Currency and the Economy in Tudor and Early Stuart England by C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malton Antique Sale

Boulton & Cooper MALTON ANTIQUE SALE WEDNESDAY 22ND OCTOBER AT 10.00am At The Milton Rooms, Market Place, Malton, North Yorkshire. YO17 7LX VIEWING: Tuesday 21st October 10.00am – 7.00pm & on morning of sale from 9.00am REQUESTS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION OR IMAGES SHOULD BE RECEIVED BY US NO LATER THAN 1PM THE DAY BEFORE THE SALE China 1 – 48 Glassware 49 – 65 Metalware 66 – 80 Books 81 – 99 Platedware & Silver 100 - 128 Jewellery 129 – 206 Coins, Banknotes & Token 207 – 372 Stamps 373 – 403 Collector’s Items 404 – 492 Pictures & Prints 493 – 521 Clocks & Barometers 522 – 526 Carpets & Rugs 527 – 533 Furniture 534 – 590 CHINA 1. A Royal Doulton Character Jug 'Winston Churchill', 9" (23cms) high and a Doulton tobacco set comprising cigarette box (cover missing) and five small oblong dishes decorated with hounds and foxes (one chipped). £40-60 2. A Cantonese Plate decorated with panels of figures and flowers, 10" (26cms) diameter, an Imari pattern plate, two ginger jars and three other Oriental plates. £30-40 3. Six Royal Crown Derby Coffee Cans and Saucers (one cup a/f), 19th Century Masons Ironstone plate, two other plates and a small Dresden oval box and cover. £30-40 4. A Paragon Cup, Saucer and Plate commemorating the Coronation of Edward VIII and a similar George VI coronation cup. £10-20 5. A Royal Doulton Character Jug 'Gondolier' DH6589, large size. £50-70 6. A set of twelve Royal Worcester 'Months of the Year' figures of children, modelled by F C Doughty. (June & November damaged). £400-500 7. An English Delft oval Meat Plate decorated with Oriental landscapes in blue and white. -

The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864

1 Constructing Ionian Identities: The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864 Maria Paschalidi Department of History University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to University College London 2009 2 I, Maria Paschalidi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Utilising material such as colonial correspondence, private papers, parliamentary debates and the press, this thesis examines how the Ionian Islands were defined by British politicians and how this influenced various forms of rule in the Islands between 1815 and 1864. It explores the articulation of particular forms of colonial subjectivities for the Ionian people by colonial governors and officials. This is set in the context of political reforms that occurred in Britain and the Empire during the first half of the nineteenth-century, especially in the white settler colonies, such as Canada and Australia. It reveals how British understandings of Ionian peoples led to complex negotiations of otherness, informing the development of varieties of colonial rule. Britain suggested a variety of forms of government for the Ionians ranging from authoritarian (during the governorships of T. Maitland, H. Douglas, H. Ward, J. Young, H. Storks) to representative (under Lord Nugent, and Lord Seaton), to responsible government (under W. Gladstone’s tenure in office). All these attempted solutions (over fifty years) failed to make the Ionian Islands governable for Britain. The Ionian Protectorate was a failed colonial experiment in Europe, highlighting the difficulties of governing white, Christian Europeans within a colonial framework. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

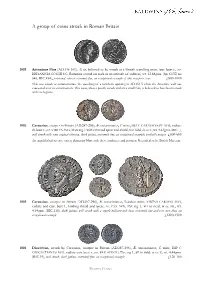

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

Royal Mint Trading Fund

Royal Mint Trading Fund Annual Report and Accounts 2014-15 Royal Mint Trading Fund | Annual Report and Accounts 2014-15 2 Royal Mint Trading Fund Annual Report and Accounts 2014-15 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 4(6) of the Government Trading Funds Act 1973 as amended by the Government Trading Act 1990 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 16 July 2015 HC 161 © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: psi@ nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/ publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or email: [email protected]. Print ISBN 9781474120913 Web ISBN 9781474120920 ID 04061511 06/15 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Contents 05 Accounting Officer’s Statement 06 Report of the Chief Executive of The Royal Mint Limited 08 Management Commentary 18 Sustainability Report 22 Financial Summary 23 Key Ministerial Targets 24 The -

Palestrina in Hastings’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Richard Morrice, ‘Palestrina in Hastings’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XI, 2001, pp. 93–116 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2001 PALESTRINA IN HASTINGS RICHARD MORRICE he development of Hastings as a resort had, by Secretary of State for Ireland ( –) and Home T , been noted in London. Secretary ( –), and rewarded his father with an This fashionable summer retreat bids fair soon to rival earldom in . From to he was Joint Brighton and other hitherto more noted places of Postmaster-General and from to his death in July fashionable resort. The situation, both in point of he held that post on his own. Thomas Pelham scenery and mildness of the air, certainly exceeds any succeeded his father as nd Earl of Chichester in . place of the kind on the southern coast; and what is of He it was who involved Joseph Kay ( – ) in the great consequence to the invalid, the bathing which is scheme, presumably because he had turned to Kay excellent can be accomplished at any time of the tide, without the slightest risk or inconvenience. for works at Stanmer Park, his principal seat, in , the same year that Kay was appointed architect to the Hastings’s reputation was growing, as was its Post Office. population, which doubled in the fifteen years after Hastings was not amongst the very earliest of the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Hastings was above south-eastern seaside resorts, but had certainly all more picturesquely set than other south-eastern followed the lead of Brighton and Margate by the bathing places and, for the Earl of Chichester and his later years of the eighteenth century. -

Coins, Banknotes & Tokens at 11Am Affordable Jewellery & Watches At

Chartered Surveyors Bury St Edmunds Land & Estate Agents 01284 748 625 150 YEARS est. 1869 Auctioneers & Valuers www.lsk.co.uk C Auctioneers & Valuers Tuesday 11th May 2020 Coins, Banknotes & Tokens at 11am Affordable Jewellery & Watches at 2pm Bid online through our website at LSKlive for free – see our website for more details Strong foundation. Exciting future IMPORTANT NOTICES Special attention is drawn to the Terms of Sale on our Bank. LLOYDS, Risbygate Street, BURY ST EDMUNDS website and displayed in the saleroom. CLIENT: Lacy Scott & Knight LLP Paddle Bidding All buyers attending the auction need to ACCOUNT NO: 32257868 register for a paddle number to enable them to bid, this SORT CODE: 30-64-22 process is simple and takes approximately 30 seconds, SWIFT/BIC CODE: LOYDGB21666 however we do require some form of identification i.e. IBAN NO: GB71 LOYD 3064 2232 2578 68 driver's licence. Collection/Delivery All lots must be removed from the Absentee Bidding Buyers can submit commission bids by Auction Centre by midday on the Friday following the email, telephone, or via our website sale unless prior arrangement has been made with the www.lskauctioncentre.co.uk and we will bid on your auctioneers. behalf. It is important to allow sufficient time for Packing and Postage For Jewellery & Watches and Coins commission bids to be processed when leaving bids. Lacy & Banknotes auctions only, we offer a reduced UK Special Scott & Knight offer a free online bidding service via our Delivery charge of £12 per parcel regardless of the website which becomes ‘live’ half an hour before the amount of lots. -

The Gold Metallurgy of Isaac Newton

The Gold Metallurgy of Isaac Newton E. G. V. Newman The Royal Mint, London The science of metals had always appealed to Isaac Newton and when, after the conclusion of his remarkable contributions to mathe- matics and physics, he was invited to take charge of the Royal Mint in London he was able not only to display his great gifts as an administrator but also to exercise his interest in metals and alloys and particularly in the metallurgy of gold. For over thirty years Isaac Newton lived the been accorded him for his scientific work despite the secluded life of a scholar. As undergraduate and later endeavours of his friends Samuel Pepys, John Locke Fellow and Professor at Cambridge he was shy and and Christopher Wren to secure for him a public post reserved, careless of his appearance and even more worthy of his stature. He returned to Cambridge and careless of his eating habits. This period came to a there busied himself with experimental work in triumphant conclusion, of course, with the publication chemistry and metallurgy. of the Principia in 1687. It was not until 1696 that an easement came about For a further period of thirty years, apparently by in the form of an appointment that was to effect a an astonishing transformation, Newton served his complete change in his way of life and his financial country as a highly able public official and also as the welfare. This came through the good offices of an leader of the scientific community. The achievements old friend from his undergraduate days at Trinity and the glory of the former period have not un- College whom he had re-encountered as a fellow naturally overshadowed the latter half of his working Member of Parliament, Charles Montagu. -

Art and Design Coins in the Classroom

Art and Design Coins in the Classroom royalmint.com/kids Fact File 2 Reverse Design Facts Coins with the definitive shield reverse designs entered circulation in 2008. The original decimal designs had been in circulation for almost 40 years and it was felt they needed to be refreshed. The competition to design the coins was a public one and The Royal Mint received more than 4,000 designs from 526 people – the largest ever response to a public competition of this type in Britain. The £1 coin was not originally part of the design brief. A first sift of the drawings was made by three members of The Royal Mint Advisory Committee and 4,000 drawings were reduced to 418 designs. The 418 designs represented 52 series of coins. This was then whittled down to 18 designs representing three series. The designs chosen had to be not just pictures but symbols of the nation. It was decided that the heraldry on some designs was ‘too 2008 Shield Design by Matt Dent Hogwarts’ or ‘Narnia-like’ or it was ‘too gothic and overbearing’. It was said by The Royal Mint Advisory Committee that the winning entry broke ‘the mould in an exciting way’ and ‘is a truly modern series at last.’ Matt Dent The winner of the competition, with the pseudonym Designer Z (as all coin design competitions are anonymous), turned out to be a young graphic designer called Matt Dent, who trained at Coleg Menai in Wales and the University of Brighton. He said about his design that “the piecing together of the elements of the Royal Arms to form one design had a satisfying symbolism – that of unity, four countries of Britain under a single monarch.” Art and Design royalmint.com/kids Fact File 3 UK Coin Design A Penny For Your Thoughts The United Kingdom 1p coin was one of three new coins that joined the 5p, 10p and 50p in general circulation on 15 February 1971 when the United Kingdom adopted a new decimal currency system. -

Royal Mail's Kings and Queen's Series Enters the Tudor

News Release 2 March 2009 ROYAL MAIL’S KINGS AND QUEEN’S SERIES ENTERS THE TUDOR AGE Royal Mail continues its 600 year journey through history with the second in its Kings and Queens series celebrating the Royal Houses of England. Marking the 500th anniversary of the accession of Henry VIII, The House of Tudor, features individual portraits of the six monarchs who ruled during one of the most famous – and infamous - periods in our history, complemented with a four-stamp Miniature Sheet illustrating significant people and events from the period. The stamps - which are issued on 21 April in three 1st, 62p and 81p pairs - and the Miniature Sheet were designed by Atelier Works who also designed the first of the Kings and Queens issues, the Houses of Lancaster and York, in 2008. From the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 to the death of Good Queen Bess in 1603, the age of the House of Tudor saw some of our best known kings and queens sit upon the English throne. Marking the end of the Middle Ages and forged in bloodshed, rancour and upheaval at home and abroad, the Tudor age also saw commerce and arts flourish and the introduction of the Renaissance into England. In addition to its regular products Royal Mail is also producing a Cachet Cover, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I Coin Cover and a Press Sheet consisting of 12 uncut Miniature sheets (see Notes to Editors for further information). Julietta Edgar, Head of Special Stamps at Royal Mail said: “Kings and Queens is one of the most significant series of stamps ever issued by Royal Mail. -

RETIRED STAFF ASSOCIATION (UERSA) NEWSLETTER Issue 38

RETIRED STAFF ASSOCIATION (UERSA) NEWSLETTER Issue 38 January 2017 UERSA website http://groups.exeter.ac.uk/uersa/index.html Change of Editor As members will know, Rachel Kirby has decided to relinquish the editorship of our Newsletter after six years, and we thank her very much for all her work on it. For one year only, I have offered to take her place, while we find another willing volunteer to carry it on. Because of my lack of technical expertise, I have simplified the format and hope members will bear with me! Julie Orr, our Secretary, has kindly agreed to deal with the distribution, taking over from Jan Reynolds – thank you to both, and also to Linda Hale for her continuing help. Sue Odell Chair's New Year Message Dear Friends I've just returned from a very convivial time at UERSA's annual Christmas lunch, held as usual at the Devon Hotel. There was much banter and good humour amongst the 60 of us who sat down for our meal and it's good to know that many of us so enjoy renewing regular contact with former colleagues from all areas of the University – it's very much what UERSA is all about. For those with next year's diaries to hand, you may like to know that Sue Cousins, our Social Secretary, has already booked the date for the 2017 Christmas lunch at the same venue: Thursday 14 December. With the New Year fast approaching, there was some discussion at the recent UERSA Executive Committee meeting about outings for the general membership to supplement those promoted by our Special Interest Groups. -

Sixth Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS

Sixth Session, Commencing at 9.30 am GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS 1687* James I, (1603-1625), third coinage, 1619-25, laurel, fourth head, mm trefoil (S.2638B). Flat in lower left quarter, otherwise very fi ne. $1,500 1684* South Western Britain, uninscribed issue, Durotriges tribal issues, Abstract type, (c58-45 B.C. or earlier), base gold stater, (5.20g), obverse abstracted head of Apollo to right, reverse Celticized disjointed horse to left, circles (legs, pellets and curves) in design (S.365, SCB. 1, Mack 317, Van A. 1235-1 notes as common). Gold with dark regions, good fi ne for issue, rare in this fi neness in gold. $250 Ex Robert Rossini Collection. 1688* Charles I, (1625-1649), unite, Tower Mint, mm rose, issue 1631-1632 (S.2719). Bottom edge repaired at 7 o'clock, otherwise nearly very fi ne. $1,200 1685* South Western Britain, uninscribed issue, Durotriges tribal issues, Geometric type, (c65-58 B.C. or earlier), gold quarter stater, (1.38 g), obverse abstracted pattern with crescent, and appendages hanging from it, reverse geometric pattern with vertical and horiziontal components in the design (S.368 (noted as silver), Van A. 1225-1 notes as common). Very fi ne for issue, rare in this fi neness in gold. $250 1689* Ex Robert Rossini Collection. Anne, after the Union, third bust, guinea, 1711 (S.3574). Attractively toned, nearly extremely fi ne. $2,700 Ex Noble Numismatics Sale 88 (lot 2402). 1690 Anne, third bust, half guinea, 1713 (S.3575). Mount removed, very fi ne/fi ne. $250 1686* Edward III, (1327-1377), Pre Treaty, 1351-61, Noble, series C 1351-2 mm cross 1 (7.56g) (S.1486).