Responses of Seabirds to the Rabbit Eradication on Ile Verte, Sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Archipelago S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Record of a Broad-Billed Prion Pachyptila Vittata at Coronation Island, South Orkney Islands

Blight & Woehler: First record of a Broad-billed Prion at Coronation Island 191 FIRST RECORD OF A BROAD-BILLED PRION PACHYPTILA VITTATA AT CORONATION ISLAND, SOUTH ORKNEY ISLANDS LOUISE K. BLIGHT1,2 & ERIC J. WOEHLER3 1Procellaria Research and Consulting, 944 Dunsmuir Road, Victoria, British Columbia, V9A 5C3, Canada 2Current address: Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z4, Canada ([email protected]) 3School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, 7005, Australia Received 15 April 2008, accepted 2 August 2008 The known breeding distribution of Broad-billed Prions Pachyptila or as a bird blown out of its normal at-sea range by strong winds vittata is restricted to Tristan da Cunha and Gough Islands in the during poor weather. Alternatively, there may be low numbers of South Atlantic Ocean and to offshore islands around New Zealand Broad-billed Prions breeding at poorly-surveyed sub-Antarctic and the Snares and Chatham Islands, with the range at sea believed colonies, such as the South Orkney Islands. Antarctic Prions are one to extend to coastal South Africa in the South Atlantic Ocean and of the most numerous seabird species in the Antarctic (Marchant & near-shore waters around New Zealand (Marchant & Higgins 1990). Higgins 1990); they nest in the South Orkney Islands (Marchant & The taxonomy of prions remains controversial, with most authors Higgins 1990). It is possible that low numbers of breeding Broad- recognising up to six species, but varying numbers of subspecies. billed Prions have been overlooked amongst their congeners. The at-sea ranges of many Southern Ocean seabird species are Although no sympatric breeding sites are known for the two species still incompletely described, with relatively few surveys obtaining (Shirihai 2002) and the presence of this bird may have been an at-sea data for prions. -

Birdlife Australia Rarities Committee Unusual Record Report Form

BirdLife Australia Rarities Committee Unusual Record Report Form This form is intended to aid observers in the preparation of a submission for a major rarity in Australia. (It is not a mandatory requirement) Please complete all sections ensuring that you attach all relevant information including any digital images (email to [email protected] or [email protected]). Submissions to BARC should be submitted electronically wherever possible. Full Name: Rob Morris Office Use Address: Phone No: Robert P. Morris, Email: Full Name: Andrew Sutherland (first noticed the second bird) Address: Phone No: Email: Species Name: Broad-billed Prion Scientific Name: Pachyptila vittata Date(s) and time(s) of observation: 11 August 2019 First individual photographed at 12.22 – last bird photographed at 13.11. How long did you watch the bird(s)? c30+ minutes – multiple sightings of 2 birds (possibly 3) and then an additional sighting of 1 bird 20 minutes later whilst travelling, flying past and photographed. First and last date of occurrence: 11 August 2019 Distance to bird: Down to approximately 20-30 m Site Location: SE Tasmania. Approximately 42°50'36.30"S 148°24'46.23"E 22NM ENE of Pirates Bay, Eaglehawk Neck. We went north in an attempt to seek lighter winds and less swell and avoid heading straight into the strong SE winds and southerly swell. Habitat (describe habitat in which the bird was seen): Continental slope waters at a depth of approximately 260 fathoms. Sighting conditions (weather, visibility, light conditions etc.): Weather: Both days were mostly cloudy with occasional periods of bright sunshine. -

DIET and ASPECTS of FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING at SOUTH GEORGIA by P.A

DIET AND ASPECTS OF FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING AT SOUTH GEORGIA By P.A. PRINCE AND P.G. COPESTAKE ABSTRACT A subantarctic population of the Fairy Prion (Pachyprzla turtur) was studied at South Georgia in 1982-83. Full measurements of breeding birds are given, together with details of breeding habitat, the timing of the main breeding cycle events, and chick growth (weight and wing, culmen and tarsus length). Regurgitated food samples showed the diet to be mainly Crustacea (96% by weight), fish and squid comprising the rest. Of crustaceans, Antarctic krill made up 38% of items and 80% by weight. Copepods (four species, mostly Rhincalanus gigas) made up 39% of items but only 4% by weight; amphipods [three species, principally Themisto gaudichaudii made up 22% of items and 16% by weight. Diet and frequency of chick feeding are compared with those of Antarctic Prions and Blue Petrels at the same site; Fairy Prions are essentially intermediate. INTRODUCTION The Fairy Prion (Pachyptila turtur) is one of six members of a genus confined to the temperate and subantarctic regions of the Southern Hemisphere. With the Fulmar Prion (P. crassirostris), it forms the subgenus Pseudoprion. Its main area of breeding distribution is between the Antarctic Polar Front and the Subtropical Convergence. It is widespread in the New Zealand region, from the north of the North Island south to the Antipodes Islands and Macquarie Island, where only about 40 pairs survive (Brothers 1984). Although widespread in the Indian Ocean at the Prince Edward, Crozet and Kerguelen Islands, in the South Atlantic Ocean it is known to breed only on Beauchene Island (Falkland Islands) (Strange 1968, Smith & Prince 1985) and South Georgia (Prince & Croxall 1983). -

Salvin's Prion Pachyptila Salvini Captured Alive on Beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27Th July 1974

1 Salvin’s Prion Pachyptila salvini captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27th July 1974 by Mike Carter Fig. 1. Ailing Salvin’s Prion captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27 July 1974 During a gale on 27th July 1974, a Salvin’s Prion was observed flying over the breakers just beyond the rocks on the beach at Black Rocks, Victoria. Obviously debilitated, it came ashore and sought refuge in rock pools. It was rescued but died within five hours. This observation was made by a group of local and international seabird enthusiasts that included Dr Bill Bourne (from the UK), Gavin Johnstone & Noels Kerry from the Australian Antarctic Division, Peter Menkhorst, Richard Loyn, Paul Chick and me. Overseas and interstate visitors had joined locals to attend an International Ornithological Congress in Melbourne. The attached photos are recent digital copies of transparencies taken immediately after capture. Dimensions in mm measured as described in Marchant & Higgins (1990) on 29-07-74. (L = left, R = right), Wing 191; Tail 94; Tarsus (L) 36.4, (R) 35.9; Middle toe (L) 45.2, (R) 45.7; Claw (L) 8.8, (R) 8.0. Culmen (C) 31.8; Width (W) 16.4; Ratio (C)/ (W) 1.94: Bill depth max 13.2; Bill depth min 7.2. Apparent bulk = 1/4CW(BDmax+BDmin) = 2661 cub mm. I find this generated number to be a good discriminator for identifying Victorian prion corpses. 2 Figs. 2 to 5. Ailing Salvin’s Prion captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27 July 1974 Identification Identification at the time was based mainly on information in Serventy, Serventy & Warham (1971). -

Olfactory Foraging by Antarctic Procellariiform Seabirds: Life at High Reynolds Numbers

Reference: Biol. Bull. 198: 245–253. (April 2000) Olfactory Foraging by Antarctic Procellariiform Seabirds: Life at High Reynolds Numbers GABRIELLE A. NEVITT Section of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, University of California, Davis, California 95616 Abstract. Antarctic procellariiform seabirds forage over (Chelonia mydas) nesting on Ascension Island in the middle vast stretches of open ocean in search of patchily distributed of the Atlantic Ocean are guided there from feeding grounds prey resources. These seabirds are unique in that most off the coast of South America, presumably by a redundant species have anatomically well-developed olfactory systems set of mechanisms that possibly includes an ability to smell and are thought to have an excellent sense of smell. Results their island birth place (for review, see Lohmann, 1992). from controlled experiments performed at sea near South To explain such behaviors, it is commonly assumed that Georgia Island in the South Atlantic indicate that different animals are able to recognize and follow odors emanating species of procellariiforms are sensitive to a variety of from a distant source. This logic predicts that a recognizable scented compounds associated with their primary prey. odor signature emanates from a site, forming a gradient that These include krill-related odors (pyrazines and trimethyl- can be detected thousands of kilometers away. By some amine) as well as odors more closely associated with phy- adaptive behavioral mechanism such as turning or swim- toplankton (dimethyl sulfide, DMS). Data collected in the ming upstream in response to the odor cue, the animal context of global climatic regulation suggest that at least focuses its directional movement to locate the source of the one of these odors (DMS) tends to be associated with odor plume. -

Amphipod-Based Food Web: Themisto Gaudichaudii Caught in Nets and by Seabirds in Kerguelen Waters, Southern Indian Ocean

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 223: 261–276, 2001 Published November 28 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Amphipod-based food web: Themisto gaudichaudii caught in nets and by seabirds in Kerguelen waters, southern Indian Ocean Pierrick Bocher1, 2, Yves Cherel1,*, Jean-Philippe Labat3, Patrick Mayzaud3, Suzanne Razouls4, Pierre Jouventin1, 5 1Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, UPR-CNRS 1934, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France 2Laboratoire de Biologie et Environnement Marins, EA 1220 de l'Université de La Rochelle, 17026 La Rochelle Cedex, France 3Laboratoire d'Océanographie Biochimique et d’Ecologie, ESA 7076-CNRS/UPMC LOBEPM, Observatoire Océanologique, BP 28, 06230 Villefranche-sur-Mer, France 4Observatoire Océanologique, UMR-CNRS/UPMC 7621, Laboratoire Arago, 66650 Banyuls-sur-Mer, France 5Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive, UPR-CNRS 9056, 1919 Route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier Cedex 5, France ABSTRACT: Comparing food samples from diving and surface-feeding seabirds breeding in the Golfe du Morbihan at Kerguelen Islands to concurrent net samples caught within the predator forag- ing range, we evaluated the functional importance of the hyperiid amphipod Themisto gaudichaudii in the subantarctic pelagic ecosystem during the summer months. T. gaudichaudii occurred in high densities (up to 61 individuals m-3) in the water column, being more abundant within islands in the western part of the gulf than at open gulf and shelf stations. The amphipod was a major prey of all seabird species investigated except the South Georgian diving petrel, accounting for 39, 80, 68, 59 and 46% of the total number of prey of blue petrels, thin-billed prions, Antarctic prions, common div- ing petrels and southern rockhopper penguins, respectively. -

Appendix D New Zealand Conservation Status And

Appendix D New Zealand conservation status and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ‘Red List’ threat classification of seabirds mentioned in the report and additionally in Paragraphs 12, 23 and 24 of my evidence. New Zealand conservation status is taken from Robertson et al. (2013), and ‘Red List’ classification from http://www.iucnredlist.org/, where further information regarding categories and criteria employed by the two systems can be found. Taxa marked * were referred to in general, non-specific terms in the report (for example, northern royal albatross here was referred to as ‘unidentified royal albatross’ in the report), but are included here as species for completeness. Taxa are listed in the order they appear in the report, then in the order they appear in Paragraphs 12, 23 and 24 of my evidence. Taxa NZ Conservation Status Red List classification Wandering albatross Migrant Vulnerable Northern royal albatross* At Risk – Naturally Uncommon Endangered Southern royal albatross* At Risk – Naturally Uncommon Vulnerable Antipodean albatross Threatened – Nationally Critical Vulnerable Gibson’s albatross Threatened – Nationally Critical Vulnerable Black-browed albatross Coloniser Near Threatened Campbell albatross At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Vulnerable Grey-headed albatross Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable Endangered Southern Buller’s albatross At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Near Threatened Salvin’s albatross Threatened – Nationally Critical Vulnerable Northern giant petrel* At Risk - Naturally Uncommon Least Concern -

Themisto Amphipods in High-Latitude Marine Pelagic Food Webs

1 Predatory zooplankton on the move: 2 Themisto amphipods in high-latitude marine pelagic food webs 3 4 Charlotte Havermans*1, 2, Holger Auel1, Wilhelm Hagen1, Christoph Held2, Natalie Ensor3, Geraint Tarling3 5 1 Universität Bremen, BreMarE - Bremen Marine Ecology, Marine Zoology, 6 PO Box 330 440, 28334 Bremen, Germany 7 2 Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, 8 Am Handelshafen 12, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany 9 3 Natural Environment Research Council, 10 High Cross Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0ET, United Kingdom 11 12 *corresponding author 13 E-mail: [email protected] 14 Tel: +49 421 218 63037 15 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1126-4074 16 https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.amb.2019.02.002 17 ABSTRACT 18 Hyperiid amphipods are predatory pelagic crustaceans that are particularly prevalent in high-latitude 19 oceans. Many species are likely to have co-evolved with soft-bodied zooplankton groups such as salps 20 and medusae, using them as substrate, for food, shelter or reproduction. Compared to other pelagic 21 groups, such as fish, euphausiids and soft-bodied zooplankton, hyperiid amphipods are poorly studied 22 especially in terms of their distribution and ecology. Hyperiids of the genus Themisto, comprising seven 23 distinct species, are key players in temperate and cold-water pelagic ecosystems where they reach 24 enormous levels of biomass. In these areas, they are important components of marine food webs, and 25 they are major prey for many commercially important fish and squid stocks. In northern parts of the 26 Southern Ocean, Themisto are so prevalent that they are considered to take on the role that Antarctic 1 27 krill play further south. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

Birds and Mammals of the Subantarctic Islands

FALLA: BIRDS AND l\1AMMALS 63 General pollen analysis may not be fruitful in elucidat- ing the history of this noble composite in the The luxuriant growth of O. lyallii, and Auckland Islands. the large numbers of young plants, with germination even in cracks in the bark of ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS prostrate trunks, have often been noted-for instance by Cockayne (1904) and Dorrien- I am very grateful to Dr. R. A. Falla for a vegetation map of Ewing Island on which Fig. 4 is based and Smith (1908). Although Cockayne could see for his interest in these problems; and to Mr. K. R. no reason why it "should not be the dominant West for preparing the illustrations. forest of the Southern Islands", O. lyallii has always been considered as fighting a losing REFERENCES battle in the Auckland Islands. To Dorrien- Smith (1908) it was swamped out by rata, CHAPMAN, F. R., 1891. The outlying islands of New Zealand. Trans. N.Z. Inst. 23: 491-522. "hence its disappearance from the main COCKAYNE,L., 1904. A botanical excursion during mid- islands"; to Cockayne (1904) it was perhaps winter to the southern islands of New Zealand. a relic of a former primeval forest, "ousted by Trans. N.Z. Inst. 36: 225-333. a new formation as the conditions changed"; COCKAYNE, L., 1907. In southern seas. The Auckland Islands. N.Z. Times, 11 Dee. and he also considered "that the tree in question COCKAYNE,L., 1909. The ecological botany of the sub- may have been a member of the now vanished antarctic islands of New Zealand. -

Prion Island Boardwalk IEE 1

Initial Environmental Evaluation for Proposed Installation of a Boardwalk on Prion Island, South Georgia Prepared for the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands by Dr Liz Pasteur CONTENTS Non-technical summary..................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................5 1.1 Purpose ...........................................................................................................................5 1.2 Legislation ......................................................................................................................5 1.2.1 South Georgia legislation .......................................................................................5 1.2.2 International treaties ...............................................................................................6 1.3 Background and consultation with stakeholders ............................................................6 1.4 Visitor management at Prion Island ...............................................................................6 1.4.1 Description of current route taken by visitors ........................................................7 1.5 Boardwalk research ........................................................................................................8 1.6 Project management structure.........................................................................................8 -

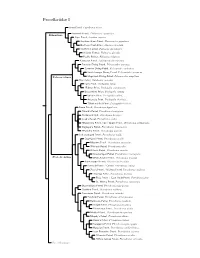

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma