Redalyc.The Necromancer Friar Bacon in the Magic World Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magic and the Supernatural

Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Magic and the Supernatural At the Interface Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E An At the Interface research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/at-the-interface/ The Evil Hub ‘Magic and the Supernatural’ 2012 Magic and the Supernatural Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-095-5 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table of Contents Preface vii Scott Hendrix PART 1 Philosophy, Religion and Magic Magic and Practical Agency 3 Brian Feltham Art, Love and Magic in Marsilio Ficino’s De Amore 9 Juan Pablo Maggioti The Jinn: An Equivalent to Evil in 20th Century 15 Arabian Nights and Days Orchida Ismail and Lamya Ramadan PART 2 Magic and History Rational Astrology and Empiricism, From Pico to Galileo 23 Scott E. -

Echoes of Legend: Magic As the Bridge Between a Pagan Past And

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2018 Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur Josh Mangle Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mangle, Josh, "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur" (2018). Graduate Theses. 84. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECHOES OF LEGEND: MAGIC AS THE BRIDGE BETWEEN A PAGAN PAST AND A CHRISTIAN FUTURE IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts In English Winthrop University May 2018 By Josh Mangle ii Abstract Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur is a text that tells the story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Malory wrote this tale by synthesizing various Arthurian sources, the most important of which being the Post-Vulgate cycle. Malory’s work features a division between the Christian realm of Camelot and the pagan forces trying to destroy it. -

Black Magic & White Supremacy

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2-23-2021 Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power Nicholas Charles Peters Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Peters, Nicholas Charles, "Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 962. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power By Nicholas Charles Peters An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in English and University Honors Thesis Adviser Dr. Michael Clark Portland State University 2021 1 “Being burned at the stake was an empowering experience. There are secrets in the flames, and I came back with more than a few” (Head 19’15”). Burning at the stake is one of the first things that comes to mind when thinking of witchcraft. Fire often symbolizes destruction or cleansing, expelling evil or unnatural things from creation. “Fire purges and purifies... scatters our enemies to the wind. -

Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-Sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices

Article Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices Ronald M. Davidson Department of Religious Studies, Farifield University, Fairfield, CT 06824, USA; [email protected] Received: 27 June 2017; Accepted: 23 August 2017; Published: 13 September 2017 Abstract: Most models on the origins of tantrism have been either inattentive to or dismissive of non-literate, non-sectarian ritual systems. Groups of magicians, sorcerers or witches operated in India since before the advent of tantrism and continued to perform ritual, entertainment and curative functions down to the present. There is no evidence that they were tantric in any significant way, and it is not clear that they were concerned with any of the liberation ideologies that are a hallmark of the sectarian systems, even while they had their own separate identities and specific divinities. This paper provides evidence for the durability of these systems and their continuation as sources for some of the ritual and nomenclature of the sectarian tantric traditions, including the predisposition to ritual creativity and bricolage. Keywords: tantra; mantra; ritual; magician; sorcerer; seeress; vidyādhara; māyākāra; aindrajālika; non-literate 1. Introduction1 In the emergence of alternative religious systems such as tantrism, a number of factors have historically been seen at play. Among these are elements that might be called ‘pre-existing’. That is, they themselves are not representative of the eventual emergent system, but they provide some of the raw material—ritual, ideological, terminological, functional, or other—for its development. Indology, and in particular the study of Indian ritual, has been less than adroit at discussing such phenomena, especially when it may be designated or classified as ‘magical’ in some sense. -

SOURCES of MEDIEVAL DEMONOLOGY by Diana Lynn Walzel When Most of Us Think of Demons Today, If We Do Think of Them, Some Medieval Imp Undoubtedly Comes to Mind

SOURCES OF MEDIEVAL DEMONOLOGY by Diana Lynn Walzel When most of us think of demons today, if we do think of them, some medieval imp undoubtedly comes to mind. The lineage of the medieval demon, and the modern conception thereof, can be traced to four main sources, all of which have links to the earliest human civilizations. Greek philosophy, Jewish apocryphal literature, Biblical doctrine, and pagan Germanic folklore all contribute elements to the demons which flourished in men's minds at the close of the medieval period. It is my purpose briefly to delineate the demonology of each of these sources and to indicate their relationship to each other. Homer had equated demons with gods and used daimon and theos as synonyms. Later writers gave a different nuance and even definition to the word daimon, but the close relationship between demons and the gods was never completely lost from sight. In the thinkers of Middle Platonism the identification of demons with the gods was revived, and this equation is ever-present in Christian authors. Hesiod had been the first to view demons as other than gods, consider- ing them the departed souls of men living in the golden age. Going a step further, Pythagoras believed the soul of any man became a demon when separated from the body. A demon, then, was simply a bodiless soul. In Platonic thought there was great confusion between demons and human souls. There seems to have been an actual distinction between the two for Plato, but what the distinction was is impossible now to discern. -

Meike Weijtmans S4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: Dr

Weijtmans, s4235797/1 Meike Weijtmans s4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: dr. Chris Cusack Examiner: dr. L.S. Chardonnens August 15, 2018 The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend M.A.S. Weijtmans BA Thesis August 15, 2018 Weijtmans, s4235797/2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: dr. Chris Cusack, dr. L.S. Chardonnens Title of document: The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend Name of course: BA Thesis Date of submission: August 15, 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Meike Weijtmans Student number: s4235797 Weijtmans, s4235797/3 Abstract Celtic culture has always been a source of interest in contemporary popular culture, as it has been in the past; Greek and Roman writers painted the Celts as barbaric and uncivilised peoples, but were impressed with their religion and mythology. The Celtic revival period gave birth to the paradox that still defines the Celtic image to this day, namely that the rurality, simplicity and spirituality of the Celts was to be admired, but that they were uncivilised, irrational and wild at the same time. Recent debates surround the concepts of “Celt”, “Celticity” and “Celtic” are also discussed in this thesis. The first part of this thesis focuses on Celtic history and culture, as well as the complexities surrounding the terminology and the construction of the Celtic image over the centuries. This main body of the thesis analyses the way Celtic elements in contemporary adaptations of the Arthurian narrative form the modern Celtic image. -

Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K

Volume 39 Number 2 Article 2 4-23-2021 Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle Oleksandra Filonenko Petro Mohyla Black Sea National University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Recommended Citation Filonenko, Oleksandra (2021) "Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 39 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract In my article, I discuss a peculiar connection between the persisting ideas about magic in the Western world and Ursula Le Guin's magical world in the Earthsea universe and its evolution over the decades. -

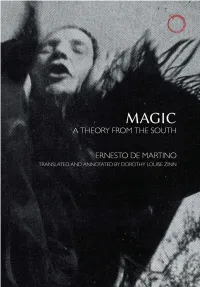

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Magic & Witchcraft in Africa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kohnert, Dirk Article — Accepted Manuscript (Postprint) Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa World Development Suggested Citation: Kohnert, Dirk (1996) : Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa, World Development, ISSN 0305-750X, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 24, Iss. 8, pp. 1347-1355, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00045-9 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118614 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Authors version – published in: World Development, vol. 24, No. 8, 1996, pp. 1347-1355 Magic and Witchcraft Implications for Democratization and Poverty-Alleviating Aid in Africa Dirk Kohnert 1) Abstract The belief in occult forces is still deeply rooted in many African societies, regardless of education, religion, and social class of the people concerned. -

Cunning Folk and Wizards in Early Modern England

Cunning Folk and Wizards In Early Modern England University ID Number: 0614383 Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of MA in Religious and Social History, 1500-1700 at the University of Warwick September 2010 This dissertation may be photocopied Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 1 Who Were White Witches and Wizards? 8 Origins 10 OccupationandSocialStatus 15 Gender 20 2 The Techniques and Tools of Cunning Folk 24 General Tools 25 Theft/Stolen goods 26 Love Magic 29 Healing 32 Potions and Protection from Black Witchcraft 40 3 Higher Magic 46 4 The Persecution White Witches Faced 67 Law 69 Contemporary Comment 74 Conclusion 87 Appendices 1. ‘Against VVilliam Li-Lie (alias) Lillie’ 91 2. ‘Popular Errours or the Errours of the people in matter of Physick’ 92 Bibliography 93 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my undergraduate and postgraduate tutors at Warwick, whose teaching and guidance over the years has helped shape this dissertation. In particular, a great deal of gratitude goes to Bernard Capp, whose supervision and assistance has been invaluable. Also, to JH, GH, CS and EC your help and support has been beyond measure, thank you. ii Cunning folk and Wizards in Early Modern England Witchcraft has been a reoccurring preoccupation for societies throughout history, and as a result has inspired significant academic interest. The witchcraft persecutions of the early modern period in particular have received a considerable amount of historical investigation. However, the vast majority of this scholarship has been focused primarily on the accusations against black witches and the punishments they suffered. -

Complete Book of Necromancers by Steve Kurtz

2151 ® ¥DUNGEON MASTER® Rules Supplement Guide The Complete Book of Necromancers By Steve Kurtz ª Table of Contents Introduction Bodily Afflictions How to Use This Book Insanity and Madness Necromancy and the PC Unholy Compulsions What You Will Need Paid In Full Chapter 1: Necromancers Chapter 4: The Dark Art The Standard Necromancer Spell Selection for the Wizard Ability Scores Criminal or Black Necromancy Race Gray or Neutral Necromancy Experience Level Advancement Benign or White Necromancy Spells New Wizard Spells Spell Restrictions 1st-Level Spells Magic Item Restrictions 2nd-Level Spells Proficiencies 3rd-Level Spells New Necromancer Wizard Kits 4th-Level Spells Archetypal Necromancer 5th-Level Spells Anatomist 6th-Level Spells Deathslayer 7th-Level Spells Philosopher 8th-Level Spells Undead Master 9th-Level Spells Other Necromancer Kits Chapter 5: Death Priests Witch Necromantic Priesthoods Ghul Lord The God of the Dead New Nonweapon Proficiencies The Goddess of Murder Anatomy The God of Pestilence Necrology The God of Suffering Netherworld Knowledge The Lord of Undead Spirit Lore Other Priestly Resources Venom Handling Chapter 6: The Priest Sphere Chapter 2: Dark Gifts New Priest Spells Dual-Classed Characters 1st-Level Spells Fighter/Necromancer 2nd-Level Spells Thief / Necromancer 3rd-Level Spells Cleric/Necromancer 4th-Level Spells Psionicist/Necromancer 5th-Level Spells Wild Talents 6th-Level Spells Vile Pacts and Dark Gifts 7th-Level Spells Nonhuman Necromancers Chapter 7: Allies Humanoid Necromancers Apprentices Drow Necromancers -

The Punishment of Clerical Necromancers During the Period 1100-1500 CE

Christendom v. Clericus: The Punishment of Clerical Necromancers During the Period 1100-1500 CE A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Kayla Marie McManus-Viana In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for the Bachelor of Science in History, Technology, and Society with the Research Option Georgia Institute of Technology December 2020 1 Table of Contents Section 1: Abstract Section 2: Introduction Section 3: Literature Review Section 4: Historical Background Magic in the Middle Ages What is Necromancy? Clerics as Sorcerers The Catholic Church in the Middle Ages The Law and Magic Section 5: Case Studies Prologue: Magic and Rhetoric The Cases Section 6: Conclusion Section 7: Bibliography 3 Abstract “The power of Christ compels you!” is probably the most infamous line from the 1973 film The Exorcist. The movie, as the title suggests, follows the journey of a priest as he attempts to excise a demon from within the body of a young girl. These types of sensational pop culture depictions are what inform the majority of people’s conceptions of demons and demonic magic nowadays. Historically, however, human conceptions of demons and magic were more nuanced than those depicted in The Exorcist and similar works. Demons were not only beings to be feared but sources of power to be exploited. Necromancy, a form of demonic magic, was one avenue in which individuals could attempt to gain control over a demon. During the period this thesis explores, 1100-1500 CE, only highly educated men, like clerics, could complete the complicated rituals associated with necromancy. Thus, this study examines the rise of the learned art of clerical necromancy in conjunction with the re-emergence of higher learning in western Europe that developed during the period from 1100-1500 CE.