Television News Coverage of the CIA Drone Program Darcy Bedgio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

ENTREPRENEURIAL EDGE Page 10

SPRING 2015 MAGAZINEM A G A Z I N E ENTREPRENEURIAL EDGE Page 10 HONOR ROLL OF DONORS Page 37 70505_co2.indd 1 3/31/15 7:10 PM 70505_co2.indd 2 3/31/15 7:10 PM Spring 2015, Volume 12, Number 01 CONTENTS CABRINI Magazine is published by the Marketing and Communications Office. 10 Feature: Entrepreneurial Edge Editor Cabrini alumni share stories Megan Maccherone of starting their own business Writers/Contributors Christopher Grosso Nicholas Guldin ’12 David Howell Lori Iannella ’06 Core Values Megan Maccherone 18 Rachel McCarter Highlights and updates of Cabrini’s Katie Aiken Ritter work for the greater good Photography Discovery Channel Nicholas Guldin ’12 Linda Johnson Kelly & Massa Jim Roese 37 2013-2014 Honor Roll of Donors Stuart Sternberg A special report honoring our donors Matthew Wright President Donald Taylor, Ph.D. Cabinet Beverly Bryde, Ed.D., Dean, Education Celia Cameron Vice President, Marketing & DEPARTMENTS Communications Brian Eury 2 Calendar of Events Vice President, Community Development & External Relations 3 From The President Jeff Gingerich, Ph.D. Interim Provost & Vice-President, 4 News On Campus Academic Affairs Mary Harris, Ph.D., 22 Athletics Interim Dean, Academic Affairs Christine Lysionek, Ph.D. 24 Alumni News Vice President, Student Life Eric Olson, C.P.A. 33 Class Notes Vice President, Finance/Treasurer Etc. Robert Reese 36 Vice President, Enrollment Pierce Scholars’ Food Recovery Management Susan Rohanna Human Resources Director George Stroud, Ed.D. On the Cover: Dean of Students Dave Perillo ‘00 prepares his talk to Cabrini design Marguerite Weber, D.A. Vice President, Adult & Professional students about being a freelance illustrator. -

Cultural Convergence Insights Into the Behavior of Misinformation Networks on Twitter

Cultural Convergence Insights into the behavior of misinformation networks on Twitter Liz McQuillan, Erin McAweeney, Alicia Bargar, Alex Ruch Graphika, Inc. {[email protected]} Abstract Crocco et al., 2002) – from tearing down 5G infrastructure based on a conspiracy theory (Chan How can the birth and evolution of ideas and et al., 2020) to ingesting harmful substances communities in a network be studied over misrepresented as “miracle cures” (O’Laughlin, time? We use a multimodal pipeline, 2020). Continuous downplaying of the virus by consisting of network mapping, topic influential people likely contributed to the modeling, bridging centrality, and divergence climbing US mortality and morbidity rate early in to analyze Twitter data surrounding the the year (Bursztyn et al., 2020). COVID-19 pandemic. We use network Disinformation researchers have noted this mapping to detect accounts creating content surrounding COVID-19, then Latent unprecedented ‘infodemic’ (Smith et al., 2020) Dirichlet Allocation to extract topics, and and confluence of narratives. Understanding how bridging centrality to identify topical and actors shape information through networks, non-topical bridges, before examining the particularly during crises like COVID-19, may distribution of each topic and bridge over enable health experts to provide updates and fact- time and applying Jensen-Shannon checking resources more effectively. Common divergence of topic distributions to show approaches to this, like tracking the volume of communities that are converging in their indicators like hashtags, fail to assess deeper topical narratives. ideologies shared between communities or how those ideologies spread to culturally distant 1 Introduction communities. In contrast, our multimodal analysis combines network science and natural language The COVID-19 pandemic fostered an processing to analyze the evolution of semantic, information ecosystem rife with health mis- and user-generated, content about COVID-19 over disinformation. -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

Ellen L. Weintraub

2/5/2020 FEC | Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub Home › About the FEC › Leadership and Structure › All Commissioners › Ellen L. Weintraub Ellen L. Weintraub Democrat Currently serving CONTACT Email [email protected] Twitter @EllenLWeintraub Biography Ellen L. Weintraub (@EllenLWeintraub) has served as a commissioner on the U.S. Federal Election Commission since 2002 and chaired it for the third time in 2019. During her tenure, Weintraub has served as a consistent voice for meaningful campaign-finance law enforcement and robust disclosure. She believes that strong and fair regulation of money in politics is important to prevent corruption and maintain the faith of the American people in their democracy. https://www.fec.gov/about/leadership-and-structure/ellen-l-weintraub/ 1/23 2/5/2020 FEC | Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub Weintraub sounded the alarm early–and continues to do so–regarding the potential for corporate and “dark-money” spending to become a vehicle for foreign influence in our elections. Weintraub is a native New Yorker with degrees from Yale College and Harvard Law School. Prior to her appointment to the FEC, Weintraub was Of Counsel to the Political Law Group of Perkins Coie LLP and Counsel to the House Ethics Committee. Top items The State of the Federal Election Commission, 2019 End of Year Report, December 20, 2019 The Law of Internet Communication Disclaimers, December 18, 2019 "Don’t abolish political ads on social media. Stop microtargeting." Washington Post, November 1, 2019 The State of the Federal Election -

Sunday Morning, March 6

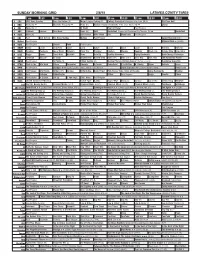

SUNDAY MORNING, MARCH 6 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (cc) Paid NBA Countdown NBA Basketball Chicago Bulls at Miami Heat. (Live) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (Live) (cc) Paid Tails of Abbygail CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation College Basketball Kentucky at Tennessee. (Live) (cc) College Basketball 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (cc) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) NHL Hockey Philadelphia Flyers at New York Rangers. (Live) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Curious George Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Clash: Encounters of NOVA The Pluto Files. People’s 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Bears and Wolves. (cc) (TVPG) opinions about Pluto. (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Paid Memories of Me ★★ (‘88) Billy Crystal, Alan King. A young surgeon NASCAR Racing 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) goes to L.A. to reconcile with his father. ‘PG-13’ (1:43) 5:00 Inspiration Ministry Camp- Turning Point Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 meeting (Cont’d) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Spring Praise-A-Thon 24/KNMT 20 20 Paid Outlook Portland In Touch With Dr. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Soledad O'brien

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Soledad O'Brien Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: O’Brien, Soledad, 1966- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Soledad O'Brien, Dates: February 21, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 6 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:42:12). Description: Abstract: Broadcast journalist Soledad O'Brien (1966 - ) founded the Starfish Media Group, and anchored national television news programs like NBC’s The Site and American Morning, and CNN’s In America. O'Brien was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on February 21, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_055 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Broadcast journalist Soledad O’Brien was born on September 19, 1966 in Saint James, New York. Her father, Edward, was a mechanical engineering professor; her mother, Estela, a French and English teacher. O’Brien graduated from Smithtown High School East in 1984, and went on to attend Harvard University from 1984 to 1988, but did not graduate until 2000, when she received her B.A. degree in English and American literature. In 1989, O’Brien began her career at KISS-FM in Boston, Massachusetts as a reporter for the medical talk show Second Opinion and of Health Week in Review. In 1990, she was hired as an associate producer and news writer for Boston’s WBZ-TV station. O’Brien then worked at NBC News in New York City in 1991, as a field producer for Nightly News and Today, before being hired at San Francisco’s NBC affiliate KRON in 1993, where she worked as a reporter and bureau chief and co-hosted the Discovery Channel’s The Know Zone. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

May 4, 2012 VIA REGULAR MAIL A.T. Smith Deputy Director U.S. Secret

May 4, 2012 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, Va. 22209-2211 VIA REGULAR MAIL (703) 807-2100 www.rcfp.org A.T. Smith Lucy A. Dalglish Executive Director Deputy Director U.S. Secret Service STEERING COMMITTEE Communications Center SCOTT APPLEWHITE 245 Murray Lane, S.W. The Associated Press WOLF BLITZER Building T-5 CNN Washington, D.C. 20223 DAVID BOARDMAN Seattle Times CHIP BOK Creators Syndicate Freedom of Information Act Appeal ERIKA BOLSTAD Expedited Processing Requested for File Nos. 20120546-20120559 McClatchy Newspapers JESS BRAVIN The Wall Street Journal MICHAEL DUFFY Time Dear Mr. Smith: RICHARD S. DUNHAM Houston Chronicle This is an appeal of a denial of expedited processing under the Freedom of ASHLEA EBELING Forbes Magazine Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(E)(i)(I) (“FOIA”), and 6 C.F.R., FRED GRAHAM InSession Chapter 1, Part 5 § 5.5. On March 27, 2012, I made a FOIA request to the JOHN C. HENRY Department of Homeland Security for expedited processing of the following: Freelance NAT HENTOFF United Media Newspaper Syndicate 1. Perfected, pending FOIA request letters submitted to your office on DAHLIA LITHWICK Slate the dates provided below, which were listed on the Securities and Exchange TONY MAURO Commission’s 2011 Annual FOIA report as being included in the “10 Oldest National Law Journal Pending Perfected FOIA Requests:”1 DOYLE MCMANUS Los Angeles Times 11/30/2005 ANDREA MITCHELL NBC News 12/2/2005 MAGGIE MULVIHILL 12/2/2005 New England Center for Investigative Reporting BILL NICHOLS 1/19/2006 Politico SANDRA PEDDIE 1/19/2006 Newsday 1/19/2006 DANA PRIEST The Washington Post 1/19/2006 DAN RATHER HD Net 2. -

The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-5-2018 News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Higgins-Dobney, Carey Lynne, "News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4410. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6307 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. News Work: The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting by Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Studies Dissertation Committee: Gerald Sussman, Chair Greg Schrock Priya Kapoor José Padín Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney News Work i Abstract By virtue of their broadcast licenses, local television stations in the United States are bound to serve in the public interest of their community audiences. As federal regulations of those stations loosen and fewer owners increase their holdings across the country, however, local community needs are subjugated by corporate fiduciary responsibilities. Business practices reveal rampant consolidation of ownership, newsroom job description convergence, skilled human labor replaced by computer automation, and economically-driven downsizings, all in the name of profit. -

Programming Notes - First Read

Programming notes - First Read Hotmail More TODAY Nightly News Rock Center Meet the Press Dateline msnbc Breaking News EveryBlock Newsvine Account ▾ Home US World Politics Business Sports Entertainment Health Tech & science Travel Local Weather Advertise | AdChoices Recommended: Recommended: Recommended: 3 Recommended: First Thoughts: My, VIDEO: The Week remaining First Thoughts: How New iPads are Selling my, Myanmar That Was: Gifts, undecided House Rebuilding time for Under $40 fiscal cliff, and races verbal fisticuffs How Cruise Lines Fill All Those Unsold Cruise Cabins What Happens When You Take a Testosterone The first place for news and analysis from the NBC News Political Unit. Follow us on Supplement Twitter. ↓ About this blog ↓ Archives E-mail updates Follow on Twitter Subscribe to RSS Like 34k 1 comment Recommend 3 0 older3 Programming notes newer days ago *** Friday's "The Daily Rundown" line-up with guest host Luke Russert: NBC's Kelly O'Donnell on Petraeus' testimony… NBC's Ayman Mohyeldin live in Gaza… one of us (!!!) with more on the Republican reaction to Romney… NBC's Mike Viqueira on today's White House meeting on the fiscal cliff and The Economist's Greg Ip and National Journal's Jim Tankersley on the "what ifs" surrounding the cliff… New NRCC Chairman Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) on the House GOP's road forward… Democratic strategist Doug Thornell, Roll Call's David Drucker and the New York Times' Jackie Calmes on how the next round of negotiations could be different (or all too similar) to the last time. Advertise | AdChoices *** Friday’s “Jansing & How to Improve Memory E-Cigarettes Exposed: Stony Brook Co.” line-up: MSNBC’s Chris with Scientifically Designed The E-Cigarette craze is sweeping the country. -

Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Hopper, Hannah, "Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3402. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3402 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Media and Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Brand and Media Strategy _____________________ by Hannah Hopper May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Susan E. Waters, Chair Dr. Melanie Richards Dr. Phyllis Thompson Keywords: Political Journalist, Twitter, Agenda Setting, Framing, Gatekeeping, Feminist Political Theory, Political Polarization, Presidential Debate, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump ABSTRACT Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate by Hannah Hopper Past research shows that journalists are gatekeepers to information the public seeks.