Our History: 20 Years of Watching Your Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Wilderness Within the Context of Larger Systems; 1999 May 23–27; Missoula, MT

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Science in a Forest Service Time of Change Conference Rocky Mountain Research Station Proceedings Volume 2: Wilderness Within RMRS-P-15-VOL-2 the Context of Larger Systems September 2000 Missoula, Montana May 23–27, 1999 Abstract McCool, Stephen F.; Cole, David N.; Borrie, William T.; O’Loughlin, Jennifer, comps. 2000. Wilderness science in a time of change conference—Volume 2: Wilderness within the context of larger systems; 1999 May 23–27; Missoula, MT. Proceedings RMRS-P-15-VOL-2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Thirty-eight papers related to the theme of wilderness in the context of larger systems are included. Three overview papers synthesize existing knowledge and research about wilderness economics, relationships between wilderness and surrounding social communities, and relation- ships between wilderness and surrounding ecological communities and processes. Other papers deal with wilderness meanings and debates; wilderness within larger ecosystems; and social, economic, and policy issues. Keywords: boundaries, ecological disturbance, ecosystem management, regional analysis, wilderness economics, wilderness perception RMRS-P-15-VOL-1. Wilderness science in a time of change conference—Volume 1: Changing perspectives and future directions. RMRS-P-15-VOL-2. Wilderness science in a time of change conference—Volume 2: Wilderness within the context of larger systems. RMRS-P-15-VOL-3. Wilderness science in a time of change conference—Volume 3: Wilderness as a place for scientific inquiry. RMRS-P-15-VOL-4. Wilderness science in a time of change conference—Volume 4: Wilderness visitors, experiences, and visitor management. -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

Hiking the Appalachian and Benton Mackaye Trails

10 MILES N # Chattanooga 70 miles Outdoor Adventure: NORTH CAROLINA NORTH 8 Nantahala 68 GEORGIA Gorge Hiking the Appalachian MAP AREA 74 40 miles Asheville co and Benton MacKaye Trails O ee 110 miles R e r Murphy i v 16 Ocoee 64 Whitewater Center Big Frog 64 Wilderness Benton MacKaye Trail 69 175 Copperhill TENNESSEE NORTH CAROLINA Appalachian Trail GEORGIA GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 75 1 Springer Mountain (Trail 15 Epworth spur T 76 o 60 Hiwassee Terminus for AT & BMT) 2 c 2 5 c 129 Cohutta o Wilderness S BR Scenic RRa 60 Young 2 Three Forks F R Harris 288 iv e 3 Long Creek Falls r Mineral 14 Bluff Woody Gap 2 4 Mercier Brasstown 5 Neels Gap, Walasi-Yi Orchards F Bald S 64 13 Lake Morganton Blairsville Center Blue 515 17 6 Tesnatee Gap, Richard Ridge old Blue 76 Russell Scenic Hwy. Ridge 129 A s 7 Unicoi Gap k a 60 R oa 180 8 Toccoa River & Swinging Benton TrailMacKaye d 7 12 10 Bridge 9 Vogel 9 Wilscot Gap, Hwy 60 11 Cooper Creek State Park Scenic Area Shallowford Bridge Rich Mtn. 75 10 Wilderness 11 Stanley Creek Rd. 515 8 180 5 Toccoa 6 12 Fall Branch Falls 52 River 348 BMT Trail Section Distances (miles) 13 Dyer Gap (6.0) Springer Mountain - Three Forks 19 Helen (1.1) Three Forks - Long Creek Falls 3 60 14 Watson Gap (8.8) Three Forks - Swinging Bridge FS 15 Jacks River Trail Ellijay (14.5) Swinging Bridge - Wilscot Gap 58 Suches (7.5) Wilscot Gap - Shallowford Bridge F S Three (Dally Gap) (33.0) Shallowford Bridge - Dyer Gap 4 Forks 4 75 (24.1) Dyer Gap - US 64 2 2 Appalachian Trail 129 alt 16 Thunder Rock Atlanta 19 Campground -

Hogpen Gap to Rocky Mountain (Unicoi Gap) Trail

AT – Hogpen Gap to Rocky Mountain (Unicoi Gap) Trail Departure Destination: Hogpen Gap, Water Availability: From the city of Helen, travel North on GA-75 1.4 miles north of 4.2mi – spring the Chattahoochee River bridge. Turn left on Alt 75 S at the large 4.6mi – stream flea market. Continue south 2.3 miles and then turn right on the 9.2mi – spring Richard B. Russell Scenic Highway a.k.a. GA-348. Continue 11.3mi - spring winding northward on GA-348 for approximately 7 miles where you will find the large parking area for Hogpen Gap. Car Drop Location: Unicoi Gap 9 Miles north of Helen on GA-75. Large parking area. Rating: Moderate USGS Quadrangles: Cowrock Distance: 15.6 Miles Emergency Numbers: 911 Local Police Union County Sheriff 706.439.6066 1:00-4:30 open Local Police White County Sheriff 706.865.0911 Nearest Hospital Union General Hospital 706.745.2111 Poison Control National Center 800.222.1222 Land Management Office: Ranger Station: Chattooga River District Dave Jensen - District Ranger Note: Some of the roads taken to reach the trailhead overlap the 809 Highway 441 South popular bicycle route known as Six Gap. Please be mindful of Clayton, GA 30525 cyclists and share the road politely. They have as much right to Phone: 706.782.3320 the road as the rest of us. s Fax: 706.782.2079 Office hours: Monday - Friday 8:00-12:00 open Description AT Section 4 Description: Section 4 of the Appalachian Trail is, by a considerable margin, the shortest and easiest section in the Peach State. -

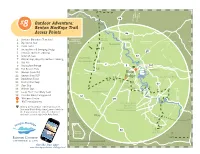

Benton Mackaye Trail Access Points 64

CAROLINA NORTH TENNESSEE ee o c R O i v er 68 # Outdoor Adventure: 18 8 Benton MacKaye Trail Access Points 64 Big Frog Copperhill 1 Springer Mountain (Terminus) TENNESSEE Mountain Big Stamp Gap 2 GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 3 Three Forks 17 4 Toccoa River & Swinging Bridge T spur o c 60 5 Hwy 60, southern crossing 2 c 2 o a S 6 Skeenah Gap F R 60 iv Cohutta e 7 Wilscot Gap, Hwy 60, northern crossing r Wilderness 8 Dial Rd. 16 2 5 515 Shallowford Bridge 9 old 76 Fall Branch Falls Lake 10 FS 64 15 Morganton Blue 11 Weaver Creek Rd. FANNIN COUNTY Blue Ridge 12 Georgia Hwy 515 GILMER COUNTY 13 Ridge A Skeenah Gap Road Boardtown Road s 13 14 k 12 a 14 Bushy Head Gap 11 R Rich oa 60 15 Dyer Gap Mtn d Wilderness 8 FANNIN COUNTY FANNIN 16 Watson Gap 10 6 COUNTY UNION Boardtown Road 7 17 Jacks River Trail (Dally Gap) 9 18 Thunder Rock Campground 52 Welcome Center 515 5 BMT Headquarters 4 Stanley Creek Road To a cco River Old Dial Road Getting to Aska Road: From Highway 515, S u Newport Road turn onto Windy Ridge Road, go one block to r r Doublehead Gap Road the 3 way stop intersection, then turn left o FS u and make a quick right onto Aska Road. n 58 d Ellijay e 3 F Three d S B 4 Forks y 2 F o re st 2 s 52 1 GEORGIA Springer Mountain MAP AREA AT N BMT 10 MILES Get the free App! ©2016 TreasureMaps®.com All rights reserved www.blueridgemountains.com/App.html Fort Loudoun Lake Rockford Lenoir City Mentor E HUNT RD Cherokee National Forest SU Pigeon Forge G D T AR R Watts Bar Lake en L Fort Loudoun Lake Alcoa P Watts Bar Lake n I Y e M 1 ig s B R -

Page 1480 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1113 (Pub

§ 1113 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1480 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 13, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation § 1113. Authorization of appropriations System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- There are hereby authorized to be appro- priations be available for additional personnel priated to the Department of the Interior with- stated as being required solely for the purpose of out fiscal year limitation such sums as may be managing or administering areas solely because necessary for the purposes of this chapter and they are included within the National Wilder- the agreement with the Government of Canada ness Preservation System. signed January 22, 1964, article 11 of which pro- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined vides that the Governments of the United States A wilderness, in contrast with those areas and Canada shall share equally the costs of de- where man and his own works dominate the veloping and the annual cost of operating and landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where maintaining the Roosevelt Campobello Inter- the earth and its community of life are un- national Park. trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- (Pub. L. 88–363, § 14, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this chapter an CHAPTER 23—NATIONAL WILDERNESS area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its PRESERVATION SYSTEM primeval character and influence, without per- manent improvements or human habitation, Sec. which is protected and managed so as to pre- 1131. -

Third Infantry Division Highway Corridor Study

THIRD INFANTRY DIVISION HIGHWAY CORRIDOR STUDY Task 7 Study Alignments and Design Levels Draft Technical Memorandum 1. Executive Summary Section 1927 of the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA‐LU) (P.L. 109‐59) requires “a report that describes the steps and estimated funding necessary to designate and construct a route for the 3rd Infantry Division Highway,” extending from Savannah, Georgia to Knoxville, Tennessee, byy wa of Augusta, Georgia. The intent of this study is to develop planning level cost estimates for potential corridors connecting these urban areas. This information will be presented to Congress to fulfill the statutory language and present an overview of the steps necessary to construct such a corridor. The study is not intended to select an alternative for implementation; it will not necessarily lead to any further planning, design, right‐of‐way acquisition, or construction activities for any specific highway improvement. This technical memorandum recommends initial study corridors and design levels for the 3rd Infantry Division Highway corridors along with supporting justification and the rationale for the recommendations. Input from the Expert Working Group (EWG) was considered during the development of the Alignments and Design Levels. The EWG is a panel of area transportation officials and federal resource agencies that helps guide the project. The EWG serves as a sounding board to weigh technical options, examine issues from multiple perspectives and, by drawing upon its collective experience, help the team solve problems. Tasks 8‐9 in the study involve examining any corridors recommended for additional study in greater detail. -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Source: US House of Representatives Office of the Law This is the 1964 act that started it all Revision Counsel website at and created the first designated http://uscode.house.gov/download/ascii.shtml wilderness in the US and Nevada. This version, updated January 2, 2006, includes a list of all wilderness designated before that date. The list does not mention designations made by the December 2006 White Pine County bill. -CITE- 16 USC CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 01/02/2006 -EXPCITE- TITLE 16 - CONSERVATION CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -HEAD- CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -MISC1- Sec. 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of policy; wilderness areas; administration for public use and enjoyment, protection, preservation, and gathering and dissemination of information; provisions for designation as wilderness areas. (b) Management of area included in System; appropriations. (c) "Wilderness" defined. 1132. Extent of System. (a) Designation of wilderness areas; filing of maps and descriptions with Congressional committees; correction of errors; public records; availability of records in regional offices. (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classifications as primitive areas; Presidential recommendations to Congress; approval of Congress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado. (c) Review by Secretary of the Interior of roadless areas of national park system and national wildlife refuges and game ranges and suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; authority of Secretary of the Interior to maintain roadless areas in national park system unaffected. (d) Conditions precedent to administrative recommendations of suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; publication in Federal Register; public hearings; views of State, county, and Federal officials; submission of views to Congress. -

Georgia Appalachian Trail Club

GEORGIA APPALACHIAN TRAIL CLUB PLAN FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL IN GEORGIA DECEMBER 2006 1 Table Of Contents PART I. - Introduction A. Purpose B. Background PART II. - THE COOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM/PARTNERS A. The Georgia Appalachian Trail Club B. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy C. The National Park Service D. The U.S.D.A. Forest Service E. The State of Georgia F. Other AT Maintaining Clubs G. Environmental Groups H. Landowners PART III. - The PHYSICAL TRAIL A. Trail Standards B Trail Design/Location/Relocation C. Trail Construction and Maintenance D. Trail Shelters and Campsites E. Signs and Trail Markings F. Bridges and Stream Crossings G. Trail Heads and Parking H. Tools I. Water Sources J. Trail Monitoring Techniques K. Side Trails L. Safety M. Sanitation N. Memorials/Monuments PART IV. - PUBLIC USE, PUBLIC INFORMATION, AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE A. Emergency Planning and Coordination B. Special Events and Large Group Use C. Public Information and Education Programs D. Caretaker and Ridgerunner Programss E. Accessibility 2 PART V. - CONFLICTING USES AND COMPETING USES A. Vehicular Traffic B. Abandoned Personal Property C. Hunting D. Horses and Pack Animals E. Roads F. Special Uses G. Utilities and Communications Facilities H. Oil, Gas and Mineral Exploitation I. Military Operations J. Corridor Monitoring PART VI.- RESOURCE MANAGEMENT A. Open Areas and Vistas B. Timber Management C. Pest Management D. Threatened and Endangered Species E. Wildlife F. Vegetation Management and Reclamation G. Historical/Cultural/Natural Resources PART VII. - WILDERNESS A. Motorized Equipment B. Treadway Improvement C. Trail Standards D. Shelters E. Scenic Vistas F. Signs and Trail Markings G. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 207/Monday, October 26, 2020

67818 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 207 / Monday, October 26, 2020 / Proposed Rules ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION All submissions received must include 1. General Operation and Maintenance AGENCY the Docket ID No. for this rulemaking. 2. Biofouling Management Comments received may be posted 3. Oil Management 40 CFR Part 139 without change to https:// 4. Training and Education B. Discharges Incidental to the Normal [EPA–HQ–OW–2019–0482; FRL–10015–54– www.regulations.gov, including any Operation of a Vessel—Specific OW] personal information provided. For Standards detailed instructions on sending 1. Ballast Tanks RIN 2040–AF92 comments and additional information 2. Bilges on the rulemaking process, see the 3. Boilers Vessel Incidental Discharge National 4. Cathodic Protection Standards of Performance ‘‘General Information’’ heading of the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section of 5. Chain Lockers 6. Decks AGENCY: Environmental Protection this document. Out of an abundance of 7. Desalination and Purification Systems Agency (EPA). caution for members of the public and 8. Elevator Pits ACTION: Proposed rule. our staff, the EPA Docket Center and 9. Exhaust Gas Emission Control Systems Reading Room are closed to the public, 10. Fire Protection Equipment SUMMARY: The U.S. Environmental with limited exceptions, to reduce the 11. Gas Turbines Protection Agency (EPA) is publishing risk of transmitting COVID–19. Our 12. Graywater Systems for public comment a proposed rule Docket Center staff will continue to 13. Hulls and Associated Niche Areas under the Vessel Incidental Discharge provide remote customer service via 14. Inert Gas Systems Act that would establish national email, phone, and webform. We 15. Motor Gasoline and Compensating standards of performance for marine Systems encourage the public to submit 16. -

Disappearing Wildlands of Georgia Mountains and Rivers

Disappearing Wildlands of Georgia Mountains and Rivers Congressional Districts: 9 and 10 Dawson, Lumpkin, Gilmer, Murray, GEORGIA Members: Tom Graves and Paul Broun and Putnam Counties Location Northern mountains and central Piedmont Acquired to Date within an hour’s drive of Atlanta and Macon; 7 tracts on or adjoining Method Acres Cost ($) Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest: Purchase 3,485 $18,245,000 Chattahoochee (1), Oconee (1), Etowah Exchange 0 0 (1), Conasauga (3), and Coosawattee (1). Donation 599 $6,500,000 Partners 1,715 $10,945,000 Purpose Protect southern watersheds and other President’s List FY2011 non-renewable natural resources, while Method Acres Cost ($) reconnecting Americans to the great Purchase 390 $1,700,000 outdoors. President’s Budget FY12 Method Acres Cost ($) Purchase All owners are willing sellers, and a few Purchase 283 $2,000,000 Opportunities are open to a phased sale. Several tracts are under contract, subject to Federal Pending Future Request(s) funding. Discussions are underway with Method Acres Cost ($) Oconee and Conassauga owners. Purchase 1,214 $5,300,000 Partners The Nature Conservancy (Etowah), The Conservation Fund (Coosawattee), the Trust for Public Land (Chattahoochee). Cooperators include the Georgia Land Conservation Center, Trout Unlimited, The Wilderness Society, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Upper Etowah River Alliance, Georgia River Network, Southern Off Road Bicycle Association, Mountain Conservation Trust, and Appalachian Trail Conservancy. Project Georgia’s national forests are located near population centers that number in the millions, creating Description pressures for clean water and recreation that have far exceeded the forests’ ability to deliver. Especially worrisome are recent State water wars, pitting the needs of Atlanta homes and businesses against those of Alabama and Florida and putting fish-dependent economies of the Gulf Coast in jeopardy.