Brennan, Ruth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anke-Beate Stahl

Anke-Beate Stahl Norse in the Place-nam.es of Barra The Barra group lies off the west coast of Scotland and forms the southernmost extremity of the Outer Hebrides. The islands between Barra Head and the Sound of Barra, hereafter referred to as the Barra group, cover an area approximately 32 km in length and 23 km in width. In addition to Barra and Vatersay, nowadays the only inhabited islands of the group, there stretches to the south a further seven islands, the largest of which are Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Bemeray. A number of islands of differing sizes are scattered to the north-east of Barra, and the number of skerries and rocks varies with the tidal level. Barra's physical appearance is dominated by a chain of hills which cuts through the island from north-east to south-west, with the peaks of Heaval, Hartaval and An Sgala Mor all rising above 330 m. These mountains separate the rocky and indented east coast from the machair plains of the west. The chain of hills is continued in the islands south of Barra. Due to strong winter and spring gales the shore is subject to marine erosion, resulting in a ragged coastline with narrow inlets, caves and natural arches. Archaeological finds suggest that farming was established on Barra by 3000 BC, but as there is no linguistic evidence of a pre-Norse place names stratum the Norse immigration during the ninth century provides the earliest onomastic evidence. The Celtic cross-slab of Kilbar with its Norse ornaments and inscription is the first traceable source of any language spoken on Barra: IEptir porgerdu Steinars dottur es kross sja reistr', IAfter Porgero, Steinar's daughter, is this cross erected'(Close Brooks and Stevenson 1982:43). -

Outer Hebrides STAG Appraisal

Outer Hebrides STAG Appraisal Sound of Barra Exhibition Boards What is the study about? • A transport appraisal of the long-term options for the ferry routes to, from and within the Outer Hebrides, including the Sounds, was a commitment made in the Vessel Replacement & Deployment Plan (VRDP) annual report for 2015 • Peter Brett Associates LLP, now part of Stantec, has been commissioned by Transport Scotland to carry out this appraisal. The study is being informed and guided by a Reference Group, which is being led by Transport Scotland and includes Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, HITRANS, CMAL and CalMac Ferries Ltd • The appraisal will identify and evaluate options for the short, medium & long-term development of the Outer Hebrides network 2 Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (STAG) • The appraisal is being undertaken using a Transport Scotland process referred to as ‘STAG’, the approved guidance for the appraisal of potential transport projects • The principle of STAG is that it is objective-led rather than solution-led, ensuring that the option(s) ultimately taken forward address the identified transport problems and are the most appropriate when judged against a range of criteria • The study is at the Detailed Appraisal stage, and we are now seeking public & stakeholder views on the emerging outputs 3 What are we presenting today? • For the Sound of Barra route (Eriskay - Ardmhor), the following boards set out: • the transport problems & opportunities on the Sound of Barra route • the study ‘Transport Planning Objectives’ against which -

Hebrides Explorer

UNDISCOVERED HEBRIDES NORTHBOUND EXPLORER Self Drive and Cycling Tours Highlights Stroll the charming streets of Stornoway. Walk the Bird of Prey trail at Loch Seaforth. Spot Otters & Golden eagles. Visit the incredible Callanish standing stones. Explore Sea Caves at Garry Beach. See the white sands of Knockintorran beach Visit the Neolithic chambered cairn at Barpa Langais. Explore the iconic Kisimul Castle. View Barra Seals at Seal Bay. Walk amongst Wildflowers and orchids on the Vatersay Machair. Buy a genuine Harris Tweed and try a dapple of pure Hebridean whiskey. Explore Harris’s stunning hidden beaches and spot rare water birds. Walk through the hauntingly beautiful Scarista graveyard with spectacular views. This self-guided tour of the spectacular Outer Hebrides from the South to the North is offered as a self-drive car touring itinerary or Cycling holiday. At the extreme edge of Europe these islands are teeming with wildlife and idyllic beauty. Hebridean hospitality is renowned, and the people are welcoming and warm. Golden eagles, ancient Soay sheep, Otters and Seals all call the Hebrides home. Walk along some of the most alluring beaches in Britain ringed by crystal clear turquoise waters and gleaming white sands. Take a journey to the abandoned archipelago of St Kilda, now a world heritage site and a wildlife sanctuary and walk amongst its haunting ruins. With a flourishing arts and music scene, and a stunning mix of ancient neolithic ruins and grand castles, guests cannot fail to be enchanted by their visit. From South to North - this self-drive / cycling Holiday starts on Mondays, Thursdays or Saturdays from early May until late September. -

Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland

Wessex Archaeology Allasdale Dunes, Barra Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 65305 October 2008 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 65305.01 October 2008 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology and Ownership ......................1 1.3 Archaeological Background......................................................................2 Neolithic.......................................................................................................2 Bronze Age ...................................................................................................2 Iron Age........................................................................................................4 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work at Allasdale ............................................5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................6 -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

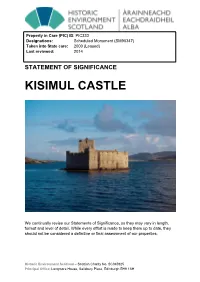

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

A Guided Wildlife Tour to St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides (Gemini Explorer)

A GUIDED WILDLIFE TOUR TO ST KILDA AND THE OUTER HEBRIDES (GEMINI EXPLORER) This wonderful Outer Hebridean cruise will, if the weather is kind, give us time to explore fabulous St Kilda; the remote Monach Isles; many dramatic islands of the Outer Hebrides; and the spectacular Small Isles. Our starting point is Oban, the gateway to the isles. Our sea adventure vessels will anchor in scenic, lonely islands, in tranquil bays and, throughout the trip, we see incredible wildlife - soaring sea and golden eagles, many species of sea birds, basking sharks, orca and minke whales, porpoises, dolphins and seals. Aboard St Hilda or Seahorse II you can do as little or as much as you want. Sit back and enjoy the trip as you travel through the Sounds; pass the islands and sea lochs; view the spectacular mountains and fast running tides that return. make extraordinary spiral patterns and glassy runs in the sea; marvel at the lofty headland lighthouses and castles; and, if you The sea cliffs (the highest in the UK) of the St Kilda islands rise want, become involved in working the wee cruise ships. dramatically out of the Atlantic and are the protected breeding grounds of many different sea bird species (gannets, fulmars, Our ultimate destination is Village Bay, Hirta, on the archipelago Leach's petrel, which are hunted at night by giant skuas, and of St Kilda - a UNESCO world heritage site. Hirta is the largest of puffins). These thousands of seabirds were once an important the four islands in the St Kilda group and was inhabited for source of food for the islanders. -

Greenland Barnacle 2003 Census Final

GREENLAND BARNACLE GEESE BRANTA LEUCOPSIS IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND: RESULTS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENSUS, MARCH 2003 WWT Report Authors Jenny Worden, Carl Mitchell, Oscar Merne & Peter Cranswick March 2004 Published by: The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucestershire GL2 7BT T 01453 891900 F 01453 891901 E [email protected] Reg. charity no. 1030884 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of WWT. This publication should be cited as: Worden, J, CR Mitchell, OJ Merne & PA Cranswick. 2004. Greenland Barnacle Geese Branta leucopsis in Britain and Ireland: results of the international census, March 2003 . The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge. gg CONTENTS Summary v 1 Introduction 6 2 Methods 7 3 Results 8 4 Discussion 13 4.1 Census total and accuracy 13 4.2 Long-term trend and distribution 13 4.3 Internationally and nationally important sites 17 4.4 Future recommendations 19 5 Acknowledgements 20 6 References 21 Appendices 22 ggg SUMMARY Between 1959 and 2003, eleven full international surveys of the Greenland population of Barnacle Geese have been conducted at wintering sites in Ireland and Scotland using a combination of aerial survey and ground counts. This report presents the results of the 2003 census, conducted between 27th and 31 March 2003 surveying a total of 323 islands and mainland sites along the west and north coasts of Scotland and Ireland. In Ireland, 30 sites were found to hold 9,034 Greenland Barnacle Geese and in Scotland, 35 sites were found to hold 47,256. -

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE Iseag 185 Mìle • 10 Island a Iles • S • 1 S • 2 M 0 Ei Rrie 85 Lea 2 Fe 1 Nan N • • Area 6 Causeways • 6 Cabhsi WELCOME

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE 185 Miles • 185 Mìl e • 1 0 I slan ds • 10 E ile an an WWW.HEBRIDEANWAY.CO.UK• 6 C au sew ays • 6 C abhsiarean • 2 Ferries • 2 Aiseag WELCOME A journey to the Outer Hebrides archipelago, will take you to some of the most beautiful scenery in the world. Stunning shell sand beaches fringed with machair, vast expanses of moorland, rugged hills, dramatic cliffs and surrounding seas all contain a rich biodiversity of flora, fauna and marine life. Together with a thriving Gaelic culture, this provides an inspiring island environment to live, study and work in, and a culturally rich place to explore as a visitor. The islands are privileged to be home to several award-winning contemporary Art Centres and Festivals, plus a creative trail of many smaller artist/maker run spaces. This publication aims to guide you to the galleries, shops and websites, where Art and Craft made in the Outer Hebrides can be enjoyed. En-route there are numerous sculptures, landmarks, historical and archaeological sites to visit. The guide documents some (but by no means all) of these contemplative places, which interact with the surrounding landscape, interpreting elements of island history and relationships with the natural environment. The Comhairle’s Heritage and Library Services are comprehensively detailed. Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle in Stornoway, by special loan from the British Museum, is home to several of the Lewis Chessmen, one of the most significant archaeological finds in the UK. Throughout the islands a network of local historical societies, run by dedicated volunteers, hold a treasure trove of information, including photographs, oral histories, genealogies, croft histories and artefacts specific to their locality. -

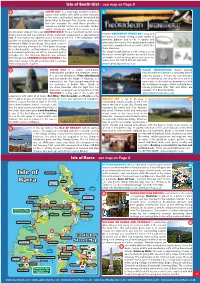

Isle of Barra - See Map on Page 8

Isle of South Uist - see map on Page 8 65 SOUTH UIST is a stunningly beautiful island of 68 crystal clear waters with white powder beaches to the west, and heather uplands dominated by Beinn Mhor to the east. The 20 miles of machair that runs alongside the sand dunes provides a marvellous habitat for the rare corncrake. Golden eagles, red grouse and red deer can be seen on the mountain slopes to the east. LOCHBOISDALE, once a major herring port, is the main settlement and ferry terminal on the island with a population of approximately Visit the HEBRIDEAN JEWELLERY shop and 300. A new marina has opened, and is located at the end of the breakwater with workshop at Iochdar, selling a wide variety of facilities for visiting yachts. Also newly opened Visitor jewellery, giftware and books of quality and Information Offi ce in the village. The island is one of good value for money. This quality hand crafted the last surviving strongholds of the Gaelic language jewellery is manufactured on South Uist in the in Scotland and the crofting industries of peat cutting Outer Hebrides. and seaweed gathering are still an important part of The shop in South Uist has a coffee shop close by everyday life. The Kildonan Museum has artefacts the beach, where light snacks are served. If you from this period. ASKERNISH GOLF COURSE is the are unable to visit our shop, please visit us on our oldest golf course in the Western Isles and is a unique online store. Tel: 01870 610288. HS8 5QX. -

W32 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

W32 bus time schedule & line map W32 Airdmhor View In Website Mode The W32 bus line (Airdmhor) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Airdmhor: 6:25 AM (2) Castlebay: 7:50 AM - 7:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest W32 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next W32 bus arriving. Direction: Airdmhor W32 bus Time Schedule 39 stops Airdmhor Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:25 AM Post O∆ce, Castlebay Tuesday 6:25 AM Craigard Hotel, Castlebay Wednesday 6:25 AM Ledaig Rd End, Castlebay Thursday 6:25 AM Garrygall Rd End, Castlebay Friday 6:25 AM Glen Rd End, Castlebay Saturday 6:25 AM Allt Cruachain, Brevig Number 137, Brevig W32 bus Info Road End, Brevig Direction: Airdmhor Stops: 39 Trip Duration: 26 min Cnoc A' Chonaisg, Leanish Line Summary: Post O∆ce, Castlebay, Craigard Hotel, Castlebay, Ledaig Rd End, Castlebay, Garrygall Township, Earsary Rd End, Castlebay, Glen Rd End, Castlebay, Allt Cruachain, Brevig, Number 137, Brevig, Road End, Township, Rhulios Brevig, Cnoc A' Chonaisg, Leanish, Township, Earsary, Township, Rhulios, Township, Balnabodach, Township, Balnabodach Northbay House, Balnabodach, Bruernish Rd End, Bogach, Turning Point, Bruernish, Junction, Northbay House, Balnabodach Bruernish, Heath Bank Hotel, Bogach, St Barr's Crescent, Bayherivagh, Church, Bayherivagh, Bruernish Rd End, Bogach Junction, Northbay, St Brendans Rd End, Castlebay, Vatersay Rd End, Castlebay, Township, Tangasdale, Turning Point, Bruernish Isle Of Barra Hotel, Tangasdale, Road -

CASTLEBAY COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting

CASTLEBAY COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of the meeting held in Castlebay School on Monday, 10 April at 19:00 PRESENT: Mìcheal Galbraith Chair Christina M ac Neil Vice-Chair Iain G M ac Neil Treasurer Marie M ac Leod Clerk Eoin M ac Neil Committee Marion M ac Neil Committee Donald Manford Councillor Geraldine Cowan (N0186) Police Officer Seonaidh Community APOLOGIES: Angus M ac Neil Committee Welcome Mìcheal Galbraith welcomed those in attendance. Matters Arising From Previous Minutes (Thursday, 24 November 2016) • Facebook Group: - This has been created since last our meeting; it was agreed that the group’s current privacy settings should be changed from ‘closed’ to ‘open’. It was further agreed that the Minutes should be uploaded to the group once they’ve been approved. • Litter Problem: - There is to be a meeting held this Wednesday in order to talk about how to tackle the bin and litter problem around the Co-op and by the football field. It was acknowledged that it was a positive start that they plan to meet up and tackle this issue. MG felt that it would be beneficial to attend the meeting. It was agreed that during the meeting it would be a good idea to request extra bins, particularly during the summer months; a notice on the bins would then be advisable in order to deter holidaymakers/campervans using the bins for their own use. It was also noted that if the area is maintained on a regular basis then it wouldn’t be such a problem. It was agreed that the Co-op can’t wash their hands of the issue and that they have to recognise their responsibility, it was felt that if they were to have, for example, a boxed in compound area for bins then that would go a long way in helping to tackle the issue.