Preface to the Digital Edition of the Life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Two Volumes)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Department of Commerce Telecommunications Access Minnesota

MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE TELECOMMUNICATIONS ACCESS MINNESOTA MINNESOTA RELAY AND TELEPHONE EQUIPMENT DISTRIBUTION PROGRAM 2007 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE MINNESOTA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION DOCKET NO. P999/M-08-2 JANUARY 31, 2008 Department of Commerce – Telecommunications Access Minnesota 85 7th Place East, Suite 600 St. Paul, Minnesota 55101-3165 [email protected] 651-297-8941 / 1-800-657-3599 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & PROGRAM HISTORY .........................................................2 TELECOMMUNICATIONS ACCESS MINNESOTA (TAM) ............................................4 TAM Administration ..........................................................................................................4 TAM Funding.....................................................................................................................5 Population Served ..............................................................................................................6 Role of the Public Utilities Commission............................................................................7 MINNESOTA RELAY PROGRESS.....................................................................................7 Notification to Interexchange Carriers Regarding Access to Services Through TRS....7 Notification to Carriers Regarding Public Access to Information...................................8 Emergency Preparedness...................................................................................................9 -

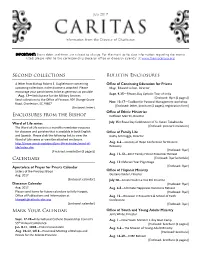

Second Collections Enclosures from The

July 2017 Information from the Diocese of Charleston IMPORTANT: Event dates and times are subject to change. For the most up-to-date information regarding the events listed, please refer to the corresponding diocesan office or diocesan calendar at www.themiscellany.org. Second collections Bulletin Enclosures A letter from Bishop Robert E. Guglielmone concerning Office of Continuing Education for Priests upcoming collections in the diocese is attached. Please Msgr. Edward Lofton, Director encourage your parishioners to be as generous as possible. Sept. 9-25—Fifteen-Day Catholic Tour of India Aug. 13—Archdiocese for the Military Services [Enclosed: flyer (2 pages)] Send collections to the Office of Finance, 901 Orange Grove Nov. 13-17—Toolbox for Pastoral Management workshop Road, Charleston, SC 29407. [Enclosed: letter, brochure (2 pages), registration form] [Enclosed: letter] Office of Ethnic Ministries Enclosures from the Bishop Kathleen Merritt, Director Word of Life series July 15—Feast Day Celebration of St. Kateri Tekakwitha [Enclosed: postcard invitation] The Word of Life series is a monthly newsletter resource for dioceses and parishes that is available in both English Office of Family Life and Spanish. Please click the following link to view the Kathy Schmugge, Director Word of Life series or view the attached enclosure. http://www.usccb.org/about/pro-life-activities/word-of- Aug. 4-6—Journey of Hope Conference for Divorce life/index.cfm Recovery [Enclosed: newsletter (3 pages)] [Enclosed: flyer] Aug. 11-12—2017 Family Honor Presenter Retreat Calendars [Enclosed: flyer/schedule] Aug. 13—Marian Year Pilgrimage Apostolate of Prayer for Priests Calendar [Enclosed: flyer] Sisters of the Precious Blood Office of Hispanic Ministry Aug. -

Xerox University Microfilms 900 North Zwb Road Ann Aibor, Michigan 40106 76 - 18,001

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produoad from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological meant to photograph and reproduce this document have bean used, the quality it heavily dependant upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing paga(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause e blurted image. You will find a good Image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. Whan a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of e large Sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with e small overlap. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could bo made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland Founding the Proprietary Colony The founding and establishment of the propriety government of Maryland was the product of competing factors—political, commercial, social, and religious. It was intertwined with the history of one family, the Calverts, who were well established among the Yorkshire gentry and whose Catholic sympathies were widely known. George Calvert had been a favorite of the Stuart king, James I. In 1625, following a noteworthy career in politics, including periods as clerk of the Privy Council, member of Parliament, special emissary abroad of the king, and a principal secretary of state, Calvert openly declared his Catholicism. This declaration closed any future possibility of public office for him. Shortly thereafter, James elevated Calvert to the Irish peerage as the baron of Baltimore. Calvert’s absence from public office afforded him an opportunity to pursue his interests in overseas colonization. Calvert appealed to Charles I, son of James, for a land grant.1 Calvert’s appeal was honored, but he did not live to see a charter issued. In 1632, Charles granted a proprietary charter to Cecil Calvert, George’s son and the second baron of Baltimore, making him Maryland’s first proprietor. Maryland’s charter was the first long-lasting one of its kind to be issued among the thirteen mainland British American colonies. Proprietorships represented a real share in the king’s authority. They extended unusual power. Maryland’s charter, which constituted Calvert and his heirs as “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietaries of the Region,” might have been “the best example of a sweeping grant of power to a proprietor.” Proprietors could award land grants, confer titles, and establish courts, which included the prerogative of hearing appeals. -

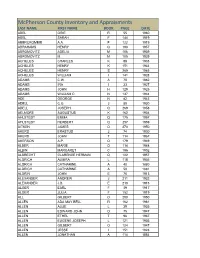

Mcpherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A

McPherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A. F 122 1919 ABRAHAMS HENRY Q 193 1957 ABROMOVITZ ADELIA M 106 1939 ABROMOVITZ M. M 105 1939 ACHILLES CHARLES K 88 1933 ACHILLES HENRY K 151 1934 ACHILLES HENRY S 289 1965 ACHILLES WILLIAM I 141 1928 ADAMS C.W. A 70 1882 ADAMS IRA I 33 1927 ADAMS JOHN H 129 1925 ADAMS WILLIAM C. N 147 1944 ADE GEORGE N 82 1943 ADELL C.G. J 80 1930 ADELL JOSEPH Q 269 1958 AELMORE AUGUSTUS K 162 1934 AHLSTEDT EMMA Q 175 1957 AHLSTEDT HERBERT Q 297 1959 AITKEN JAMES O 270 1950 AKERS ERASTUS J 74 1930 AKERS JOHN T 114 1967 AKERSON A.P. O 179 1949 ALBER MARIE O 114 1948 ALBIN MARGARET C 196 1902 ALBRECHT CLARENCE HERMAN Q 122 1957 ALDRICH ALMIRA L 118 1936 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 40 1880 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 50 1881 ALDRIN JOHN E 76 1913 ALEXANDER ANDREW J 211 1932 ALEXANDER J.B. E 210 1915 ALGER EARL F 39 1917 ALGER JULIA F 152 1919 ALL GILBERT O 290 1950 ALLEN ADA MAY BELL R 162 1961 ALLEN ALLIE L 39 1935 ALLEN EDWARD JOHN O 75 1947 ALLEN ETHEL T 96 1967 ALLEN EUGENE JOSEPH L 121 1936 ALLEN GILBERT O 124 1947 ALLEN JESSE I 151 1928 ALLEN JONATHAN A 114 1884 LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ALLEN LURA ELLEN Q 267 1958 ALLEN MARTHA C 174 1902 ALLEN NORMAN A 7 1878 ALLEN O.D. -

![1867-12-18, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5874/1867-12-18-p-315874.webp)

1867-12-18, [P ]

Home and Other Itema. Saw, you and Doc. make a good team Mews and Item*. i take part in it Ole Bull, the world- 'fh* Dlckriu. | Those irreverent lads who called names W. \V. Bornartl, of<j<ranper,Minn., call Jhc limes. The Commonwealth Ins. Co. is a new and Both Houses will ndjonrn on the ?0th renowned Norwegian violinist, arrived in New York 1ms fairly Out-Bostoned Bos after a certain "bald head"' of old, deserv* Hotel Loo£*l ed to see as last week on liis wny east.— 1 THERE IS A NKWLY FINISHED llOTlt A# | strong institution established in Decorah.1 iirst., until the 6th of January One J New York last week, en route for Chicago, ton in the Dickens excitement. The sale ed their untimely end, because nt thnt time When he returns we will say he is a pret of tickets for the Dickens readings com no panacea had been discovered to restore X.I 3VI E 8PRINO8, McOHEOUK, DEC. 18, 1867 Is that young and thriving city to be the week ago the street cars of New York was where he is expected to arrive some time ty good man, if he will permit it. We are menced at Steinwav Ilall at nine o'clock the human Iiair upon the bald spots. But Oi* nit McOreook Rahwit, INHtMy. Insurance center of the whole west? Suo blockaded with snow The Chicago Dai-1 this week The commissioner of pen- this morning, and lon^ before the hour a now, Ring's Vegetable Ambrosia is known •ltvar? trliid to *te the Chesterfield Mer- That wants to be sold lor eauh or exchanged for a' . -

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands As Either Premium Or Discount

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands as either Premium or Discount Category Name of Cigarette Brand Premium Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Chesterfield, Davidoff, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Dunhill International, Eve, Kent, Kool, L&M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, Mild Seven, More, Nat Sherman, Newport, Now, Parliament, Players, Quest, Rothman’s, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Tareyton, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston, Raleigh, Business Club Full Flavor, Ronhill, Dreams Discount 24/7, 305, 1839, A1, Ace, Allstar, Allway Save, Alpine, American, American Diamond, American Hero, American Liberty, Arrow, Austin, Axis, Baileys, Bargain Buy, Baron, Basic, Beacon, Berkeley, Best Value, Black Hawk, Bonus Value, Boston, Bracar, Brand X, Brave, Brentwood, Bridgeport, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, BV, Calon, Cambridge, Campton, Cannon, Cardinal, Carnival, Cavalier, Champion, Charter, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Circle Z, Class A, Classic, Cobra, Complete, Corona, Courier, CT, Decade, Desert Gold, Desert Sun, Discount, Doral, Double Diamond, DTC, Durant, Eagle, Echo, Edgefield, Epic, Esquire, Euro, Exact, Exeter, First Choice, First Class, Focus, Fortuna, Galaxy Pro, Gauloises, Generals, Generic/Private Label, Geronimo, Gold Coast, Gold Crest, Golden Bay, Golden, Golden Beach, Golden Palace, GP, GPC, Grand, Grand Prix, G Smoke, GT Ones, Hava Club, HB, Heron, Highway, Hi-Val, Jacks, Jade, Kentucky Best, King Mountain, Kingsley, Kingston, Kingsport, Knife, Knights, -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 a GOVERNMENT SERVICES

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 A GOVERNMENT SERVICES # Girl Names # Girl Names # Girl Names 1 A 1 Adelaide 4 Aisha 2 Aaisha 2 Adelle 1 Aisley 1 Aajah 1 Adelynn 1 Aislin 1 Aaliana 2 Adena 1 Aislinn 2 Aaliya 1 Adeoluwa 2 Aislyn 10 Aaliyah 1 Adia 1 Aislynn 1 Aalyah 1 Adiella 1 Aisyah 1 Aarona 5 Adina 1 Ai-Vy 1 Aaryanna 1 Adreana 1 Aiyana 1 Aashiyana 1 Adreanna 1 Aja 1 Aashna 7 Adria 1 Ajla 1 Aasiya 2 Adrian 1 Akanksha 1 Abaigeal 7 Adriana 1 Akasha 1 Abang 11 Adrianna 1 Akashroop 1 Abbegael 1 Adrianne 1 Akayla 1 Abbegayle 1 Adrien 1 Akaysia 15 Abbey 1 Adriene 1 Akeera 2 Abbi 3 Adrienne 1 Akeima 3 Abbie 1 Adyan 1 Akira 8 Abbigail 1 Aedan 1 Akoul 1 Abbi-Gail 1 Aeryn 1 Akrity 47 Abby 1 Aeshah 2 Alaa 3 Abbygail 1 Afra 1 Ala'a 2 Abbygale 1 Afroz 1 Alabama 1 Abbygayle 1 Afsaneh 1 Alabed 1 Abby-Jean 1 Aganetha 5 Alaina 1 Abella 1 Agar 1 Alaine 1 Abha 6 Agatha 1 Alaiya 1 Abigael 1 Agel 11 Alana 83 Abigail 2 Agnes 1 Alanah 1 Abigale 1 Aheen 4 Alanna 1 Abigayil 1 Ahein 2 Alannah 4 Abigayle 1 Ahlam 1 Alanta 1 Abir 2 Ahna 1 Alasia 1 Abrial 1 Ahtum 1 Alaura 1 Abrianna 1 Aida 1 Alaya 3 Abrielle 4 Aidan 1 Alayja 1 Abuk 2 Aideen 5 Alayna 1 Abygale 6 Aiden 1 Alaysia 3 Acacia 1 Aija 1 Alberta 1 Acadiana 1 Aika 1 Aldricia 1 Acelyn 1 Aiko 2 Alea 1 Achwiel 1 Aileen 7 Aleah 1 Adalien 1 Aiman 1 Aleasheanne 1 Adana 7 Aimee 1 Aleea 2 Adanna 2 Aimée 1 Aleesha 2 Adara 1 Aimie 2 Aleeza 1 Adawn-Rae 1 Áine 1 Aleighna 1 Addesyn 1 Ainsleigh 1 Aleighsha 1 Addisan 12 Ainsley 1 Aleika 10 Addison 1 Aira 1 Alejandra 1 Addison-Grace 1 Airianna 1 Alekxandra 1 Addyson 1 Aisa -

AAMA) List Updated 9/17/2020

Connecticut residents that are CMAs (AAMA) List Updated 9/17/2020 First Name Last Name Credential Karin Abalan CMA (AAMA) Emma Abruzzo CMA (AAMA) Camice Acevedo CMA (AAMA) Nathalie Acevedo-Muniz CMA (AAMA) Margarita Acosta CMA (AAMA) Vickie Adams CMA (AAMA) Jamil Ahmed CMA (AAMA) Jennifer Aiken CMA (AAMA) Sahbaa Al Bayati CMA (AAMA) Alyssa Alarcon CMA (AAMA) Betsy Aldridge CMA (AAMA) Brittani Algarin CMA (AAMA) Zenaida Alicea CMA (AAMA) Scarlett Alquijay CMA (AAMA) Ana Alvarez CMA (AAMA) Brianda Alvarez CMA (AAMA) Jennifer Amaral CMA (AAMA) Charlene Ames CMA (AAMA) Elisa Kelly Amill CMA (AAMA) Tina Ammerman CMA (AAMA) Holly Anderson CMA (AAMA) Ryan Anderson CMA (AAMA) Frances Andino CMA (AAMA) Brandi Andres CMA (AAMA) Theresa Andrews CMA (AAMA) Sandra Angel CMA (AAMA) Lorie Annatone CMA (AAMA) Kayla Anseeuw CMA (AAMA) Michelle Antonini CMA (AAMA) Bonnie Appleton CMA (AAMA) Parthena Athanasiades CMA (AAMA) Monica Auclair CMA (AAMA) Deirdre Austin CMA (AAMA) Raegan Avallone CMA (AAMA) Stephanie Avila CMA (AAMA) Rosalyn Aybar CMA (AAMA) Magali Ayres CMA (AAMA) Jessica Backer CMA (AAMA) Kristin Bacon CMA (AAMA) Jonathan Baez CMA (AAMA) Florina Balavender CMA (AAMA) Lyndsay Baldwin CMA (AAMA) Sally Ballantoni CMA (AAMA) Mickell Balonze CMA (AAMA) Connecticut residents that are CMAs (AAMA) List Updated 9/17/2020 Niloufer Banaji CMA (AAMA) Kimberly Bankowski CMA (AAMA) Amber Barber CMA (AAMA) Laura Barbero CMA (AAMA) Michael Barbieri-May CMA (AAMA) Kimberly Barbour CMA (AAMA) Rebecca Barnes CMA (AAMA) Crystal Barnes CMA (AAMA) Naomi Barone CMA -

Principal Facts of the Earth's Magnetism and Methods Of

• * Class Book « % 9 DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE U. S. COAST AND GEODETIC SURVEY E. LESTER JONES, Superintendent PRINCIPAL FACTS OF THE EARTH’S MAGNETISM AND METHODS OF DETERMIN¬ ING THE TRUE MERIDIAN AND THE MAGNETIC DECLINATION [Reprinted from United States Magnetic Declination Tables and Isogonic Charts for 1902] [Reprinted from edition of 1914] WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1919 ( COAST AND GEODETIC SURVEY OFFICE. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE U. S. COAST AND GEODETIC SURVEY »» E. LESTER JONES, Superintendent PRINCIPAL FACTS OF THE EARTH’S MAGNETISM AND METHODS OF DETERMIN¬ ING THE TRUE MERIDIAN AND THE MAGNETIC DECLINATION [Reprinted from United States Magnetic Declination Tables and Isogonic Charts for 1902 ] i [ Reprinted from edition of 1914] WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 4 n; «f B. AUG 29 1913 ft • • * C c J 4 CONTENTS. Page. Preface. 7 Definitions. 9 Principal Facts Relating to the Earth’s Magnetism. Early History of the Compass. Discovery of the Lodestone. n Discovery of Polarity of Lodestone. iz Introduction of the Compass..... 15 Improvement of the Compass by Petrius Peregrinus. 16 Improvement of the Compass by Flavio Gioja. 20 Derivation of the word Compass. 21 Voyages of Discovery. 21 Compass Charts. 21 Birth of the Science of Terrestrial Magnetism. Discovery of the Magnetic Declination at Sea. 22 Discovery of the Magnetic Declination on Land. 25 Early Methods for Determining the Magnetic Declination and the Earliest Values on Land. 26 Discovery of the Magnetic Inclination. 30 The Earth, a Great Magnet. Gilbert’s “ De Magnete ”.'. 34 The Variations of the Earth’s Magnetism. Discovery of Secular Change of Magnetic Declination. 38 Characteristics of the Secular Change. -

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary Technical Report June 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH TEAM ................................................................................................................... iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY PROTOCOL ........................................................................................................... 1 2.1 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 1 2.2 SAMPLE AND RECRUITMENT ................................................................................. 2 3.0 STUDY CONTENT ............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 STUDY 1: HEALTH WARNING MESSAGES ............................................................... 3 3.2 STUDY 2: CIGARETTE PACKAGING ......................................................................... 4 4.0 MEASURES...................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................... 6 4.2 QUESTIONNAIRE CONTENT ................................................................................... 6 5.0 SAMPLE INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 9 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................ -

Genealogical Sketch Of

Genealogy and Historical Notes of Spamer and Smith Families of Maryland Appendix 2. SSeelleecctteedd CCoollllaatteerraall GGeenneeaallooggiieess ffoorr SSttrroonnggllyy CCrroossss--ccoonnnneecctteedd aanndd HHiissttoorriiccaall FFaammiillyy GGrroouuppss WWiitthhiinn tthhee EExxtteennddeedd SSmmiitthh FFaammiillyy Bayard Bache Cadwalader Carroll Chew Coursey Dallas Darnall Emory Foulke Franklin Hodge Hollyday Lloyd McCall Patrick Powel Tilghman Wright NEW EDITION Containing Additions & Corrections to June 2011 and with Illustrations Earle E. Spamer 2008 / 2011 Selected Strongly Cross-connected Collateral Genealogies of the Smith Family Note The “New Edition” includes hyperlinks embedded in boxes throughout the main genealogy. They will, when clicked in the computer’s web-browser environment, automatically redirect the user to the pertinent additions, emendations and corrections that are compiled in the separate “Additions and Corrections” section. Boxed alerts look like this: Also see Additions & Corrections [In the event that the PDF hyperlink has become inoperative or misdirects, refer to the appropriate page number as listed in the Additions and Corrections section.] The “Additions and Corrections” document is appended to the end of the main text herein and is separately paginated using Roman numerals. With a web browser on the user’s computer the hyperlinks are “live”; the user may switch back and forth between the main text and pertinent additions, corrections, or emendations. Each part of the genealogy (Parts I and II, and Appendices 1 and 2) has its own “Additions and Corrections” section. The main text of the New Edition is exactly identical to the original edition of 2008; content and pagination are not changed. The difference is the presence of the boxed “Additions and Corrections” alerts, which are superimposed on the page and do not affect text layout or pagination.