Opera, Narrative, and the Modernist Crisis of Historical Subjectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Complete Catalogue 2006 Catalogue Complete

COMPLETE CATALOGUE 2006 COMPLETE CATALOGUE Inhalt ORFEO A – Z............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Recital............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................82 Anthologie ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................89 Weihnachten ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................96 ORFEO D’OR Bayerische Staatsoper Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................99 Bayreuther Festspiele Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................109 -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

JUNE 2014 LIST See Inside for Valid Dates

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 JUNE 2014 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer, 11th June sees the 150th anniversary of the birth of Richard Strauss and we have already seen a good sprinkling of new releases and re-issues appear in celebration this year. Thielemann’s new Elektra for DG is probably the highest-profile release this month, featuring a magnificent cast that includes Rene Pape and Anne Schwanewilms. Sadly, we hadn’t yet managed to obtain a preview copy at the time of going to print, but it certainly looks very promising! DG are also issuing a deluxe LP-sized boxset of Karajan’s analogue Strauss recordings this month that will feature 11 CDs, plus the entire contents on a single Blu-ray Audio. As is the trend at the moment, it will be a limited edition set packed full of extra material including photos and original liner notes. See p.2 for more information. Continuing with the Strauss theme, you may also like to take a look at the listing we have compiled of recordings from various independent labels. This covers 3½ pages (pp.10-13) and features some truly great titles. A good opportunity to fill in gaps in the library! Away from Strauss, other things to point out are a further batch of Most Wanted Recitals from Decca, featuring wonderful discs from the likes of Siepi, Nilsson, Souzay, Carreras etc. Harmonia Mundi are issuing another 10 titles in their HM Gold series - top recordings moved from their full-price catalogue down to mid-price. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE COMPLETED SYMPHONIC COMPOSITIONS OF ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY DISSERTATION Volume I Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert L. -

Die Seejungfrau Zemlinsky

Zemlinsky Die Seejungfrau NETHERLANDS PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MARC ALBRECHT Cover image: derived from Salted Earth (2017), cling to them. Has Zemlinsky’s time come? photo series by Sophie Gabrielle and Coby Baker Little mermaid in a fin-de-siècle https://www.sophiegabriellephoto.com garment Or is the question now beside the point? http://www.cobybaker.com In that Romantic vein, the Lyric Symphony ‘I have always thought and still believe remains Zemlinsky’s ‘masterpiece’: frequently that he was a great composer. Maybe performed, recorded, and esteemed. His his time will come earlier than we think.’ operas are now staged more often, at least Arnold Schoenberg was far from given to in Germany. In that same 1949 sketch, Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871-1942) exaggerated claims for ‘greatness’, yet he Schoenberg praised Zemlinsky the opera could hardly have been more emphatic in composer extravagantly, saying he knew the case of his friend, brother-in-law, mentor, not one ‘composer after Wagner who could Die Seejungfrau (Antony Beaumont edition 2013) advocate, interpreter, and, of course, fellow satisfy the demands of the theatre with Fantasy in three movements for large orchestra, after a fairy-tale by Andersen composer, Alexander Zemlinsky. Ten years better musical substance than he. His ideas, later, in 1959, another, still more exacting his forms, his sonorities, and every turn of the 1 I. Sehr mäßig bewegt 15. 56 modernist critic, Theodor W. Adorno, wrote music sprang directly from the action, from 2 II. Sehr bewegt, rauschend 17. 06 in surprisingly glowing terms. Zemlinsky the scenery, and from the singers’ voices with 3 III. -

The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years Of

Press release | 30/3/2017 | acr | Updated: July 2017 The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years of the Future of Opera 10 premieres for this major birthday, two of which are reencounters with titles of legendary Felsenstein productions, two are world premieres and four are operatic milestones of the 20 th century. 70 years ago, Walter Felsenstein founded the Komische Oper as a place where musical theatre makers were not content to rest on the laurels of opera’s rich traditions, but continually questioned it in terms of its relevance and sustainability. In our 2017/18 anniversary season, together with their team, our Intendant and Chefregisseur Barrie Kosky and the Managing Director Susanne Moser are putting this aim into practice once again by way of a diverse program – with special highlights to celebrate our 70 th birthday. From Baroque opera to operettas and musicals, the musical milestones of 20 th century operatic works, right through to new premieres of operas for children, with works by Georg Friedrich Handel through to Philip Glass, from Jacques Offenbach to Jerry Bock, from Claude Debussy to Dmitri Shostakovich, staged both by some of the most distinguished directors of our time as well as directorial newcomers. New Productions Our 70 th birthday will be celebrated not just with a huge birthday cake on 3 December, but also with two anniversary productions. Two works which enjoyed great success as legendary Felsenstein productions are returning in new productions. Barrie Kosky is staging Jerry Brock’s musical Fiddler on the Roof , with Max Hopp/Markus John and Dagmar Manzel in the lead roles, and the magician of the theatre, Stefan Herheim, will present Jacques Offenbach’s operetta Barbe- bleue in a new, German and French version. -

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

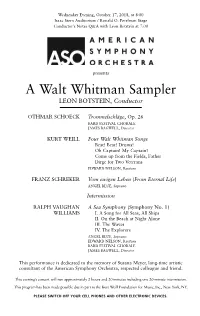

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

DAS WESENTLICHE IST DIE MUSIK Das Ewige Wunderkind Fazil Say, Verliebt in Mozart, Mittlerweile 45 Jahre Alt, Hat Schon Immer Mit Seiner Heimat Gehadert

DAS WESENTLICHE IST DIE MUSIK Das ewige Wunderkind Fazil Say, verliebt in Mozart, mittlerweile 45 Jahre alt, hat schon immer mit seiner Heimat gehadert. Die Türkei ist ihm einfach zu religiös, zu nationalistisch und, unter dem kunstfernen Übervater Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, dem Präsidenten, viel zu autoritär. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 17. Juli 2015 4 PROGRAMM 5 29. MAI 16 Sonntag 16.00 Uhr Abo-Konzert D/6 PHILHARMONIE BERLIN MARKUS POSCHNER FELIX MENDELSSOHN ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY Ferhan & Ferzan Önder / BARTHOLDY (1871 – 1942) Klaviere (1809 –1847) „Die Seejungfrau“ – Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester „Die Hebriden“ – Fantasie in drei Teilen für Berlin Konzertouvertüre h-Moll op. 26 großes Orchester nach dem Märchen von 14.45 Uhr, Südfoyer FAZIL SAY Hans Christian Andersen Einführung von Steffen Georgi (geb. 1970) > Sehr mäßig bewegt „Gezi Park I“ – > Sehr bewegt, rauschend Konzert für zwei Klaviere und > Sehr gedehnt, mit Konzert mit Orchester op. 48 schmerzvollem Ausdruck > Abend und der > Nacht > Polizeirazzia Übertragung heute Abend, 20.03 Uhr. Bundesweit. In Berlin auf 89,6 MHz. PAUSE Das Konzert wird außerdem übernommen von › Schwedischer Rundfunk › Portugiesischer Rundfunk › Tschechischer Rundfunk › Katalanischer Rundfunk › Australian Broadcasting Company 6 7 ROMANTIK VOM ATLANTIK Die Oper und die sinfonische WILDE WINDE UM Dichtung waren Mendelssohns und Brahms’ Sache nicht. Aber EINEN FALSCHEN deswegen ist ihre Musik nicht SÄNGER weniger beredt. Angesichts der mit Händen zu greifenden Natur- Im Frühjahr 1829 dirigierte schilderungen in der so genann- der 20-jährige Mendelssohn in ten absoluten Musik löst sich London (wie vorher in Berlin) der Streit um schildernde oder Bachs Matthäuspassion, spielte um reflektierende Musik in jenen Klavierkonzerte von Weber und Nebel auf, der vor der Inselgrup- Beethoven und stellte im Lande pe der Hebriden genauso aus Shakespeares seine „Sommer- dem Meer aufsteigt wie vor den nachtstraum“-Ouvertüre vor.