Phonology of the Iranian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

The Iranian Reflexes of Proto-Iranian *Ns

The Iranian Reflexes of Proto-Iranian *ns Martin Joachim Kümmel, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena [email protected] Abstract1 The obvious cognates of Avestan tąθra- ‘darkness’ in the other Iranian languages generally show no trace of the consonant θ; they all look like reflexes of *tār°. Instead of assuming a different word formation for the non-Avestan words, I propose a solution uniting the obviously corresponding words under a common preform, starting from Proto-Iranian *taNsra-: Before a sonorant *ns was preserved as ns in Avestan (feed- ing the change of tautosyllabic *sr > *θr) but changed to *nh elsewhere, followed by *anhr > *ã(h)r. A parallel case of apparent variation can be explained similarly, namely Avestan pąsnu- ‘ashes’ and its cog- nates. Finally, the general development of Proto-Indo-Iranian *ns in Iranian and its relative chronology is discussed, including word-final *ns, where it is argued that the Avestan accusative plural of a-stems can be derived from *-āns. Keywords: Proto-Iranian, nasals, sibilant, sound change, variation, chronology 1. Introduction The aim of this paper is to discuss some details of the development of the Proto- Iranian (PIr) cluster *ns in the Iranian languages. Before we proceed to do so, it will be useful to recall the most important facts concerning the history of dental-alveolar sibilants in Iranian. 1) PIr had inherited a sibilant *s identical to Old Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit/Vedic) s from Proto-Indo-Iranian (PIIr) *s. This sibilant changed to Common Iranian (CIr) h in most environments, while its voiced allophone z remained stable all the time. -

Pre-Proto-Iranians of Afghanistan As Initiators of Sakta Tantrism: on the Scythian/Saka Affiliation of the Dasas, Nuristanis and Magadhans

Iranica Antiqua, vol. XXXVII, 2002 PRE-PROTO-IRANIANS OF AFGHANISTAN AS INITIATORS OF SAKTA TANTRISM: ON THE SCYTHIAN/SAKA AFFILIATION OF THE DASAS, NURISTANIS AND MAGADHANS BY Asko PARPOLA (Helsinki) 1. Introduction 1.1 Preliminary notice Professor C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky is a scholar striving at integrated understanding of wide-ranging historical processes, extending from Mesopotamia and Elam to Central Asia and the Indus Valley (cf. Lamberg- Karlovsky 1985; 1996) and even further, to the Altai. The present study has similar ambitions and deals with much the same area, although the approach is from the opposite direction, north to south. I am grateful to Dan Potts for the opportunity to present the paper in Karl's Festschrift. It extends and complements another recent essay of mine, ‘From the dialects of Old Indo-Aryan to Proto-Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian', to appear in a volume in the memory of Sir Harold Bailey (Parpola in press a). To com- pensate for that wider framework which otherwise would be missing here, the main conclusions are summarized (with some further elaboration) below in section 1.2. Some fundamental ideas elaborated here were presented for the first time in 1988 in a paper entitled ‘The coming of the Aryans to Iran and India and the cultural and ethnic identity of the Dasas’ (Parpola 1988). Briefly stated, I suggested that the fortresses of the inimical Dasas raided by ¤gvedic Aryans in the Indo-Iranian borderlands have an archaeological counterpart in the Bronze Age ‘temple-fort’ of Dashly-3 in northern Afghanistan, and that those fortresses were the venue of the autumnal festival of the protoform of Durga, the feline-escorted Hindu goddess of war and victory, who appears to be of ancient Near Eastern origin. -

Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans

3 (2016) Miscellaneous 1: A-V Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans TRAVIS D. WEBSTER Center for Traditional Vedanta, USA © 2016 Ruhr-Universität Bochum Entangled Religions 3 (2016) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v3.2016.A–V Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans TRAVIS D. WEBSTER Center for Traditional Vedanta ABSTRACT Recent archaeological evidence and the comparative method of Indo-European historical linguistics now make it possible to reconstruct the Aryan migrations into India, two separate diffusions of which merge with elements of Harappan religion in Asko Parpola’s The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization (NY: Oxford University Press, 2015). This review of Parpola’s work emphasizes the acculturation of Rigvedic and Atharvavedic traditions as represented in the depiction of Vedic rites and worship of Indra and the Aśvins (Nāsatya). After identifying archaeological cultures prior to the breakup of Proto-Indo-European linguistic unity and demarcating the two branches of the Proto-Aryan community, the role of the Vrātyas leads back to mutual encounters with the Iranian Dāsas. KEY WORDS Asko Parpola; Aryan migrations; Vedic religion; Hinduism Introduction Despite the triumph of the world-religions paradigm from the late nineteenth century onwards, the fact remains that Indologists require more precise taxonomic nomenclature to make sense of their data. Although the Vedas are widely portrayed as the ‘Hindu scriptures’ and are indeed upheld as the sole arbiter of scriptural authority among Brahmins, for instance, the Vedic hymns actually play a very minor role in contemporary Indian religion. -

Classification of Eastern Iranian Languages

62 / 2014 Ľubomír Novák 1 QUESTION OF (RE)CLASSIFICATION OF EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES STATI – ARTICLES – AUFSÄTZE – СТАТЬИ AUFSÄTZE – ARTICLES – STATI Abstract The Eastern Iranian languages are traditionally divided into two subgroups: the South and the North Eastern Iranian languages. An important factor for the determination of the North Eastern and the South Eastern Iranian groups is the presence of isoglosses that appeared already in the Old Iranian period. According to an analysis of isoglosses that were used to distinguish the two branches, it appears that most likely there are only two certain isoglosses that can be used for the division of the Eastern Iranian languages into the two branches. Instead of the North-South division of the Eastern Iranian languages, it seems instead that there were approximately four dialect nuclei forming mi- nor groups within the Eastern Iranian branch. Furthermore, there are some languages that geneti- cally do not belong to these nuclei. In the New Iranian period, several features may be observed that link some of the languages together, but such links often have nothing in common with a so-called genetic relationship. The most interesting issue is the position of the so-called Pamir languages with- in the Eastern Iranian group. It appears that not all the Pamir languages are genetically related; their mutual proximity, therefore, may be more sufficiently explained by later contact phenomena. Keywords Eastern Iranian languages; Pamir languages; language classification; linguistic genealogy. The Iranian languages are commonly divided into two main groups: the Eastern and Western Iranian languages. Each of the groups is subsequently divided in two other subgroups – the Northern and Southern1. -

Manali Project Prospectus

Manali Project Prospectus Brief Overview and Areas for Further Research (April, 2017) Contents A. Description of Manali Project B. Overview of Story (as currently envisioned) C. Effort to Highlight Ways of Creating Unprecedented Culture Change, Cultivating Spiritual Wisdom D. Areas for Further Research A. Description of Project The Manali Project is a fictionalized account of three story lines taking place in a time period of from maybe 2080-2150. Hopefully, the story lines would highlight—through both dramatic and everyday circumstances-- 1) the positive possibilities associated with permaculture, appropriate technology 2) the humor associated with salvaging material culture from the previous “advanced” civilization --and share much about ways to create unprecedented culture change, and arrive at communities which integrate spiritual wisdom into the everyday circumstances of daily life. Note: (the name Manali is taken from the name of a town in India)…“Manali is named after the Sanatan Hindu lawgiver Manu. The name Manali is regarded as the derivative of 'Manu-Alaya' which literally means 'the abode of Manu'. Legend has it that sage Manu stepped off his ark in Manali to recreate human life after a great flood had deluged the world.” (Wikipedia) Questions which this fictional account seeks to explore include “what is wisdom?”, and “how does cultural transmission of wisdom take place?”. There will also be an effort to be realistic about what kind of material culture each of the three story lines have. Included below are some sources which I have identified as starting points for giving the three story lines authentic material cultures. However, this kind of writing involves more research than what I’ve done before, and so I’m looking for ideas about how to develop the material culture piece of it. -

Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin by J

Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin by j. p. mallory he earliest accounts of the Tarim Basin depict Tocharian. If his travels took him south to Khotan, he would a society whose linguistic and ethnic diversity have to deal in Khotanese Saka. Here, if he had been captured rivals the type of complexity one might oth- by a raider from the south, he would have had to talk his way erwise encounter in a modern transportation out of this encounter in Tibetan or hoped for rescue from an hub. The desert sands that did so much to army that spoke Chinese. He could even have bumped into Tpreserve the mummies, their clothes, and other grave goods a Jewish sheep merchant who spoke Modern Persian. And if also preserved an enormous collection of documents, written he knew which way the wind was blowing, he would have his on stone, wood, leather, or— employing that great Chinese invention—paper. A German expedition to the Tarim Basin in the early 20th century returned with texts in 17 differ- ent languages. We can get some appre- ciation of the linguistic com- plexity if we put ourselves in the place of a traveling mer- chant working the Silk Road in the 8th century CE. A typi- cal trader from the West may have spoken Sogdian at home. He may have visited Buddhist monasteries where the liturgi- cal language would have been Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, but the day-to-day language was , Berlin, D. Reimer, 21. Chotscho West meets East at Bezeklik in the 9th to 10th century CE. -

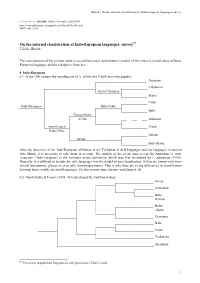

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3. -

North-West Indo-European

North-West Indo-European First draft Carlos Quiles, Fernando López-Menchero North-West Indo-European First draft Carlos Quiles, Fernando López-Menchero ACADEMIA PRISCA Spain October 2017 Version 1 - Draft (October 2017) © 2017 by Carlos Quiles [email protected] © 2017 by Fernando López-Menchero [email protected] ACADEMIA PRISCA Carlos Quiles has written the draft of all articles and approved the final manuscript. Fernando López-Menchero has corrected the initial draft of Laryngeal loss and vocalism in North-West Indo-European, written the whole section Laryngeal reflexes in North- West Indo-European, and corrected the initial draft of The three-dorsal theory. Official site: <https://academiaprisca.org/> Full text and last version: <https://oldeuropean.org/> How to cite this paper: Quiles, C., López-Menchero, F. (2017). North-West Indo-European. Badajoz, Spain: Academia Prisca. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.28327.65445 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/→ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Preface This monograph is an evolving collection of papers relevant to the reconstruction of the language of a close community of speakers, demonstrated by recent genetic studies to be related to the peoples that expanded with the Yamna culture into central Europe, its transformation into the East Bell Beaker culture, and its -

Tocharians and the Tarim Mummies

Illll r ~ TOC"'~"'T"«,", ""ltlcm"nl5dndc<"",~[i"'()f'hc:SibaculfUre.3nE..lyBronz<Asecul,ure fmd ,heir ongm. in word. f'om Gnndhlrl (rhe language of ASok.·, II I who«phy.i"allYpeWOUld3ppeortc,hc:Mongolo1d,lntheS<lmererri,ory m,criptlom) of thelnd century BCtO rhe4,hcenrury AD, where we would lare, expectthe Yuc>hi. The only wa~ we can d'5<1W Yuozhi Tochnn.n'pocinli.ts.regener.llyre!uc,an,ro.dm",har,h.",wa. 11,1 "",<l<,end tbe name over much hro.der area. of ,heT.tlrn and Turpan any flow of Indo-Iranian vocabulary Into Tochan.n e.rlier than the !>,,,,n' ,han 'he h..ro",:,,1 record,aUow. We.re engaged In mOl'mgMme. 1" millenmum Be,. mnewhen words such as Tochanan A porat, Tocha"an r aero" a map wlIhou, any evid=of 'he people. If 'he Chine.., histo,,,,s Bperel'a",,'ruayhavebeenborrowedfmmKlmelranlanlanguage(wehnd had never mtnnoned rhe YueUl1 on the bord... of Ch,n., noorchacologi" O,serle fariit 'axe')_ Tochari.:!n al,o employs a word for 'oron' (A ancu, B i wouldhavehadtheshgh'''''reasonropo'lUlarc,heirexiSfenco TheYue,h, "ricUIlIO) whICh 'Ome compare wah .imilar word, .uch os O..otic ~~d4n "re'ghosr.".uromonedupbyh"rorian,rorormentarchaeolosm,.'Weh.ve 'stU:I'.While.u,hev,deoceeanonlybeemployedpo.invely,i.o.i,cannor no need to look for ghost>; we have the remain' of ",.1 ~ople w!th ade"", demonstrate'h.t~on..c..didnotexl..,rhe",ha~beenfewto.ugge",ha, ,omeeviden"eof,hn,m.to,ia]cuJEbre. ,hoancestorso[,hoTochar""uW<:relndo>econ",,,with,ho,,lndo-lranian netghboun;beforec.l000--500ac.Togobackanyearlierrake.u,inroone Lingui.ticPrehi.wry oflh.mostd"pured~<ea.ofTocharian"udies is iu The prec<ding,enrenc. -

The Case of the Greater Iranian Peoples

American International Journal of Social Science Vol. 8, No. 1, March 2019 doi:10.30845/aijss.v8n1p1 Languages as a Shared Cultural Heritage: the Case of the Greater Iranian Peoples Mitra Ara. Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Modern Languages and Literatures San Francisco State University 1600 Holloway Avenue San Francisco, CA 94132, USA Abstract This article suggests adopting common approaches in introducing languages and peoples as one social group with shared ancestry, homeland, cultures, and languages. By examining this complex relationship among language, ethnicity, nationality, and how people define themselves culturally through a historical examination of the languages and peoples of the Greater Iran (Central and West Asia) as one social group with shared ancestry, homeland, cultures, and languages, the article further argues that a common approach will help to correct the mis-labeling of and mis- conceptions about these languages, and encourage greater understanding. The history and materials provided in the article are intended to help illustrate how a better recognition of the past while strengthening present relations among any cultural group, such as the Iranian peoples, can form a peaceful connection for the future. Keywords: Iranian peoples, Ethnic and National Identity, West and Central Asia, Greater Iran, common approaches to language. 1. Introduction Using the Greater Iranian peoples as a case study brings to light the responsibility and importance of adopting and advocating common approaches in introducing languages and peoples as one social group that shares ancestry, homeland, cultures, and languages. As a result of globalization, Iranian peoples have scattered, living both in home countries and in the diaspora. -

Indo-Iranian Loanwords in the Uralic Languages 8.4.2018 Sampsa

Indo-Iranian loanwords in the Uralic languages dictionary of the Iranian verb; Cowgill & Mayrhofer 1986: Indogermanische Grammatik I. Schmitt (ed.) 1989: Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum; Windfuhr 8.4.2018 (ed.) 2009: The Iranian languages; EWAia; KEWA Sampsa Holopainen Notable hindrance: there is no proper etymological dictionary of Iranian! [email protected] PU vowel system (initial syllables) i ü u Introduction e e̮ o ä a General information about Indo-Iranian A well-defined branch of the IE family of languages. Consists of three sub- branches: Indo-Iranian, Iranian and Nuristani (the status of the last one controversial). Proto-Indo-Iranian (PII) was spoken in Caspian steppes until ca. *e̮ is a central vowel, reconstructed as high *i̮ by Janhunen (1981) and 2000 BCE (the historical spread of Indo-Iranian is due to later migrations). Sammallahti (1988). Merger with the reflexes of PU *a in several branches, the Proto-Mansi reflex *e̮ and the substitution of Indo-Iranian *a are the main Contacts between Indo-Iranian and Uralic started at the PU/PFU period; earliest arguments for the reconstruction of this vowel as *e̮ rather than *i̮ (see Häkkinen loans reflect retained PIE vocalism (before the merger of *a, *e, *o, *m̥ , *n̥ > *a, 2009). *ā, *ē, *ō > *ā). Proto-Indo-Iranian was also in contact with other, unknown languages, which is shown by a number of words with no IE etymology (Lubotsky 2001). PII vowel system Earliest written sources on Indo-Iranian are the Indo-Aryan words and names in i, ī u, ū the Mitanni (Hurrian) documents from the late 2nd millenium BCE.