Peters Draft for Discussion—Not for Quotation Or Citation 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More!

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More! Grade Level: 3rd -5 th Objectives: Students will construct their own meaning from a variety of legends and myths about dolphins and then create their own dolphin legend or myth. Florida Sunshine State Standards: Language Arts LA.A.2.2.5 The student reads and organizes information for a variety of purposes, including making a report, conducting interviews, taking a test, and performing an authentic task. LA.B.1.2 The student uses the writing processes effectively. Social Studies SS.A.1.2.1: The student understands how individuals, ideas, decisions, and events can influence history. SS.B.2.2.4: The student understands how factors such as population growth, human migration, improved methods of transportation and communication, and economic development affect the use and conservation of natural resources. Science SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. National Science Education Standards: Content Standard C (K-4) - Characteristics of Organisms : Each plant or animal has different structures that serve different functions in growth, survival, and reproduction. For example, humans have distinct body structures for walking, holding, seeing, and talking. Content Standard C (5-8) - Diversity and adaptations of Organisms : Biological evolution accounts for the diversity of species developed through gradual processes over many generations. Species acquire many of their unique characteristics through biological adaptation, which involves the selection of naturally occurring variations in populations. Biological adaptations include changes in structures, behaviors, or physiology that enhance survival and reproductive success in a particular environment. -

Cognitive Adaptations of Social Bonding in Birds Nathan J

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2007) 362, 489–505 doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1991 Published online 24 January 2007 Cognitive adaptations of social bonding in birds Nathan J. Emery1,*, Amanda M. Seed2, Auguste M. P. von Bayern1 and Nicola S. Clayton2 1Sub-department of Animal Behaviour, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 8AA, UK 2Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EB, UK The ‘social intelligence hypothesis’ was originally conceived to explain how primates may have evolved their superior intellect and large brains when compared with other animals. Although some birds such as corvids may be intellectually comparable to apes, the same relationship between sociality and brain size seen in primates has not been found for birds, possibly suggesting a role for other non-social factors. But bird sociality is different from primate sociality. Most monkeys and apes form stable groups, whereas most birds are monogamous, and only form large flocks outside of the breeding season. Some birds form lifelong pair bonds and these species tend to have the largest brains relative to body size. Some of these species are known for their intellectual abilities (e.g. corvids and parrots), while others are not (e.g. geese and albatrosses). Although socio-ecological factors may explain some of the differences in brain size and intelligence between corvids/parrots and geese/albatrosses, we predict that the type and quality of the bonded relationship is also critical. Indeed, we present empirical evidence that rook and jackdaw partnerships resemble primate and dolphin alliances. Although social interactions within a pair may seem simple on the surface, we argue that cognition may play an important role in the maintenance of long-term relationships, something we name as ‘relationship intelligence’. -

Mute's Chronicle

Mute's Chronicle. PRINTED AND PUBLISHED AT THE OHIO INSTITUTION FOB THE DEAF AND DUMB. Vol. V.] COL.U91BVS, O., SATURDAY, JANUARY 11, 1ST3. [No. 17. The Philosophy officer. sufficient quantity of ice will unques rom his department in confusion and oil Shopping. The current cry of the British beefs tionably solve the difficulty. In Russia panic. His "Roughing It" is wholly in It is poor economy or, rather, no econo eaters, like poor little Oliver Twist asking ninety live per cent of the beef consumed ferior to his other book, though it has sold my at all to purchase inferior fabrics be for "more,' 1 recalls SOUK- interesting fact- in St. Petersburg and Moscow is fro/.en largely. The public, are wearying of him a cause they are cheap. Persons in limited eoneorning animal food and itsrehilion to beef. Fresh beef costs more, though it is little and he must arouse himself if he circumstances often commit this error, civilization. It. has marked eras of nation- all comparatively cheap, but the pref cares for his laurels. if a calico at ten cents a yard looks about :i! progress and formed the basis of aristo erence for fresh beef ov >r frox.cn is not so Bret, Hart conquered attention by his as well as one nt twelve or fifteen cent-, crat!''distinction, and \vliere monopoliz great as to prevent a purchaser from choos extraordinary talcs in the Oarlanil and the prudent purchaser will often think i; ed hy a guild, as in the Klorentiiu; llo- ing a prime bit of the latter over a sec grew celebrated by his trille, "The Hea economy to choose' the low-priced goods. -

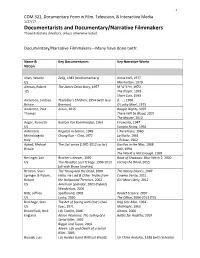

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Books, Films, and Medical Humanities

Books, Films, and Medical Humanities Films 50/50, 2011 Amour, 2012 And the Band Played On, 1993 Awakenings, 1990 Away From Her, 2006 A Beautiful Mind, 2001 The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, 2007 In The Family, 2011 The Intouchables, 2011 Iris, 2001 My Left Foot, 1989 One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975 Philadelphia, 1993 Rain Man, 1988 Silver Linings Playbook, 2012 The Station Agent, 2003 Temple Grandin, 2010 21 grams, 2003 Patch Adams, 1998 Wit, 2001 Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story, 2009 Awake, 2007 Something the Lord Made, 2004 Medicine Man, 1992 The Doctor, 1991 The Good Doctor, 2011 Side Effects, 2013 Books History/Biography Elmer, Peter and Ole Peter Grell, eds. Health, disease and society in Europe, 1500-1800: A Source Book. 2004. Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. 1963. 1 --Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. 1964. Gilman, Ernest B. Plague Writing in Early Modern England. 2009. Harris, Jonathan Gil. Foreign Bodies and the Body Politic: Discourses of Social Pathology in Early Modern England. 1998. Healy, Margaret. Fictions of Disease in Early Modern England: Bodies, Plagues and Politics. 2001. Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. 1999. Markel, Howard. An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. 2011. Morris, David B. The Culture of Pain. 1991. Moss, Stephanie and Kaara Peterson, eds. Disease, Diagnosis and Cure on the Early Modern Stage. 2004. Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. 2010. Newman, Karen. -

Johannes Ulf Lange Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology [email protected], Johannesulf.Github.Io

Johannes Ulf Lange Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology [email protected], johannesulf.github.io RESEARCH INTERESTS Cosmology, Large-Scale Structure, Weak Gravitational Lensing, Galaxy-Halo Connection, Galaxy Formation Theory, Statistical Methods and Machine Learning EDUCATION Yale University 08/2014 – 08/2019 M.Sc., M.Phil, Ph.D. in Astronomy Thesis Advisor: Frank van den Bosch Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 09/2012 – 08/2014 Master of Science in Physics Freie Universität Berlin 10/2009 – 08/2012 Bachelor of Science in Physics POSITIONS Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology 09/2021 – 08/2023 Stanford–Santa Cruz Cosmology Postdoctoral Fellow University of California, Santa Cruz 09/2019 – 08/2021 Stanford–Santa Cruz Cosmology Postdoctoral Fellow FIRST-AUTHOR PUBLICATIONS [10] J. U. Lange, A. P. Hearin, A. Leauthaud, F. C. van den Bosch, H. Guo, and J. DeRose. “Five-percent measurements of the growth rate from simulation-based mod- elling of redshift-space clustering in BOSS LOWZ”. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2101.12261 (Jan. 2021), arXiv:2101.12261. [9] J. U. Lange, A. Leauthaud, S. Singh, H. Guo, R. Zhou, T. L. Smith, and F.-Y. Cyr- Racine. “On the halo-mass and radial scale dependence of the lensing is low effect”. MNRAS 502.2 (Apr. 2021), pp. 2074–2086. [8] J. U. Lange, F. C. van den Bosch, A. R. Zentner, K. Wang, A. P. Hearin, and H. Guo. “Cosmological Evidence Modelling: a new simulation-based approach to constrain cosmology on non-linear scales”. MNRAS 490.2 (Dec. 2019), pp. 1870–1878. [7] J. U. Lange, X. Yang, H. Guo, W. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

Alice Meynell

Poems Alice Meynell The Project Gutenberg eBook, Poems, by Alice Meynell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Poems Author: Alice Meynell Release Date: March 16, 2005 [eBook #1186] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS*** Transcribed from the 1903 John Lane edition by David Price, email [email protected] Poems by Alice Meynell Contents: SONNET--MY HEART SHALL BE THY GARDEN SONNET--THOUGHTS IN SEPARATION TO A POET SONG OF THE SPRING TO THE SUMMER TO THE BELOVED MEDITATION TO THE BELOVED DEAD--A LAMENT SONNET Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. IN AUTUMN A LETTER FROM A GIRL TO HER OWN OLD AGE SONG BUILDERS OF RUINS SONNET SONG OF THE DAY TO THE NIGHT 'SOEUR MONIQUE' IN EARLY SPRING PARTED REGRETS SONG SONNET--IN FEBRUARY SAN LORENZO GIUSTINIANI'S MOTHER SONNET--THE LOVE OF NARCISSUS TO A LOST MELODY SONNET--THE POET TO NATURE THE POET TO HIS CHILDHOOD SONNET AN UNMARKED FESTIVAL SONNET--THE NEOPHYTE SONNET--SPRING ON THE ALBAN HILLS SONG OF THE NIGHT AT DAYBREAK SONNET--TO A DAISY SONNET--TO ONE POEM IN A SILENT TIME FUTURE POETRY THE POET SINGS TO HER POET A POET'S SONNET THE MODERN POET AFTER A PARTING RENOUNCEMENT VENI CREATOR DEDICATION TO W. -

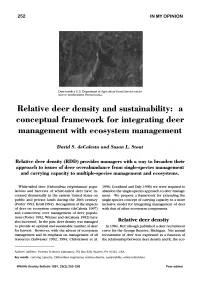

Relative Deer Density and Sustainability: a Conceptual Framework for Integrating Deer Management with Ecosystem Management

252 IN MY OPINION Deer inside a U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service enclo sure in northwestern Pennsylvania. Relative deer density and sustainability: a conceptual framework for integrating deer management with ecosystem management David S. deCalesta and Susan L. Stout Relative deer density (RDD) provides managers with a way to broaden their approach to issues of deer overabundance from single-species management and carrying capacity to multiple-species management and ecosystems. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) popu 1996; Goodland and Daly 1996) we were required to lations and harvests of white-tailed deer have in abandon the single-species approach to deer manage creased dramatically in the eastern United States on ment. We propose a framework for extending the public and private lands during the 20th century single-species concept of carrying capacity to a more (Porter 1992, Kroll 1994). Recognition of the impacts inclusive model for integrating management of deer of deer on ecosystem components ( deCalesta 1997) with that of other ecosystem components. and controversy over management of deer popula tions (Porter 1992, Witmer and deCalesta 1992) have also increased. In the past, deer density was managed Relative deer density to provide an optimal and sustainable number of deer In 1984, McCullough published a deer recruitment for harvest. However, with the advent of ecosystem curve for the George Reserve, Michigan. Net annual management and its emphasis on management of all recruitment of deer was expressed as a function of resources (Salwasser 1992, 1994; Christenson et al. the relationship between deer density and K, the eco- Authors' address: Forestry Sciences Laboratory, PO Box 928, Warren, PA 16365, USA. -

Innovation Policy Pluralism Abstract

DANIEL J. HEMEL & LISA LARRIMORE OUELLETTE Innovation Policy Pluralism abstract. When lawyers and scholars speak of “intellectual property,” they are generally referring to a combination of two distinct elements: an innovation incentive that promises a market- based reward to producers of knowledge goods, and an allocation mechanism that makes access to knowledge goods conditional upon payment of a proprietary price. Distinguishing these two ele- ments clarifies ongoing debates about intellectual property and opens up new possibilities for in- novation policy. Once intellectual property is disaggregated into its core components, each element can be combined synergistically with non-IP innovation incentives such as prizes, tax preferences, and direct spending on grants and government research, or with non-IP allocation mechanisms that promote broader access to knowledge goods. In this Article, we build a novel conceptual framework for analyzing combinations of IP and non-IP policy mechanisms and present a new vocabulary to characterize those combinations. Matching involves the pairing of an IP incentive with a non-IP allocation mechanism—or, vice versa, the pairing of a non-IP incentive with IP as an allocation strategy. Mixing entails the use of IP and non-IP tools on the same side of the incentive/allocation divide: i.e., the use of both IP and non-IP innovation incentives, or of IP and non-IP allocation mechanisms. Layering refers to the use of different policies at different jurisdictionallevels, such as using non-IP innovation incentives and allocation mechanisms at the domestic level within an international legal system oriented around IP. After setting forth this framework, we identify reasons why different combinations of IP and non-IP tools may be optimal in specific circumstances. -

Yale French Studies Structuralism

Yale French Studies Structuralism Double Issue - Two Dollars Per Copy - All ArticlesIn English This content downloaded from 138.38.44.95 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 19:52:13 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Yale French Studies THIRTY-SIX AND THIRTY-SEVEN STRUCTURALISM 5 Introduction The Editor LINGUISTICS 10 Structureand Language A ndreMartinet 19 Merleau-Pontyand thephenomenology of language PhilipE. Lewis ANTHROPOLOGY 41 Overtureto le Cru et le cuit Claude Levi-Strauss 66 Structuralismin anthropology Harold W. Scheffler ART 89 Some remarkson structuralanalysis in art and architecture SheldonNodelman PSYCHIATRY 104 JacquesLacan and thestructure of the unconscious JanMiel 112 The insistenceof the letterin the unconscious JacquesLacan LITERATURE 148 Structuralism:the Anglo-Americanadventure GeoffreyHartman 169 Structuresof exchangein Cinna JacquesEhrmann 200 Describingpoetic structures: Two approaches to Baudelaire'sles Chats Michael Riffaterre 243 Towards an anthropologyof literature VictoriaL. Rippere This content downloaded from 138.38.44.95 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 19:52:13 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BIBLIOGRAPHIES 252 Linguistics ElizabethBarber 256 Anthropology Allen R. Maxwell 263 JacquesLacan AnthonyG. Wilden 269 Structuralismand literarycriticism T. Todorov 270 Selectedgeneral bibliography The Editor Cover: "Graph,"photograph by JacquesEhrmann. Editor, this issue: Jacques Ehrmann; Business Manager: Bruce M. Wermuth; General Editor: Joseph H. McMahon; Assistant: Jonathan B. Talbot; Advisory Board: Henri Peyre (Chairman), Michel Beaujour, Victor Brombert, Kenneth Cornell, Georges May, Charles Porter Subscriptions:$3.50 for two years (four issues), $2.00 for one year (two issues), $1.00 per number.323 W. L. HarknessHall, Yale University,New Haven, Connecticut.Printed for YFS by EasternPress, New Haven. -

Five Minutes with Jeffrey C. Alexander: “Southern European Countries Are

Five minutes with Jeffrey C. Alexander: “Southern European countries are not just experiencing an economic crisis, but also an identity crisis” blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/04/23/five-minutes-with-jeffrey-c-alexander-europe-dark-side-of-modernity/ 4/23/2013 Is there a ‘dark side’ to European modernity? As part of our ‘ Thinkers on Europe’ series, EUROPP’s editors Stuart A Brown and Chris Gilson spoke to Jeffrey C. Alexander about his views on modernity, the European integration process, and the importance of cultural and political symbols to European democracy. You’ve written about the ‘dark side’ of modernity. What is the dark side to European modernity? Well the dark side is the disappointing, dangerous side to modernity, not to mention the murder and wars. There’s a strong narrative of progress that’s associated with the idea of modernity, although it depends when you think modernity started. You might start with the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Industrial Revolution, or the Scientific Revolution, but I wanted to put “The Dark Side of Modernity” together to crystalise the idea that there has always been a dark part that offers a kind of counterpoint to the light part. And in Europe of course we think of the first half of the 20th century as a devastating period both in terms of the birth of total war and genocide. I describe modernity as ‘Janus faced’. The god Janus was a Roman god that was associated with the creation of order in the universe, but there was also the idea that disorder was always close behind.