistance to "Reunion of Liu Qiaoer " staged in the border area in the feudal mercenary marriage, and fight for marital autonomy", 1940s ,and Pingju "Liu Qiaoer" and the film "Liu Qiaoer" and spread widely until today. Although there is a certain gap staged after the founding of PRC , have made the story of Liu between the content of this story and the historical facts, it does Qiaoer be known to every household. She was portrayed as a not affect the artistry of the literary and artistic works and the typical image of Chinese women "resisting in feudal appreciation of the people, thus serves for official discourse.