Baranovich the Trilogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizensâ•Ž Motives Near

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Green, Jordan, "From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/holocaust/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green History 395 James Madison University Spring 2018 Dr. Michael J. Galgano The Holocaust has raised difficult questions since its end in April 1945 including how could such an atrocity happen and how could ordinary people carry out a policy of extermination against a whole race? To answer these puzzling questions, most historians look inside the Nazi Party to discern the Holocaust’s inner-workings: official decrees and memos against the Jews and other untermenschen1, the role of the SS, and the organization and brutality within concentration and extermination camps. However, a vital question about the Holocaust is missing when examining these criteria: who was watching? Through research, the local inhabitants’ knowledge of a nearby concentration camp, extermination camp or mass shooting site and its purpose was evident and widespread. -

Déportés À Auschwitz. Certains Résis- Tion D’Une Centaine, Sont Traqués Et Tent Avec Des Armes

MORT1943 ET RÉSISTANCE BIEN QU’AYANT rarement connu les noms de leurs victimes juives, les nazis entendaient que ni Zivia Lubetkin, ni Richard Glazar, ni Thomas Blatt ne survivent à la « solution finale ». Ils survécurent cependant et, après la Shoah, chacun écrivit un livre sur la Résistance en 1943. Quelque 400 000 Juifs vivaient dans le ghetto de Varsovie surpeuplé, mais les épi- démies, la famine et les déportations à Treblinka – 300 000 personnes entre juillet et septembre 1942 – réduisirent considérablement ce nombre. Estimant que 40 000 Juifs s’y trouvaient encore (le chiffre réel approchait les 55 000), Heinrich Himmler, le chef des SS, ordonna la déportation de 8 000 autres lors de sa visite du ghetto, le 9 janvier 1943. Cependant, sous la direction de Mordekhaï Anielewicz, âgé de 23 ans, le Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ZOB, Organisation juive de combat) lança une résistance armée lorsque les Allemands exécutèrent l’ordre d’Himmler, le 18 janvier. Bien que plus de 5 000 Juifs aient été déportés le 22 janvier, la Résistance juive – elle impliquait aussi bien la recherche de caches et le refus de s’enregistrer que la lutte violente – empêcha de remplir le quota et conduisit les Allemands à mettre fin à l’Aktion. Le répit, cependant, fut de courte durée. En janvier, Zivia Lubetkin participa à la création de l’Organisation juive de com- bat et au soulèvement du ghetto de Varsovie. « Nous combattions avec des gre- nades, des fusils, des barres de fer et des ampoules remplies d’acide sulfurique », rapporte-t-elle dans son livre Aux jours de la destruction et de la révolte. -

The Holocaust in Hungary

THE HOLOCAUST IN HUNGARY When the Germans entered Hungary on March 19, 1944, its more than 800,000 Jews were the last intact Jewish community in occupied Europe. Between May 14 and July 9 – in less than two months and on the very eve of Allied victory – more than 400,000 were deported to Auschwitz, where 75% were killed immediately. Such swift, concentrated destruction could not have happened without the help of local collaborators – help Adolf Eichmann clearly expected when he brought only 200 staff with him to oversee the deportations. Collaborators included the government, the right wing parties, and the law-enforcement agencies, bolstered by the tacit approval of most non-Jews and Church authorities. Indeed, laws allowing synagogues to be expropriated for secular use and the many private requests for real estate and other property formerly owned by Jews, indicate that few expected any Jews to return. The Vatican, the International Red Cross, the Allies, and the neutral powers also had a role in the catastrophe, since it took place when details of the “Final Solution” – especially the Hungarian situation – were already known to them. In summer 1944, at the height of the deportations, the Allies rejected Jewish underground leaders’ pleas to bomb Auschwitz and the rail lines leading to it, claiming that bombers flying from Britain were incapable of attacking Poland and could not be diverted to targets not "military related." To be sure, pressure from President Roosevelt, Sweden’s king, and the pope – combined with the success of Operation Overlord and the Soviet Union’s summer offensive and Allied intimations they would carpet-bomb Budapest if its Jews were deported – did force Regent Miklos Horthy to stop the trains on July 7, 1944. -

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

„Grossaktion” (22 July 1942 – 21 September 1942)

„Grossaktion” (22 July 1942 – 21 September 1942) The Nazi authorities started to carry out the plans for annihilating European Jews from the second half of 1941, when German troops marched into the USSR. If we deem the activities of the Einsatzgruppen as phase one of the extermination and the ones commenced nine months later (“Operation Reinhardt”) as its escalation, the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto – conducted between 22 July and 21 September 1942 under the codename “Grossaktion” – should be regarded as a supplement of the genocide plan. All of them were parts of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”. Announcements. In the afternoon of July 20th, cars with SS officers start appearing in the Ghetto. Guard posts at the exits leading to the “Aryan District” have been reinforced. A security cordon was established along the walls, comprised of uniformed Lithuanian, Latvian, and Ukrainian troops. Stefan Ernest, working at the Ghetto Employment Office, noted at that time, his feeling of impending cataclysm to erupt in Warsaw, the largest conglomeration of Jews in German-occupied Europe: “It was clear that some invisible hand was orchestrating a spectacle that is yet to begin. The current goings on are just a tuning of instruments getting ready to play some dreadful symphony. Some sort of »La danse macabre«” . On the same day, when many Judenrat representatives were arrested in the afternoon and transported to the Pawiak prison, Ernest wrote: “The Game has begun”. The city was gripped in fear. Everything indicated that the future of the Jews was already settled. The screenplay, methods and manner of its execution remained unknown. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

'Don't Sign It Just Yet Mr Balfour!'

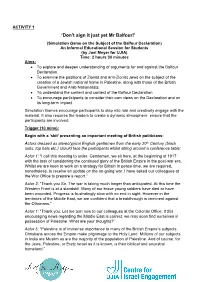

ACTIVITY 1 ‘Don’t sign it just yet Mr Balfour!’ (Simulation Game on the Subject of the Balfour Declaration) An Informal Educational Session for Students (by Joel Meyer for UJIA) Time: 2 hours 30 minutes Aims: To explore and deepen understanding of arguments for and against the Balfour Declaration. To examine the positions of Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews on the subject of the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine, along with those of the British Government and Arab Nationalists. To understand the content and context of the Balfour Declaration To encourage participants to consider their own views on the Declaration and on its long-term impact. Simulation Games encourage participants to step into role and creatively engage with the material. It also requires the leaders to create a dynamic atmosphere ensure that the participants are involved. Trigger (10 mins): Begin with a ‘skit' presenting an important meeting of British politicians: Actors dressed as stereotypical English gentlemen from the early 20th Century (black suits, top hats etc.) should face the participants whilst sitting around a conference table: Actor 1: “I call this meeting to order. Gentlemen, we sit here, at the beginning of 1917 with the task of considering the continued glory of the British Empire in the post-war era. Whilst we are keen to work on a strategy for Britain in peace time, we are required, nonetheless, to receive an update on the on-going war. I have asked our colleagues at the War Office to prepare a report.” Actor 2: “Thank you Sir. The war is taking much longer than anticipated. -

The Jerusalem Report February 6, 2017 Wikipedia Wikipedia

Books A traitor in Budapest Rudolf Kasztner was not a hero but an unscrupulous Nazi collaborator, insists British historian Paul Bogdanor in his new book By Tibor Krausz REZSŐ KASZTNER was a much-maligned Was Kasztner, the de facto head of the Bogdanor’s book is a meticulously re- hero of the Holocaust. Or he was a villain- Zionist Aid and Rescue Committee in Bu- searched, cogently argued and at times ous Nazi collaborator. It depends who you dapest, eagerly liaising with Adolf Eich- riveting indictment of Kasztner, which ask and how you look at it. Over 70 years mann and his henchmen so as to save any is bound to reopen debate on the wartime after the end of World War II and almost 60 Hungarian Jews he could from deportation Zionist leader’s role in the destruction of years after his death, the Jewish-Hungarian and certain death in Auschwitz-Birkenau? Hungary’s Jewish community. Zionist leader remains a highly controver- Or was he doing so out of sheer self-inter- sial figure. est in order to make himself indispensable IN APRIL and May 1944, the author To his defenders, like Israeli histori- to the Nazis by helping send hundreds of demonstrates at length, Kasztner knew an Shoshana Ishoni-Barri and Hungar- thousands of other Jews blindly to their fate full well that the Nazis were busy deport- ian-born Canadian writer Anna Porter, through willful deception? ing Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, where the author of “Kasztner’s Train” (2007), In his book “Kasztner’s Crime,” Brit- the gas chambers awaited them. -

TACTICS of RESISTANCE a Two-Part Lesson (45-60 Minutes Each) for 9Th – 12Th Grade Students CURRICULUM Photo: Channukah: Kiel Germany, 1932

Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation www.jewishpartisans.org HISTORY LEADERSHIP ETHICS JEWISH VALUES TACTICS OF RESISTANCE a two-part lesson (45-60 minutes each) for 9th – 12th grade students CURRICULUM Photo: Channukah: Kiel Germany, 1932. Rachel Posner, wife of Rabbi Dr. Akiva Posner, took this photo just before lighting the candles for Channukah and Shabbat. Source: Posner family/USHMM. CONTENTS 1 Who are the Jewish Partisans? Lesson Overview 2 How to Use This Lesson Use primary sources to expand your 3 Overview students thinking about the spectrum of 4 Guide possible responses to genocide and other forms of aggression—from non-violent to 5 Setup armed resistance. 6 - 8 Procedure Includes innovative tools to help your 9 - 13 Attachments students analyze conflict and brainstorm 14 - 23 Jewish Resistance Slideshow solutions to aggression in their own lives. 24 - 29 Appendix Conforms to Common Core Standards jewishpartisans.org/standards ©2012 - 2014 JEWISH PARTISAN EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION Tactics of Resistance Who Are the Jewish Partisans? par·ti·san noun: a member of an organized body of fighters who attack or harass an enemy, especially within occupied territory; a guerrilla During World War II, the majority of European Jews were deceived by a monstrous and meticulous disinformation campaign. The Germans and their collaborators isolated and imprisoned Jews in ghettos. Millions were deported into concentration camps or death camps—primarily by convincing them that they we were being sent to labor camps instead. In reality, most Jews who entered these so-called “work camps” would be starved, murdered or worked to death. Yet approximately 30,000 Jews, many of whom were teenagers, escaped the Nazis to form or join organized resistance groups. -

Biography of Chaim Weizmann

BIOGRAPHY OF CHAIM WEIZMANN Chaim Weizmann was born in the small village of Motol (Motyli, now Motal') near Pinsk in Belarus (at that time part of the Russian Empire). After Cheder and Gymnasium, Weizmann started to study chemistry in Darmstadt at the Technischen Hochschule in 1892, and from 1894 on at the Royal Technical Hochschule in Berlin. In 1897, Weizmann moved to Fribourg in Switzerland where he received his PhD in chemistry in 1899 with summa cum laude. He then lectured in chemistry at the University of Geneva between 1901 and 1903. He became a British subject in 1910, and, while a lecturer at Manchester, he became famous for discovering how to use bacterial fermentation to produce large quantities of relevant substances. He is considered to be the father of industrial fermentation. He used the bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum (the Weizmann organism) to produce acetone. Acetone was used in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants critical to the Allied war effort. Weizmann transferred the rights to the manufacture of acetone to the Commercial Solvents Corporation in exchange for royalties. After the Shell Crisis of 1915 during World War I, he was director of the British Admiralty laboratories from 1916 until 1919. During World War II, he was an honorary adviser to the British Ministry of Supply and did research on synthetic rubber and high-octane gasoline. Already since 1918, Weizmann was engaged, together with Albert Einstein and Hugo Bergman in the foundation of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the president of which he became from 1932 until 1952. Living in Rechowot, he founded a research institution, which became famous as today’s Weizmann- Institute. -

World War II, Shoah and Genocide

International Conference “The Holocaust: Remembrance and Lessons” 4 - 5 July 2006, Riga, Latvia Evening lecture at the Big Hall of Latvian University The Holocaust in its European Context Yehuda Bauer Allow me please, at the outset, to place the cart firmly before the horse, and set before you the justification for this paper, and in a sense, its conclusion. The Holocaust – Shoah – has to be seen in its various contexts. One context is that of Jewish history and civilisation, another is that of antisemitism, another is that of European and world history and civilisation. There are two other contexts, and they are very important: the context of World War II, and the context of genocide, and they are connected. Obviously, without the war, it is unlikely that there would have been a genocide of the Jews, and the war developments were decisive in the unfolding of the tragedy. Conversely, it is increasingly recognized today that while one has to understand the military, political, economic, and social elements as they developed during the period, the hard core, so to speak, of the World War, its centre in the sense of its overall cultural and civilisational impact, were the Nazi crimes, and first and foremost the genocide of the Jews which we call the Holocaust, or Shoah. The other context that I am discussing here is that of genocide – again, obviously, the Holocaust was a form of genocide. If so, the relationship between the Holocaust and other genocides or forms of genocide are crucial to the understanding of that particular tragedy, and of its specific and universal aspects. -

Poland and the Holocaust – Facts and Myths

The Good Name Redoubt The Polish League Against Defamation Poland and the Holocaust – facts and myths Summary 1. Poland was the first and one of the major victims of World War II. 2. The extermination camps, in which several million people were murdered, were not Polish. These were German camps in Poland occupied by Nazi Germany. The term “Polish death camps” is contradictory to historical facts and grossly unfair to Poland as a victim of Nazi Germany. 3. The Poles were the first to alert European and American leaders about the Holocaust. 4. Poland never collaborated with Nazi Germany. The largest resistance movement in occupied Europe was created in Poland. Moreover, in occupied Europe, Poland was one of the few countries where the Germans introduced and exercised the death penalty for helping Jews. 5. Hundreds of thousands of Poles – at the risk of their own lives – helped Jews survive the war and the Holocaust. Poles make up the largest group among the Righteous Among the Nations, i.e. citizens of various countries who saved Jews during the Holocaust. 6. As was the case in other countries during the war, there were cases of disgraceful behaviour towards Jews in occupied Poland, but this was a small minority compared to the Polish society as a whole. At the same time, there were also instances of disgraceful behaviour by Jews in relation to other Jews and to Poles. 7. During the war, pogroms of the Jewish people were observed in various European cities and were often inspired by Nazi Germans. Along with the Jews, Polish people, notably the intelligentsia and the political, socio-economic and cultural elites, were murdered on a massive scale by the Nazis and by the Soviets.