Fieldwork Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldry Arms Granted to Members of the Macneil, Mcneill, Macneal, Macneile Families

Heraldry Arms granted to members of the MacNeil, McNeill, Macneal, MacNeile families The law of heraldry arms In Scotland all things armorial are governed by the laws of arms administered by the Court of the Lord Lyon. The origin of the office of Lord Lyon is shrouded in the mists of history, but various Acts of Parliament, especially those of 1592 and 1672 supplement the established authority of Lord Lyon and his brother heralds. The Lord Lyon is a great officer of state and has a dual capacity, both ministerial and judicial. In his ministerial capacity, he acts as heraldic advisor to the Sovereign, appoints messengers-at-arms, conducts national ceremony and grants arms. In his judicial role, he decides on questions of succession, authorizes the matriculation of arms, registers pedigrees, which are often used as evidence in the matter of succession to peerages, and of course judges in cases when the Procurator Fiscal prosecutes someone for the wrongful use of arms. A System of Heraldry Alexander Nisbet Published 1722 A classic standard heraldic treatise on heraldry, organized by armorial features used, and apparently attempting to list arms for every Scottish family, alive at the time or extinct. Nesbit quotes the source for most of the arms included in the treatis alongside the blazon A System of Heraldry is one of the most useful research sources for finding the armory of a Scots family. It is also the best readily available source discussing charges used in Scots heraldry . The Court of the Lord Lyon is the heraldic authority for Scotland and deals with all matters relating to Scottish Heraldry and Coats of Arms and maintains the Scottish Public Registers of Arms and Genealogies. -

Anke-Beate Stahl

Anke-Beate Stahl Norse in the Place-nam.es of Barra The Barra group lies off the west coast of Scotland and forms the southernmost extremity of the Outer Hebrides. The islands between Barra Head and the Sound of Barra, hereafter referred to as the Barra group, cover an area approximately 32 km in length and 23 km in width. In addition to Barra and Vatersay, nowadays the only inhabited islands of the group, there stretches to the south a further seven islands, the largest of which are Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Bemeray. A number of islands of differing sizes are scattered to the north-east of Barra, and the number of skerries and rocks varies with the tidal level. Barra's physical appearance is dominated by a chain of hills which cuts through the island from north-east to south-west, with the peaks of Heaval, Hartaval and An Sgala Mor all rising above 330 m. These mountains separate the rocky and indented east coast from the machair plains of the west. The chain of hills is continued in the islands south of Barra. Due to strong winter and spring gales the shore is subject to marine erosion, resulting in a ragged coastline with narrow inlets, caves and natural arches. Archaeological finds suggest that farming was established on Barra by 3000 BC, but as there is no linguistic evidence of a pre-Norse place names stratum the Norse immigration during the ninth century provides the earliest onomastic evidence. The Celtic cross-slab of Kilbar with its Norse ornaments and inscription is the first traceable source of any language spoken on Barra: IEptir porgerdu Steinars dottur es kross sja reistr', IAfter Porgero, Steinar's daughter, is this cross erected'(Close Brooks and Stevenson 1982:43). -

Outer Hebrides STAG Appraisal

Outer Hebrides STAG Appraisal Sound of Barra Exhibition Boards What is the study about? • A transport appraisal of the long-term options for the ferry routes to, from and within the Outer Hebrides, including the Sounds, was a commitment made in the Vessel Replacement & Deployment Plan (VRDP) annual report for 2015 • Peter Brett Associates LLP, now part of Stantec, has been commissioned by Transport Scotland to carry out this appraisal. The study is being informed and guided by a Reference Group, which is being led by Transport Scotland and includes Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, HITRANS, CMAL and CalMac Ferries Ltd • The appraisal will identify and evaluate options for the short, medium & long-term development of the Outer Hebrides network 2 Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (STAG) • The appraisal is being undertaken using a Transport Scotland process referred to as ‘STAG’, the approved guidance for the appraisal of potential transport projects • The principle of STAG is that it is objective-led rather than solution-led, ensuring that the option(s) ultimately taken forward address the identified transport problems and are the most appropriate when judged against a range of criteria • The study is at the Detailed Appraisal stage, and we are now seeking public & stakeholder views on the emerging outputs 3 What are we presenting today? • For the Sound of Barra route (Eriskay - Ardmhor), the following boards set out: • the transport problems & opportunities on the Sound of Barra route • the study ‘Transport Planning Objectives’ against which -

Campbell." Evidently His Was a Case of an Efficient, Kindly Officer Whose Lot Was Cast in Uneventful Lines

RECORDS of CLAN CAMPBELL IN THE MILITARY SERVICE OF THE HONOURABLE EAST INDIA COMPANY 1600 - 1858 COMPILED BY MAJOR SIR DUNCAN CAMPBELL OF BARCALDINE, BT. C. V.o., F.S.A. SCOT., F.R.G.S. WITH A FOREWORD AND INDEX BY LT.-COL. SIR RICHARD C. TEMPLE, BT. ~ C.B., C.I.E., F.S.A., V.P.R,A.S. LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. 4 NEW YORK, TORONTO> BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS r925 Made in Great Britain. All rights reserved. 'Dedicated by Permission TO HER- ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS LOUISE DUCHESS OF ARGYLL G.B.E., C.I., R.R.C. COLONEL IN CHIEF THE PRINCESS LOUISE'S ARGYLL & SUTHERLAND HIGHLANDERS THE CAMPBELLS ARE COMING The Campbells are cowing, o-ho, o-ho ! The Campbells are coming, o-ho ! The Campbells are coming to bonnie Loch leven ! The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! Upon the Lomonds I lay, I lay ; Upon the Lomonds I lay; I lookit down to bonnie Lochleven, And saw three perches play. Great Argyle he goes before ; He makes the cannons and guns to roar ; With sound o' trumpet, pipe and drum ; The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! The Camp bells they are a' in arms, Their loyal faith and truth to show, With banners rattling in the wind; The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! PREFACE IN the accompanying volume I have aimed at com piling, as far as possible, complete records of Campbell Officers serving under the H.E.I.C. -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

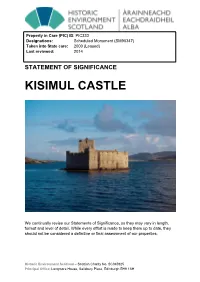

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

A Guided Wildlife Tour to St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides (Gemini Explorer)

A GUIDED WILDLIFE TOUR TO ST KILDA AND THE OUTER HEBRIDES (GEMINI EXPLORER) This wonderful Outer Hebridean cruise will, if the weather is kind, give us time to explore fabulous St Kilda; the remote Monach Isles; many dramatic islands of the Outer Hebrides; and the spectacular Small Isles. Our starting point is Oban, the gateway to the isles. Our sea adventure vessels will anchor in scenic, lonely islands, in tranquil bays and, throughout the trip, we see incredible wildlife - soaring sea and golden eagles, many species of sea birds, basking sharks, orca and minke whales, porpoises, dolphins and seals. Aboard St Hilda or Seahorse II you can do as little or as much as you want. Sit back and enjoy the trip as you travel through the Sounds; pass the islands and sea lochs; view the spectacular mountains and fast running tides that return. make extraordinary spiral patterns and glassy runs in the sea; marvel at the lofty headland lighthouses and castles; and, if you The sea cliffs (the highest in the UK) of the St Kilda islands rise want, become involved in working the wee cruise ships. dramatically out of the Atlantic and are the protected breeding grounds of many different sea bird species (gannets, fulmars, Our ultimate destination is Village Bay, Hirta, on the archipelago Leach's petrel, which are hunted at night by giant skuas, and of St Kilda - a UNESCO world heritage site. Hirta is the largest of puffins). These thousands of seabirds were once an important the four islands in the St Kilda group and was inhabited for source of food for the islanders. -

Greenland Barnacle 2003 Census Final

GREENLAND BARNACLE GEESE BRANTA LEUCOPSIS IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND: RESULTS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENSUS, MARCH 2003 WWT Report Authors Jenny Worden, Carl Mitchell, Oscar Merne & Peter Cranswick March 2004 Published by: The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucestershire GL2 7BT T 01453 891900 F 01453 891901 E [email protected] Reg. charity no. 1030884 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of WWT. This publication should be cited as: Worden, J, CR Mitchell, OJ Merne & PA Cranswick. 2004. Greenland Barnacle Geese Branta leucopsis in Britain and Ireland: results of the international census, March 2003 . The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge. gg CONTENTS Summary v 1 Introduction 6 2 Methods 7 3 Results 8 4 Discussion 13 4.1 Census total and accuracy 13 4.2 Long-term trend and distribution 13 4.3 Internationally and nationally important sites 17 4.4 Future recommendations 19 5 Acknowledgements 20 6 References 21 Appendices 22 ggg SUMMARY Between 1959 and 2003, eleven full international surveys of the Greenland population of Barnacle Geese have been conducted at wintering sites in Ireland and Scotland using a combination of aerial survey and ground counts. This report presents the results of the 2003 census, conducted between 27th and 31 March 2003 surveying a total of 323 islands and mainland sites along the west and north coasts of Scotland and Ireland. In Ireland, 30 sites were found to hold 9,034 Greenland Barnacle Geese and in Scotland, 35 sites were found to hold 47,256. -

Clan Macneil Association of America

Clan MacNeil Association of Australia Newsletter for clan members and friends. December 2010 Editor - John McNeil 21 Laurel Avenue, Linden Park, SA 5065 telephone 08 83383858 Items is this newsletter – more information for her from Calum MacNeil, • Welcome to new members genealogist on Barra. • Births, marriages and deaths • National clan gathering in Canberra Births, Marriages and Deaths • World clan gathering on Barra Aug. On 2 nd October John McNeil married Lisa van 2010 Grinsven at the Bird in hand winery in the • News from Barra Adelaide hills • Lunch with Cliff McNeil & Bob Neil • Jean Buchanan & John Whiddon at Daylesford highland gathering • Reintroduction of beavers to Knapdale • Proposal for a clan young adult program • Recent events • Coming events • Additions to our clan library • An update of the research project of the McNeill / MacNeil families living in Argyll 1400 -1800 AD • Clan MacNeil merchandise available to you • Berneray one of the Bishop’s isles south John is the son of Peter and Mary and grandson of Barra of Ronald McNeil, my cousin. He represents the fifth generation of a John McNeil in our family. Please join with me in congratulating them on New Members their marriage. I would like to welcome our new clan members who have joined since the last newsletter. We offer our deepest sympathy to Cliff McNeil Mary Surman on the death of his mother, Helen Mary McNeil Carol & John Searcy who died on 8 th November 2010, age 96 years. Phillip Draper Helen was a member of the committee for the Clan MacNeil Association of Australia in its Over recent months I have met with John early days in Sydney. -

A Adhamhar Foltchaion, 6. Aedhan Glas, Son of N Uadhas, 4. Aefa

INDEX A Aula£ the White, King of the Danes, 22. Adhamhar Foltchaion, 6. Auldearn, Battle of, 123. Aedhan Glas, son of N uadhas, 4. Aefa, daughter of Alpin, 9. B Agnomain, 1. Agnon, Fionn, 1. Bachca (Lorne), battle at, 58. Aileach, Fortress of, 14, 15. Badhbhchadh, 5. Ailill, son of Eochaidh, 12. Baile Thangusdail (Barra), 179. Aitlin, 4. Baine, daughter of Seal Balbh, 8. Airer Gaedhil (see ARGYLL). Baliol, Edward, 40. - Aithiochta, wife of Feargal IX, 19. Bannockburn, Battle of, 40. Alba (Scotland), 13. Baoth, 1. Alexander II, King of Scotland, 38. Bar, Barony of, Kintyre, 40. Alexander III, King of Scotland, 38. Barra, origin of name, 26, 150 et Alladh, 1. seq.; Allan, son of Ruari, 39. description, 167, 174, 179 et seq.; Allan nan Sop, (see ALLAN MAC- settled by the Macneils, 24; LEAN OF GrGHA). Charters, 42, 45, 83, 99; A11en, Battle of, 19. Norse occupation, 27-32 (see Alpin, King of the Picts, 9. Norsemen) ; America, Emigration to, 90, 93, 122, under Lordship of the Isles, 39, 133 et seq., 206, 207, 210. 41; Ancrum Moor, Battle of, 100. sale of, 137; Angus Og, son of John of the Isles, brooches, 28-31; 45. religion, 145 et seq. (see MAc A11n Ja11e, wreck of the, 195. NEIL). Antigonish, settlement at, 136. "Barra Song," 25. Aodh Aonrachan, 41. "Barra Register," quoted, 25, 33. Aodh, son of Aodh Aonrachan XX, Barton, Robert, 49. 24. Baruma, The (a tax), 19. Aoife, wife of Fiacha, 10. Battle customs, 161-164. Aongus Olmucach, 4. Bealgadain, Battle of, 4. Aongus Tuirneach-Teamrach, son of Bearnera, Isle, (see Berne ray). -

Clan Macneil Association of New Zealand

Clan MacNeil Association of New Zealand September 2009 Newsletter: Failte – Welcome Welcome to the September edition, of the Clan MacNeil newsletter. Thanks to all those who have helped contribute content— keep it up. Tartan Day Celebrations Waikato - Bay of Plenty Clan Associations cele- brated Tartan Day on The 4th July at Tauranga. The day hosted by Clan Cameron was atttended by about 100 members from Waikato, the Bay of Plenty coming from as far away as Taumaranui. Clan MacNeil attendees were Pat Duncan, Judith Bean and new member Heather Peart. ―The rain held off for a very short march from a College field across the road into the Wesley Church Hall where the function was held. After the piping in of the Banners each Clan representative was invited to speak on behalf of their Clan which I duly did passing on greetings from Clan McNeil” said MacNeil participant Pat Duncan.‖ ―Ted Little our usual representative to this function was unable to attend and sent his apologies. Clan Cameron Chief gave a short speech outlining the outlawing of The Tartan and its reinstatement” added Duncan. Clans represented were; Clan Cameron, David- son, McArthur, Wallace, Gordon, Johnston (accompanied by their little granddaughters). McLoughlan, Donnachaidh and Stewart. Jessica McLachland danced having just returned The coffee cart did a great trade in the break be- from attending Homecoming Scotland with her fore the Haggis was piped in.The Address given grandfather, Dave, who also sang a selection of and attendees all participated in a wee dram (or songs with 3 others. Attendees were all invited to juice ) to toast the Haggis. -

The Scottish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1968 The cottS ish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War Nelson Orion Westphal Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Westphal, Nelson Orion, "The cS ottish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War" (1968). Masters Theses. 4157. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4157 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #3 To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced