The Relevance of Kant's Objection to Anselm's Ontological Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Existence in Physics

Existence in Physics Armin Nikkhah Shirazi ∗ University of Michigan, Department of Physics, Ann Arbor January 24, 2019 Abstract This is the second in a two-part series of papers which re-interprets relativistic length contraction and time dilation in terms of concepts argued to be more fundamental, broadly construed to mean: concepts which point to the next paradigm. After refining the concept of existence to duration of existence in spacetime, this paper introduces a criterion for physi- cal existence in spacetime and then re-interprets time dilation in terms of the concept of the abatement of an object’s duration of existence in a given time interval, denoted as ontochronic abatement. Ontochronic abatement (1) focuses attention on two fundamental spacetime prin- ciples the significance of which is unappreciated under the current paradigm, (2) clarifies the state of existence of speed-of-light objects, and (3) leads to the recognition that physical existence is an equivalence relation by absolute dimensionality. These results may be used to justify the incorporation of the physics-based study of existence into physics as physical ontology. Keywords: Existence criterion, spacetime ontic function, ontochronic abatement, invariance of ontic value, isodimensionality, ontic equivalence class, areatime, physical ontology 1 Introduction This is the second in a two-part series of papers which re-interprets relativistic length contraction and time dilation in terms of concepts argued to be more fundamental, broadly construed to mean: concepts which point to the next paradigm. The first paper re-conceptualized relativistic length contraction in terms of dimensional abatement [1], and this paper will re-conceptualize relativistic time dilation in terms of what I will call ontochronic abatement, to be defined as the abatement of an object’s duration of existence within a given time interval. -

Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History

religions Article Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History Enrico Beltramini Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, CA 94002, USA; [email protected] Abstract: How to deal with religious ideas in religious history (and in history in general) has recently become a matter of discussion. In particular, a number of authors have framed their work around the concept of ‘sacramental ontology,’ that is, a unified vision of reality in which the secular and the religious come together, although maintaining their distinction. The authors’ choices have been criticized by their fellow colleagues as a form of apologetics and a return to integralism. The aim of this article is to provide a proper context in which to locate the phenomenon of sacramental ontology. I suggest considering (1) the generation of the concept of sacramental ontology as part of the internal dialectic of the Christian intellectual world, not as a reaction to the secular; and (2) the adoption of the concept as a protection against ontological nihilism, not as an attack on scientific knowledge. Keywords: sacramental ontology; history; dualism; immanentism; nihilism Citation: Beltramini, Enrico. 2021. Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History. Religions 12: 47. https://doi.org/ 1. Introduction 10.3390rel12010047 A specter is haunting the historical enterprise, the specter of ‘sacramental ontology.’ Received: 3 December 2020 The specter of sacramental ontology is carried by a generation of Roman Catholic and Accepted: 23 December 2020 Evangelical historians as well as historical theologians who aim to restore the sacred dimen- 1 Published: 11 January 2021 sion of nature. -

On the Logic of the Ontological Argument∗ X

Paul E. Oppenheimer and Edward N. Zalta 2 by `9y(y =x)' and the claim that x has the property of existence by `E!x'. That is, we represent the difference between the two claims by exploiting the distinction between quantifying over x and predicating existence of On the Logic of the Ontological Argument∗ x. We shall sometimes refer to this as the distinction between the being of x and the existence of x. Thus, instead of reading Anselm as having discovered a way of inferring God's actuality from His mere possibility, Paul E. Oppenheimer we read him as having discovered a way of inferring God's existence from Thinking Machines Corporation His mere being. Another important feature of our reading concerns the fact that we and take the phrase \that than which none greater can be conceived" seriously. Certain inferences in the ontological argument are intimately linked to the logical behavior of this phrase, which is best represented as a definite Edward N. Zalta description.3 If we are to do justice to Anselm's argument, we must not Philosophy Department syntactically eliminate descriptions the way Russell does. One of the Stanford University highlights of our interpretation is that a very simple inference involving descriptions stands at the heart of the argument.4 Saint Anselm of Canterbury offered several arguments for the existence The Language and Logic Required for the Argument of God. We examine the famous ontological argument in Proslogium ii. Many recent authors have interpreted this argument as a modal one.1 But We shall cast our new reading in a standard first-order language. -

KANT's Religious Argument for the Existence OF

Kant’S REliGioUS ARGUMEnt for thE EXistENCE of God: THE UltiMatE DEPEndENCE of HUMan DEstiny on DivinE AssistanCE Stephen R. Palmquist After reviewing Kant’s well-known criticisms of the traditional proofs of God’s existence and his preferred moral argument, this paper presents a de- tailed analysis of a densely-packed theistic argument in Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason. Humanity’s ultimate moral destiny can be fulfilled only through organized religion, for only by participating in a religious community (or “church”) can we overcome the evil in human nature. Yet we cannot conceive how such a community can even be founded without presupposing God’s existence. Viewing God as the internal moral lawgiv- er, empowering a community of believers, is Kant’s ultimate rationale for theistic belief. I. The Practical Orientation of Kantian Theology Kant is well known for attacking three traditional attempts to prove God’s existence: the ontological, cosmological and physico-theological (or teleological) arguments. All such “theoretical” arguments inevita- bly fail, he claimed, because their aim (achieving certain knowledge of God’s existence) transcends the capabilities of human reason. Viewed from the theoretical standpoint, God is not an object of possible human knowledge, but an idea that inevitably arises as a by-product of the to- talizing tendencies of human reason. The very process of obtaining em- pirical knowledge gives rise to the concept “God,” and this enables us to think and reason about what God’s nature must be if God exists; yet we have no “intuition” of God (neither through sensible input nor in any “pure” form), so we can have no reasonable hope of obtaining theoretical knowledge of God’s existence. -

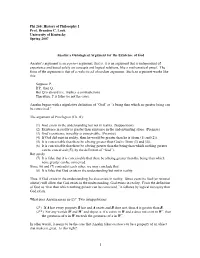

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

Divine Utilitarianism

Liberty University DIVINE UTILITARIANISM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Masters of Arts in Philosophical Studies By Jimmy R. Lewis January 16, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One: Introduction ……………………………...……………..……....3 Statement of the Problem…………………………….………………………….3 Statement of the Purpose…………………………….………………………….5 Statement of the Importance of the Problem…………………….……………...6 Statement of Position on the Problem………………………...…………….......7 Limitations…………………………………………….………………………...8 Development of Thesis……………………………………………….…………9 Chapter Two: What is meant by “Divine Utilitarianism”..................................11 Introduction……………………………….…………………………………….11 A Definition of God.……………………………………………………………13 Anselm’s God …………………………………………………………..14 Thomas’ God …………………………………………………………...19 A Definition of Utility .…………………………………………………………22 Augustine and the Good .……………………………………………......23 Bentham and Mill on Utility ……………………………………………25 Divine Utilitarianism in the Past .……………………………………………….28 New Divine Utilitarianism .……………………………………………………..35 Chapter Three: The Ethics of God ……………………………………………45 Divine Command Theory: A Juxtaposition .……………………………………45 What Divine Command Theory Explains ………………….…………...47 What Divine Command Theory Fails to Explain ………………………47 What Divine Utilitarianism Explains …………………………………………...50 Assessing the Juxtaposition .…………………………………………………....58 Chapter Four: Summary and Conclusion……………………………………...60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..64 2 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Statement of the -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

Why Determinism in Physics Has No Implications for Free Will

Why determinism in physics has no implications for free will Michael Esfeld University of Lausanne, Department of Philosophy [email protected] (draft 8 October 2017) (paper for the conference “Causality, free will, divine action”, Vienna, 12 to 15 Sept. 2017) Abstract This paper argues for the following three theses: (1) There is a clear reason to prefer physical theories with deterministic dynamical equations: such theories are both maximally simple and maximally rich in information, since given an initial configuration of matter and the dynamical equations, the whole (past and future) evolution of the configuration of matter is fixed. (2) There is a clear way how to introduce probabilities in a deterministic physical theory, namely as answer to the question of what evolution of a specific system we can reasonably expect under ignorance of its exact initial conditions. This procedure works in the same manner for both classical and quantum physics. (3) There is no cogent reason to subscribe to an ontological commitment to the parameters that enter the (deterministic) dynamical equations of physics. These parameters are defined in terms of their function for the evolution of the configuration of matter, which is defined in terms of relative particle positions and their change. Granting an ontological status to them does not lead to a gain in explanation, but only to artificial problems. Against this background, I argue that there is no conflict between determinism in physics and free will (on whatever conception of free will), and, in general, point out the limits of science when it comes to the central metaphysical issues. -

An Introduction to Relational Ontology Wesley J

An Introduction to Relational Ontology Wesley J. Wildman, Boston University, May 15, 2006 There is a lot of talk these days about relational ontology. It appears in theology, philosophy, psychology, political theory, educational theory, and even information science. The basic contention of a relational ontology is simply that the relations between entities are ontologically more fundamental than the entities themselves. This contrasts with substantivist ontology in which entities are ontologically primary and relations ontologically derivative. Unfortunately, there is persistent confusion in almost all literature about relational ontology because the key idea of relation remains unclear. Once we know what relations are, and indeed what entities are, we can responsibly decide what we must mean, or what we can meaningfully intend to mean, by the phrase “relational ontology.” Why Do Philosophers Puzzle over Relations? Relations are an everyday part of life that most people take for granted. We are related to other people and to the world around us, to our political leaders and our economic systems, to our children and to ourselves. There are logical, emotional, physical, mechanical, technological, cultural, moral, sexual, aesthetic, logical, and imaginary relations, to name a few. There is no particular problem with any of this for most people. Philosophers have been perpetually puzzled about relations, however, and they have tried to understand them theoretically and systematically. Convincing philosophical theories of relations have proved extraordinarily difficult to construct for several reasons. First, the sheer variety of relations seems to make the category of “relation” intractable. Philosophers have often tried to use simple cases as guides to more complex situations but how precisely can this method work in the case of relations? Which relations are simple or basic, and which complex or derivative? If we suppose that the simplest relations are those analyzable in physics, we come across a second problem. -

Gce a Level Marking Scheme

GCE A LEVEL MARKING SCHEME SUMMER 2018 A LEVEL RELIGIOUS STUDIES - COMPONENT 2 PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION A120U20-1 © WJEC CBAC Ltd. INTRODUCTION This marking scheme was used by WJEC for the 2018 examination. It was finalised after detailed discussion at examiners' conferences by all the examiners involved in the assessment. The conference was held shortly after the paper was taken so that reference could be made to the full range of candidates' responses, with photocopied scripts forming the basis of discussion. The aim of the conference was to ensure that the marking scheme was interpreted and applied in the same way by all examiners. It is hoped that this information will be of assistance to centres but it is recognised at the same time that, without the benefit of participation in the examiners' conference, teachers may have different views on certain matters of detail or interpretation. WJEC regrets that it cannot enter into any discussion or correspondence about this marking scheme. © WJEC CBAC Ltd. Marking guidance for examiners, please apply carefully and consistently: Positive marking It should be remembered that candidates are writing under examination conditions and credit should be given for what the candidate writes, rather than adopting the approach of penalising him/her for any omissions. It should be possible for a very good response to achieve full marks and a very poor one to achieve zero marks. Marks should not be deducted for a less than perfect answer if it satisfies the criteria of the mark scheme. Exemplars in the mark scheme are only meant as helpful guides.