Societal Impacts Societal Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAH 1 2 Contents 1..2

VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 NOVEMBER 2018 ISSN 2515 - 0456 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 27 Sep 2021 at 09:51:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use. Modern American History (MAH) showcases top-quality, emerging research on the history of the United States since the 1890s. Aiming to stimulate debate and make meaningful connections between the subfi elds of this vibrant and expansive fi eld, the journal publishes compelling peer-reviewed articles as well as substantial review essays, forums, and other special features. Executive Editors Brooke L. Blower, Boston University, MA Sarah T. Phillips, Boston University, MA Editorial Assistants Cari Babitzke, Boston University, MA Andrew Bell, Boston University, MA Editorial Board Thomas G. Andrews, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO Beth Bailey, University of Kansas, KS Brian Balogh, Miller Center, University of Virginia, VA Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Harvard Law School, MA Geraldo Cadava, Northwestern University, IL Margot Canaday, Princeton University, NJ Christopher Capozzola, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA Jefferson Cowie, Vanderbilt University, TN Beverly Gage, Yale University, CT Gary Gerstle, University of Cambridge, UK Jacob Darwin Hamblin, Oregon State University, OR Madeline Y. Hsu, University of Texas, Austin, TX Sarah E. Igo, Vanderbilt University, TN Robin D. G. Kelley, University of California, Los Angeles, CA Barbara Keys, University of Melbourne, Australia Kevin M. Kruse, Princeton University, NJ Adriane Lentz-Smith, Duke University, NC Melani McAlister, George Washington University, DC Andrew Preston, University of Cambridge, UK Samuel K. Roberts, Columbia University, NY Bruce J. Schulman, Boston University, MA Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson, Universität Augsburg, Germany Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, University of California, Irvine, CA Cover image: Flip Schulke photographs residents taking part in organized daily pool exercises at the Century Village Retirement Community in West Palm Beach, Florida, c. -

All FOIA Requests Received in October 2017

All Requests Received October 1 - 31, 2017 Tracking Number Requester Name Organization Received Date Description Good Afternoon — I am with ProPublica Illinois, a statewide newsroom based in Chicago. I am seeking all documents and records that the EPA and EPA Region 7 has associated with Woolsey Operating Company (and affiliate names), including its high- volume hydraulic fracturing operations and permitting (Illinois Department of Natural Resources Registration #: HVHHF-00003). The Kansas names and addresses for Woolsey are as follows: WOOLSEY PETROLEUM LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1983 105 N MARKET ST STE 600, WICHITA, KS 67202-1801 (Agent: BRUCE C. WARD at STE 400 300 W DOUGLAS, WICHITA, KS 67202 WOOLSEY PETROLEUM CORPORATION 125 N MARKET STE 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202-1807 (Agent: KAY WOOLSEY at 107 N MARKET / STE 600, WICHITA, KS 67202) WOOLSEY OPERATING COMPANY, LLC 125 N MARKET SUITE 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202 (Agent: KAY WOOLSEY at 125 NORTH MARKET SUITE 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202) WOOLSEY INVESTMENTS, LLC 125 N Market Suite 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202 (Agent: I. WAYNE WOOLSEY at 125 N Market Suite 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202) WOOLSEY FIVE, LLC 125 N Market Suite 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202 (Agent: KAY WOOLSEY at 125 N Market Suite 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202) WOOLSEY ENERGY II, LLC 125 N Market Suite 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202 (Agent: I. WAYNE WOOLSEY at 125 N Market Suite 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202) WOOLSEY ENERGY CORPORATION 125 N MARKET STE 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202 (Agent: I. WAYNE WOOLSEY at 125 N MARKET STE 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202) WOOLSEY COMPANIES, INC. 125 N. MARKET ST. STE 1000, WICHITA, KS 67202 (Agent: J. -

Engineering the Environment: Regulatory Engineering at the U.S

Engineering the Environment: Regulatory Engineering at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1970-1980 Jongmin Lee Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Science and Technology Studies Matthew H. Wisnioski, Chair Mark V. Barrow, Jr. Gary L. Downey Saul Halfon Ann Johnson August 2, 2013 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: air pollution, control technology, environmental regulation, regulatory engineering, catalytic converter, scrubber, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Copyright Jongmin Lee Engineering the Environment: Regulatory Engineering at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1970-1980 Jongmin Lee ABSTRACT My dissertation addresses how engineers, scientists, and bureaucrats generated knowledge about pollution, crafted an institution for environmental protection, and constructed a collective identity for themselves. I show an important shift in regulators’ priorities, from stringent health-based standards to flexible technology-based ones through the development of end-of-pipeline pollution control devices, which contributed to the emergence of economic incentives and voluntary management programs. Drawing on findings from archival documents, published sources, and oral history interviews, I examine the first decade of the EPA amid constant organizational changes that shaped the technological and managerial character of environmental policy in the United States. Exploring the EPA’s internal research and development processes and their relationship with scientific and engineering communities sheds light on how the new fields of environmental engineering and policy were co-produced in the 1970s. I argue that two competing approaches for environmental management, a community health approach and a control technology approach, developed from EPA’s responses to bureaucratic, geographical, and epistemic challenges. -

State Caucus Representative Reports

Delaware Caucus Report Steering Committee Meeting April 25, 2013 Erie, PA Winterthur Library Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library is pleased to announce that it has acquired the John and Carolyn Grossman Collection, an assemblage of 250,000 items that documents chromolithography and all it represented visually from approximately 1820 to 1920. The collection portrays the customs, attitudes, and ideals of Victorian and Edwardian life and is one of the most comprehensive archives of period graphic ephemera ever to have been assembled. The finest examples are represented, including calendars, greeting cards, trade cards, product labels, paper dolls, tickets, postcards, scrapbooks, sheet music, etc. Among the treasures of the collection are the first commercially produced Christmas card (England, 1843), its accompanying printer’s proof, and an early American Christmas card from around 1850. As well, the Grossmans saved the archive of the George Schlegel Lithographic Company, a 19th and 20th century New York City business that specialized in cigar box label printing. Having the Grossman Collection at Winterthur solidifies the library’s status as a center for advanced research in the visual arts. Lewes Historical Society The Lewes Historical Society has recently acquired the papers of Citizens' Coalition, Inc., a non-profit organization that reviewed and kept track of land use decisions in Sussex County, Del., from the late 1990s through last year when it dissolved. As land use and development are critical issues in southern Delaware at the turn of the 21st century, this collection will yield insight into local sentiment and politics regarding decision making and changing demographics in the region. -

The Bittersweet Waters of the Lower Colorado by ROWE FINDLEY SENIOR EDITORIAL STAFF Photographs by CHARLES O'rear

The Bittersweet Waters of the Lower Colorado By ROWE FINDLEY SENIOR EDITORIAL STAFF Photographs by CHARLES O'REAR RYSTAL DROPS OF SNOWMELT give the river birth, high in the Rockies of its namesake state . Nourished by C tributaries from Wyoming's Wind River Range and Utah's Uintas, it grows to mus- cular youth . In vigorous midcourse it cuts mighty canyons through desert plateaus in its rush toward the sea. Then, along its final 400 miles or so toward the Gulf of California, the Colorado becomes a different river . Once those final miles were the most ripsnortin' of all . Here the full-grown river broadened out in wide valleys, looped in great bends, and stampeded over everything in its path during unpredictable floods . Then, beginning with Hoover Dam in 1935, man began to harness that brute power ; today a series of dams holds back the lower river and turns it out to water towns and industries and millions of desert acres (map, page 546). Now, in its last 70 miles, the feeble river is reduced to a trickle, in size comparable Sluicing through wind-driven dunes, the All American Canal carries the tamed and dutiful waters of the lower Colorado westward toward California's Imperial Valley. Prodigious thirsts of farms, cities, and industries virtually dry up the mighty river before it finds the sea . THIS SURVEY INCLUDES A NUMBER OF PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY MR . O'REAR FOR THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY'S 'PROJECT DOCUMERICA' 540 to its infancy, and in quality merely brack- ncll 14) protcrI i1, illollrll •I l .lr( In 1'u0 the ish drainage from salt-plagued irrigation ruurt rulcll .\l iiun;l." won projects . -

The History of the American Environmental Policy Reflects How

Troubled Waters: The Confluence of Local, State and Federal Environmental Policy at the Headwaters of the Dolores River, from the Height of the Cold War to 2004 By Rebecca Levy Major: U.S. History Fort Lewis College Mentor: Michael Fry, PhD ABSTRACT Guaranteeing a sufficient supply of clean water is one of the biggest environmental problems facing the United States. This problem is dramatically exacerbated in the arid Southwest, where the limited water resources are shrinking, as demand for clean water is increasing. Compounding the problem is the environmental contamination from historic mining activities. Often located near headwaters, abandoned hard rock mines and mine waste piles deposit heavy metals into the streams and rivers of many of the western watersheds. Pollution from historic mining activities further degrades the quality of this limited resource, making the protection of clean water essential to the viability of life in the west. The town of Rico, Colorado is situated at the headwaters of the Dolores River, a tributary to the Colorado, and is surrounded by abandoned silver, lead, zinc, gold and copper mines. Rico‟s mines have been contaminating the Dolores River for over a century. Despite its isolated location, the environmental history of the Rico region illustrates how actions undertaken locally are determined by state and federal policy decisions. These policy decisions are often influenced by national public sentiment and economic trends, rather than empirical science, remedial objectives or local needs. This study is part of a growing body of environmental history that focuses on the evolution of environmental policy. By incorporating previously unused official accounts from town records, including board minutes and letters, this study contributes to future research on the history of Rico, and on environmental history in general. -

Sustainability: Designing Interdisciplinary Opportunities for Teaching

Sustainability: Designing Interdisciplinary Opportunities for Teaching Lori De La Cruz SMU Graduate Student Sustainability & Development – Lyle School of Engineering Mountain View College Sustainability Coordinator This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Cover Photo Credit: Jacob Ammentorp Lund/iStock/Thinkstock About this Workbook The Sustainability: Designing Interdisciplinary Opportunities for Teaching workbook is not just about sustainability, in and of itself. It is just a part of a larger sustainability process that: 1) illustrates how sustainability correlates with current courses; 2) provides interdisciplinary opportunities for teaching; 3) equips students with a basic understanding of sustainability in the world and the workforce; and 4) improves students’ critical thinking skills. Sustainability has been a part of higher education for many years in the form of energy and water efficiencies, waste minimization and recycling initiatives. More recently, the inclusion of green building programs such as LEED have broadened the scope of campus sustainability efforts. This workbook was written and designed to serve as a link between col- lege courses and a broad range of sustainability issues. The Sustainability: Designing Interdisciplinary Opportunities for Teaching workbook is the capstone project for Lori De La Cruz, toward the award of an MA in Sustainability and Development from Southern Methodist Uni- versity in Dallas, Texas. Referenced Web Articles Throughout the workbook, links are provided to more information and current events relating to the topic being discussed. -

Environmental Impact Ing the Key Fu Nction of Evaluating Environmental Statements

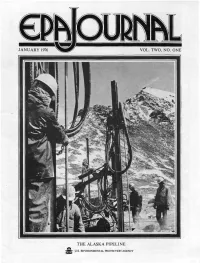

THE ALASKA PI PELI NE ft s..Tt U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY ENVIRONMENT AL IMPACT Six years ago the National Environmental Policy role EPA, as th e principal Federal regulator of Act, often de cribed as one of the most significant pollution control matters. ha pl ayed in reviewing Jaws of thi century, was signed. proposed actions and seeking to reduce environmen T hi s act imposes a number of requirements, tal damage from these project . including o ne which has achi eved wide fame and The group within E PA responsible for coordinat some notoriety, preparation of environmental impact ing the key fu nction of evaluating environmental statements. impact statements i the Office of Federal Activities. Essentiall y this last provi ion tates that whenever EPA's regions and program offi ce all play a role in a Federal agency proposes to take a major action the review process. having a ignifi cant effect on the quality of the Also reviewed in this issue are some of the other human environment. it must prepare a detailed responsibilities of this Office. such as helping to tatement on the environmental effects. ensure that Federal facil ities curb their own pollution. This law i regarded by some as an extraordinar il y aiding America's Indians in their efforts to protect effective environmental measure which has revolu their environment and helping with a traini ng pro tionized Federal decision-making. Others view it as a gram which finds jobs in the environmental area for tool for obstruction and a giant paperwork machine. -

Art and Archives

Art and Archives 3a. The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, 1931 I. Related Documents from the National Archives Note: To access documents from the National Archives Catalog: a) Click on the link provided and Select the “Digital Copies” tab OR b) Visit http://www.archives.gov/research/search/ and enter the Identifier # Painting depicting the midnight ride of Paul Revere:artist A.L. Ripley:Lexington branch post office: Massachusetts, ca. 1937 National Archives Identifier 196560 http://arcweb.archives.gov/arc/action/ExternalIdSearch?id=196560 Paul Revere's ride National Archives Identifier 535721 http://arcweb.archives.gov/arc/action/ExternalIdSearch?id=535721 Pictures of the Revolutionary War http://www.archives.gov/research/military/american-revolution/pictures/index.html www.archives.gov/northeast/nyc/education 1 | Page Art and Archives Deposition of John Robins Regarding Hostilities at Lexington: 04/24/1775 National Archives Identifier 1663351 http://arcweb.archives.gov/arc/action/ExternalIdSearch?id=1663351 Deposition of Captain John Parker Concerning the Battle at Lexington: 04/25/1775 National Archives Identifier 595243 http://arcweb.archives.gov/arc/action/ExternalIdSearch?id=595246 II. Suggested Activities 1. Compare and Contrast: Compare and Contrast the Grant Wood painting of Paul Revere’s Ride with the two paintings of Paul Revere’s ride listed above (National Archives Identifiers 196560 and 535721). What are the major similarities and differences between their depictions of Paul Revere and his ride? 2. Further Research: How have artists commemorated the American Revolution? Analyzing images from the Pictures of the Revolutionary War webpage above, choose five paintings that you feel best represent the American Revolution. -

LCI Calculation Tools for Regionalised Waste Treatment – General Introduction

LCI calculation tools for regionalised waste treatment – General introduction Technical report Zurich, September 2017 Gabor Doka Doka Life Cycle Assessments, Zurich Author Gabor Doka, Doka LCA, Zurich, [email protected] Review Ivan Muñoz of 2.-0 LCA consultants Title picture Waste dump in Jefferson County, Denver county, CO, United States in April 1972. As a reminder that rather informal disposal methods were commonplace also in developed countries not so long ago. Photo by Bruce McAllister, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency from the Documerica-1 Exhibition. Public Domain from Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:JEFFERSON_COUNTY_DUMP._(FROM_THE_DOCUMERICA- 1_EXHIBITION_FOR_OTHER_IMAGES_IN_THIS_ASSIGNMENT,_SEE_FICHE_NUMBERS_38..._-_NARA_- _553039.jpg (10 Jul 2017) Disclaimer The information contained in this report were carefully elaborated and compiled by the author according to best knowledge and available data. Due to the broad scope of the task and the inherently variable nature of the subject, errors or deviations cannot be excluded. For this reason the information contained in this report is provided without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including but not limited to the fitness for a particular purpose. In no event shall the author, Doka Life Cycle Assessments or the commissioner be liable for any claim, damages or other liability, arising from the use, application or dissemination of this information. Significant digits Figures in this report often feature several digits. This is not to imply that all the shown digits are really significant or that the data displayed is very precise. Showing several digits helps to minimise the avoidable accumulation of rounding mistakes along the chain of calculations performed here, and in possible future studies referring to this data. -

1977 1 110 P. Stone

AeNMCv FOR IWNTrATIONAL. oIVw.OPugNI FOR AID USE ONLY I WAINSINTOW. 0. C. joaes 9ISLIGRAPINC INPUT SHEET BATCH 53 I- SUBJECT A.PIAYTEMPORARY CLAW-. FICATI@ON ICNOU L TITLE AND SUBTITLE Industrial pollution control, executive summary AUTHOR($) (101) Stone, Ralph & Co., Los Angeles 4. DOCUMENT DATE S. NUMBER OF PAGES SARC NUMBER 1977 1 110 p. AMC 7. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION NAME AND Stone ADDRESS 6. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (Sponeoring Organisatlon# Publishers, Avallability) 9. ABSTRACT (Scionce & Technology--ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING R&D) Government leaders, industrialists, and concerned individuals with differing technical and national backgrounds are often called on to formulate policy governing the control of Industrial pollutants. This report facilitates that task. It focuses on the growing price of Industrial pollution and the way society pays -- either by paying to prevent pollution, or paying its price in contaminated fields and waters, corrosion, and increased human suffering -- and on strategies government and industry can use to control polluting discharges (these strategies are well documented with tables). Also described are the respective cost-benefits of industrial freedom to pollute, and mandatory pollution control. Information sources and a complete glossary are included in the summary. 10. CONTROL NUMBER II. PRICE OF DOCUMENT PN-AAD-070 12. DESCRIPTORS IS. PROJECT NUMBER 14. CONTRACT NUMBER AID/ta-C-1091 GTS IS.TYPE OF DOCUMENT AID 890-1 1474) INDUSTIAL POLLUTION CONTROL VOUME 1: EXECU1VE SUMMARY MR STOLE ANO COMPANY INC. LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA, USA INDUSTRIAL POLLUTION CONTROL I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, APRIL 1977 By R.PALPI STONE & CO., INC. 11954 SANTA MONICA BLVD. LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .- Acknowledgments iv 1. -

Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Works Cited Primary Sources: Archival Collections "Archives of American Art." Oral History Interview with Dorothea Lange, 1964 May 22. Smithsonian Institution, n.d. Web. 08 Feb. 2016. The Archives of American Art proved to be an extremely useful resource for our project due to the mass collection of oral and transcribed interviews, as well as the stark images that accompanied them. The transcribed interview with FSA photographer, Dorothea Lange was the most beneficial to our group because we were able to see a new side of her and the true honesty that she held throughout the culmination of the FSA photography project. "Documenting America, 19351943: The Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photo Collection with Carl Fleischhauer." Journeys and Crossings, Library of Congress Digital Reference Section, n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2016. This source provided our group with numerous images of not only the Farm Security Administration's collection of photographs, but also with some of the Office Of War photographs. The photographs that were taken under the Office of War Information's supervision are in color because during this time period when the United States was entering World War Two, color photography became increasingly popular. Our group used a couple of these images in our documentary to describe the transformation of the FSA photographers to the OWI initiatives. "FSA Years." Arthur Rothstein Archive. Ann RothsteinSegan, Brodie Hefner, n.d. Web. 8 Feb. 2016. This online archive was helpful to our group because we were able browse through a wide variety of FSA photography project images and select the most useful ones to use in our documentary.