Conservation Advice Pachyptila Tutur Subantarctica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Record of a Broad-Billed Prion Pachyptila Vittata at Coronation Island, South Orkney Islands

Blight & Woehler: First record of a Broad-billed Prion at Coronation Island 191 FIRST RECORD OF A BROAD-BILLED PRION PACHYPTILA VITTATA AT CORONATION ISLAND, SOUTH ORKNEY ISLANDS LOUISE K. BLIGHT1,2 & ERIC J. WOEHLER3 1Procellaria Research and Consulting, 944 Dunsmuir Road, Victoria, British Columbia, V9A 5C3, Canada 2Current address: Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z4, Canada ([email protected]) 3School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, 7005, Australia Received 15 April 2008, accepted 2 August 2008 The known breeding distribution of Broad-billed Prions Pachyptila or as a bird blown out of its normal at-sea range by strong winds vittata is restricted to Tristan da Cunha and Gough Islands in the during poor weather. Alternatively, there may be low numbers of South Atlantic Ocean and to offshore islands around New Zealand Broad-billed Prions breeding at poorly-surveyed sub-Antarctic and the Snares and Chatham Islands, with the range at sea believed colonies, such as the South Orkney Islands. Antarctic Prions are one to extend to coastal South Africa in the South Atlantic Ocean and of the most numerous seabird species in the Antarctic (Marchant & near-shore waters around New Zealand (Marchant & Higgins 1990). Higgins 1990); they nest in the South Orkney Islands (Marchant & The taxonomy of prions remains controversial, with most authors Higgins 1990). It is possible that low numbers of breeding Broad- recognising up to six species, but varying numbers of subspecies. billed Prions have been overlooked amongst their congeners. The at-sea ranges of many Southern Ocean seabird species are Although no sympatric breeding sites are known for the two species still incompletely described, with relatively few surveys obtaining (Shirihai 2002) and the presence of this bird may have been an at-sea data for prions. -

DIET and ASPECTS of FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING at SOUTH GEORGIA by P.A

DIET AND ASPECTS OF FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING AT SOUTH GEORGIA By P.A. PRINCE AND P.G. COPESTAKE ABSTRACT A subantarctic population of the Fairy Prion (Pachyprzla turtur) was studied at South Georgia in 1982-83. Full measurements of breeding birds are given, together with details of breeding habitat, the timing of the main breeding cycle events, and chick growth (weight and wing, culmen and tarsus length). Regurgitated food samples showed the diet to be mainly Crustacea (96% by weight), fish and squid comprising the rest. Of crustaceans, Antarctic krill made up 38% of items and 80% by weight. Copepods (four species, mostly Rhincalanus gigas) made up 39% of items but only 4% by weight; amphipods [three species, principally Themisto gaudichaudii made up 22% of items and 16% by weight. Diet and frequency of chick feeding are compared with those of Antarctic Prions and Blue Petrels at the same site; Fairy Prions are essentially intermediate. INTRODUCTION The Fairy Prion (Pachyptila turtur) is one of six members of a genus confined to the temperate and subantarctic regions of the Southern Hemisphere. With the Fulmar Prion (P. crassirostris), it forms the subgenus Pseudoprion. Its main area of breeding distribution is between the Antarctic Polar Front and the Subtropical Convergence. It is widespread in the New Zealand region, from the north of the North Island south to the Antipodes Islands and Macquarie Island, where only about 40 pairs survive (Brothers 1984). Although widespread in the Indian Ocean at the Prince Edward, Crozet and Kerguelen Islands, in the South Atlantic Ocean it is known to breed only on Beauchene Island (Falkland Islands) (Strange 1968, Smith & Prince 1985) and South Georgia (Prince & Croxall 1983). -

Salvin's Prion Pachyptila Salvini Captured Alive on Beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27Th July 1974

1 Salvin’s Prion Pachyptila salvini captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27th July 1974 by Mike Carter Fig. 1. Ailing Salvin’s Prion captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27 July 1974 During a gale on 27th July 1974, a Salvin’s Prion was observed flying over the breakers just beyond the rocks on the beach at Black Rocks, Victoria. Obviously debilitated, it came ashore and sought refuge in rock pools. It was rescued but died within five hours. This observation was made by a group of local and international seabird enthusiasts that included Dr Bill Bourne (from the UK), Gavin Johnstone & Noels Kerry from the Australian Antarctic Division, Peter Menkhorst, Richard Loyn, Paul Chick and me. Overseas and interstate visitors had joined locals to attend an International Ornithological Congress in Melbourne. The attached photos are recent digital copies of transparencies taken immediately after capture. Dimensions in mm measured as described in Marchant & Higgins (1990) on 29-07-74. (L = left, R = right), Wing 191; Tail 94; Tarsus (L) 36.4, (R) 35.9; Middle toe (L) 45.2, (R) 45.7; Claw (L) 8.8, (R) 8.0. Culmen (C) 31.8; Width (W) 16.4; Ratio (C)/ (W) 1.94: Bill depth max 13.2; Bill depth min 7.2. Apparent bulk = 1/4CW(BDmax+BDmin) = 2661 cub mm. I find this generated number to be a good discriminator for identifying Victorian prion corpses. 2 Figs. 2 to 5. Ailing Salvin’s Prion captured alive on beach at Black Rocks, Victoria, 27 July 1974 Identification Identification at the time was based mainly on information in Serventy, Serventy & Warham (1971). -

Part II: Parasite List by Parasite

Surveillance Vol.25 Special Issue 1998 Parasites of Birds in New Zealand Part II: Parasite list by parasite Ectoparasite Host Ectoparasite _- Host Feather mites Antrlges sp ~ continued Allopt~ssp Gull, Red-billed Chaff i11 ch Gannet, Australasian Creeper, Brown Shearwater, Flesh-footed Morepork Booby, Masked (Blue-faced) Sparrow, House Booby, Brown Saddleback, South Island Plover, Shore Tu i Sparrow, Hedge Alloptes hisetatus Tern, Caspian Canary Alloptes phaetontis minor Tropicbird, Red-tailed Quail, Brown Petrel, White-naped Blackbird Thrush, Song Allopres phaeton tis simplex Tropicbird, Red-tailed Andgopsis paxserinus Myna, Common Starling Alloptes stercorurii Skua, Arctic Anheniialges sp Fantail, South Island Ana1ge.r sp Myna, Common Fantail, North Island Skylark Greenfinch Brephosceles sp Dotterel, New Zealand Rook Mollymawk, Buller’s Parakeet, Yellow-crowned Petrel, Black-bellied Storm Yellowhammer Petrel, Northern Giant 26 Surveillance Special Issue Surveillance Vol.25 Special Issue 1998 Parasites of Birds in New Zealand Host Ectoparasite I Weka Prion, Broad-hi1 led Kea Petrel. Cook's Kakapo Pe tre I, M age11 ta (Chatham Pigeon. Rock Island Taiko) Fowl. Domestic Shearwater. Flesh-footed Shearwater, Fluttering Weka Wcka I lot t c re I. Banded Pheasant, Ring-necked Pctrcl. White-naped Pipn. New Zealand Petrel . W hi te-naped Dotterel, New Zealand Pukeko Shearwater. Sooty Rail, Banded Ovstercatcher. South Island Greenfinch Sparrow. HOLIX Pkd Stilt. Australasian Pied Kokako. South Island Stilt. Blach Weka Plover, Shore Kakapo S iIvere ye Pigeon, New Zealand Petrel. White-napcd Pukeko Petrel. Cook's Rail. Banded Petrel. Black-winged Shag. Little Petrel. Pycroft's Shag. Little Black (Little Shag, Campbell Island Black Cormorant) Shag, Stewart Island. -

Preparations for the Eradication of Mice from Gough Island: Results of Bait Acceptance Trials Above Ground and Around Cave Systems

Cuthbert, R.J.; P. Visser, H. Louw, K. Rexer-Huber, G. Parker, and P.G. Ryan. Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems Preparations for the eradication of mice from Gough Island: results of bait acceptance trials above ground and around cave systems R. J. Cuthbert1, P. Visser1, H. Louw1, K. Rexer-Huber1, G. Parker1, and P. G. Ryan2 1Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, United Kingdom. <[email protected]>. 2DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. Abstract Gough Island, Tristan da Cunha, is a United Kingdom Overseas Territory, supports globally important seabird colonies, has many endemic plant, invertebrate and bird taxa, and is recognised as a World Heritage Site. A key threat to the biodiversity of Gough Island is predation by the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus), as a result of which two bird species are listed as Critically Endangered. Eradicating mice from Gough Island is thus an urgent conservation priority. However, the higher failure rate of mouse versus rat eradications, and smaller size of islands that have been successfully cleared of mice, means that trials on bait acceptance are required to convince funding agencies that an attempted eradication of mice from Gough is likely to succeed. In this study, trials of bait acceptance were undertaken above ground and around cave systems that are potential refuges for mice during an aerial application of bait. Four trials were undertaken during winter, with rhodamine-dyed, non-toxic bait spread by hand at 16 kg/ha over 2.56 ha centred above cave systems in Trials 1-3 and over 20.7 ha and two caves in Trial 4. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

Birds and Mammals of the Subantarctic Islands

FALLA: BIRDS AND l\1AMMALS 63 General pollen analysis may not be fruitful in elucidat- ing the history of this noble composite in the The luxuriant growth of O. lyallii, and Auckland Islands. the large numbers of young plants, with germination even in cracks in the bark of ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS prostrate trunks, have often been noted-for instance by Cockayne (1904) and Dorrien- I am very grateful to Dr. R. A. Falla for a vegetation map of Ewing Island on which Fig. 4 is based and Smith (1908). Although Cockayne could see for his interest in these problems; and to Mr. K. R. no reason why it "should not be the dominant West for preparing the illustrations. forest of the Southern Islands", O. lyallii has always been considered as fighting a losing REFERENCES battle in the Auckland Islands. To Dorrien- Smith (1908) it was swamped out by rata, CHAPMAN, F. R., 1891. The outlying islands of New Zealand. Trans. N.Z. Inst. 23: 491-522. "hence its disappearance from the main COCKAYNE,L., 1904. A botanical excursion during mid- islands"; to Cockayne (1904) it was perhaps winter to the southern islands of New Zealand. a relic of a former primeval forest, "ousted by Trans. N.Z. Inst. 36: 225-333. a new formation as the conditions changed"; COCKAYNE, L., 1907. In southern seas. The Auckland Islands. N.Z. Times, 11 Dee. and he also considered "that the tree in question COCKAYNE,L., 1909. The ecological botany of the sub- may have been a member of the now vanished antarctic islands of New Zealand. -

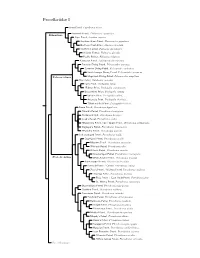

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Threats to Seabirds: a Global Assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P

1 Threats to seabirds: a global assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P. Dias1*, Rob Martin1, Elizabeth J. Pearmain1, Ian J. Burfield1, Cleo Small2, Richard A. 5 Phillips3, Oliver Yates4, Ben Lascelles1, Pablo Garcia Borboroglu5, John P. Croxall1 6 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1 - BirdLife International. The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK 10 2 - BirdLife International Marine Programme, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, SG19 2DL 11 3 – British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 12 Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 13 4 – Centre for the Environment, Fishery and Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, NR33, UK 14 5 - Global Penguin Society, University of Washington and CONICET Argentina. Puerto Madryn U9120, 15 Chubut, Argentina 16 * Corresponding author: Maria Dias, [email protected]. BirdLife International. The David 17 Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK. Phone: +44 (0)1223 747540 18 19 20 Acknowledgements 21 We are very grateful to Bartek Arendarczyk, Sophie Bennett, Ricky Hibble, Eleanor Miller and Amy 22 Palmer-Newton for assisting with the bibliographic review. We thank Rachael Alderman, Pep Arcos, 23 Jonathon Barrington, Igor Debski, Peter Hodum, Gustavo Jimenez, Jeff Mangel, Ken Morgan, Paul Sagar, 24 Peter Ryan, and other members of the ACAP PaCSWG, and the members of IUCN SSC Penguin Specialist 25 Group (Alejandro Simeone, Andre Chiaradia, Barbara Wienecke, Charles-André Bost, Lauren Waller, Phil 26 Trathan, Philip Seddon, Susie Ellis, Tom Schneider and Dee Boersma) for reviewing threats to selected 27 species. We thank also Andy Symes, Rocio Moreno, Stuart Butchart, Paul Donald, Rory Crawford, 28 Tammy Davies, Ana Carneiro and Tris Allinson for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on earlier 29 versions of the manuscript. -

Does Genetic Structure Reflect Differences in Non-Breeding Movements? a Case Study in Small, Highly Mobile Seabirds

Quillfeldt et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:160 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-1008-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Does genetic structure reflect differences in non-breeding movements? A case study in small, highly mobile seabirds Petra Quillfeldt1* , Yoshan Moodley2, Henri Weimerskirch3, Yves Cherel3, Karine Delord3, Richard A. Phillips4, Joan Navarro5, Luciano Calderón1 and Juan F. Masello1 Abstract Background: In seabirds, the extent of population genetic and phylogeographic structure varies extensively among species. Genetic structure is lacking in some species, but present in others despite the absence of obvious physical barriers (landmarks), suggesting that other mechanisms restrict gene flow. It has been proposed that the extent of genetic structure in seabirds is best explained by relative overlap in non-breeding distributions of birds from different populations. We used results from the analysis of microsatellite DNA variation and geolocation (tracking) data to test this hypothesis. We studied three small (130–200 g), very abundant, zooplanktivorous petrels (Procellariiformes, Aves), each sampled at two breeding populations that were widely separated (Atlantic and Indian Ocean sectors of the Southern Ocean) but differed in the degree of overlap in non-breeding distributions; the wintering areas of the two Antarctic prion (Pachyptila desolata) populations are separated by over 5000 km, whereas those of the blue petrels (Halobaena caerulea) and thin-billed prions (P. belcheri) show considerable overlap. Therefore, we expected the breeding populations of blue petrels and thin-billed prions to show high connectivity despite their geographical distance, and those of Antarctic prions to be genetically differentiated. Results: Microsatellite (at 18 loci) and cytochrome b sequence data suggested a lack of genetic structure in all three species. -

SHORT NOTE a Mainland Breeding Population of Fairy Prions

Notornis, 2000, Vol. 47: 119-122 0029-4470 O The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2000 SHORT NOTE A mainland breeding population of fairy prions (Pachyptila turtur), South Island, New Zealand GRAEME LOH 49 Sutcliffe Street, Dunedin, New Zealand [email protected] In July 1990, during a blue penguin (Eudyptula minor) calcareous Oligocene sandstone that has sparse vertical survey, I noticed seabird burrows on an inaccessible cliff and horizontal jointing. The cliffs are vertical or ledge near Tunnel Beach (45" 55'S, 170" 29'E) between overhanging, 70-120 m high, with many ledges and Blackhead and St Clair, Dunedin. In January 1991, the crevices occupied by roosting and breeding spotted shags ledge was reached by rope, descending 24 m from the (Stictocarbo punctatus), black-backed gulls (Larus top of this 70 m-high overhanging cliff face. The earth dominicanus), rock pigeons (Columba livia), and starlings bank was pockmarked with burrows (entrance 70-75mm (Sturnus vulgaris). A photograph in Peat & Patrick (1995: wide x 50-55rnm high) about 500 mm long. Few appeared 12) illustrates the cliffs where prions occupy three sites. to be in use and most were shallow, dug into each other, The main ledge of the 'prion cliff' colony discovered and so appeared unsuitable for breeding. I also found in July 1990, is 52 m long and up to 8 m wide. The rock the remains of a prion and prion feathers. base slopes towards the sea with a covering of up to 0.5 Breeding was confirmed in late January 1993, when a m of sand and rock debris. -

Order PROCELLARIIFORMES: Albatrosses, Petrels, Prions and Shearwaters Family PROCELLARIIDAE Leach

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 64, 78-79, 98-99 & 101-102. Order PROCELLARIIFORMES: Albatrosses, Petrels, Prions and Shearwaters Checklist Committee (1990) recognised three families within the Procellariiformes, however, four families are recognised here, with the reinstatement of Pelecanoididae, following many other recent authorities (e.g. Marchant & Higgins 1990, del Hoyo et al. 1992, Viot et al. 1993, Warham 1996: 484, Nunn & Stanley 1998, Dickinson 2003, Brooke 2004, Onley & Scofield 2007). The relationships of the families within the Procellariiformes are debated (e.g. Sibley & Alquist 1990, Christidis & Boles 1994, Nunn & Stanley 1998, Livezey & Zusi 2001, Kennedy & Page 2002, Rheindt & Austin 2005), so a traditional arrangement (Jouanin & Mougin 1979, Marchant & Higgins 1990, Warham 1990, del Hoyo et al. 1992, Warham 1996: 505, Dickinson 2003, Brooke 2004) has been adopted. The taxonomic recommendations (based on molecular analysis) on the Procellariiformes of Penhallurick & Wink (2004) have been heavily criticised (Rheindt & Austin 2005) and have seldom been followed here. Family PROCELLARIIDAE Leach: Fulmars, Petrels, Prions and Shearwaters Procellariidae Leach, 1820: Eleventh room. In Synopsis Contents British Museum 17th Edition, London: 68 – Type genus Procellaria Linnaeus, 1758. Subfamilies Procellariinae and Fulmarinae and shearwater subgenera Ardenna, Thyellodroma and Puffinus (as recognised by Checklist Committee 1990) are not accepted here given the lack of agreement about to which subgenera some species should be assigned (e.g.