Neues Museum Nürnberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

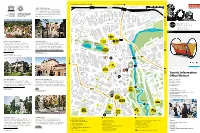

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Museums Castles Gardens the Weimar Cosmos

Opening Times and Prices TOURS Winter Summer Adults Reduced Pupils Goethe National Museum Museums and historical sites MTWTFSS starts on last starts on last 16 – 20 years Tour 1: A Sunday in October Sunday in March Goethe and Classical Weimar with the Goethe Residence MUSEUMS Bauhaus-Museum Weimar* 10.00 am – 2.30 pm 10.00 am – 2.30 pm € 11.00 € 7.00 € 3.50 5 min. Goethe National Museum, Wittumspalais, 10.00 am – 6.00 pm 10.00 am – 6.00 pm € 11.00 € 7.00 € 3.50 Park on the Ilm and the Goethe Gartenhaus B Wittumspalais Ducal Vault 10.00 am – 4.00 pm 10.00 am – 6.00 pm € 4.50 € 3.50 € 1.50 All year round CASTLES Duration: 5 hours, distance: ca. 1,5 km Goethe Gartenhaus 10.00 am – 4.00 pm 10.00 am – 6.00 pm € 6.50 € 5.00 € 2.50 8 min. Cost: Price of admission to the respective museums Tip: Goethe National Museum 9.30 am – 4.00 pm 9.30 am – 6.00 pm € 12.50 € 9.00 € 4.00 Park on 10 min. Goethe- und The exhibition “Flood of Life – Storm of Deeds” reveals how C GARDENS Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv 8.30 am – 6.00 pm 8.30 am – 6.00 pm free modern Goethe’s ideas still are today. We recommend planning the Ilm Schiller-Archiv Opening times vary at the following at least two hours for your visit to the Goethe Residence where weekends: 12/13 Jan; 13/14 Apr; 11.00 am – 6.00 pm 10.00 am – 4.00 pm free 8 min. -

Bauhaus Centenary Year May Be Over, but the Influential Art and Design Movement Remains in the International Spotlight

Dear Journalist/Editor The Bauhaus centenary year may be over, but the influential art and design movement remains in the international spotlight. Below is an article that in- cludes comments from eminent publications, pointing out that 2019 was a cat- alyst for a new appreciation of the Bauhaus movement. And that interest con- tinues in 2020. Inspired by exhibitions both in Germany and around the world, more and more visitors are planning vacations in BauhausLand, the German federal states of Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. This editorial contribution is, of course, free for use. Bauhaus: Still in the spotlight! BAUHAUSLAND: ATTRACTING NEW FANS In 2019, the worldwide celebrations for the centenary of the Bauhaus focused on the achievements of this influential art and design movement. The range of exhibitions appealed to aficionados, but they also attracted a brand-new audi- ence. Leila Stone wrote in The Architect’s Newspaper: “Bauhaus is architec- ture. Bauhaus is costume design. Bauhaus is textile design. Bauhaus is furni- ture…it has never been more clear that Bauhaus is everywhere.” With appre- ciation increasing, more and more fans are planning to visit BauhausLand www.gobauhaus.com to spend their 2020 vacations in the German federal states of Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. BAUHAUSLAND: THE HOT DESTINATION FOR 2020 GQ Magazine trumpeted the headline: “Why travel trendsetters are heading for the birthplace of Bauhaus.” The list of ‘must dos’ includes the striking new Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, where the ‘must sees’ range from Josef Albers’ ground-breaking Nesting Tables to Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s Glass Table Lamp, which is still manufactured today! As for Architectural Digest, it names the brand-new Bauhaus Museum Dessau as one of its “Top 20 Places to Travel in 2020,” adding that “If you decide to go on a Bauhaus-themed pilgrimage, be sure to visit the Meisterhäuser, a group of white cubist homes where Gropius, Kandinsky, and other Bauhaus luminaries lived.” TourComm Germany Olbrichtstr. -

Nicolai-Press-Releas

CAROLINA NITSCH OLAF NICOLAI Z. POINT October 3 – November 16, 2013 At Carolina Nitsch Project Room Opening and book signing October 3, 6-8 pm Carolina Nitsch is pleased to present Olaf Nicolai’s second solo exhibition with the gallery entitled Z. Point, which consists of 80 photographs, a floor installation and an artist’s book. Z. Point originated with the artist’s 2008 visit to Zabriskie Point in Death Valley, California, a site known for unusually striking geological formations as well as the eponymous film by Michelangelo Antonioni. The location was packed with tourists during the day who were primarily interested the geological significance and may never have heard of Antonioni. In order to explore the area alone Nicolai needed to go there at night. Because of the intense darkness, he used the camera flash on his cell phone to guide his path. As an unintentional result, 80 photographs were taken, documenting this exploration. These images now line the gallery walls in the same order they were taken so that the viewer can also traverse the same path as the artist. Nicolai’s installation presents the viewer with a counter point by exploring this landscape at night as opposed to Antonioni’s bright, sexually powered work. By using the flash at night to capture the landscape, while the sun is on the other side of the planet, Nicolai removes the grandeur of the place and replaces it with a curious sort of longing or searching, as if waiting for life to happen. While "wandering" around in the gallery space and watching the photographed landscape, visitors are in fact moving through another landscape, which is formed by the second piece in the show. -

New Approaches Toward Recent Gay Chicano Authors and Their Audience

Selling a Feeling: New Approaches Toward Recent Gay Chicano Authors and Their Audience Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Douglas Paul William Bush, M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Ignacio Corona, Advisor Frederick Luis Aldama Fernando Unzueta Copyright by Douglas Paul William Bush 2013 Abstract Gay Chicano authors have been criticized for not forming the same type of strong literary identity and community as their Chicana feminist counterparts, a counterpublic that has given voice not only to themselves as authors, but also to countless readers who see themselves reflected in their texts. One of the strengths of the Chicana feminist movement is that they have not only produced their own works, but have made sense of them as well, creating a female-to-female tradition that was previously lacking. Instead of merely reiterating that gay Chicano authors have not formed this community and common identity, this dissertation instead turns the conversation toward the reader. Specifically, I move from how authors make sense of their texts and form community, to how readers may make sense of texts, and finally, to how readers form community. I limit this conversation to three authors in particular—Alex Espinoza, Rigoberto González, and Manuel Muñoz— whom I label the second generation of gay Chicano writers. In González, I combine the cognitive study of empathy and sympathy to examine how he constructs affective planes that pull the reader into feeling for and with the characters that he draws. -

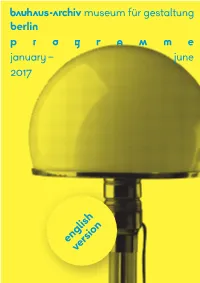

English Version January – June 7

berli� p�������e january – june ���7 english version editorial dear visitors, the Bauhaus-Archiv is setting things in motion! Our plans for expanding the museum are becoming increasingly concrete: in March of ���8 we will be leaving our existing building for two years, in order to subsequently return to the modernised museum building and the new annex, with its generously proportioned exhibition spaces. We are already beginning with the preparations. The library and archive will thus be closed from � January ���7. Our major retrospective Jasper Morrison. Thingness deals with the work of one of the best-known contemporary designers: when it opens on �� March ���7, we will begin preparing our exhibition objects for the move. The most impor- tant objects and documents related to the Bauhaus and its history will continue to be shown in the special exhibition Bauhaus in Motion, which will start on � March ���7. Join me in looking forward to the coming changes! We wish you a wonderful time at the Bauhaus-Archiv. Annemarie Jaeggi The Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung Director researches and presents the history and influence of the Bauhaus, which operated from 1919 to 1933 in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin, and was among the 20th century’s most important schools of architecture, design and art. The Bauhaus-Archiv was initiated in 1960 by the art historian Hans Maria Wingler – with the support of the Bauhaus’s founder, Walter Gropius – for the purpose of providing a new home for the material legacy of the Bauhaus, which was scattered around the world in 1933. In 1979, after multiple relocations, the Bauhaus- Archiv was finally able to move into the building in Berlin that Gropius designed for it. -

Antonia Hirsch * Frankfurt Am Main, Germany

Antonia Hirsch * Frankfurt am Main, Germany EDUCATION 1991–94 • BA Fine Art, Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design, London, GB 1990–91 • Foundation Studies, London Metropolitan University, GB SELECTED AWARDS / RESIDENCIES • Freies Reisestipendium (Japan), Hessische Kulturstiftung, DE, 2022 • Research and Creation Grant, Canada Council for the Arts, 2020–21 • Arbeitsstipendium, Stiftung Kunstfonds, DE, 2020 • Travel Allowance for Work Abroad. Berlin Senate, DE, 2020 • Residency. CCA Andratx, ES, 2013 • Research and Development Grant. Canada Council for the Arts, 2017–19 • Visual Arts Grant. Canada Council for the Arts, 1997, 2005, 2009, 2011, 2015 • Residency. Or Gallery Berlin, DE, 2012 • Art Book of the Moment Award, Art Gallery of York University, CA, 2011 • Residency. Program, Berlin, DE, 2008–09 • Visual Arts Individual Award. British Columbia Arts Council, 2000, 2004, 2007, 2009 • Travel Grant. Canada Council for the Arts, 1999, 2003, 2004, 2006 • Residency. Cité internationale des arts / Canada Council. Paris, FR, 2004 • Media Arts Production Grant. Canada Council for the Arts, 2001 • Media Arts Creative Development Grant. Canada Council for the Arts 1999 • Visual Arts Development Award. Vancouver Foundation, CA, 1998 • Residency/Full Scholarship. Banff Centre for the Arts, CA, 1998 SELECTED PUBLIC COLLECTIONS • National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, CA • Vancouver Art Gallery, CA • Surrey Art Gallery, CA • Art Bank, Ottawa, CA • Kunstbibliothek der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, DE • National Art Library at the V&A, London, -

Konferenz Bauhuas Sammel Pr

Bauhaus Dessau : Conference Collecting Bauhaus 2.+3.+4.+5.12. 20191 2 1 + Provenances: Case Studies + Contiguities: + + + The Museum as Context of Com mu ni- cation + + + Methods: Visibility of the Global For the centenary of the Bauhaus three have tried, by way of a synthesis of global new Bauhaus museums will open their perspectives, to move away from restrictive, doors to the public in Germany. The muse- nationally based ideas of identity. The Bau- ums in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin are haus Dessau Foundation too subscribes to connected to the transnational history of this new approach to historiography. Bauhaus exhibits that has grown over one hundred years of global acquisition and The conference Collecting Bauhaus collection. For the canonical representation brings together international experts from of modern art and design in the twentieth public and private institutions with Bauhaus century the Bauhaus is a constant. Pro- collections. The aim is to discuss the global- duced in the brief but enormously produc- ly dispersed objects and collection histories tive period between 1919 and 1933, the of the Bauhaus, revisit exhibition and com- work of the Bauhaus is inextricably linked munication strategies and consider how to its dramatic history in the twentieth cen- museumsinthetwenty-firstcenturymight tury, from closure to expulsion and exile. benefitfromtheseglobalinterconnections. The initial idea for the conference concept From its inception, the Bauhaus served as was developed by Regina Bittner. The con- an international platform for a wide-ranging ference focus on the provenance, relocation European and international avant-garde and changing ownership of Bauhaus ob- movement in architecture, art and design. -

2Nd International Symposium Art Commissions Art in Public Spaces Programme

2nd International Symposium Art Commissions Art in Public Spaces Programme Tuesday 27 November 2018, Deutsche Bank, Berlin 14:00 – 16:30 Programme Afternoon session Contemporary Visions and Practice Deutsche Bank, Friedrich-Saal, Charlottenstraße 37, Speaker: Olaf Nicolai 10117 Berlin, Germany Artist, Berlin, Germany Speaker: Dorothea Strauss Head of Corporate Social Responsibility 09:00 – 09:45 “La Mobilière”, Bern, Switzerland – IACCCA Member Registration and cofee 09:45 – 10:00 Speaker: Superflex with Jakob Fenger Welcoming and opening Artists, Copenhagen, Denmark Loa Haagen Pictet 15:15 – 15:30 Chief Curator of Collection Pictet, Geneva, Cofee break Switzerland – IACCCA Chair Speaker: Ooze Architects & Marjetica Potrč with Sylvain Hartenberg, Eva Pfannes & Marjetica Potrč Jane Morris, moderator Architects, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Editor-at-large of The Art Newspaper, Artist, Berlin, Germany London/New York, UK/USA Debate/Discussion 10:00 – 12:30 Morning session 16:30 – 16:45 The Role of Art in Public Spaces Closing remarks by Delphine Munro Head of Arts & Culture, European Investment Bank, Luxembourg — IACCCA Board Member Speaker: Kasper König Curator, Berlin, Germany 16:45 – 17:00 Speaker: Cristina Iglesias Speech and invitation to visit PalaisPopulaire Artist, Madrid, Spain by Friedhelm Hütte Global Head of Deutsche Bank Art Speaker: Sandra Bloodworth Art, Culture & Sports, Frankfurt, Germany Director, MTA Arts & Design, Metropolitan Transportation Authority New York, USA Debate/Discussion 17:30 – 20:00 Drinks reception & visit of the exhibition 12:30–14:00 The World on Paper Networking lunch at Friedrich-Saal at the PalaisPopulaire About IACCCA Created in 2007, the International Association of Corporate Collections of Contemporary Art (IACCCA) is a non-profit association of corporate curators from around the world. -

Weimar. Recherchetipps

Recherchetipps Ideen für Ihre Recherche zu Weimar Thüringer Tourismus GmbH · Willy-Brandt-Platz 1 · 99084 Erfurt Fax 0361 3742-299 · http://presse.thueringen-entdecken.de Mandy Neumann: Tel. 0361 3742-219 · [email protected] Theresa Wolff: Tel. 0361 3742-240 · [email protected] Weimar. Recherchetipps In Weimar, der Kulturstadt Europas 1999, waren viele große Persönlichkeiten zu Hause: Goethe, Schiller, Herder, Bach, Liszt, Wieland, Cranach, van de Velde oder Gropius, der Begründer des Bauhauses. Zahlreiche Museen und Gedenkstätten in Weimar erinnern an diese Namen und künden vom Ruhm vergangener Zeiten. Noch heute ist die Stadt ein Zentrum von Kunst und Kultur. Seit Generationen lockt Weimar mit dem berühmten Bronzedenkmal von Goethe und Schiller vor dem Deutschen Nationaltheater und Museen und Ausstellungen Gäste aus aller Welt an. Imagefilm: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7CDBvcCB06I Sehenswertes & Besonderes Weimar ist mehr als die Stadt der Klassiker oder des Bauhauses. Im Laufe mehrerer Jahrhunderte haben sich immer wieder bedeutsame Dichter, Denker und Künstler in der Kulturstadt versammelt. Bis heute können die authentischen Schauplätze in der UNESCO-Welterbestadt bestaunt werden. 14 einzigartige Objekte, der insgesamt 27 Museen, Schlösser und Parks sind auf der Welterbeliste der UNESCO gelistet. Die Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, der Park an der Ilm, das Goethe Nationalmuseum mit dem Wohnhaus oder das neue Bauhaus-Museum Weimar sind nur einige der zahlreichen Sehenswürdigkeiten Weimars. Neue Natur Unter der Überschrift „Neue Natur“ widmet sich die Klassik Stiftung Weimar 2021 mit einem kompletten Themenjahr dem Verhältnis von Mensch und Natur. Zahlreiche Ausstellungen, Feste, Podiumsdiskussionen und Workshops an verschiedenen Orten in der Stadt flankieren das Thema, das Hauptaugenmerk gilt jedoch den Parks selbst. -

100 Years of Bauhaus

Excursions to the Visit the Sites of the Bauhaus Sites of and the Bauhaus Modernism A travel planner and Modernism! ↘ bauhaus100.de/en # bauhaus100 The UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the Sites of Bauhaus Modernism Hamburg P. 31 Celle Bernau P. 17 P. 29 Potsdam Berlin P. 13 Caputh P. 17 P. 17 Alfeld Luckenwalde Goslar Wittenberg P. 29 P. 17 Dessau P. 29 P. 10 Quedlinburg P. 10 Essen P. 10 P. 27 Krefeld Leipzig P. 27 P. 19 Düsseldorf Löbau Zwenkau Weimar P. 19 P. 27 Dornburg Dresden P. 19 Gera P. 19 P. 7 P. 7 P. 7 Künzell P. 23 Frankfurt P. 23 Kindenheim P. 25 Ludwigshafen P. 25 Völklingen P. 25 Karlsruhe Stuttgart P. 21 P. 21 Ulm P. 21 Bauhaus institutions that maintain collections Modernist UNESCO World Heritage Sites Additional modernist sites 3 100 years of bauhaus The Bauhaus: an idea that has really caught on. Not just in Germany, but also worldwide. Functional design and modern construction have shaped an era. The dream of a Gesamtkunst- werk—a total work of art that synthesises fine and applied art, architecture and design, dance and theatre—continues to this day to provide impulses for our cultural creation and our living environments. The year 2019 marks the 100 th anniversary of the celebration, but the allure of an idea that transcends founding of the Bauhaus. Established in Weimar both time and borders. The centenary year is being in 1919, relocated to Dessau in 1925 and closed in marked by an extensive programme with a multitude Berlin under pressure from the National Socialists in of exhibitions and events about architecture 1933, the Bauhaus existed for only 14 years. -

Amazon: Vom Online-Buchhändler Zum Städtebauer

546 Das Querformat für Architekten 21. November 2019 MANIFESTA REVISITED AMAZON Ausstellung in Amsterdam VOM ONLINE-BUCHHÄNDLER ZUM STÄDTEBAUER 546 DIESE WOCHE Amazon ist längst viel mehr als ein Onlinehändler. Mit neuen Ladenkonzepten erobert das Unter- nehmen die Städte, durch seine Niederlassungen verändert es ganze Nachbarschaften – und provo- ziert mitunter heftige Proteste. Stadtverwaltungen und BewohnerInnen suchen nach Wegen, um auf den neuen Stadtakteur zu reagieren. 3 Architekturwoche 6 Amazon: Vom Online-Buchhändler zum Städtebauer 4 News Von Felix Hartenstein 2 19 Bild der Woche Titel: Amazon Seattle Headquarters, Sphere 1. Foto: Amazon oben: Amazons erstes Bürogebäude in Seattle. Foto: flickr / hescibl Heinze GmbH | NL Berlin | BauNetz Architekturwoche News Dossier Bild der Woche der Bild Dossier Architekturwoche News Geschäftsführer: Dirk Schöning Gesamtleitung: Stephan Westermann Inhalt Chefredaktion: Friederike Meyer Keine Ausgabe verpassen mit Redaktion dieser Ausgabe: Friederike Meyer, Stephan Becker dem Baunetzwoche-Newsletter. Artdirektion: Natascha Schuler Jetzt abonnieren! 546 MONTAG 3 Es klingt fast wie Satire: Mit Airbnb und dem IOC verkündeten am Montag zwei News Dossier Bild der Woche der Bild Dossier News im städtischen Raum eher unliebsame Akteure eine strategische Partnerschaft. Droht Olympia-Standorten nicht eh der Ausverkauf, und lässt Airbnb nicht von ganz allein die Mieten steigen? Begründet wird das Ganze noch dazu mit einem Nachhaltigkeitsansatz, der weniger sinnlose Bauaktivität und mehr Geld für die Einheimischen verspricht. Zynismus pur könnte man angesichts vieler negativer Airbnb-Konsequenzen meinen. Anne Hidalgo, Bürgermeisterin von Paris, wo die Spiele 2024 stattfinden, ist jedenfalls nicht amüsiert. Gerade erst hatte ihre Verwal- Architekturwoche Airbnb-Mitgründer Joe Gebbia und IOC-Präsident Thomas sb Bach, Foto: Matt Alexander PA Wire / IOC / CC BY-NC- tung gegen den US-Konzern und seine mangelnde Transparenz geklagt.