TRIALOG 104 a Journal for Planning and Building in the Third World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa

Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa Essays and speeches by Neville Alexander (1985–1989) Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa was first published by Skotaville Publishers. ISBN 0 947479 15 5 © Copyright Neville Alexander 1990 All rights reserved. This digital edition published 2013 © Copyright The Estate of Neville Edward Alexander 2013 This edition is not for sale and is available for non-commercial use only. All enquiries relating to commercial use, distribution or storage should be addressed to the publisher: The Estate of Neville Edward Alexander, PO Box 1384, Sea Point 8060, South Africa Contents Preface 3 What is happening in our schools and what can we do about it? 4 Ten years of educational crisis: The resonance of 1976 28 Liberation pedagogy in the South African context 52 Education, culture and the national question 71 The academic boycott: Issues and implications 88 The tactics of education for liberation 102 Education strategies for a new South Africa 115 The future of literacy in South Africa: Scenarios or slogans? 142 Careers in an apartheid society 152 Restoring the status of teachers in the community 164 Bursaries in South Africa: Factors to consider in drafting a five-year plan 176 A democratic language policy for a post-apartheid South Africa/Azania 188 African culture in the context of Namibia: Cultural development or assimilation? 205 PREFACE THE FOLLOWING ESSAYS AND SPEECHES have been selected from among numerous attempts to address the relationship between education and the national liberation struggle. All of them were written or delivered in the period 1985–1989, which has been one of the most turbulent periods in our recent history, more especially in the educational arena. -

School Leadership Under Apartheid South Africa As Portrayed in the Apartheid Archive Projectand Interpreted Through Freirean Education

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION Kevin Bruce Deitle University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Deitle, Kevin Bruce, "SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11696. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11696 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECT AND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION By KEVIN BRUCE DEITLE Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Educational Leadership The University of Montana Missoula, Montana March 2021 Approved by: Dr. Ashby Kinch, Dean of the Graduate School -

Section 5 Voices of the People: Case Studies of Medium-Density Housing

SECTION 5 VOICES OF THE PEOPLE: CASE STUDIES OF MEDIUM-DENSITY HOUSING SECTION 5: VOICES OF THE PEOPLE - CASE STUDIES OF MEDIUM-DENSITY HOUSING 189 VOICES OF THE PEOPLE: CASE STUDIES OF MEDIUM-DENSITY HOUSING 1. Overview Table 38: Overview of case studies Date of interviews Project Location Tenure with residents Spring Þeld Terrace Cape Town (South Africa) Sectional title (rental February 2005 and ownership) Carr Gardens Johannesburg (South Africa) Social rental April 2005 Newtown Housing Cooperative Johannesburg (South Africa) Cooperative housing February 2005 Stock Road Cape Town (South Africa) Installment sale March 2005 (eventual individual ownership) Missionvale Nelson Mandela Metro Individual ownership November 2004 (South Africa) Samora Machel Cape Town (South Africa) Individual ownership November 2004 Sakhasonke Village Nelson Mandela Metro Individual ownership March 2007 (South Africa) N2 Gateway – Joe Slovo (Phase1) Cape Town (South Africa) Social rental January 2008 Washington Heights Mutual New York (USA) Rental Housing Association Vashi Navi Mumbai (India) Cooperative housing Vitas Housing Project Manila, Tondo (Philippines) Rental and ownership The majority of South Africans were denied ensure a more equitable resource distribution. 1 human rights and essential livelihood resources for hundreds of years, especially under apartheid. In this regard, the case studies discussed look Since 1994 the country’s Þrst democratically at the extent and implications of community elected government has approved numerous laws participation in the development and imple- and policies, established development programmes, mentation processes of higher-density housing and rati Þed international treaties to ensure the projects. They explore prospects of approaching realisation of basic human rights, as de Þned in the the future delivery of higher-density housing in a South African Constitution. -

South Africa Tackles Global Apartheid: Is the Reform Strategy Working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, Pp.819-841

critical essays on South African sub-imperialism regional dominance and global deputy-sheriff duty in the run-up to the March 2013 BRICS summit by Patrick Bond Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africas Development – in Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnstone (Eds), Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, London, Pluto Press, 2005, pp.230-236. US empire and South African subimperialism - in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys (Eds), Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded, London, Merlin Press, 2004, pp.125- 144. Talk left, walk right: Rhetoric and reality in the New South Africa – Global Dialogue, 2004, 6, 4, pp.127-140. Bankrupt Africa: Imperialism, subimperialism and financial politics - Historical Materialism, 12, 4, 2004, pp.145-172. The ANCs “left turn” and South African subimperialism: Ideology, geopolitics and capital accumulation - Review of African Political Economy, 102, September 2004, pp.595-611. South Africa tackles Global Apartheid: Is the reform strategy working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, pp.819-841. Removing Neocolonialisms APRM Mask: A critique of the African Peer Review Mechanism – Review of African Political Economy, 36, 122, December 2009, pp. 595-603. South African imperial supremacy - Le Monde Diplomatique, Paris, May 2010. South Africas dangerously unsafe financial intercourse - Counterpunch, 24 April 2012. Financialization, corporate power and South African subimperialism - in Ronald W. Cox, ed., Corporate Power in American Foreign Policy, London, Routledge Press, 2012, pp.114-132. Which Africans will Obama whack next? – forthcoming in Monthly Review, January 2012. 2 Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Introduction Distorted forms of capital accumulation and class formation associated with neoliberalism continue to amplify Africa’s crisis of combined and uneven development. -

New Labour Formations Organising Outside of Trade Unions, CWAO And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE Research Report for the degree of Master of Arts in Industrial Sociology, submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Nkosinathi Godfrey Zuma Supervisor: Prof. Bridget C. Kenny Title: ‘Contingent organisation’ on the East Rand: New labour formations organising outside of trade unions, CWAO and the workers’ Solidarity Committee. Wits, Johannesburg, 2015 1 COPYRIGHT NOTICE The copyright of this research report rests with the University of the Witwaterand, Johannesburg, which it was submitted, in accordance with the University’s Intellectual Property Rights Procedures. No portion of this report may be produced or published without prior written authorization from the aurthor or the University. Extract of or qoutations from this research report may be included provided full acknowledgement of the aurthor and the University and in line with the University’s Intellectual Property Procedures. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost appreciation goes to my supervisor Prof. Bridget Kenny for her endless intellectual guiedance and encouragement throughout this research report. It has been a great incalculable experience learning and be montored by Prof. Kenny. Without your support the complition of this report would be more difficult. I highly appreciate the warm welcome and support given to me by the Advice office (CWAO) in Germiston. My special thanks go to Ighsaan Schroeder for your support and permitting me access to your office. Thank you for the interviews you afforded me. Secondly, my special thanks go to Thabang Mohlala for your support and willingness to help me organise the interviews. -

Khanya – Trade Unions and Struggles for Democracy

UFIL' UMUNTU, UFlC USADIKIZA! Trade Unions and Struggles for Democracy and Freedom in South Africa, 1973 - 2003 The title of this booklet, "Ufil' Umuntu, Ufil'Usadikiza!" (The person is dead but hislher spirit is alive!), is a slogan which was chanted by the workers during the Durban strikes of 1973 . - --- KHANYA ?CCOLLz EDUCATITION FO~ILIBERATION Published by KHANYA College 0Khanya College 2005 This book is meant for educational puposes. Any individuals or organisations that wish to make use of the contents in the book for educational puposes that are not for profit are free to do so. We only request that you acknowledge our work. Page Number ISBN 0-620-33970-5 Design 0jon berndt DESIGN INTRODUCTION All photographs copyright resides with the acknowledged photographers or photographic archive. THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOKLET Black and White Photograph on front cover: William Matlala LIST OF ACRONYMS CHAPTER ONE: The working class on the eve of the Durban strikes CHAPTER TWO: Durban strikes and the reawakening of the working class CHAPTER THREE The birth of a new trade union movement CHAPTER FOUR Apartheid capitalism and the crisis of the 1980s CHAPTER FIVE The response of the capitalists, the state and working class CHAPTER SIX From apartheid capitalism to non-racial capitalism CHAPTER SEVEN The end of the cycle of struggle It has been such a long road by Alfred Temba Qabula Recommended Sources for further information r The 1973 strikes in Durban and the subsequent wave of worker uprisings are regarded as t This booklet has been researched by the staff of the Khanya Working Class History I important landmarks in the making of the South African labour movement. -

Market-Assisted Agrarian Reform in South Africa

1 An Examination of Market-assisted Agrarian Reform in South Africa Commissioned by the International Union of Foodworkers (IUF) Researched by Susan Tilley for the International Labour Resource and Information Group (ILRIG) Contents Map of South Africa showing the various provinces and ex-homeland areas Page: Executive Summary i - iv 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………1 2. What is meant by Market-Assisted Agrarian Reform?……………3 3. A history of land tenure and agriculture in South Africa…………5 4. The framework for agrarian Reform…………………………………..9 5. Land reform strategies………………………………………………….16 6. Monitoring and evaluation of land reform…………………………..36 7. Conclusions - land reform and social transformation ……………37 8. Discussion questions and related index ……...……………………42 9. Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………..42 10. Appendices ……………………………………………………..……….43 11. End notes ………………………………………………………..………52 _________________________________________________________________ An Examination of Market-assisted Agrarian Reform in South Africa An Examination of Market-assisted Agrarian Reform in South Africa 1. Introduction The attainment of a hard-won improvements. Approximately 14 million democracy in South Africa after the people, or about one third of the South 1994 general elections was African population, still live in the former accompanied by high expectations of Bantustans1 where rights to land remain the ANC-led government to transform unclear or are contested. The system of property rights dramatically and to communal land administration is in a reverse the history of land state of disarray. On private farms, dispossession. The expectation was that millions of farm dwellers and their this would establish the basis for an families confront tenure insecurity and improvement in the lives of the poor and lack access to basic necessities such as dispossessed. -

Educational Barriers for Zimbabweans in South Africa

THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN MIGRATION PROGRAMME RIGHT TO THE CLASSROOM: EDUCATIONAL BARRIERS FOR ZIMBABWEANS IN SOUTH AFRICA MIGRATION POLICY SERIES NO. 56 RIGHT TO THE CLASSROOM: EDUCATIONAL BARRIERS FOR ZIMBABWEANS IN SOUTH AFRICA JONATHAN CRUSH AND GODFREY TAWODZERA SERIES EDITOR: PROF. JONATHAN CRUSH SOUTHERN AFRICAN MIGRATION PROGRAMME (SAMP) OPEN SOCIETY INITIATIVE FOR SOUTHERN AFRICA (OSISA) 2011 Published by Idasa, 6 Spin Street, Church Square, Cape Town, 8001, and Southern African Research Centre, Queen's University, Canada. Copyright Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP) 2011 ISBN 978-1-920409-68-5 First published 2011 Design by Bronwen Müller References and further reading may be available for this article. To view references and further reading you must purchase this article. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Bound and printed by Logo Print, Cape Town CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 3 THE RIGHT TO THE CLASSROOM 4 BARRIERS TO ADMISSION 9 STUDY METHODOLOGY 11 ACCESSING THE RIGHT TO EDUCATION 12 FINANCIAL BARRIERS 14 DISCRIMINATION AND XENOPHOBIA 16 LANGUAGE PROBLEMS 17 OBSTACLES IN THE TERTIARY SECTOR 18 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 21 ENDNOTES 24 MIGRATION POLICY SERIES 27 TABLE 1: REFUGEE APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS, 2009 10 MMIGRATIONIGRATION PPOLICYOLICY SERIESERIES NO. 4556 EXEXECUTIVECUTIVE SSUMMAUMMARYRY hisealth report workers examines are onethe obstaclesof the categories to access of by skilled Zimbabwean profession- childrenals most and affected students by globalization.to schools and Over tertiary the institutions past decade, in Souththere Africa. has emerged There ais substantiala common bodyassumption of research in South that Africatracks thatpatterns these ofchildren international and students migration have of no health right topersonnel, an educa- THtion in South Africa. -

Proposed Role in the Project

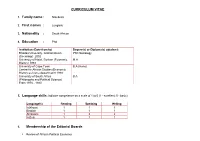

CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Family name : Ntsebeza 2. First names : Lungisile 3. Nationality : South African 4. Education : Phd Institution (Date from/to) Degree(s) or Diploma(s) obtained: Rhodes University, Grahamstown PhD Sociology (Sociology) 2002 University of Natal, Durban (Economic M.A History) 1993 University of Cape Town B.A (Hons) Centre for African Studies (Economic History as home department) 1988 University of South Africa B.A (Philosophy and Political Science) From 1978 - 1980 5. Language skills: Indicate competence on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 - excellent; 5 - basic) Language(s) Reading Speaking Writing IsiXhosa 1 1 1 English 1 1 1 Afrikaans 1 3 2 IsiZulu 1 1 1 6. Membership of the Editorial Boards . Review of African Political Economy . Journal of Contemporary African Studies . Social Dynamics, University of Cape Town . South African Review of Sociology . Agrarian South . Socialist History, Manchester, UK . International Political Science Review . South Africa-Vrije Universiteit Strategic Alliance (SAVUSA), Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands which publishes books in the African Studies series of Brill Academic Publishers in Leiden . South African Democracy Education Trust, Pretoria 7. Membership of Professional Bodies and Research Initiatives . CODESRIA . South African Association for Canadian Studies . South African Sociological Association 8. Other skills Fully computer literate, Microsoft Office user Workshop Facilitation and Programme evaluation. 9. Present position Full Professor and Acting Director, Centre for African -

Building Workers' Education in the Context of the Struggle Against

Building Workers’ Education in the Context of the Struggle Against Racial Capitalism: The Role of Labour Support Organisations Mondli Hlatshwayo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6533-8585 University of Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] Abstract In South Africa, with few exceptions, scholarship on the modern labour movement which emerged after the Durban strikes of 1973 tends to focus on trade unions that constituted the labour movement, strikes, collective bargaining, and workplace changes. While all these topics covered by labour scholars are of great importance, there is less emphasis on the role played by labour support organisations (LSOs) which, in some cases, predate the formation of the major trade unions. Based on an analysis of historical writings, some archival and internet sources, this article critically discusses the contribution of LSOs and their use of workers’ education to build and strengthen trade unions, which became one of the critical forces in the struggles against racial capitalism in the 1980s. In particular, it critically examines the work of the Urban Training Project (UTP) and the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) workers’ education programmes as a contribution to building the labour movement. The relationship between trade unions which had elaborated structures of accountability and LSOs which were staffed by a relatively small layer of activists also led to debates about accountability and mandates. Keywords: workers’ education; trade unions; labour support organisations; non-governmental organisations Introduction Labour studies literature has tended to focus on trade unions as institutions of workers that had a national presence and were able to develop organisational infrastructure, with the main purpose being struggle for social and economic justice in the context of racial capitalism (Buhlungu 2010; Forrest 2011; Friedman 1987; von Holdt 2003; Webster 1985). -

Khanya Home Jbf Home About Jbf Press & Media

Jozibook fair 2010 http://jozibookfair.org.za/2FhighJB28/exhibitors.htm KHANYA HOME JBF HOME ABOUT JBF PRESS & MEDIA 1 of 24 06/03/2017 21:58 Jozibook fair 2010 http://jozibookfair.org.za/2FhighJB28/exhibitors.htm JBF NEWSLETTER PHOTO GALLERY READING CIRCLES CULTURE OF READING CAMPAIGN EXHIBITORS AUTHORS & SPEAKERS PROGRAMME 2010 JBF 2009 SPONSORS LINKS & PARTNERS CONTACT US Vacancies Vacancies Available at Khanya College See you there! Newsletter 2 of 24 06/03/2017 21:58 Jozibook fair 2010 http://jozibookfair.org.za/2FhighJB28/exhibitors.htm Jozi Book Fair My Class Newsletter, Current Issue Were you there? See you there! Jozi Book Fair welcomes the publishers, book sellers, publisher-writers (self-publishers), and NGOs who will be exhibiting at the fair. The following exhibitors are registered for stalls at the fair, which will be held at Museum Africa in Newtown. Click here for the floor space plan 3rd Floor and 4th Floor. Afrikan African amaBooks AIDC Wrights us Perspective ALLABOUTWRITING Publishers Forum Publishing Dream Team Abantwana Brahma Kumaris World MAPPP-SETA Kudjon Consulting Trading Marketing Spiritual University Amnesty International South ANFASA Bookdealers Botsotso Publishing Chall Support Africa David Krut Dinkwe Chimurenga Ebukhosini Solutions French Institute Publishing Production 3 of 24 06/03/2017 21:58 Jozibook fair 2010 http://jozibookfair.org.za/2FhighJB28/exhibitors.htm Flamenco Graysonian Grail Message Genderlinks Goethe Institute Publishing Press Foundation Hibbard Publishers Knowledge Thirst Isipho Books Ilrig -

Annual Report 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011

Annual Report 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Khanya College 5th Floor House of Movements 123 Pritchard Street Johannesburg 2001 Tel: 011 336 9190 Fax: 011 336 9196 Postal Address P. O. BOX 5977 Johannesburg 2000 South Africa www.khanyacollege.org.za [email protected] CONTENTS 1. Message from the College Coordinator 1 2. About Khanya College 3 3.1 The programmes of Khanya College 5 3. Organisational and Programmatic Structure of Khanya College 5 4. The Context, Achievements and Priorities: From CRISIS to RESISTANCE 9 4.1 The Context 9 4.2 Overall Achievements in 2011 13 4.3 Strategic Objectives for 2012-2014 14 4.4 Priorities for 2012 15 5. Khanya College Evaluation 2011 16 5.1 Brief Overview: Khanya College External Evaluation Report 2011 16 5.2 Excerpts from the Khanya College External Evaluation Report 2011 16 6. Key interventions and activities in 2011 18 6.1 Setsi sa Mosadi women’s centre 18 6.2 Khanya College Annual Winter School 20 6.3 Jozi Book Fair 25 6.4 Strategy Centre for Social Movements 27 6.5 Khanya Working Class History Programme 30 6.6 ICT and Movement building 32 7. Institutional Developments 34 7.1 The Board of Trustees of Khanya College 34 7.2 Staffing and Coordination 34 7.3 Institutional Consolidation and Strengthening 36 7.4 The Funding Outlook 2012-14 37 8. Towards the ALL COLLEGE CONFERENCE 2012 38 The context to the All College Conference 2012 38 The All College Conference: composition, agenda and process 40 9. Appendices 41 9.1 Board of Trustees of Khanya College 41 9.2 Khanya Staff 42 9.3 Khanya Activities 2011 43 9.4 Khanya Publications 2011 43 9.5 South African Farmworkers Network 44 9.6 NGO Referral Network 44 9.7 Khanya College Donors 45 9.8 Organisations Khanya worked with in 2011 45 1.