Compiled Transcripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lil Baby All of a Sudden Free Mp3 Download ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard

lil baby all of a sudden free mp3 download ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard. ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard zip. “Too Hard” is another 2017 Album by “Lil Baby”. Stream & Download “ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard” “Mp3 Download”. Stream And “Listen to ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard” “fakaza Mp3” 320kbps flexyjams cdq Fakaza download datafilehost torrent download Song Below. 01 Lil Baby – To the Top Mp3 Download 02 Lil Baby – Money Mp3 Download 03 Lil Baby – All of a Sudden (feat. Moneybagg Yo) Mp3 Download 04 Lil Baby – Money Forever (feat. Gunna) Mp3 Download 05 Lil Baby – Best of Me Mp3 Download 06 Lil Baby – Ride My Wave Mp3 Download 07 Lil Baby – Hurry Mp3 Download 08 Lil Baby – Sum More (feat. Lil Yachty) Mp3 Download 09 Lil Baby – Going For It Mp3 Download 10 Lil Baby – Slow Mo Mp3 Download 11 Lil Baby – Trap Star Mp3 Download 12 Lil Baby – Eat Or Starve (feat. Rylo) Mp3 Download 13 Lil Baby – Freestyle Mp3 Download 14 Lil Baby – Vision Clear (feat. Lavish the MDK) Mp3 Download 15 Lil Baby – Dive In Mp3 Download 16 Lil Baby – Stick On Me (feat. Rylo) Mp3 Download. All Of A Sudden. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at $1.49. All Of A Sudden. Copy the following link to share it. You are currently listening to samples. Listen to over 70 million songs with an unlimited streaming plan. Listen to this album and more than 70 million songs with your unlimited streaming plans. -

Now Thats What I Call Love Songs 2013

Now thats what i call love songs 2013 Released three weeks prior to Valentine's Day , Now That's What I Call Love Songs compiles 18 contemporary hits dating back to. Now That's What I Call Love Songs (). TCRYA; 39 . Katy Perry - The One That Got Away (Official) Emeli Sandé - My Kind of Love. Tracklist with lyrics of the album NOW THAT'S WHAT I CALL LOVE SONGS [] from the compilation series Now That's What I Call Music! [] (compilation. This item:Now That's What I Call Love by Various Artists Audio CD £ In stock. Sold by Side . the rest of the year. Includes songs from Rihanna, Katy Perry, Cheryl Cole and Kylie among others. Byklordon 12 June Format: Audio. Jason DeruloSecret Love Song; Miley CyrusThe Climb; Nelly FurtadoI'm Like A Bird; BirdyWings; KeaneSomewhere Only We Know; Lady AntebellumNeed You. Now That's What I Call Love or Now Love is a double-disc compilation album released in the United Kingdom on 30 January Now Love features eleven songs which reached number one on the UK. Now That's What I Call Love features 20 tracks including songs from Colbie Caillat, Maroon 5, . Published on August 14, by Marion the Librarian. Various Artists - Now Love Songs - Music. $ Prime. NOW That's What I Call Love · Now Music . Published on July 17, by Amazon Fan. NOW Thats What I Call Love Songs! is a CD compilation that features some of the hottest pop artists CD Review - Reviewed by Kidzworld on Jan 29, VA – NOW That's What I Call Love Songs () [Deluxe Edition] 39 Love You Like a Love 3 · 40 Bleeding 3 · NOW That's. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Molokai Planning Commission Regular Meeting February 10, 2010

(APPROVED: 04/14/10) MOLOKAI PLANNING COMMISSION REGULAR MEETING FEBRUARY 10, 2010 ** All documents, including written testimony, that was submitted for or at this meeting are filed in the minutes file and are available for public viewing at the Maui County Department of Planning, 250 S. High St., Wailuku, Maui, and at the Planning Commission Office at the Mitchell Pauole Center, Kaunakakai, Molokai. ** A. CALL TO ORDER The regular meeting of the Molokai Planning Commission was called to order by Chairperson Joseph Kalipi at 12:08 p.m., Wednesday, February 10, 2010, at the Mitchell Pauole Center Conference Room, Kaunakakai, Molokai. A quorum of the Commission was present. (See Record of Attendance.) Mr. Joseph Kalipi: If everybody would like to -- welcome everybody to the Molokai Planning Commission. We’ll call this meeting to order. Here with us from the Planning Department: our Program Administrator, Clayton Yoshida. We have Joe Alueta. Back there, Suzie Esmeralda, Clerk. Left of me here is Corporate Counsel, Michael Hopper. Representing the Planning Department, Jane Lovell. To my far right, Commissioner Williams, Commissioner Pescaia, Commissioner Sprinzel, Commissioner Bacon, and Commissioner Vice-Chair Steve Chaikin, and myself, I’ll be Chairing the meeting today, Commissioner Kalipi. B. PUBLIC TESTIMONY ON ANY PLANNING OR LAND USE ISSUE, except Contested Cases as defined in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 91 Mr. Kalipi: So at this time looking at our agenda, we would like to open the floor for any public testimony on any planning or land use issue, except the contested cases as defined in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 91. -

Dossier De Presse

18e édition 19 juin > 12 juillet 2013 04 91 99 02 50 festivaldemarseille.com Contacts Dossier Cécile Robert Isabelle Juanco Attachée relations presse Responsable communication 04 91 99 02 55 04 91 99 02 58 de presse [email protected] [email protected] Calendrier JUIN juiLLET festival de Marseille samedi La comédie musicale égyptienne lundi La Bataille d’Alger danse et arts er multiples 15 Projection 1 Projection 2 Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane mardi Batsheva Dance Company mercredi Dance Company Sadeh21 Play and Play: An Evening 2 Danse 19 of Movement and Music Danse mercredi Batsheva Dance Company Deca Dance Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane 3 Danse jeudi Dance Company Play and Play: An Evening Hubert Colas / 20 of Movement and Music jeudi Sonia Chiambretto Danse 4 GRATTE-CIel Théâtre | CRÉatION samedi Ryoji Ikeda superposition Hubert Colas / 22 Musique / Arts numériques vendredi Sonia Chiambretto GRATTE-CIel mardi 5 Chercheuses d’or Théâtre | CRÉatION 25 Projection Sasha Waltz & Guests Les Chaussons rouges Körper Danse Projection samedi mercredi … … 26 Pierre Droulers 6 Hubert Colas / Soleils Sonia Chiambretto Danse | PREMIÈRE EN FRANCE GRATTE-CIel Théâtre | CRÉatION Flamenco, Flamenco Hubert Colas / Projection dimanche jeudi Sonia Chiambretto … 7 GRATTE-CIel 27 Pierre Droulers Théâtre | CRÉatION Soleils Danse | PREMIÈRE EN FRANCE mardi Georges Appaix / La Liseuse vendredi Univers Light Oblique Orfeu Negro 9 Danse | CRÉatION 28 Projection Georges Appaix / La Liseuse mercredi Que le Spectacle commence Univers Light -

Read an Excerpt

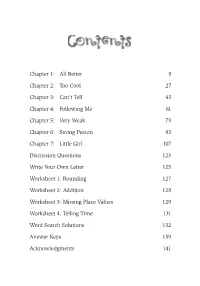

SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 7 Chapter 1: All Better 9 Chapter 2: Too Cool 27 Chapter 3: Can’t Tell 43 Chapter 4: Following Me 61 Chapter 5: Very Weak 79 Chapter 6: Strong Person 93 Chapter 7: Little Girl 107 Discussion Questions 123 Write Your Own Letter 125 Worksheet 1: Rounding 127 Worksheet 2: Addition 128 Worksheet 3: Missing Place Values 129 Worksheet 4: Telling Time 131 Word Search Solutions 132 Answer Keys 139 Acknowledgments 141 SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 9 Chapter 1 “W here are you going? I just know you don’t think you’re going with us, Morgan.” My new cousin Drake, who was my stepdaddy’s nephew, was acting like I had the plague or something. Placing my hands on my hips, I said back with attitude, “Yes, I’m going. That’s why I’m getting my coat. Can you tell Daddy Derek to hold on a second, please?” Since it was December, I also needed to grab my gloves and hat to keep warm. Just as I was heading quickly to my room, I felt somebody behind me stepping on my heel. I knew it was that rude Drake, and he didn’t even say that he was sorry. “No. I won’t tell him that,” Drake said, as he continued to follow me. SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 10 Speak Up! “Ouch!” I yelled out. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents A+Attitude Speak Up Something Special Right Thing No Fear MOODY PUBLISHERS CHICAGO Chapter 1: No Pep 9 Chapter 2: Real Sad 27 Chapter 3: Great News 41 Chapter 4: Low Energy 59 Chapter 5: Bright Spark 77 Chapter 6: Outgoing Kid 95 Chapter 7: Much Charm 111 Discussion Questions 127 Write Your Own Letter 129 Word Keep Book 130 Bonus English Grammar Pages 131 Word Search Solutions 135 Answer Keys 142 Acknowledgments 143 Chapter 1 “Morgan Noelle Love! You have got to get out of the car and let go of my waist, girl. I’m going to be late. You’re squeezing me like I’m a lemon and you’re trying to make lemonade.” My dad said this to me as I hugged him tighter than I used to hold my teddy bear, Goldie, when I was in kindergarten. Now that I was going into the second grade, there was a lot going on. Can’t a kid get a break? I am a big girl now. I don’t need Goldie to make sure I can sleep at night. I’m big enough to know that the bed bugs won’t bite. What I do need is my father, First-Class Captain, Monty Love. He’s leaving me again to go back to the U.S. Navy to serve our country off the coast of Africa. We spent the last two months together, and they were so great. Now our fun time is over. It made me sad to hear him say good-bye, not knowing when he was coming back to Georgia. -

The Power of Simply Answering Questions with Marcus Sheridan

Episode 34: The Power of Simply Answering Questions with Marcus Sheridan E34: THE POWER OF SIMPLY ANSWERING QUESTIONS WITH MARCUS SHERIDAN 00:00 Announcer: Welcome to the Neon Noise podcast. Your home for learning ways to attract more traffic to your websites, generate more leads, convert more leads into customers, and build stronger relationships with your customers. And now your hosts Justin Johnson and Ken Franzen. 00:18 Justin Johnson: Hey, hey, hey, Neon Noise nation. Welcome to the Neon Noise podcast, where we decode marketing and sales topics to help you grow your business. I am Justin and with me, I have my co- host, Ken. Ken, what's going on today? 00:31 Ken Franzen: Not too much, Justin. How are you doing yourself? 00:34 Justin Johnson: I am doing fantastic, thank you. I am extremely excited to talk to our featured guest today. He's got an awesome story, I can't wait to dive in. Today we have on Marcus Sheridan. He is called a web marketing guru by the New York Times. The story of how Marcus was able to save his swimming pool company, River Pools, from the economic crash of 2008 has been featured in multiple books, publications, and stories around the world. And it is also the inspiration for his newest book, "They Ask, You Answer," which is dubbed, "The number one marketing book to read in 2017" by Mashable. Today, Marcus has become a highly sought after global speaker and consultant in the digital sales and marketing space, working with hundreds of businesses and brands alike to become the most trusted voice in their industry while navigating the ultrafast rate of change occurring within consumers and buyers today. -

Télécharger Le Programme De Salle Depuis Votre Smartphone

Emanuel Gat — Bouchra Ouizguen Daina Ashbee — Raimund Hoghe Orlin Robyn Legrand— Catherine / Bagouet Dominique Sharon Sharon Eyal & Gai Behar — Michèle Murray Mourad Merzouki Batsheva Batsheva Dance Company / Ohad Naharin Sylvie Giron & Jean-Charles Di Zazzo Di Jean-Charles Giron & Sylvie í Kylián ř Ballet Ballet de l’Opéra de Lyon / Ji Mathilde Monnier & Olivier Saillard Aina Alegre Kader — & David Attou Wampach Christian Rizzo Anne Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker & Pavel Kolesnikov Nadia Beugré — Arkadi Zaides Karam Natour — Fabrice Ramalingom Ministère de la Culture Une ambition artistique unique Franck Riester Ministre de la Culture Depuis quarante ans, Montpellier crée le mouvement avec une envie et une énergie folle. Elle fait partie des rares métropoles à avoir parié avec raison sur la danse contemporaine dès le début des années 80. Depuis, le succès du Festival Montpellier Danse est allé bien au-delà des espérances puisqu’il est devenu l’un des rendez-vous les plus importants de la danse contemporaine en Europe. Les raisons du succès sont nombreuses mais parmi elles, on peut sans aucun doute évoquer ce savant mélange dans la programmation, où les artistes venus de tous les horizons sont invités, les incontournables de la scène actuelle comme Nadia Beugré, Bouchra Ouizguen ou David Wampach côtoient les légendes Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Ohad Naharin ou encore Jiří Kylián. Ce méticuleux assemblage artistique est un travail de longue haleine réalisé chaque année avec brio par Jean-Paul Montanari et toute son équipe. Je salue chaleureusement cette ambition artistique unique qui ne s’est jamais essoufflée. Le ministère de la Culture s’associe pleinement à cette réussite exemplaire dans l’univers de la danse contemporaine en France où tous les publics sont avides de nouveautés et de surprises, d’enchantement et de grâce. -

2020 Song Index

SEP 26 2020 SONG INDEX 10K (HGA Native Songs, ASCAP/All Essential -B- BLUEBERRY FAYGO (Lil Mosey Publishing CIRCLES (EMI April Music, Inc., ASCAP/Posty DON DON (Los Cangris Publishing, ASCAP/ FREAK (MAU Publishing, Inc., BMI/Prescription Music, ASCAP/Wes The Writer Music, BMI/We Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ Publishing, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publihsing, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt Music Songs, ASCAP/Yeti Yeti Yeti Music, ASCAP/ Are The Good Music Publishing, ASCAP/Atlas BACK HOME (April’s Boy Muzik, BMI/Warner- Callan Wong Publishing Designee, BMI/Franmar WMMW Publishing, ASCAP/Universal Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) LT 10 Cameron Bartolini Music, ASCAP/EPA Publish- Tamerlane Publishing Corp., BMI/Artist Publish- Mountain Songs, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, Music, BMI/Unidisc Music Inc., BMI/Sony/ATV Corp., ASCAP/Nyankingmmusic Inc., ASCAP/ DON’T CHASE THE DEAD (Empire Of Daark- ing, BMI/PW Ballads, BMI/Songs Of Universal, BMI/worshiptogether.com songs, ASCAP/six- ing Group West, ASCAP/My Lord Prophet Music, Songs LLC, BMI/ECAF Music, BMI/Epic/Solar, Quiet As Kept Music Inc., PRS), HL, H100 16 Inc., BMI/Chrysalis Standards, BMI/BMG Plati- ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/Summer ness, BMI/Songs Of Golgotha, BMI/Figs D. steps Music, ASCAP/ThankyouMusic Ltd, PRS/ BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp., BMI/ CITY OF ANGELS (24KGOLDN PUBLISHING, Music, BMI/Concord Publishing, BMI), HL, num Songs US, BMI/Universal Music - Careers, Capitol CMG Genesis, ASCAP), HL, CST 49 Walker Publishing Designee, ASCAP/LVRN Boobie And -

STATE of ILLINOIS 94Th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE

STATE OF ILLINOIS 94th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 20th Legislative Day 2/24/2005 Speaker Turner: “The House shall be in order. We shall be led in prayer today by Lee Crawford, the Assistant Pastor of the Victory Temple Church in Springfield. Members and their guests are asked to refrain from starting their laptops, turn off all cell phones and pagers and rise for the invocation and for the Pledge of Allegiance. Lee Crawford.” Pastor Crawford: “Let us pray. Most gracious God, who art in heaven, Father, we invoke Your glory into this house. We’re thankful to be able to come before Your holy presence and to declare that Your name alone is holy and undefiled. We ask that this day that Your kingdom would come, that Your will will be done on this earth as it is in heaven. We ask that You would give us this day our daily bread and the things that we have need of, for we are in need of wisdom, understanding, strength, both physical and spiritual. Father, I ask that You would forgive us all of our debts, as we forgive all of our debtors. Lead us not into temptation, but we ask that You would deliver us from all evil. For Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory this day and forever more. Amen.” Speaker Turner: “We shall be led in the Pledge today by the Gentleman from Tazewell, Representative Sommer.” Sommer – et al: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” 09400020.doc 1 STATE OF ILLINOIS 94th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 20th Legislative Day 2/24/2005 Speaker Turner: “Roll Call for Attendance. -

A Promise of Tomorrow: the Effects of UNHCR and UNICEF Cash Assistance on Syrian Refugees in Jordan 3 Contents

Report A promise of tomorrow The effects of UNHCR and UNICEF cash assistance on Syrian refugees in Jordan Bassam Abu Hamad, Nicola Jones, Fiona Samuels, Ingrid Gercama, Elizabeth Presler-Marshall and Georgia Plank With Aida Essaid, Said Ebbini, Kifah Bani Odeh, Deya’eddin Bazadough, Hala Abu Taleb, Hadeel Al Amayreh and Jude Sadji November 2017 UNICEF promotes the rights and wellbeing of every child, in everything we do. Together with our partners, we work in 190 countries and territories to translate that commitment into practical action, focusing special effort on reaching the most vulnerable and excluded children, to the benefit of all children, everywhere. UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, is a global organisation dedicated to saving lives, protecting rights and building a better future for refugees, forcibly displaced communities and stateless people. UNHCR leads international action to protect people forced to flee their homes because of conflict and persecution. We deliver life-saving assistance like shelter, food and water, help safeguard fundamental human rights, and develop solutions that ensure people have a safe place to call home where they can build a better future. We also work to ensure that stateless people are granted a nationality. Our dedicated staff work in 130 countries around the world, from major capitals to remote and often dangerous locations. UNICEF and UNHCR are grateful to the following donors for their generous contributions that has made this critical financial assistance to the most vulnerable refugee families and their children possible: Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax.