Hebrews 11 - an Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

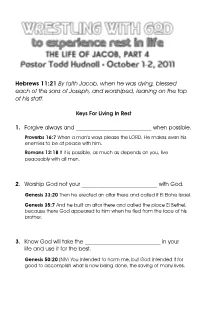

Hebrews 11:21 by Faith Jacob, When He Was Dying, Blessed Each of The

4. Trust that God is your __________________________ even when it doesn’t seem like it. Genesis 48:15 (NIV) “May the God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac walked, the God who has been my shepherd all my life to this day.” Hebrews 11:21 By faith Jacob, when he was dying, blessed 5. Expect God to fulfill His __________________________ without your manipulation. each of the sons of Joseph, and worshiped, leaning on the top of his staff. Genesis 48:14 (NIV) But Israel reached out his right hand and put it on Ephraim’s head, though he was the younger, and crossing his arms, he put his left hand on Manasseh’s head, even though Manasseh was Keys For Living In Rest the firstborn. 1. Forgive always and __________________________ when possible. Proverbs 16:7 When a man’s ways please the LORD, He makes even his enemies to be at peace with him. Group Discussion Questions Romans 12:18 If it is possible, as much as depends on you, live 1. Read Romans 12:18. What is the difference between living peaceably with all men. peaceably and being reconciled? Are there any relationships in your life where you need to establish peace? Are there any relationships in your life where you 2. Worship God not your __________________________ with God. need to reconcile? What do you think you need to do? Genesis 33:20 Then he erected an altar there and called it El Elohe Israel. 2. Why is it important to worship God and not your experience Genesis 35:7 And he built an altar there and called the place El Bethel, with God? Has that ever been a problem for you? Explain. -

The Book of Hebrews

The Book of Hebrews Introduction to Study: Who wrote the Epistle to the Hebrews? A. T. Robertson, in his Greek NT study, quotes Eusebius as saying, “who wrote the Epistle God only 1 knows.” Though there is an impressive list of early Bible students that attributed the epistle to the apostle Paul (i.e., Pantaenus [AD 180], Clement of Alexander [AD 187], Origen [AD 185], The Council of Antioch [AD 264], Jerome [AD 392], and Augustine of Hippo in North Africa), there is equally an impressive list of those who disagree. Tertullian [AD 190] ascribed the epistle of Hebrews to Barnabas. Those who support a Pauline epistle claim that the apostle wrote the book in the Hebrew language for the Hebrews and that Luke translated it into Greek. Still others claim that another author wrote the epistle and Paul translated it into Greek. Lastly, some claim that Paul provided the ideas for the epistle by inspiration and that one of his contemporaries (Luke, Barnabas, Apollos, Silas, Aquila, Mark, or Clement of Rome) actually composed the epistle. The fact of the matter is that we just do not have enough clear textual proof to make a precise unequivocal judgment one way or the other. The following notes will refer to the author as ‘the author of Hebrews,’ whether that be Paul or some other. Is the Book of Hebrews an Inspired Work? Bible skeptics have questioned the authenticity (canonicity) of Hebrews simply because of its unknown author. There are three proofs that should suffice the reader of the inspiration of Hebrews as it takes its rightful place in the NT. -

Hebrews 11-23-31

Hebrews 11-23-31 Prayer for illumination: please join me in prayer…. Sermon introduction: If you live long enough you will face a crisis. Many of you have faced multiple crises in the last year. Some of you have faced a health crisis. Some of you have faced a family crisis. Some of you have lost loved ones. Some of you have faced a work crisis. Some of you have faced a significant relational crisis. Some of you have faced a financial crisis. Some of you have experienced a school crisis. Unfortunately, crises come in all shapes and sizes. How do you respond when a crisis strikes? Some people panic, others plan like crazy, some work harder, others isolate themselves, manipulate others, or medicate with substances, food, or media. None of these responses brings joy and peace! How should we respond? This brings us to the book of Hebrews once again. The recipients of this letter faced a crisis. Hebrews 10:32–34 (ESV) — 32 But recall the former days when, after you were enlightened, you endured a hard struggle with sufferings, 33 sometimes being publicly exposed to reproach and affliction, and sometimes being partners with those so treated. 34 For you had compassion on those in prison, and you joyfully accepted the plundering of your property, since you knew that you yourselves had a better possession and an abiding one. The original audience experienced persecution and affliction simply for being Christians. Some even had their personal property vandalized. They were outcasts. This was a crisis. How should they respond to this crisis? How should you respond to crisis? We find the answer in Hebrews 11:23-31. -

Livingbyfaith-Print.Pdf

Two men stood side by side on a dock one day, peering Otherwise, there’s no way you can navigate through today out into the broad ocean. One looked out and said, “I see a and make it to tomorrow! ship!” The other guy turned his gaze in the same direction and declared, “There’s no ship out there.” “Yes there is,” the first man insisted. “Look,” his friend countered, “I just had an eye exam. I’ve got perfect twenty-twenty vision and I’m telling you, I don’t see a ship.” “Take my word for it. There is a ship.” “How can you be so sure?” the second man asked, squinting hard as he looked out to sea. “I see it clearly through my binoculars.” Your Perspective To a great degree, living a successful Christian life is a No Turning Back matter of perspective. The clarity of your vision can make all the difference and sharp-sightedness often depends on The writer found himself addressing a most perplexing the focusing power of the lens you are using. problem. He was faced with a congregation of people who were contemplating quitting the Christian faith. Even distant images can be brought into crystal clarity with They were considering throwing in the towel because the right optics. In the same way, if we look at our lives they were no longer sure that following the path was through the lens of Scripture, we might discover an ocean worth the pain. They thought that it might just be too liner we failed to notice earlier. -

Better Than the Blood of Abel? Some Remarks on Abel in Hebrews 12:24

Tyndale Bulletin 67.1 (2016) 127-136 BETTER THAN THE BLOOD OF ABEL? SOME REMARKS ON ABEL IN HEBREWS 12:24 Kyu Seop Kim ([email protected]) Summary The sudden mention of Abel in Hebrews 12:24 has elicited a multiplicity of interpretations, but despite its significance, the meaning of ‘Abel’ (τὸν Ἅβελ) has not attracted the careful attention that it deserves. This study argues that τὸν Ἅβελ in Hebrews 12:24 refers to Abel as an example who speaks to us through his right observation of the cult. Accordingly, Hebrews 12:24b means that Christ’s cult is superior to the Jewish ritual. This interpretation fits exactly with the adjacent context contrasting Sinai and Zion symbols. 1. Introduction The sudden mention of Abel in Hebrews 12:24 has elicited a multiplicity of interpretations, but despite its significance, this topic has not attracted the careful attention that it deserves. Traditionally, scholars assert that ‘Abel’ (τὸν Ἅβελ) in Hebrews 12:24 refers to ‘the blood of Abel’.1 Most Bible translators also read ‘than Abel’ (παρὰ τὸν 1 E.g. Ceslas Spicq, L’Épître aux Hébreux, (Paris: Libraire Lecoffee, 1952–53), 2:409-10; Jonathan I. Griffiths, Hebrews and Divine Speech, LNTS (London: T & T Clark, 2014), 143-44; B. F. Westcott, The Epistle to the Hebrews (London: Macmillan, 1892), 417; Harold W. Attridge, Hebrews, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989), 377; James Moffatt, The Epistle to the Hebrews, ICC (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1924); Hugh Montefiore, A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, BNTC (London: A & C Black, 1964), 233; R. -

Of 9 the FAITH of MOSES Hebrews 11:23-28 Key Verses

THE FAITH OF MOSES Hebrews 11:23-28 Key Verses: 11:24,25 "By faith Moses, when he had grown up, refused to be known as the son of Pharaoh's daughter. He chose to be mistreated along with the people of God rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a short time." Moses is known as the most outstanding leader of all leaders who have lived in the world. Moses received the highest education in the palace of the Egyptian Empire for 40 years. For the growth of his inner character, he received another 40 years of humbleness training in the wilderness among seven daughters of Jethro, tending Jethro's flock of sheep. They call this humbleness training or the wilderness seminary. When Moses had completed 80 years of training altogether, God could use him greatly. In the Bible, Moses was known as a servant of God who worked harder than any others to lead his rebellious people; he died without seeing the promised land, though it had been his only dream to see it. There is a saying, "Moses dipped out all the water of a lake, then David caught all the fish and Solomon cooked and ate them all." But the author of Hebrews says that Moses is great because he had faith that pleases God. I. The faith of Moses' parents (23) First, they saw he was no ordinary child (23a). Read verse 23. "By faith Moses parents hid him for three months after he was born, because they saw he was no ordinary child, and they were not afraid of the king's Page 1 of 9 edict." Many great men in history were born in adverse circumstances or in tragic human conditions. -

ELEVEN – Hebrews 11 Sermon Series

ELEVEN – Hebrews 11 sermon series MAKING GOD SMILE Series: Eleven Date: April 7, 2018 Scripture: Hebrews 11 Key sermon points: • The essence of audacious confidence • That’s not faith • Faith is an awareness of the invisible world that produces conviction leading to action • Faith wagers on God’s goodness • Faith prioritizes relationship with God above all • Faith surrenders personal reputation • Faith makes Him smile • A step of faith NOW FAITH IS THE ASSURANCE OF THINGS HOPED FOR, THE CONVICTION OF THINGS NOT SEEN, FOR BY IT THE PEOPLE HAVE ALL RECEIVED THEIR COMMENDATION. BY FAITH WE UNDERSTAND THAT THE UNIVERSE WAS CREATED BY THE WORD OF GOD, SO THAT WHAT IS SEEN WAS NOT MADE OUT OF THINGS THAT ARE VISIBLE BY FAITH. ABEL OFFERED TO GET A MORE ACCEPTABLE SACRIFICE THAN CAIN, THROUGH WHICH HE WAS COMMENDED AS RIGHTEOUS. GOD COMMENDING HIM BY ACCEPTING HIS GIFTS AND THROUGH HIS FAITH, THOUGH HE DIED, HE STILL SPEAKS. BY FAITH ENOCH WAS TAKEN UP SO THAT HE SHOULD NOT SEE DEATH AND HE WAS NOT FOUND BECAUSE GOD HAD TAKEN HIM. NOW BEFORE HE WAS TAKEN, HE WAS COMMENDED AS HAVING PLEASED GOD AND WITHOUT FAITH IT'S IMPOSSIBLE TO PLEASE HIM FOR WHOEVER WHO DRAW NEAR TO GOD MUST BELIEVE THAT HE EXISTS AND THAT HE REWARDS THOSE WHO SEEK HIM. BY FAITH NOAH BEING WARNED BY GOD CONCERNING EVENTS AS YET UNSEEN, IN REVERENT FEAR CONSTRUCTED AN ARK FOR THE SAVING OF HIS HOUSEHOLD AND BY THIS HE CONDEMNED THE WORLD AND BECAME AN HEIR OF THE RIGHTEOUSNESS THAT COMES BY FAITH. -

FROM PATRIARCH to PILGRIM: the Development of the Biblical Figure of Abraham and Its Contribution to the Christian Metaphor of Spiritual Pilgrimage

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Dissertations 1988 From Patriarch to Pilgrim: The evelopmeD nt of the Biblical Figure of Abraham and Its Contribution to the Christian Metaphor of Spiritual Pilgrimage Daniel J. Estes Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Estes, Daniel J., "From Patriarch to Pilgrim: The eD velopment of the Biblical Figure of Abraham and Its Contribution to the Christian Metaphor of Spiritual Pilgrimage" (1988). Faculty Dissertations. 3. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_dissertations/3 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM PATRIARCH TO PILGRIM: The Development of the Biblical Figure of Abraham and its Contribution to the Christian Metaphor of Spiritual Pilgrimage Daniel John Estes Clare Hall A Thesis Submitted to the University of Cambridge for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 - INTRODUCTION 1 1 .1 The Concept of Pilgrimage 1 1.11 Pilgrimage as a Literary Theme 1 1.12 Pilgrimage as a Christian Theme J 1.2 Review of Literature on Abraham 4 1.J Rationale for the Study 10 1.4 Thesis of the Study 12 1.5 Plan for the Study 1) Chapter 2 - ABRAHAM THE SOJOURNER IN GENESIS 12-25 15 2.0 Introduction 15 2,1 Verbs of Movement in the Abrahamic Narratives 15 2.11 Verbs of Geographical Movement 15 2.12 Verbs Related to Tent Dwelling 17 . -

Hebrews 11:8-16 – Sermon Series: Heroes of Faith (Abraham) – June 30Th, 2020

Sermon – Hebrews 11:8-16 – Sermon Series: Heroes of Faith (Abraham) – June 30th, 2020 The Results of Being Heavenly minded Many of you have had the difficult job of sitting at the bedside of someone you loved as they slowly left this world. As difficult as that is, when that person is a Christian, everyone in the room is heavenly minded. The achievements they’ve accomplished in life, their bank account, their job, the good and the bad that a person did in their life is a distant memory. Death has a way of giving us a crystal clear focus on God’s ultimate promise to his people – our heavenly home. But what would happen if a person was that heavenly minded, not only on his death bed but throughout his life? Today we are going to look at Abraham, another hero of faith, who showed that throughout his life he was focused on his heavenly home far more than earthly comforts. So the writer to the Hebrews says something in this lesson that right away is huge example of the faith of Abraham. It says, “By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going” (Heb 11:8). We don’t exactly know what that means. Did God say to Abraham, “head south and I’ll tell you when to stop”? Did he tell him the city he was going to, but Abraham had never heard of the city or anything about it, and in that way he didn’t know where he was going? It got me thinking, because this past week I moved my parents up from Georgia. -

Moses' Decision

Sermon #1063 Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 1 MOSES’ DECISION NO. 1063 A SERMON DELIVERED ON LORD’S-DAY MORNING, JULY 28, 1872, BY C. H. SPURGEON, AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON. “By faith Moses, when he was come to years, refused to be called the son of Pharaoh’s daughter; choosing rather to suffer affliction with the people of God, than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season; esteeming the reproach of Christ greater riches than the treasures in Egypt: for he had respect unto the recompense of the reward.” Hebrews 11:24-26. LAST Sabbath day we spoke upon the faith of Rahab [Sermon #1061, “RAHAB”]. We had then to mention her former unsavory character and to show that, notwithstanding, her faith triumphed, and both saved her and produced good works. Now, it has occurred to me that some persons would say, “This faith is, no doubt, a very suitable thing for Rahab and persons of that class, a people destitute of sweetness and light may follow after the Gospel, and it may be a very proper and useful thing for them, but the better sort of people will never take to it.” I thought it possible that, with a sneer of contempt, some might reject all faith in God, as being unworthy of persons of a higher condition of life and another manner of education. We have, therefore, taken the case of Moses, which stands as a direct contrast to that of Rahab, and we trust it may help to remove the sneer, though, indeed, that may be of small consequence, for if a man or woman is given to sneering it is hardly worth while to waste five minutes in reasoning with him. -

Faith—The Greatest Power in the World (Hebrews 11) Warren Wiersbe

FAITH—THE GREATEST POWER IN THE WORLD (HEBREWS 11) WARREN WIERSBE This chapter introduces the final section of the epistle (Heb. 11—13), which I have called “A Superior Principle—Faith.” The fact that Christ is a superior person (Heb. 1—6) and that He exercises a superior priesthood (Heb. 7—10) ought to encourage us to put our trust in Him. The readers of this epistle were being tempted to go back into Judaism and put their faith in Moses. Their confidence was in the visible things of this world, not the invisible realities of God. Instead of going on to perfection (maturity), they were going “back unto perdition [waste]” (Heb. 6:1; 10:39). In Hebrews 11, all Christians are called to live by faith. In it, the writer discusses two important topics relating to faith. 1. The Description of Faith (11:1–3) This is not a definition of faith but a description of what faith does and how it works. True Bible faith is not blind optimism or a manufactured “hope-so” feeling. Neither is it an intellectual assent to a doctrine. It is certainly not believing in spite of evidence! That would be superstition. True Bible faith is confident obedience to God’s Word in spite of circumstances and consequences. Read that last sentence again and let it soak into your mind and heart. This faith operates quite simply. God speaks and we hear His Word. We trust His Word and act on it no matter what the circumstances are or what the consequences may be. -

1 Hebrews Chapters 10

Hebrews Chapters 10 - 11 If I had to choose a title for our study of this part of the Book of Hebrews today, I would call it The Contrast or The Great Disparity. There is such a difference between the Kingdom of God and that of this world, yet both are in the same place. This is perhaps where much of our greatest struggles lie. We often fail to consider this difference, and how it causes a great pull, a constant drag of the powers of this world; so we try to find the most comfortable spot and we settle somewhere in between. But that is not enough, says Hebrews; there are too many things at stake and why miss out on great blessings? As we are approaching the end of the Book of Hebrews, the author does not spare his words to lay out the contrast. On the one hand, he uses the most encouraging expressions to describe the Kingdom of God, but he uses some very strong eschatological terms and illustrations for the other, so that we see this great gap. For instance, in the section beginning in Hebrews 10:19, where he begins to ask us what we are going to do with all that we have learnt so far, we read of words like confidence, a new and living way; we read of a sincere heart in full assurance of faith, one that is sprinkled clean; we read of pure water and of hope and faith. Then, beginning in Verse 27, it radically changes; there we read of words like a terrifying expectation of judgment, of the fury of fire.