Language and Sexuality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queer Definitions

! ! The Amherst College Queer Resource Center's Terms, Definitions, and Labels Compiled and adapted by David Huante '16 QRC Activities Coordinator ! ! Terminology is important. The words we use, and how we use them, can be very powerful. Knowing and understanding the meaning of the words we use improves communication and helps prevent misunderstandings. The following terms are not absolutely-defined. Rather, they provide a starting point for conversations. As always, listening is the key to understanding. Every thorough discussion about the queer community starts with terminology. Some of this terminology may be confusing or surprising; please do not hesitate to ask for clarification. This is a partial list of terms you may encounter. New language and terms emerge as our understanding of these topics changes and evolves. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Affectional (Romantic) Orientation Ally Refers to variations in object of An individual whose attitudes and emotional and sexual attraction. The term behavior are supportive and affirming is preferred by some over “sexual of all genders and sexual orientations orientation” because it indicates that the and who is active in combating feelings and commitments involved are homophobia, transphobia, not solely (or even primarily, for some heterosexism, and cissexism both people) sexual. The term stresses the personally and institutionally. affective emotional component of attractions and relationships, regardless of orientation. Androgyny Asexual Displaying physical and social A person who doesn't experience characteristics identified in this culture sexual attraction or who has low or no as both feminine and masculine to the interest in sexual activity. Unlike degree that the person’s outward celibacy, an action that people choose, appearance and mannerisms make it asexuality is a sexual identity. -

2019-03-17 5C8e1290421a2 Gagafeminism.Pdf

OTHER BOOKS BY J. JACK HALBERSTAM Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters Posthuman Bodies. Coedited with Ira Livingston Female Masculinity The Drag King Book. With Del LaGrace Volcano In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives The Queer Art of Failure OTHER BOOKS IN THE QUEER IDEAS SERIES Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States by Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock God vs. Gay? The Religious Case for Equality by Jay Michaelson Beyond (Straight and Gay) Marriage: Valuing All Families under the Law by Nancy D. Polikoff From the Closet to the Courtroom: Five LGBT Rights Lawsuits That Have Changed Our Nation by Carlos A. Ball OTHER BOOKS IN THE QUEER ACTION SERIES Come Out and Win: Organizing Yourself, Your Community, and Your World by Sue Hyde Out Law: What LGBT Youth Should Know about Their Legal Rights by Lisa Keen For Maca CONTENTS A NOTE FROM THE SERIES EDITOR 1 PREFACE Going Gaga 4 INTRODUCTION 11 ONE Gaga Feminism for Beginners 24 TWO Gaga Genders 64 THREE Gaga Sexualities: The End of Normal 112 FOUR Gaga Relations: The End of Marriage 154 FIVE Gaga Manifesto 206 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 233 NOTES 235 A NOTE FROM THE SERIES EDITOR The American lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer movement has never been only a movement about civil rights. From its beginnings in the 1950s, groups like the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis understood the power of popular culture. The gay liberation movement of the early 1970s understood that the way to political power was through popular culture. -

Friendship Between Gay Men and Heterosexual Women: an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

Friendship between Gay Men and Heterosexual Women: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Tina Grigoriou Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group London South Bank University 103 Borough Road London SE1 0AA March 2004 Published by London South Bank University © Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group ISBN 1-874418-41-1 Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group Working Paper No. 5 FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN GAY MEN AND HETEROSEXUAL WOMEN: AN INTERPRETATIVE PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Tina Grigoriou Page Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Previous Research in the Field 4 Methodology 7 Analysis 12 1) Defining the friendship between gay men and heterosexual women 13 2) Friends as family 16 3) Valued characteristics of the friendship between gay men and heterosexual women 20 4) Comparing this friendship to other forms of friendship 24 5) Participants’ understanding of their social network’s perception of the friendship between them 28 Overview and Conclusions 30 References 34 Appendix 37 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Adrian Coyle, Senior Lecturer and Co-Course Director at the Department of Psychology at University of Surrey and Dr Xenia Chryssochoou, Associate Professor at the Department of Psychology at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, for their support and advice over the course of completing my MSc dissertation in Social Psychology. I am also grateful to all the participants for sharing their insights and feelings with me. 2 Introduction This working paper explores the friendship dynamics between gay men and heterosexual women. Many studies have investigated cross-sex friendships without taking into account the sexual identity of the participants (Buhrke & Fuqua, 1987; Fehr, 1996; Gaines, 1994; Monsour, 1992; O’Meara, 1989; Parker & de Vries, 1993; Reid & Fine, 1992; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988; Swain, 1992, Werking, 1997) and therefore draw conclusions about cross-sex friendships and negotiation of sexual boundaries (O’Meara, 1989; Reid and Fine, 1992; Swain, 1992). -

Gay Men's Experiences of Alaskan Society in Their Coupled Relationships Markie Louise Christianson Blumer Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 Gay men's experiences of Alaskan society in their coupled relationships Markie Louise Christianson Blumer Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Blumer, Markie Louise Christianson, "Gay men's experiences of Alaskan society in their coupled relationships" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gay men's experiences of Alaskan society in their coupled relationships by Markie Louise Christianson Blumer A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Human Development and Family Studies (Marriage and Family Therapy) Program of Study Committee: Megan J. Murphy, Major Professor Warren J. Blumenfeld Sedahlia Jasper Crase Carolyn E. Cutrona Ronald Werner-Wilson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Markie Louise Christianson Blumer, 2008. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3307096 UMI Microform 3307096 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Fag Hags' Their Badge of H

From beards to best friends, it's time to give 'fag hags' their badge of h... https://theconversation.com/from-beards-to-best-friends-its-time-to-giv... Academic rigour, journalistic flair From beards to best friends, it’s time to give ‘fag hags’ their badge of honour October 4, 2017 5.45am AEDT Eric McCormack and Debra Messing as Will and Grace. NBC/IMDB The fag hag. Never were two more scornful words so spectacularly smashed together. Stereotypes Author around the fag hag, fruitfly, fish, handbag – whatever you’d care to call her – abound. Search the Internet and you’d believe she’s a sad, overweight, trashy woman with too many cats unable to snag her own boyfriend or husband. Derision comes from queer quarters almost as often as Phoebe Hart from straight bystanders. Lecturer, Film Screen & Animation, Queensland University of Technology However, a closer examination of the history of the everyday fag hag and her references in pop culture reveals a more subversive and courageous figure. Fag hags have gone from “beards” who hide their gay friends’ sexuality to fashionable best friends epitomised by Grace in the TV series Will and Grace, which has just been revived. Further reading: Faggots, punks, and prostitutes: the evolving language of gay men It could be time to recast the moniker of “fag hag” as a badge of honour rather than a term of abuse. For the gay man, she has been protector, carer, cheerleader. For her, it is often an act of support. For the straight woman, he is a male friend that doesn’t expect more, a confidante, and just possibly the reason to become more involved in lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) activism. -

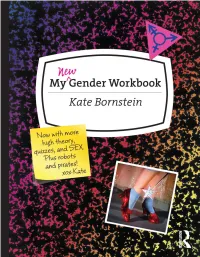

MY New Gender Workbook This Page Intentionally Left Blank N E W My Gender Workbook

my name is ________________________ and this is MY new gender workbook This page intentionally left blank N e w My Gender Workbook A Step-by-Step Guide to Achieving World Peace Through Gender Anarchy and Sex Positivity Kate Bornstein Routledge Taylor & Francis Group NEW YORK AND LONDON Second edition published 2013 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 Taylor & Francis The right of Kate Bornstein to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. First edition published by Routledge 1998 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bornstein, Kate, 1948– My new gender workbook: a step-by-step guide to achieving world peace through gender anarchy and sex positivity/ Kate Bornstein.—2nd ed. p. cm. Rev. ed. of: My gender workbook. 1998. 1. Gender identity. 2. Sex (Psychology) I. Bornstein, Kate, 1948– My gender workbook. II. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Insult and Inclusion the Term Fag Hag and Gay Male "Community"*

Insult and Inclusion The Term Fag Hag and Gay Male "Community"* DAWNE MOON, University of Chicago Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article/74/2/487/2233282 by guest on 27 September 2021 Abstract The term fag hag is normally used in gay male culture to describe a straight woman who associates with gay men. This article uses intensive interviews with gay and bisexual men to explore what the term indicates about contradictions emerging from dominant views of gender and sexual identity. Other sociological studies provide explanations for why women and gay men form relationships and how these relation- ships are negotiated. This article explores what the term, residing at the nexus of discourses of sexuality and gender, tells us about (1) how dominant, heterosexual culture's assumptions threaten gay identity and culture; (2) the tensions present within gay male culture's own dominant discourses, tensions which certain straight women create and/or highlight; and (3) the limitations imposed on political mobilization by a discourse that posits the existence of a coherent "gay community." fag-hag: heterosexual woman extensively in the company of gay men. Fag-hags fall into no single category: some are plain Janes who prefer the honest affection of homoerotic boy friends; others are on a determined crusade to show gay boys that normal coitus is not to be overlooked. A few are simply women in love with homosexual men; others determine to their chagrin that their male friends are charming but not interested sexually. No matter how you cut it, fag-hag has an ugly ring to it. -

Polari: a Sociohistorical Study of the Life and Decline of a Secret Language

Polari: A sociohistorical study of the life and decline of a secret language. Heather Taylor Undergraduate Dissertation 2007 The University of Manchester A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of B.A. Hons. in English Language and Linguistics in the University of Manchester 56951580 1 Aims & Introduction The objective of the following investigation is to examine the history of the secret in- group language Polari from a sociolinguistic perspective. This will include looking at the history and uses of this lexicon and the factors which led to its rise, and eventually to its decline. A key question posed by this investigation is the extent to which Polari survives today and the type of presence, if any, it has in contemporary gay culture. This will be done through a critical review of the available data on the topic and also by investigating the capacity in which Polari survives today (specifically focussing on whether it is present in the media and entertainment or in the internet community). Secret languages are fascinating to linguists’ curiosity, and Polari is a particularly interesting subject because of the rich tapestry of interwoven sources which build this unique lexicon, and the fact that it has been ‘off-limits’ to outsiders until very recently. The variety discovered in the lexicon is indicative of the fascinating history of Polari – a story of different itinerant groups meeting and trading lexical items along the way. It is interesting to trace how a language with its origins in the cant of thieves and travelling tradesmen, used to conceal criminal activity, came to be the exuberant carrier of gay identity in the mid-twentieth century. -

Sexuality Terms and Definitions

Sexuality Terms and Definitions Ally – An individual whose attitudes and behaviors are supportive of all sexual orientations, anti-heterosexist, and who is active in combating homophobia and heterosexism, both on a personal and institutional level. Asexual – A person who is not sexually attracted to anyone or does not have a sexual orientation. They may or may not experience romantic attraction. Bear – The most common definition of a ‘bear’ is a man who has facial/body hair, and a cuddly body. However, the word ‘bear’ means many things to different people, even within the bear movement. ‘Bear’ is often defined simply as a sense of comfort with natural masculinity and bodies. Biphobia – The fear of, discrimination against, or hatred of bisexuals, which is often times related to the current binary standard. Biphobia can be seen within the LGBTQI community, as well as society as a whole. Bisexuality – A sexual orientation in which a person has the potential to feel physically and emotionally attracted to more than one gender. Butch – A person who identifies themselves as masculine, whether it be physically, mentally or emotionally. ‘Butch’ is sometimes used as a derogatory term for lesbians, but it can also be claimed as an affirmative identity label. Coming Out – Also, “coming out of the closet” or “being out,” this term refers to the process through which a person acknowledges, accepts, and in many cases appreciates their LGBTQIA+ identity. This often involves sharing of this information with others. It is not a single event but instead a lifelong process. Down Low – To hide ones same-sex attractions and relationships while outwardly engaging in different-sex relationships. -

Adam's Ale Noun. Water. Abdabs Noun. Terror, the Frights, Nerves. Often Heard As the Screaming Abdabs. Also Very Occasionally 'H

A Adam's ale Noun. Water. abdabs Noun. Terror, the frights, nerves. Often heard as the screaming abdabs . Also very occasionally 'habdabs'. [1940s] absobloodylutely Adv. Absolutely. Abysinnia! Exclam. A jocular and intentional mispronunciation of "I'll be seeing you!" accidentally-on- Phrs. Seemingly accidental but with veiled malice or harm. purpose AC/DC Adj. Bisexual. ace (!) Adj. Excellent, wonderful. Exclam. Excellent! acid Noun. The drug LSD. Lysergic acid diethylamide. [Orig. U.S. 1960s] ackers Noun. Money. From the Egyptian akka . action man Noun. A man who participates in macho activities. Adam and Eve Verb. Believe. Cockney rhyming slang. E.g."I don't Adam and Eve it, it's not true!" aerated Adj. Over-excited. Becoming obsolete, although still heard used by older generations. Often mispronounced as aeriated . afto Noun. Afternoon. [North-west use] afty Noun. Afternoon. E.g."Are you going to watch the game this afty?" [North-west use] agony aunt Noun. A woman who provides answers to readers letters in a publication's agony column. {Informal} aggro Noun. Aggressive troublemaking, violence, aggression. Abb. of aggravation. air biscuit Noun. An expulsion of air from the anus, a fart. See 'float an air biscuit'. airhead Noun. A stupid person. [Orig. U.S.] airlocked Adj. Drunk, intoxicated. [N. Ireland use] airy-fairy Adj. Lacking in strength, insubstantial. {Informal} air guitar Noun. An imaginary guitar played by rock music fans whilst listening to their favourite tunes. aks Verb. To ask. E.g."I aksed him to move his car from the driveway." [dialect] Alan Whickers Noun. Knickers, underwear. Rhyming slang, often shortened to Alans . -

Softball) Field (Chapter 3 of the Book Between Gay and Straight: Understanding Friendship Across Sexual Orientation) Lisa M

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Faculty Publications 2001 Tales from the (Softball) Field (Chapter 3 of the book Between Gay and Straight: Understanding Friendship Across Sexual Orientation) Lisa M. Tillmann Ph.D. Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Published In Tillmann-Healy, L. M. (2001). Between Gay and Straight: Understanding Friendship Across Sexual Orientation. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Between Gay and Straight: Understanding Friendship Across Sexual Orientation1 Lisa M. Tillmann Rollins College Box 2723 Winter Park, FL 32789 [email protected] 407-646-1586 Key words: autoethnography, ethnography, qualitative research, narrative, friendship, gay men, heterosexism, homophobia 3: Tales from the (Softball) Field2 From Life to Project (and Back Again) A few weeks after Tim’s party, the fall semester begins. Since January, I’ve been writing about connections between body image, eating, and identity. During the first month of Qualitative Methods, I investigate how these relationships are performed in public life. Observing how people interact with each other and with food, I take field notes at a grocery store and some restaurants, but nothing suits my ethnographic tastes. Frustrated, I call Carolyn Ellis, the course professor and a member of my doctoral committee.