2019-03-17 5C8e1290421a2 Gagafeminism.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queer Definitions

! ! The Amherst College Queer Resource Center's Terms, Definitions, and Labels Compiled and adapted by David Huante '16 QRC Activities Coordinator ! ! Terminology is important. The words we use, and how we use them, can be very powerful. Knowing and understanding the meaning of the words we use improves communication and helps prevent misunderstandings. The following terms are not absolutely-defined. Rather, they provide a starting point for conversations. As always, listening is the key to understanding. Every thorough discussion about the queer community starts with terminology. Some of this terminology may be confusing or surprising; please do not hesitate to ask for clarification. This is a partial list of terms you may encounter. New language and terms emerge as our understanding of these topics changes and evolves. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Affectional (Romantic) Orientation Ally Refers to variations in object of An individual whose attitudes and emotional and sexual attraction. The term behavior are supportive and affirming is preferred by some over “sexual of all genders and sexual orientations orientation” because it indicates that the and who is active in combating feelings and commitments involved are homophobia, transphobia, not solely (or even primarily, for some heterosexism, and cissexism both people) sexual. The term stresses the personally and institutionally. affective emotional component of attractions and relationships, regardless of orientation. Androgyny Asexual Displaying physical and social A person who doesn't experience characteristics identified in this culture sexual attraction or who has low or no as both feminine and masculine to the interest in sexual activity. Unlike degree that the person’s outward celibacy, an action that people choose, appearance and mannerisms make it asexuality is a sexual identity. -

Friendship Between Gay Men and Heterosexual Women: an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

Friendship between Gay Men and Heterosexual Women: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Tina Grigoriou Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group London South Bank University 103 Borough Road London SE1 0AA March 2004 Published by London South Bank University © Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group ISBN 1-874418-41-1 Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group Working Paper No. 5 FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN GAY MEN AND HETEROSEXUAL WOMEN: AN INTERPRETATIVE PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Tina Grigoriou Page Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Previous Research in the Field 4 Methodology 7 Analysis 12 1) Defining the friendship between gay men and heterosexual women 13 2) Friends as family 16 3) Valued characteristics of the friendship between gay men and heterosexual women 20 4) Comparing this friendship to other forms of friendship 24 5) Participants’ understanding of their social network’s perception of the friendship between them 28 Overview and Conclusions 30 References 34 Appendix 37 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Adrian Coyle, Senior Lecturer and Co-Course Director at the Department of Psychology at University of Surrey and Dr Xenia Chryssochoou, Associate Professor at the Department of Psychology at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, for their support and advice over the course of completing my MSc dissertation in Social Psychology. I am also grateful to all the participants for sharing their insights and feelings with me. 2 Introduction This working paper explores the friendship dynamics between gay men and heterosexual women. Many studies have investigated cross-sex friendships without taking into account the sexual identity of the participants (Buhrke & Fuqua, 1987; Fehr, 1996; Gaines, 1994; Monsour, 1992; O’Meara, 1989; Parker & de Vries, 1993; Reid & Fine, 1992; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988; Swain, 1992, Werking, 1997) and therefore draw conclusions about cross-sex friendships and negotiation of sexual boundaries (O’Meara, 1989; Reid and Fine, 1992; Swain, 1992). -

Lavender-Notes-April-2017.Pdf

Lavender Notes Improving the lives of LGBT older adults through community building, education, and advocacy. Celebrating 22+ years of service and positive change April 2017 Volume 24, Issue 4 Stories of Our Lives Donald Silva and William Baillie Don and Bill met each other 50+ years ago and have been together since November of 1966. They bought their current house in East Oakland back in 1972. Not what many people would consider your "typical" couple, this long-term pair - finally married in 2008 before Prop. 8 was passed and subsequently thrown out by the Supreme Court - have spent many happy hours with Don dressed as a stunning woman and Bill his handsome male escort. Their lives started out in much more traditional ways, however. Don was born at Providence Hospital in Oakland on May 2nd, 1935, the youngest of three sons, to a working-class mechanic and his homemaker wife. Even as an infant, Don was frequently mistaken for a girl. "My Dad came from a very large family of 13 kids," Don explains, "so I was surrounded by family throughout my childhood. My grandfather had a ranch in DeCoto - which is now Union City - with a creek running through it. My brothers, cousins and I spent many happy days there working in the huge vegetable fields and playing at 'bare-ass beach'!" A member of the first class to graduate from San Lorenzo High School in 1953, Don half-heartedly dated a few girls, but knew at an early age that he was really more into boys. "I was mostly trying to cover my ass in high school, so people wouldn't know I was gay," Don recalls. -

Gay Men's Experiences of Alaskan Society in Their Coupled Relationships Markie Louise Christianson Blumer Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 Gay men's experiences of Alaskan society in their coupled relationships Markie Louise Christianson Blumer Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Blumer, Markie Louise Christianson, "Gay men's experiences of Alaskan society in their coupled relationships" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gay men's experiences of Alaskan society in their coupled relationships by Markie Louise Christianson Blumer A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Human Development and Family Studies (Marriage and Family Therapy) Program of Study Committee: Megan J. Murphy, Major Professor Warren J. Blumenfeld Sedahlia Jasper Crase Carolyn E. Cutrona Ronald Werner-Wilson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Markie Louise Christianson Blumer, 2008. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3307096 UMI Microform 3307096 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Fag Hags' Their Badge of H

From beards to best friends, it's time to give 'fag hags' their badge of h... https://theconversation.com/from-beards-to-best-friends-its-time-to-giv... Academic rigour, journalistic flair From beards to best friends, it’s time to give ‘fag hags’ their badge of honour October 4, 2017 5.45am AEDT Eric McCormack and Debra Messing as Will and Grace. NBC/IMDB The fag hag. Never were two more scornful words so spectacularly smashed together. Stereotypes Author around the fag hag, fruitfly, fish, handbag – whatever you’d care to call her – abound. Search the Internet and you’d believe she’s a sad, overweight, trashy woman with too many cats unable to snag her own boyfriend or husband. Derision comes from queer quarters almost as often as Phoebe Hart from straight bystanders. Lecturer, Film Screen & Animation, Queensland University of Technology However, a closer examination of the history of the everyday fag hag and her references in pop culture reveals a more subversive and courageous figure. Fag hags have gone from “beards” who hide their gay friends’ sexuality to fashionable best friends epitomised by Grace in the TV series Will and Grace, which has just been revived. Further reading: Faggots, punks, and prostitutes: the evolving language of gay men It could be time to recast the moniker of “fag hag” as a badge of honour rather than a term of abuse. For the gay man, she has been protector, carer, cheerleader. For her, it is often an act of support. For the straight woman, he is a male friend that doesn’t expect more, a confidante, and just possibly the reason to become more involved in lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) activism. -

Femalemasculi Ni Ty

FEMALE MASCULINITY © 1998 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper oo Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Frontispiece: Sadie Lee, Raging Bull (1994) Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. FOR GAYAT RI CONTENTS Illustrations ix Preface xi 1 An Introduction to Female Masculinity: Masculinity without Men r 2 Perverse Presentism: The Androgyne, the Tribade, the Female Husband, and Other Pre-Twentieth-Century Genders 45 3 "A Writer of Misfits": John Radclyffe Hall and the Discourse of Inversion 7 5 4 Lesbian Masculinity: Even Stone Butches Get the Blues nr 5 Transgender Butch: Butch/FTM Border Wars and the Masculine Continuum 141 6 Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film 175 7 Drag Kings: Masculinity and Performance 231 viii · Contents 8 Raging Bull (Dyke): New Masculinities 267 Notes 279 Bibliography 307 Filmography 319 Index 323 IL LUSTRATIONS 1 Julie Harris as Frankie Addams and Ethel Waters as Bernice in The Member of the Wedding (1953) 7 2 Queen Latifahas Cleo in Set It Off(19 97) 30 3 Drag king Mo B. Dick 31 4 Peggy Shaw's publicity poster (1995) 31 5 "Ingin," fromthe series "Being and Having," by Catherine Opie (1991) 32 6 "Whitey," fromthe series "Being and Having," by Catherine Opie (1991) 33 7 "Mike and Sky," by Catherine Opie (1993) 34 8 "Jack's Back II," by Del Grace (1994) 36 9 "Jackie II," by Del Grace (1994) 37 10 "Dyke," by Catherine Opie (1992) 39 11 "Self- -

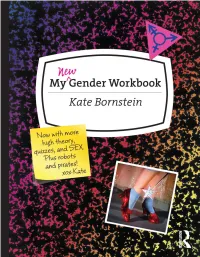

MY New Gender Workbook This Page Intentionally Left Blank N E W My Gender Workbook

my name is ________________________ and this is MY new gender workbook This page intentionally left blank N e w My Gender Workbook A Step-by-Step Guide to Achieving World Peace Through Gender Anarchy and Sex Positivity Kate Bornstein Routledge Taylor & Francis Group NEW YORK AND LONDON Second edition published 2013 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 Taylor & Francis The right of Kate Bornstein to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. First edition published by Routledge 1998 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bornstein, Kate, 1948– My new gender workbook: a step-by-step guide to achieving world peace through gender anarchy and sex positivity/ Kate Bornstein.—2nd ed. p. cm. Rev. ed. of: My gender workbook. 1998. 1. Gender identity. 2. Sex (Psychology) I. Bornstein, Kate, 1948– My gender workbook. II. -

The (Class) Struggle Is Real(Ly Queer): a Bilateral Intervention Into Working-Class Studies and Queer Theory

THE (CLASS) STRUGGLE IS REAL(LY QUEER): A BILATERAL INTERVENTION INTO WORKING-CLASS STUDIES AND QUEER THEORY by Katherine Anne Kidd B.A. University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, 2006 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEITRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Katherine Anne Kidd It was defended on August 8, 2016 and approved by William Scott, PhD, Associate Professor Mark Lynn Anderson, PhD, Associate Professor Brent Malin, PhD, Associate Professor Dissertation Co-Chair: Nancy Glazener, PhD, Associate Professor Dissertation Co-Chair: Nicholas Coles, PhD, Associate Professor ii Copyright © by Katherine Anne Kidd 2016 iii THE (CLASS) STRUGGLE IS REAL(LY QUEER): A BILATERAL INTERVENTION INTO WORKING-CLASS STUDIES AND QUEER THEORY Katherine Anne Kidd, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Class issues have become more present in media and literary studies, as the gap between the upper and lower classes has widened. Meanwhile, scholars in the growing field of working- class studies attempt to define what working-class literature is by formulating criteria for what kinds of people count as working-class, based on moral values supposedly held by working-class people. Usually, working-class people are envisioned as white, heteronormative, and dignified legitimate workers. Working-class studies seldom engages with queer theory or conventional forms of identity politics. Conversely, queer theorists often reference class, but abandon it in favor of other topics. -

Worlds of Wonder

The Queerness of Childhood Administrative Support: Worlds of Wonder Linda Saharczewski justin adkins May 3-5, 2013 Amy Merselis Williams College Interdisciplinary Workshop Panels all 3 days in Griffin 3 This workshop is sponsored by: Oakley Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences * Dively Committee for Human Sexuality and Diversity * Office of the Dean of the Faculty * History Department * English Department * Davis Center * Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies * German and Russian Department * Theater Department * Schumann Fund * Lecture Committee * Anthropology and Sociology Department * Psychology Department * American Studies * Queer Student Union More conference info: sites.williams.edu/worlds-of-wonder THE OAKLEY CENTER FOR THE HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES THE DIVELY COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN SEXUALITY AND DIVERSITY Day One: Friday, May 3 Day Two: Saturday, May 4 Paresky Auditorium Griffin 3 7:00pm 9.30am OPENING REMARKS KEYNOTE ADDRESS: The Anarchy of Childhood Anna Fishzon (Williams College) Jack Halberstam Anastasia Kayiatos (University of Southern California) J a c k H a l b e r s t a m , 10.00am – 11.30am PANEL 1 Professor of American QUEER PASTS: NARRATIVES OF DEVELOPMENT AND NORMATIVITY Studies and Ethnicity, G e n d e r S t u d i e s a n d Chair: Leyla Rouhi (Williams College) Comparative Literature at Karen Sánchez-Eppler (Amherst College) Queering America’s Progress Narrative: the University of Southern The California Ruins of Leland Stanford Jr. California. Halberstam is the author of five books, Allison Miller (Rutgers University) Progressive Penology Meets Youthful including: Skin Shows: Queerness in the Interwar United States Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters Michael O’Loughlin (Adelphi University) On Spectrality and History: Is a (Duke UP, 1995), Female Normative Interpellated Childhood Inevitable? Masculinity (Duke UP, LUNCH BREAK 1998), In A Queer Time and Place (NYU Press, 2005), The Queer Art of Failure (Duke UP, 2011) and Gaga Feminism: 1.00pm – 2.30pm PANEL 2 Sex, Gender, and the End of Normal (Beacon Press, 2012). -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

The Desired Unsung: Black Middle-Class Men and Intimate Relationships

The Desired Unsung: Black Middle-Class Men and Intimate Relationships by Joy L. Hightower A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Raka Ray, Chair Professor Victoria Bonnell Professor Sandra Smith Professor Ula Taylor Summer 2017 © Copyright by Joy L. Hightower, 2017. All rights reserved. Abstract The Desired Unsung: Black Middle-Class Men and Intimate Relationships by Joy L. Hightower Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Raka Ray, Chair Popular discourses about the crises of Black family, marriage, and economic stability are refracted through the failure of low-income Black men. But, the academic discussion is also tinged by the “taint of the ghetto,” in which sociologists have tended to analyze the diverse experiences of Black relationships through a reductionist frame based on poverty and family disorganization. Black middle-class (BMC) men also carry the weight of these class-specific narratives (e.g., the absentee father, philanderer, drug dealer, or gang member)—not just because there is a dearth of knowledge about BMC heterosexual relationships but because everyone else—from single mothers, never married women, social commentators, and pundits—are speaking for Black men, except themselves. Based on in-depth interviews, this dissertation seeks to enrich the debate surrounding Black relationships by including the -

Trans Studies

TRANS STUDIES TRANS STUDIES The Challenge to Hetero/Homo Normativities Edited by Yolanda Martínez- San Miguel and Sarah Tobias Rutgers University Press New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Trans studies : the challenge to hetero/homo normativities / edited by Yolanda Martínez- San Miguel and Sarah Tobias. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978– 0– 8135– 7641– 1 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978– 0– 8135– 7640– 4 (pbk. : alk. paper)— ISBN 978– 0– 8135– 7642– 8 (e- book (epub))— ISBN 978– 0– 8135– 7643– 5 (e- book (web pdf)) 1. Transgender people. 2. Transgenderism— Study and teaching. 3. Gender iden- tity. I. Martínez- San Miguel, Yolanda. II. Tobias, Sarah, 1963– HQ77.9.T71534 2016 306.76'8— dc23 2015021888 A British Cataloging- in- Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. This collection copyright © 2016 by Rutgers, The State University Individual chapters copyright © 2016 in the names of their authors All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is “fair use” as defined by U.S. copyright law. Visit our website: http:// rutgerspress .rutgers .edu Manufactured in the United States of America This book is dedicated to the memory of Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, and to all those trans activists who work to imagine and create a more just world.