Traditional Folk Diet: the Culinary Example

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Articles All Faculty Scholarship Spring 1-1-2003 Wendy A. Woloson. Refined aT stes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2003). Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America. Winterthur Portfolio, 38(1), 72–76. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/70 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72 Winterthur Portfolio 38:1 upon American material life, the articles pri- ture, anthropologists, and sociologists as well as marily address objects and individuals within the food historians. It also serves as a vivid account Delaware River valley. Philadelphia, New Jersey, of the emergence of consumer culture in gen- and Delaware are treated extensively. Outlying eral, focusing on the democratization of once- Quaker communities, such as those in New En- expensive sweets due to new technologies and in- gland, North Carolina, and New York state, are es- dustrial production and their shift from symbols sentially absent from the study. Similarly, the vol- of power and status to indulgent ephemera best ume focuses overwhelmingly upon the material life left to women and children. -

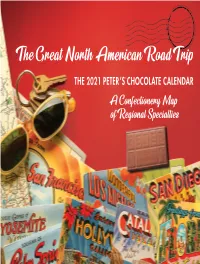

A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties

The Great North American Road Trip THE 2021 PETER’S® CHOCOLATE CALENDAR A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties One of the great pleasures of domestic travel in North America is to see, hear and taste the regional differences that characterize us. The places where we live help shape the way we think, the way we talk and even the way we eat. So, while chocolate has always been one of the world’s great passions, the ways in which we indulge that passion vary widely from region to region. In this, our 2021 Peter’s Chocolate Calendar, we’re celebrating the great love affair between North Americans and chocolate in all its different shapes, sizes, and flavors. We hope you’ll join us on this journey and feel inspired to recreate some of the specialties we’ve collected along the way. Whether it’s catfish or country-fried steak, boiled crawfish or peach cobbler, Alabama cuisine is simply divine. Classic southern recipes are as highly prized as family heirlooms and passed down through the generations in the Cotton State. This is doubtless how the confection known as Southern Divinity built its longstanding legacy in this region. The balanced combination of salty and sweet is both heavenly and distinctly Southern. Southern Divinity Southern Divinity Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat Ingredients: December February 1 001 2 002 2 Egg Whites S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 17 oz Sugar 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 56 6 oz Light Corn Syrup 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 4 oz Water 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 1 tbsp Vanilla Extract 27 28 29 30 31 28 New Year’s Day 6 oz Coarsely Chopped Pecans, roasted & salted Peter’s® Marbella™ Bittersweet Chocolate, 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 for drizzling Directions: Beat egg whites in a stand mixer until stiff National Chocolate peaks form. -

July 26, 2019

d's Dairy orl In W du e st h r t y g W n i e e v Since 1876 k r e l y S NEW 2-PIECE DESIGN CHEESE REPORTER Precise shreds with Urschel Vol. 144, No. 6 • Friday, July 26, 2019 • Madison, Wisconsin USDA Details Product Purchases, US Milk Production Rose 0.1% In June; Other Aspects Of Farmer Trade Aid Second-Quarter USDA’s Ag Marketing vice (FNS) to food banks, schools, a vendor for distribution to indus- Output Down 0.1% Service To Buy $68 Million and other outlets serving low- try groups and interested parties. Washington—US milk produc- income individuals. Also, AMS will continue to tion in the 24 reporting states In Dairy Products, Starting AMS is planning to purchase an host a series of webinars describ- during June totaled 17.35 billion After Oct. 1, 2019 estimated $68 million in milk and ing the steps required to become pounds, up 0.1 percent from June Washington—US Secretary of other dairy products through the a vendor. 2018, USDA’s National Agricul- Agriculture Sonny Perdue on FPDP. Stakeholders will have the tural Statistics Service (NASS) Thursday announced details of the AMS will buy affected products opportunity to submit questions to reported Monday. $16 billion trade aid package aimed in four phases, starting after Oct. be answered during the webinar. The May milk production esti- at supporting US dairy and other 1, 2019, with deliveries beginning The products discussed in the mate was revised upward by 18 agricultural producers in response in January 2020. -

Delivery Menu

٨ ﻃﻤﺎﻃﻢ ﻣﺠﻔﻔﺔ Cevizli Domates Kurusu 1.900 KD 8 ﻃﻤﺎﻃﻢ ﻣﺠﻔﻔﺔ ﺗﻘﺪم ﻣﻊ اﻟﺠﻮز COLD APPETIZERS Sun-dried tomatoes served with وزﻳﺖ اﻟﺰﻳﺘﻮن ودﺑﺲ اﻟﺮﻣﺎن olive oil, walnuts and Soğuk Mezeler pomegranate sauce 9 Abagannuş 1.600 KD ٩ اﺑﺎ ﻏﺎﻧﻮس Cacik �1.400 KD SALADS ﺑﺎذﻧﺠﺎن ﻣﺸﻮي وﻣﺘﺒﻞ ﺑﺰﻳﺖ اﻟﺰﻳﺘﻮن Grilled eggplant mixed with virgin olive ١ ﺧﻴﺎر ﺑﺎﻟﻠﺒﻦ 1 واﻟﺰﺑﺎدي اﻟﻤﻨﺰﻟﻲ واﻟﺜﻮم اﻟﻄﺎزج oil, homemade yoghurt and fresh garlic ﺧﻴﺎر ﻣﻘﻄﻊ وﺛﻮم ﻣﻔﺮوم وﻧﻌﻨﺎع Diced cucumber, crushed garlic Salatalar ﻣﻤﺰوج ﺑﺎﻟﻠﺒﻦ اﻟﻄﺎزج and mint in fresh yoghurt ١ ﺳﻠﻄﺔ اﻟﻐﺎﻓﻮردا Gavurdağı Salata� 2.000 KD 1 ﻣﻜﻌﺒﺎت ﻣﻦ اﻟﻄﻤﺎﻃﻢ وﻗﻄﻊ Cubed tomatoes with finely ١٠ ﻣﺘﺒﻞ اﻟﺒﺎذﻧﺠﺎن Patlıcan Salatası 1.400 KD 10 ٢ ﺣﻤﺺ Hummus� 1.600 KD 2 اﻟﺒﺼﻞ chopped onions and Turkish ﺑﺎذﻧﺠﺎن ﻣﻬﺮوس وﻣﺘﺒﻞ ﺑﺰﻳﺖ اﻟﺰﻳﺘﻮن Barbecued eggplant, puréed and ﺣﻤﺺ ﻣﻌﺪ ﻋﻠﻰ اﻟﻄﺮﻳﻘﺔ اﻟﻤﻨﺰﻟﻴﺔ Homemade hummus drizzled with اﻟﻤﺘﺒﻠﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﺒﻬﺎرات اﻟﺘﺮﻛﻴﺔ ﺗﻘﺪم ﻣﻊ herbs, served with walnuts and اﻟﺒﻜﺮ lightly mixed with virgin olive oil ﻣﻀﺎف إﻟﻴﻪ زﻳﺖ اﻟﺰﻳﺘﻮن اﻟﺤﺎر chilli oil FROM THE WOOD OVEN دﺑﺲ اﻟﺮﻣﺎن واﻟﺠﻮز pomegranate sauce 11 Taş Fırından ١١ ورق ﻋﻨﺐ Dolma 1.900 KD ٣ أرﺿﻲ ﺷﻮﻛﻲ Enginar �1.600 KD 3 ٢ ﺳﻠﻄﺔ اﻟﺘﻮروس Toros Salata �1.900 KD 2 ورق ﻋﻨﺐ ﺑﺎﻟﺰﻳﺖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﺨﻀﺮاوات وا رز Vine leaves stuffed with rice and ﻗﻄﻊ ﻣﺨﺘﺎرة ﻣﻦ ﻗﻠﺐ اﻟﺨﺮﺷﻮف Heart of artichokes served with ١ ﻓﻄﻴﺮة اﻟﻠﺤﻢ vegetables Signature salad with finely chopped Lahmacun� 2.000 KD 1 ﺳﻠﻄﺔ اﻟﺠﺮﺟﻴﺮ واﻟﻨﻌﻨﺎع واﻟﺒﺼﻞ ﺗﻘﺪم ﻣﻊ اﻟﺠﺰر واﻟﺒﻄﺎﻃﺎ وﺣﺒﺎت carrots, potato and peas ﻓﻄﻴﺮة ﻣﺤﻤﺼﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﻠﺤﻢ اﻟﻤﻔﺮوم Thin Turkish pizza with seasoned ا ﺧﻀﺮ واﻟﻄﻤﺎﻃﻢ واﻟﺒﻘﺪوﻧﺲ tomatoes, rocket, -

Meat and Muscle Biology™ Introduction

Published June 7, 2018 Meat and Muscle Biology™ Meat Science Lexicon* Dennis L. Seman1, Dustin D. Boler2, C. Chad Carr3, Michael E. Dikeman4, Casey M. Owens5, Jimmy T. Keeton6, T. Dean Pringle7, Jeffrey J. Sindelar1, Dale R. Woerner8, Amilton S. de Mello9 and Thomas H. Powell10 1University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA 2University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 4Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA 5University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA 6Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 7University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA 8Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA 9University of Nevada, Reno, NV, 89557, USA 10American Meat Science Association, Champaign, IL 61820, USA *Inquiries should be sent to: [email protected] Abstract: The American Meat Science Association (AMSA) became aware of the need to develop a Meat Science Lexi- con for the standardization of various terms used in meat sciences that have been adopted by researchers in allied fields, culinary arts, journalists, health professionals, nutritionists, regulatory authorities, and consumers. Two primary catego- ries of terms were considered. The first regarding definitions of meat including related terms, e.g., “red” and “white” meat. The second regarding terms describing the processing of meat. In general, meat is defined as skeletal muscle and associated tissues derived from mammals as well as avian and aquatic species. The associated terms, especially “red” and “white” meat have been a continual source of confusion to classify meats for dietary recommendations, communicate nutrition policy, and provide medical advice, but were originally not intended for those purposes. -

Wholesome Harvest Box Info

Wholesome Harvest Box Info What’s in my box? This list is tentative and subject to change. Please visit our website’s current news box for any changes. Giant Kohlrabi Sweetheart Cabbage Cipollini Onion Zucchini Cucumber Cherry Tomatoes Arugula Varieties of tomatoes Scallions Roasted Sweetheart Cabbage Beefsteak Tomato The Vegetables Giant Kohlrabi The giant kohlrabi variety will last several months in cool dry storage. Sweetheart Cabbage To prepare, remove any damaged outer leaves and cut the cabbage in half and then into quarters, cut off the hard core from each quarter at an angle. Slice and wash thoroughly. Roast with a drizzle (or more) of olive oil and season with salt and pepper. Cipollini Onions Keep these onions at room temperature to cure, or store in the fridge for more immediate use. The Cipollini’s unique shape makes it a great addition to mixed roasted vegetables (such as carrots, fennel, beets, eggplant, and zucchini) Cucumber A quick jar of pickled cucumber slices is as easy as slicing the cucumbers into thin discs, stuffing them into a glass jar, adding some sliced onions, and topping with water, seasoned rice vinegar, some honey, and salt. Shake the jar to mix in the ingredients and serve any time. Cherry Tomatoes Feel free to leave you tomatoes at room temp or in the fridge. Enjoy whole or cut as a sweet acidic addition to avocado toast, pasta, tacos, or an omelet! Arugula Your arugula has already been rinsed before it came home to you, but be sure to give it a final wash and dry/spin before using. -

Halušky with Sauerkraut

Halušky with Sauerkraut 4 servings Active Time: 35 min. Total Time: 35 min. Level of Advancement: 1/5 Halušky are most likely the easiest pasta meal made from scratch. It is superfast and at the same time, super tasty. Halušky are a traditional Slovak Shepherd’s meal. Ingredients: Halušky batter: 2 LB of potatoes 1 large egg ½ TSP of salt 2 ½ cups of all-purpose flour Sauerkraut: 2 TBSP of frying oil - adjust if needed 1 large onion - peeled and finely chopped ½ LB of bacon - chopped into small pieces * 1 LB of Sauerkraut (drained, amount before draining) ½ Stick (2 OZ) of butter ½ TSP of salt ½ TSP of ground pepper * Skip for a vegetarian option Tools: Chef's Knife & Cutting Board Measuring Spoons & Measuring Cups Peeler Box Grater or Kitchen Mixer with Grater Attachment or Food Processor Immersion Blender or Food Processor or Blender 2 Large Mixing Bowls (about 8 QT or more) Silicone Spatula Large Sauce Pan or Medium Pot (about 6 QT) Large Fry Pan or Large Stir Fry Pan - Wok or Large Sauté Pan (12" or more) Halusky/Spaetzle Press or Colander (with Holes about ¼”) Strainer www.cookingwithfamily.com Cooking with Family © 2021 1 Directions: 1. Potato preparation: 1.1. Briefly rinse the potatoes under cold water and then peel. 1.2. Shred the potatoes into a large mixing bowl. Use the fine-sized holes for shredding. 2. Halušky batter: 2.1. Add: 1 large egg ½ TSP of salt Thoroughly stir together with a spatula until nicely combined. 2.2. Process until smooth with an immersion blender. 2.3. -

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

The Mineral Waters of Europe

ffti '.>\V‘ :: T -T'Tnt r TICEB9S5S & ;v~. >Vvv\\\\\vSVW<A\\vvVvi% V\\\WvVA ^.« .\v>V>»wv> ft ‘ai^trq I : ; ; THE MINERAL WATERS OF EUROPE: INCLUDING T DESCRIPTION OF ARTIFICIAL MINERAL WATERS. BY TICHBORNE, LL.D, F.C.S., M.R.I.A., Fellow of the Institute of Chemistry of Great Britain and Ireland ; Professor of Chemistry at the Carmichael College of Medicine, Dublin; Late Examiner in Chemistry in the University of Dublin; Professor of Chemistry, Apothecaries' Hall of Ireland ; President of the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland Honorany and Corresponding Member of the Philadelphia and Chicago Colleges of Pharmacy ; Member of the Royal Geological Society of Ireland Analyst to the County of Longford ; £c., £c. AND PROSSER JAMES, M.D., M.R.C.P., Lecturer on Materia Medica and Therapeutics at the London Hospital; Physician to the Hospital for Diseases of the Throat and Chest ; Late Physician to the North London Consumption Hospital; Ac., tCc., &c. LONDON BAILLIERE, TINDALL & COX. 1883. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/b21939032 PREFACE. Most of the objects had in view in writing the present work have been incidentally mentioned in the Introductory Chapter. It may, however, be desiderable to enumerate concisely the chief points which have actuated the authors in penning the “ Mineral Waters of Europe.” The book is intended as a reliable work of reference in connection with the chief mineral waters, and also to give the character and locality of such other waters as are in use. In many of the books published upon the subject the analyses given do not represent the present com- position of the waters. -

Quality Hungarian Style Sausages

www.bende.com No. 1R Quality Hungarian Style Sausages Always made with top quality natural ingredients and naturally smoked to make this a sausage our family is proud to produce. Sausage Excellence for Over 70 Years A Proud Heritage The Bende family has been in the food trade since 1935 when a young Miklos Sr. opened his first grocery store in Hungary. He ran several grocery stores in Budapest and Miskolc before immigrating with his wife and young son in 1956. Soon after arriving in the United States, the family returned to its meat cutting and grocery roots, opening the first Bende store in Chicago’s Burnside neighborhood. Sev- eral stores followed, as did a reputation for preparing out- standing smoked meats. While we have grown and adopted new technologies, we still use the original old world recipes carried from Hungary by our grandfather. Using only the most authentic ingredients allows us to remain true to our high family standards and proud Hungarian heritage. Left top, our Lincoln Avenue store, circa 1964. Left, second and third from top, the meat processing plant, distribution and retail shop in Vernon Hills, Illinois. Bottom, the retail shop in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. Near left, Miklos Bende Sr. and his wife Julia. Above, Miklos II and his wife Brigitte. Right, the Bende grocery store, Miskolc, Hungary, circa 1935. Below, the Bende third generation, Mark, Miklos III, Enikö and Erik. 2 Order at www.bende.com Order at www.bende.com 3 A. Long “Teli” Salami (In white casing, approx. 2LB) Vac. Packed #1111 B. Short “Teli” Salami Meat (In white casing, approx. -

Detailed Instructions of the Electric Pyrolytic Oven

GB IE MT DETAILED INSTRUCTIONS OF THE ELECTRIC PYROLYTIC OVEN www.gorenje.com We thank you for your trust in purchasing our appliance. This detailed instruction manual is supplied to allow you to learn about your new appliance as quickly as possible. Make sure you have received an undamaged appliance. Should you notice any transport damage, please notify your dealer or regional warehouse where your appliance was supplied from. The telephone number can be found on the invoice or on the delivery note. Instructions for installation and connection are supplied on a separate sheet. Instructions for use are also available at our website: www.gorenje.com / < http://www. gorenje.com /> Important information Tip, note CONTENTS WARNINGS 4 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS 6 Before connecting the appliance 7 THE ELECTRIC PYROLYTIC OVEN INTRODUCTION 10 Control unit 12 Information on the appliance - data plate (depending on the model) 13 BEFORE THE FIRST USE INITIAL PREPARATION OF THE 14 FIRST USE APPLIANCE 15 SELECTING THE MAIN MENUS FOR BAKING AND SETTINGS SETTINGS AND BAKING 16 A) Baking by selecting the type of food (automatic mode auto) 18 B) Baking by selecting the mode of operation (professional (pro) mode) 24 C) Storing your own programme (my mode) 25 START OF BAKING 25 END OF BAKING AND OVEN SHUT-OFF 26 SELECTING ADDITIONAL FEATURES 28 SELECTING GENERAL SETTINGS 30 DESCRIPTIONS OF SYSTEMS (COOKING MODES) AND COOKING TABLES 45 MAINTENANCE & CLEANING CLEANING AND MAINTENANCE 46 Conventional oven cleaning 47 Automatic oven cleaning – pyrolysis 49 Aqua clean cleaning program 50 Removing and cleaning wire and telescopic extendible guides 51 Removing and inserting the oven door 53 Removing and inserting the oven door glass pane 54 Replacing the bulb PROBLEM 55 TROUBLESHOOTING TABLE SOLVING 56 DISPOSAL 697193 3 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY READ THE INSTRUCTIONS AND SAVE THEM FOR FUTURE REFERENCE. -

Grand Fiesta Americana Coral Beach Cancun Serves up Culinary Excellence with Three New Talented Chefs

GRAND FIESTA AMERICANA CORAL BEACH CANCUN SERVES UP CULINARY EXCELLENCE WITH THREE NEW TALENTED CHEFS CANCUN, MEXICO (AUGUST X, 2018) – Grand Fiesta Americana Coral Beach Cancun, located on Cancun’s most secluded stretch of white sand beach, is flexing its culinary muscles with the arrival of three ultra-talented new chefs to the resorts already impressive dining program. Chef Mariana Alegría Gárate, Chef Gerardo Corona, and Chef Juan Antonio Palacios, bring their own creative flair and unique skill set to their respective award-winning restaurants. As the first female to lead a kitchen at the resort, Chef de Cuisine Mariana Alegría Gárate oversees Le Basilic Restaurant, one of just seven restaurants in Mexico to receive AAA Five Diamonds. With an impressive background and education, Gárate has worked hard to make it to the top spot of this award-winning restaurant. She won the coveted Loredo Medal while earning her Master’s Degree in gastronomy with a focus on Spanish, Italian and Mexican cuisine, then followed up with a specialty in French cuisine at Monte Carlo’s Lycée Technique et Hôtelier de Monaco. Further inspired, she received her Diploma from the Mexican School of Sommeliers, allowing her to share her deep passion for wine with her guests. As for her practical experience, she was most recently Sous Chef at Mexico City’s celebrated Balcón del Zócalo in the Zócalo Central Hotel, did a stint with the highly unique concept of Dinner In The Sky, and worked the line for the legendary Alain Ducasse at his restaurant miX On The Beach at the W Vieques, Puerto Rico.