Pre-Revolutionary Action by Orange County Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

The Origins of a Free Press in Prerevolutionary Virginia: Creating

Dedication To my late father, Curtis Gordon Mellen, who taught me that who we are is not decided by the advantages or tragedies that are thrown our way, but rather by how we deal with them. Table of Contents Foreword by David Waldstreicher....................................................................................i Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................iii Chapter 1 Prologue: Culture of Deference ...................................................................................1 Chapter 2 Print Culture in the Early Chesapeake Region...........................................................13 A Limited Print Culture.........................................................................................14 Print Culture Broadens ...........................................................................................28 Chapter 3 Chesapeake Newspapers and Expanding Civic Discourse, 1728-1764.......................57 Early Newspaper Form...........................................................................................58 Changes: Discourse Increases and Broadens ..............................................................76 Chapter 4 The Colonial Chesapeake Almanac: Revolutionary “Agent of Change” ...................97 The “Almanacks”.....................................................................................................99 Chapter 5 Women, Print, and Discourse .................................................................................133 -

The Appellate Question: a Comparative Analysis of Supreme Courts of Appeal in Virginia and Louisiana, 1776-1840

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 The appellate question: A comparative analysis of supreme courts of appeal in Virginia and Louisiana, 1776-1840 Mark F. Fernandez College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Law Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Fernandez, Mark F., "The appellate question: A comparative analysis of supreme courts of appeal in Virginia and Louisiana, 1776-1840" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623810. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jtfj-2738 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if _ unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

The Early Political Career of Robert Carter Nicholas, 1728-1769

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1961 The Early Political Career of Robert Carter Nicholas, 1728-1769 William J. Lescure College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lescure, William J., "The Early Political Career of Robert Carter Nicholas, 1728-1769" (1961). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624522. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-df2m-r775 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. tug nmr mmmm mmm m eobot cahter kxgrous X728—1769 4 th e sis FresoBted to the Facility of the DepartmeBt of History fho Collage of William and Mary 2b firg in ia M Fartisl Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by William las cure January 1961 " im o w > .ffeie'tllaei® i s siafrmitted in p a rtia l fu lfillm e n t o f ; ’Ik®, raq&ireiaenta fo r the degree o f ! . .• • i k t ■ :Haetearef Jlrts :" '' f' .. Agjgramd* $m m rp 19&ls * 1%; 0 . \J ijJlU u^ W ' i^ ln ^ W iM m W M o i, TS£"®7 & $ i r u n u A J %&mmm H* famer^ fh , B. ■ ^ X 4 X n ^ t i J f. -

The Stamp Act and Methods of Protest

Page 33 Chapter 8 The Stamp Act and Methods of Protest espite the many arguments made against it, the Stamp Act was passed and scheduled to be enforced on November 1, 1765. The colonists found ever more vigorous and violent ways to D protest the Act. In Virginia, a tall backwoods lawyer, Patrick Henry, made a fiery speech and pushed five resolutions through the Virginia Assembly. In Boston, an angry mob inspired by Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty destroyed property belonging to a man rumored to be a Stamp agent and to Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In New York, delegates from nine colonies, sitting as the Stamp Act Congress, petitioned the King and Parliament for repeal. In Philadelphia, New York, and other seaport towns, merchants pledged not to buy or sell British goods until the hated stamp tax was repealed. This storm of resistance and protest eventually had the desired effect. Stamp sgents hastily resigned their Commissions and not a single stamp was ever sold in the colonies. Meanwhile, British merchants petitioned Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. In 1766, the law was repealed but replaced with the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had the right to make laws binding on the colonies "in all cases whatsoever." The methods used to protest the Stamp Act raised issues concerning the use of illegal and violent protest, which are considered in this chapter. May: Patrick Henry and the Virginia Resolutions Patrick Henry had been a member of Virginia's House of Burgess (Assembly) for exactly nine days as the May session was drawing to a close. -

Albemarle County in Virginia

^^m ITD ^ ^/-^7^ Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.arGhive.org/details/albemarlecountyiOOwood ALBEMARLE COUNTY IN VIIIGIMIA Giving some account of wHat it -was by nature, of \srHat it was made by man, and of some of tbe men wHo made it. By Rev. Edgar Woods " It is a solemn and to\acKing reflection, perpetually recurring. oy tHe -weaKness and insignificance of man, tHat -wKile His generations pass a-way into oblivion, -with all tKeir toils and ambitions, nature Holds on Her unvarying course, and pours out Her streams and rene-ws Her forests -witH undecaying activity, regardless of tHe fate of Her proud and perisHable Sovereign.**—^e/frey. E.NEW YORK .Lie LIBRARY rs526390 Copyright 1901 by Edgar Woods. • -• THE MicHiE Company, Printers, Charlottesville, Va. 1901. PREFACE. An examination of the records of the county for some in- formation, awakened curiosity in regard to its early settle- ment, and gradually led to a more extensive search. The fruits of this labor, it was thought, might be worthy of notice, and productive of pleasure, on a wider scale. There is a strong desire in most men to know who were their forefathers, whence they came, where they lived, and how they were occupied during their earthly sojourn. This desire is natural, apart from the requirements of business, or the promptings of vanity. The same inquisitiveness is felt in regard to places. Who first entered the farms that checker the surrounding landscape, cut down the forests that once covered it, and built the habitations scattered over its bosom? With the young, who are absorbed in the engagements of the present and the hopes of the future, this feeling may not act with much energy ; but as they advance in life, their thoughts turn back with growing persistency to the past, and they begin to start questions which perhaps there is no means of answering. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Harper's, 'Is there Virtue in Profit: Reconsidering the Morality of Capitalism', vol. 273 (December 1986 ), 38. 2. Joyce Appleby, Capitalism and a New Social Order: The Republican Vision of the 1790s (New York, 1984), 25-50. 3. John M. McCusker & Russell R. Menard, The Economy of British America, 1607-1789 (Chapel Hill, 1985), 71. On the importance of overseas trade to individuals' income in the colonies see Alice Hansen Jones, Wealth of a Nation: The American Colonies on the Eve of the Revolution (New York, 1980), 65-66. 4. James A. Field Jr., 'All Economists, All Diplomats', in William H. Becker and Samuel F. Wells Jr., eds, Economic and World Power (New York, 1989), 1. 5. Jefferson to James Madison, January 30, 1787; to William Stephen Smith, November 13, 1787, Julian P. Boyd et al. eds, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 24 vols to date (Princeton, 1950- , hereafter Jefferson Papers), XI, 93, XII, 356. 6. Richard K. Mathews, The Radical Politics of Thomas Jefferson: A Revisionist View (Lawrence, Kansas, 1984), 122. 7. James Madison toN. P. Trist, May 1832, Gillard Hunted., The Writings of James Madison 9 vols (New York, 1900-1910) IX, 479. 8. Dumas Malone, Jefferson and his Time, 6 vols (Boston 1948-1981), vol. 1: Jefferson the Virginian vol. 2: Jefferson and the Rights of Man; vol. 3: Jefferson and the Ordeal Liberty; vol. 4: Jefferson the President: First Term, 1801-1805; vol. 5: Jefferson the President: Second Term, 1805-1809; vol. 6: The Sage of Monticello. 9. Merrill Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the new Nation: A Biography (New York, 1970); idem, The Jefferson ]mage in the American Mind (New York, 1960). -

The Nelson Family and Commercial Resistance in Yorktown, Virginia 1769-1771

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 7-2012 "The Spirit of Association": The Nelson Family and Commercial Resistance in Yorktown, Virginia 1769-1771 Eric F. Ames College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ames, Eric F., ""The Spirit of Association": The Nelson Family and Commercial Resistance in Yorktown, Virginia 1769-1771" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 478. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/478 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE SPIRIT OF ASSOCIATION”: THE NELSON FAMILY AND COMMERCIAL RESISTANCE IN YORKTOWN, VIRGINIA 1769-1771 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Eric F. Ames Accepted For____________________ _________________________ Director ________________________________ ________________________________ Acknowledgments I would first like to acknowledge my adviser, Prof. Julie Richter, for her assistance and guidance on this project, and for providing feedback on the drafts of this thesis. I would also like to thank Profs. Paul S. Davies and Scott R. Nelson for agreeing to sit on the committee that assessed this thesis. I would like to also acknowledge my family, as well as countless other members of the Tribe who contributed their patience and support during the duration of this project. -

Fond Du Lac Treaty Portraits: 1826

Fond du Lac Treaty Portraits: 1826 RICHARD E. NELSON Duluth, Minnesota The story of the Fond du Lac Treaty portraits began on the St. Louis River at a site near the present city of Duluth with these words: Whereas a treaty between the United States of America and the Chippeway tribe of Indians, was made and concluded on the fifth day of August, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-six, at the Fond du Lac of Lake Superior, in the territory of Michigan, by Commissioners on the part of the United States, and certain Chiefs and Warriors of the said tribe . (McKenney 1959:479) The location was memorialized by a monument erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution, Duluth, Minnesota, on November 21, 1922, which reads: Fond du Lac, Minnesota. Site of an Ojibway village from the earliest known pe riod. Daniel Greysolon Sieur de Lhut was here in 1679. Astor's American Fur Company established a trading post on this spot about 1817. First Ojibway treaty in Minnesota made here in 1826. The report of the treaty is recorded in Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes, of the Character and Customs of the Chippeway Indians, and of Incidents Connected with the Treaty of Fond du Lac written by Thomas K. McKenney in the form of letters to Secretary of War James Barbour in Washington and first published in 1827. McKenney was the head of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. In May of 1826 he and Lewis Cass, the governor of the Michigan Territory, were appointed by President John Quincy Adams to conclude a major treaty at Fond du Lac. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

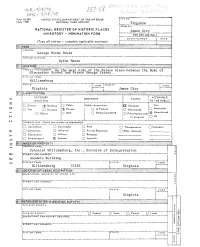

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER Dal"E

_, i.. t, 'I . •I · Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF fHE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NA Tl ON Al PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY, NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DAl"E COMMON: George Wythe House ANOI OR HISTORIC, Wythe House ,__ -·-· -·-:-",-,_:,v.•.,'.•.'c:'. •i•:?-,•· \/:c+i,)"!;)'.(' :{/(;".;.\p; LC '<it\:\ STREET ANo NUMBER: On the west side of the Palace Green between the Duke of Gloucester Street and Prince George Street. --CITY -OR-------------------------------------------------1 TOWN: Williamsburg STATE COOE COUNTY · CODE Virginia •--·-:•, .,. .. __ . 1):\;¢tAs~iFiC:.Xi'tqif :_/</ >:Y /- :· T'•• .. _.L: <> , <f %%\Xfr ;?\ '" _.,..,. ., ....., .___ _ : -:-: : .•:-. ··:::-:;:.':• .;;(:;}'.)\:;:.~:y CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z D District rn Bui /ding D Public I Public Acquisitil>n: n Occupiod Yes; 0 Restricted D Sile 0 Structu,e rn PriYate 0 In Process 0 Unoccupied D Both 0 Beir,g Con~id&red Unrestricted 0 Object 0 0 Pr&s&rvation work \ ixJ 1- in progr&ss \ D No u PRESENT USE (CJ>eck on~ or More BS Appropr/eto) D Agricultura l D Government 0 Pork 0 Trol'\sportatl on 0 Comm&nts 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Pr/vote Residenco 0 Other ($pt,c/!y) D Educational D M;J itary 0 R&ligiou• D Entorta i rimenf ~ Museum 0 Scientific OWNEA' s NAME: -I"' ), Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Division of Interpretation -I "1 w Sl"AEET AND NUMBER: UJ Goodwin Building CITY OR TOWN : STATE< CODE Willi4msburg 23185 Virginia ~~~l~'OF'.t{fi~Wtl'.]~~p'rtl&:i'.:L9~/ --._.