SCURO, Daniel Ervlnn, 1933

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the French Maîtresse En Titre: How Royal Mistresses Utilized Liminal Space to Gain Power and Access by Marine Elia

The Role of the French Maîtresse en titre: How Royal Mistresses Utilized Liminal Space to Gain Power and Access By Marine Elia Senior Honors Thesis Romance Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 4/19/2021 Approved: Jessica Tanner, Thesis Advisor Valérie Pruvost, Reader Dorothea Heitsch, Reader 2 Table of Contents Introduction…Page 3 Chapter 1: The Liminal Space of the Maîtresse-en-titre…Page 15 Cahpter 2: Fashioning Power…Page 24 Chapter 3: Mistresses and Celebrity…Page 36 Conclusion…Page 52 Bibliography…Page 54 Acknowledgments…Page 58 3 Introduction Beginning in the mid-fifteenth century, during the reign of Charles VII (1422- 1461), the “royal favorite” (favorite royale) became a quasi-official position within the French royal court (Wellman 37). The royal favorite was an open secret of French courtly life, an approved, and sometimes encouraged, scandal that helped to define the period of a king's reign. Boldly defying Catholic tenants of marriage, the position was a highly public transgression of religious mores. Shaped during the Renaissance by powerful figures such as Diane de Poitiers and Agnès Sorel, the role of the royal mistress evolved through the centuries as each woman contributed their own traditions, further developing the expectations of the title. Some used their influence to become powerful political actors, often surpassing that of the king’s ministers, while other women used their title to patronize the arts. Using the liminal space of their métier, royal mistresses created opportunities for themselves using the limited spaces available to women in Ancien Régime France. Historians and writers have been captivated by the role of the royal mistress for centuries, studying their lives and publishing both academic and non-academic biographies of individual mistresses. -

Kings and Courtesans: a Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2008 Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses Shandy April Lemperle The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lemperle, Shandy April, "Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses" (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1258. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KINGS AND COURTESANS: A STUDY OF THE PICTORIAL REPRESENTATION OF FRENCH ROYAL MISTRESSES By Shandy April Lemperlé B.A. The American University of Paris, Paris, France, 2006 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Fine Arts, Art History Option The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2008 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School H. Rafael Chacón, Ph.D., Committee Chair Department of Art Valerie Hedquist, Ph.D., Committee Member Department of Art Ione Crummy, Ph.D., Committee Member Department of Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Lemperlé, Shandy, M.A., Spring 2008 Art History Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses Chairperson: H. -

MINUTES of the 69 MEETING of AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD at the VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO on WEDNESDAY 25 JUNE 2014 Present

MINUTES OF THE 69th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT THE VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO ON WEDNESDAY 25th JUNE 2014 Present: - Peter Cole - Secretary. There were apologies from Rupert Clark due to work commitments 1. Chairman and Treasurer's Report In Rupert’s absence Peter reported that Middleton Cheney is holding a photographic exhibition on Saturday 19th July from 2pm to 4.30pm in All Saints Church, entitled “The Village – Then and Now”. There will be about 50 photos of Middleton Cheney taken between 1900 and 1930, accompanied by photos of the same view taken today. 2. Royal Mistresses Roger Powell The talk covers the period from 1509 to the present day, and concentrates on people who were royal mistresses for at least ten years. Indeed one was a mistress for 36 years. In many cases from a psychological point of view she was not just an object of desire but she more or less became a second wife, and sometimes even a mother to the king. The origin of the role in the early days of the Middle Ages derives from the many loveless royal marriages, as for kings the main reason for a marriage was to secure or maintain an alliance to build his empire or strengthen his position against enemies. Once a queen had given the king one or two heirs, he would forget or even abandon her and take a mistress. In England a royal mistress did not become a feature of court society until the 17th century. In France they had been around in the mid-1600s, but it took a while before England followed suit. -

The Historicity of Papyrus Westcar*

The Historicity of Papyrus Westcar Hays, H.M. Citation Hays, H. M. (2002). The Historicity of Papyrus Westcar. Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 129, 20-30. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16163 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16163 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 20 H. M. Hays: Historicity of p\X"e~tcar zAs 129 (2002) HAROLD M. HAYS The Historicity ofPapyrus Westcar* An approach first explicitly evident 1n treated as exhibiting an "historisch vollig richti Meyer's monumental 1909 Geschichte des Al gen Kern," as representing a 'Widerspiegelung tertums" Papyms Westcar has been persistently' der realen Vorgiinge"; from Dynasty 4 to 5. This has been done even in the face of the tale's fabulous elements - when these are mentioned, * A version ofthis article was presented on 28 April it is only in order to dismiss them from the 2000 at the University of California, Berkeley, at the equation· of a historical inquiry'. As this ap 51st Annual Meeting of the American Research Center proach endures~ despite protestations made in in Egypt. It has benefited from comments nude by John Brinkmann, Peter F. Donnan, Janet JOh0500, and passing by Goedicke recently in this journal", David O'Connor, though responsibility for the work there are grounds for a concentrated inquiry into remains mine. the text's worth as a historical trace. For my own 2 1 E. Merer, Geschichte -

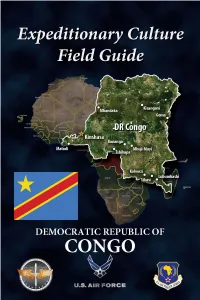

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Sekecan and Other Influences 01 Six

SEKECAN AND OTHER INFLUENCES 01 SIX ELIZABETHAN REVENGE PLAYS APPROVED* I<d»<ti2!ii5-^25axslwi Profeaeor ^. i. Direct or af He" feej/^traent' of th« SENECAK AID OTHER IRFLTJENCBS 01 SIX amSSTHAI KEVENGE PLAYS THESIS Present ©cl to th© Sra&uat® Council of tfa« Berth Texas Stat® €©ll®g® in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For th© B«gr®« of MASTER OF ARTS Bit 223584 Marilyn Fisher, R# A, Thornton, Texas August, 195S 2235m TABLE OP CO*T**rS Chapter ?ag9 X* THE VOGtflS or StfUSCA, 1670-1600 1 Definition of tha Tragedy of Blood Elements of Senaoaii f nige^y Appeal of 3an«oan Eras® Direct Imitations of Son#@a Departure iwm. Bmmmm Mod®! II* PROBLEMS OP CBRONOStOGTZt SOURCES, ARB AUTHORSHIP 14 2r«» ^i.ii.iwii>iiiliiv,i.ii foe Jew of Malta The' frlrif t Part of Xerotilino III. I1TEHRELAf IOKS Of SIX TRAGEDIES OP 8BVSR8X *2? lesta®©* of Each Revenge Play 5«qmbs Heaeata in tbe Tragediea of Revenge Mutual Dependence of Kyd# Marlowe, and Shakeapeare Parallax Devices Charaet arlaiftt ions If. DRMSATIC A® STOISTIC DEVICES CP THE HEVtSCIt PfcSjS. • . .58 ?b® Cborua In Bm&m and Rmm$® Play®' Innovation of tba Dunb Show and Play-withli*- t be-Play Art in Seaeea and Revenge Playa V. CONCLTISIOB 85 B1BLI0SMPB1 91 cmrtm i THE VOBTJE m Stmck, 1570*1000 I» this thesis mn attempt will be sade to tra©# briefly the revival of Seneoart tragedy from 1570 to the end of the sixteenth eenttiry through s«®te of the earlier translations, adaptations, end imitations, and to evaluate the stgnlfl* mm* of the final evolution of eueh works into the BUssabethan tragedy of revenge. -

EMPRESAS DE TRANSPORTE DE MERCADORIAS - NACIONAL / INTERNACIONAL E EXCLUSIVAMENTE NACIONAL - Por Ordem Alfabética Das Empresas

EMPRESAS DE TRANSPORTE DE MERCADORIAS - NACIONAL / INTERNACIONAL E EXCLUSIVAMENTE NACIONAL - Por ordem alfabética das empresas Nº DESIGNAÇÃO DA EMPRESA CONCELHO MORADA LOCALIDADE CÓDIGO E LOCALIDADE POSTAL ÂMBITO ALV./L.COM. 10 DE JULHO - TRANSPORTES, LDA. VILA FRANCA DE XIRA PRAÇA FRANCISCO CÂNCIO, Nº 38, 4º B 2600-535 ALHANDRA NAC./INT. 668824 100 DEMORAS - TRANSPORTES DE MERCADORIAS, SINTRA RUA DAS INDÚSTRIAS, Nº 12 QUELUZ DE BAIXO 2745-838 QUELUZ NAC. 664872 LDA. 101% EXPRESS, ENTREGAS RÁPIDAS, LDA. PORTO RUA JOÃO MARTINS BRANCO, 41-3º ESQº 4150-431 PORTO NAC./INT. 663409 10TAKLÉGUAS - UNIPESSOAL, LDA. ARRUDA DOS VINHOS LARGO DO ALTO, Nº. 1 2630-539 SANTIAGO DOS VELHOS NAC./INT. 666535 2 AB - COMÉRCIO E SERVIÇOS DE EQUIPAMENTOS, ALCOBAÇA ESTRADA NACIONAL Nº 1 2475-027 BENEDITA NAC. 658416 LDA. 2 AB II - PEÇAS AUTO, LDA. ALCOBAÇA ESTRADA NACIONAL Nº 1, KM 82 2476-901 BENEDITA NAC. 668417 2FT - TRANSPORTES FERNANDO & FILIPE, LDA. ÁGUEDA RUA DE VALE D'ERVA, PAREDES 3750-314 ÁGUEDA NAC./INT. 663630 2M - TRANS-ALUGUER E VENDA DE EQUIPAMENTOS PENAFIEL RUA DO CARVALHO DE BAIXO, Nº 19 4575-264 OLDRÕES NAC./INT. 669027 INDUSTRIAIS, LDA. 301 TRANS, UNIPESSOAL, LDA. GONDOMAR RUA DR. SALGADO ZENHA, ENTRADA 17, SALA 2 4435-219 RIO TINTO NAC./INT. 667330 RUA JOSÉ LOPES CASQUILHO, CONDOMÍNIO 321 JUNK SERVICES, LDA. LOURES MURTEIRA 2670-550 LOURES NAC. 669514 CERRADO DA EIRA, VIVENDA 2 360 TRANS - TRANSPORTES E REBOQUES, LDA. GOUVEIA RUA DO SOITO, N.º 5 6290-241 PAÇOS DA SERRA NAC./INT. 667667 365 DIAS - TRANSPORTES, LDA. LOULÉ RUA MOUZINHO DE ALBUQUERQUE, NºS. 33 E 35 LOULÉ 8100-707 LOULÉ NAC./INT. -

Abstract Stuart Suits and Smocks

ABSTRACT STUART SUITS AND SMOCKS: DRESS, IDENTITY, AND THE POLITICS OF DISPLAY IN THE LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH COURT by Emilie M. Brinkman This thesis centers on the language of dress and the politics of display during the late Stuart dynasty (1660–88). In the late Stuart courts, fashion and material possessions became an extension of one’s identity. As such, this study examines how elite Englishmen and women viewed themselves, and others, through their clothing on the eve of Britain’s birth in response to critical moments of identity crisis during the Restoration period. Whitehall courtiers and London gentility utilized their physical appearance, specifically their clothing, accoutrements, and furnishings, to send messages in order to define themselves, particularly their “Englishness,” in response to numerous unresolved issues of identity. Therefore, this thesis argues that the roots of English national character were evident in the courts of Charles II and James II as a portion of the English population bolstered together in defiance of the French culture that pervaded late seventeenth-century England. STUART SUITS AND SMOCKS: DRESS, IDENTITY, AND THE POLITICS OF DISPLAY IN THE LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH COURT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Emilie M. Brinkman Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2013 Advisor ______________________ P. Renée Baernstein, PhD Reader ______________________ Andrew Cayton, PhD Reader ______________________ Katharine Gillespie, PhD TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. The Character of Clothes 12 III. Diplomatic Dress 23 IV. Gendered Garb 36 V. -

Final Performance Evaluation of the Fararano Development Food Security Activity in Madagascar

Final Performance Evaluation of the Fararano Development Food Security Activity in Madagascar March 2020 |Volume II – Annexes J, K, L IMPEL | Implementer-Led Evaluation & Learning Associate Award ABOUT IMPEL The Implementer-Led Evaluation & Learning Associate Award works to improve the design and implementation of Food for Peace (FFP)-funded development food security activities (DFSAs) through implementer-led evaluations and knowledge sharing. Funded by the USAID Office of Food for Peace (FFP), the Implementer-Led Evaluation & Learning Associate Award will gather information and knowledge in order to measure performance of DFSAs, strengthen accountability, and improve guidance and policy. This information will help the food security community of practice and USAID to design projects and modify existing projects in ways that bolster performance, efficiency and effectiveness. The Implementer-Led Evaluation & Learning Associate Award is a two-year activity (2019-2021) implemented by Save the Children (lead), TANGO International, and Tulane University in Haiti, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, Malawi, Nepal, and Zimbabwe. RECOMMENDED CITATION IMPEL. (2020). Final Performance Evaluation of the Fararano Development Food Security Activity in Madagascar (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: The Implementer-Led Evaluation & Learning Associate Award PHOTO CREDITS Three-year-old child, at home in Mangily village (Toliara II District), after recovering from moderate acute malnutrition thanks to support from the Fararano Project. Photo by Heidi Yanulis for CRS. DISCLAIMER This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the Implementer-Led Evaluation & Learning (IMPEL) award and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. -

Fluoride: the Natural State of Water

Acid + Sugar = Trouble Did you know? Fluoride: The Nutrition Facts Regular Nutrition Facts Serv. Size, 1 Can (regular) pop Serv. Size, 1 Can (diet) contains • Amount per Serving Amount per Serving Soft drink companies pay school districts both sugar large royalties in exchange for the right to Calories 140 and acid Calories 0 Total Fat 0grams that can Total Fat 0 grams Natural State Sodium 50 mg Sodium 40 mg market their product exclusively in the lead to Total Carb 39 grams Total Carb 0 grams schools, which in turn boosts pop sales Sugars 39 grams tooth Protein 0 grams Protein 0 grams decay. among kids. Although Carbonated Water, diet pop is Caramel Color, Aspartame, Carbonated Water, High Phosphoric Acid, of Water • sugar free, American consumption of soft drinks, Fructose Corn Syrup, Potassium Benzoate (to it still including carbonated beverages, fruit and/or Sucrose, Caramel protect taste) Natural Color, Phosphoric Acid, contains Flavors, Citric Acid, juice and sports drinks increased by 500 Natural Flavors, Caffeine harmful Caffeine percent in the past 50 years. acid Acid Amount* Sugar Amount** • Americans drank more than 53 gallons of (low number = teaspoons soft drinks per person in 2000. This bad for teeth) per 12 ounces amount surpassed all other beverages. (1 can) One of every four beverages consumed Pure Water 7.00 0.0 today is a soft drink, which means other, Barq’s 4.61 10.7 more nutritious beverages are being Diet 7Up 3.67 0.0 displaced from the diet. Sprite 3.42 9.0 • Today, one fifth of all 1- to 2-year-old Diet Dr. -

Understanding Others: Cultural and Cross-Cultural Studies and the Teaching of Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 352 649 CS 213 590 AUTHOR Trimmer, Joseph, Ed.; Warnock, Tilly, Ed. TITLE Understanding Others: Cultural and Cross-Cultural Studies and the Teaching of Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5562-6 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 269p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 55626-0015; $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Awareness; Cultural Context; Cultural Differences; Higher Education; *Literary Criticism; *Literature Appreciation; *Multicultural Education IDENTIFIERS Literature in Translation ABSTRACT This book of essays offers perspectives for college teachers facing the perplexities of today's focus on cultural issues in literature programs. The book presents ideas from 19 scholars and teachers relating to theories of culture-oriented criticism and teaching, contexts for these activities, and specific, culture-focused texts significant for college courses. The articles and their authors are as follows:(1) "Cultural Criticism: Past and Present" (Mary Poovey);(2) "Genre as a Social Institution" (James F. Slevin);(3) "Teaching Multicultural Literature" (Reed Way Dasenbrock);(4) "Translation as a Method for Cross-Cultural Teaching" (Anuradha Dingwaney and Carol Maier);(5) "Teaching in the Television Culture" (Judith Scot-Smith Girgus and Cecelia Tichi);(6) "Multicultural Teaching: It's an Inside Job" (Mary C. Savage); (7) "Chicana Feminism: In the Tracks of 'the' Native Woman" (Norma Alarcon);(8) "Current African American Literary Theory: Review and Projections" (Reginald Martin);(9) "Talking across Cultures" (Robert S. -

SERIES 4400, 4500/4600/LCD ICE Beverage Dispenser MODELS 22, 30

SERIES 4400, 4500/4600/LCD ICE BEvERAgE DISpENSER MODELS 22, 30 Operations Manual LANCER 6655 Lancer Blvd. San Antonio, Texas 78219 To order parts, call Customer Service: 800-729-1500 Warranty/Technical Support: 800-729-1550 Email: [email protected] www.lancercorp.com ISO 9001:2000 Quality System Certified Manual PN: 28-0255/11 “Lancer” is the registered trademark of Lancer © 2011 by Lancer, all rights reserved. OCT 2011 FOR QUALIFIED INSTALLER ONLY IBD 4500/4600/LCD TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE IBD 4500/4600/LCD SERIES..........................................................................................................................3 pRE-INSTALLATION CHECKLIST.......................................................................................................................................3 SpECIFICATIONS IBD 22.............................................................................................................................................................................4 IBD 30.............................................................................................................................................................................5 gUIDELINES/SAFETY/CAUTIONS ......................................................................................................................................6 ELECTRICAL WARNING ...............................................................................................................................................6 CARBON DIOXIDE WARNING ......................................................................................................................................7