Digital Must-Carry & (And) the Case for Public Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glenn Reitmeier Component Digital Video Interface Now by the Time Testing Was Completed, All Used Worldwide

IGNITING CHANGE of a job that would allow Reitmeier to ing would determine the winner. Sarnoff “y I can’t sa enough apply advanced signal processing to TV. couldn’t pass up the challenge. Sarnoff also would send him to the Uni- An early prophet of digital TV, about the personal versity of Pennsylvania for his master’s. Reitmeier was tapped to lead the devel- attention of the Villanovans contributing to the community Reitmeier hit the ground digitizing. He opment of the Advanced Digital HDTV helped develop the architecture and soft- system for Sarnoff and its consortium faculty and their ware for one of the first computer systems partners: Philips, Thomson and NBC. dedication to for digitizing video; picked up his first pat- Competing against the calendar and new ent for picture resizing for digital video digital approaches from such titans as teaching.” effects; and contributed to experiments AT&T and MIT, Reitmeier’s team worked that led to the adoption of a standard for feverishly to build their prototype. — Glenn Reitmeier component digital video interface now By the time testing was completed, all used worldwide. This pace never slack- analog proposals had been eliminated, ened in Reitmeier’s 25 years at Sarnoff. since they couldn’t send HDTV in a single His collaboration and leadership in digi- over-the-air TV channel. But surprisingly, Their achievement earned the Grand tal video research, consumer electronics none of the four digital entries was victori- Alliance companies an Emmy Award. and other technologies earned Reitmeier ous. Each had strengths and weaknesses. Since 2002, Reitmeier has guided NBC the industry’s respect—and his children’s. -

Federal Communications Commission § 74.789

Federal Communications Commission § 74.789 In addition, any outstanding construc- (3) Applications for extension of time tion permit (analog or digital) for an shall be filed not later than May 1, channel above Channel 51 will be re- 2015, absent a showing of sufficient rea- scinded on December 31, 2011, and any sons for late filing. pending application (analog or digital) (d) For construction deadlines occur- for a channel above Channel 51 will be ring after September 1, 2015, the tolling dismissed on December 31, 2011, if the provisions of § 73.3598 of this chapter permittee has not submitted a digital shall apply. displacement application by 11:59 pm (e) A low power television, TV trans- local on September 1, 2011. lator or Class A television station that holds a construction permit for an un- [69 FR 69333, Nov. 29, 2004, as amended at 74 FR 23655, May 20, 2009; 76 FR 44828, July 27, built analog and corresponding unbuilt 2011] digital station and fails to complete construction of the analog station by § 74.788 Digital construction period. the expiration date on the analog con- struction permit shall forfeit both the (a) Each original construction permit analog and digital construction per- for the construction of a new digital mits notwithstanding a later expira- low power television or television tion date on the digital construction translator station shall specify a pe- permit. riod of three years from the date of (f) A low power television, TV trans- issuance of the original construction lator or Class A television station that permit within which construction shall holds a construction permit for an un- be completed and application for li- built analog and corresponding unbuilt cense filed. -

Replacing Digital Terrestrial Television with Internet Protocol?

This is a repository copy of The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94851/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ala-Fossi, M and Lax, S orcid.org/0000-0003-3469-1594 (2016) The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol? International Communication Gazette, 78 (4). pp. 365-382. ISSN 1748-0485 https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516632171 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Short Future of Public Broadcasting: Replacing DTT with IP? Marko Ala-Fossi & Stephen Lax School of Communication, School of Media and Communication Media and Theatre (CMT) University of Leeds 33014 University of Tampere Leeds LS2 9JT Finland UK [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Public broadcasting, terrestrial television, switch-off, internet protocol, convergence, universal service, data traffic, spectrum scarcity, capacity crunch. -

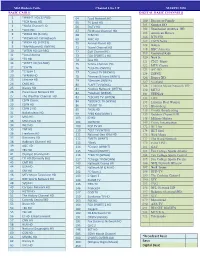

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

Public Media – Pubic Broadcasting System (PBS)

SUPPORTING PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY MEDIA ACTION NEEDED We urge Congress to: Restore public broadcasting funding to the FY 2013 appropriation level of $445 million through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). Pass the Community Access Preservation Act (CAP Act) to preserve public, educational, and governmental (PEG) non-commercial cable channels for local communities. OVERVIEW—PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY MEDIA Public media consists of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), National Public Radio (NPR), and more than 1,000 local public broadcasting stations. Community media is comprised of public, educational, and government (PEG) cable access TV and community radio stations. Both public and community media have a long history of presenting local, regional, and national nonprofit arts programming, a great majority of which is not available on commercial channels. These organizations play a unique role in bringing both classics and contemporary works to the American public. All of these systems exist because of federal funding or legislation. TALKING POINTS— CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING In creating America’s unique public broadcasting system, Congress acknowledged public broadcasting’s role in transmitting arts and culture: “It is in the public interest to encourage the growth and development of public radio and television broadcasting, including the use of such media for instructional, educational, and cultural purposes.” And Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) is the vehicle through which Congress has chosen to promote noncommercial public telecommunications. CPB does not produce or broadcast programs. The vast majority of funding through CPB goes directly to local public broadcast stations in the form of Community Service Grants. The federal portion of the average public station’s revenue is approximately 10–15 percent. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Are You Ready for Digital TV? 20 January 2009

Are you ready for digital TV? 20 January 2009 (PhysOrg.com) -- If everything goes as planned, on Q: If I install a digital converter box to my Feb. 17 the long-awaited switch from analog to television set, what will I get? digital broadcasting will take place and millions of DS: Provided that the digital converter box has a analog television sets across the nation will go reasonably good antenna, you would be able to black. Temple University electrical and computer receive the over-the-air digital signals that the engineering Professor Dennis Silage, an expert in broadcasters are transmitting; basically, your local both analog and digital communications, has television stations. You have to hook the converter answered some questions about this digital TV box up to an antenna and even a simple a ‘rabbit transition and what it will mean for consumers. ear’ antenna may work for you. We’re going back to the future, if you remember when you used to Q: Why are we switching from analog? have rabbit ear antennas on your TV and you had DS: Analog is a 60-plus-year-old technology that to play around with them to get the best picture. has basically lasted the test of time, but doesn’t Now, because of the digital conversion, your local really allow more advanced services, such as television stations also have subsidiary channels additional channels and information using the that would be very interesting to see. They may existing the broadcast spectrum. It’s not as have as many as three subsidiary channels. -

ED358828.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 828 IR 016 108 AUTHOR Thompsen, Philip A. TITLE Public Broadcasting in the New World of Digital Information Services: What's Been Done, What's Being Done, and What Could Be Done. PUB DATE May 92 NOTE 12p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association (42nd, Miami, FL, May 20-25, 1992). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Television; Educational Television; Electronic Mail; *Information Technology; *Mass Media Role; *Public Television; *Radio; Technological Advancement IDENTIFIERS Closed Captioned Television; *Digital Information Services; *Public Broadcasting ABSTRACT This paper explores the progress public broadcasting (originally called "educational television") has made in taking advantage of a relatively new application of tecnnology: digital information services. How public broadcasters have pursued this technology and how it may become an integral part of the future of public broadcasting are reviewed. Three of the more successful digital information services that have been provided by public broadcasters (i.e., closed captioning, electronic bulletin board services, and electronic text) are discussed. The paper then discusses three areas that are currently being pursued: digital radio broadcasting, interactive video data services, and the broadcasting of data over the vertical blanking interval (VBI) of public television stations. A vision for the future of public broadcasting is considered, identifying some of the important opportunities that should be taken advantage of before the rapidly changing technological environment eclipses public broadcasting's chance to define a better future for an electronic society. (Contains 39 references.) (RS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Pubic Broadcasting System (PBS), National Public Radio (NPR)

SUPPORTING PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY MEDIA ACTION NEEDED We urge Congress to: • Retain funding for public broadcasting at FY 2012 levels through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). • Pass the Community Access Preservation Act (H.R. 1746), introduced by Rep. Steven LaTourette (R- OH) and Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D- WI), to preserve public, educational, and governmental (PEG) non- commercial cable channels for local communities. Overview– Public and Community Media Public media consists of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), National Public Radio (NPR), and more than 1,000 local public broadcasting stations. Community media is comprised of public, educational, and government (PEG) cable access TV and community radio stations. Both public and community media have a long history of presenting local, regional, and national nonprofit arts programming, a great majority of which is not available on commercial channels. These organizations play a unique role in bringing both classics and contemporary works to the American public. All of these systems exist because of federal funding or legislation. Talking Points - Corporation for Public Broadcasting • In creating America’s unique public broadcasting system, Congress acknowledged public broadcasting’s role in transmitting arts and culture: “It is in the public interest to encourage the growth and development of public radio and television broadcasting, including the use of such media for instructional, educational, and cultural purposes.” And Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) is the vehicle through which Congress has chosen to promote noncommercial public telecommunications. • CPB does not produce or broadcast programs. The vast majority of funding through CPB goes directly to local public broadcast stations in the form of Community Service Grants. -

ATSC Standard: Program and System Information Protocol for Terrestrial Broadcast and Cable (Revision C) with Amendment No

A/65C 2 January 2006 Amendment No. 1 dated 9 May 2006 ATSC Standard: Program and System Information Protocol for Terrestrial Broadcast and Cable (Revision C) With Amendment No. 1 Advanced Television Systems Committee 1750 K Street, N.W. Suite 1200 Washington, D.C. 20006 http://www.atsc.org ATSC A/65C Program and System Information Protocol 2 January 2006 The Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc., is an international, non-profit organization developing voluntary standards for digital television. The ATSC member organizations represent the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. Specifically, ATSC is working to coordinate television standards among different communications media focusing on digital television, interactive systems, and broadband multimedia communications. ATSC is also developing digital television implementation strategies and presenting educational seminars on the ATSC standards. ATSC was formed in 1982 by the member organizations of the Joint Committee on InterSociety Coordination (JCIC): the Electronic Industries Association (EIA), the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), the National Cable Television Association (NCTA), and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). Currently, there are approximately 140 members representing the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. ATSC Digital TV Standards include digital high definition television (HDTV), standard definition television (SDTV), data broadcasting, multichannel surround-sound audio, and satellite direct-to-home broadcasting. NOTE: The user's attention is called to the possibility that compliance with this standard may require use of an invention covered by patent rights. By publication of this standard, no position is taken with respect to the validity of this claim or of any patent rights in connection therewith. -

Program and System Information Protocol Implementation Guidelines for Broadcasters

ATSC Recommended Practice: Program and System Information Protocol Implementation Guidelines for Broadcasters Document A/69:2009, 25 December 2009 Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc. 1776 K Street, N.W., Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20006 Advanced Television Systems Committee Document A/69:2009 The Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc., is an international, non-profit organization developing voluntary standards for digital television. The ATSC member organizations represent the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. Specifically, ATSC is working to coordinate television standards among different communications media focusing on digital television, interactive systems, and broadband multimedia communications. ATSC is also developing digital television implementation strategies and presenting educational seminars on the ATSC standards. ATSC was formed in 1982 by the member organizations of the Joint Committee on InterSociety Coordination (JCIC): the Electronic Industries Association (EIA), the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), the National Cable Telecommunications Association (NCTA), and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). Currently, there are approximately 140 members representing the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. ATSC Digital TV Standards include -

Satellite Uplinks

TOS Pt.3 PBS Technology & Operations TECHNICAL OPERATING SPECIFICATIONS Satellite Uplinks 2013 Edition 1. SCOPE AND PURPOSE This specification defines uplink performance requirements for the Public Television Interconnection System. These parameters will address the settings for uplink MPEG-4 and MPEG-2 encoders, multiplexer, DVB-S and DVB-S2 modulators, and any redundant systems. The goal is to provide consistent quality performance among multiple uplink providers serving the Public Television Satellite Interconnection System. It is essential that all parameters be set correctly. It is vital that all uplink operators meet these performance requirements and protocols. Most stations rely on consistent signals from the satellite system and member stations do not have the manpower or means to compensate for variations. This specification prescribes standards that uplink operators must meet, and informs receiving stations what signal standards they should expect. This document is especially important for uplink operators working with other satellite services, since some of these specifications are unique to the PBS system. 2. SYSTEM INFORMATION PBS currently uses transponders on satellite AMC-21 for Ku service to member stations and on satellite AMC-1 for C-Band service for home consumers. The modulation formats in use are DVB-S2 for all MCPC services and HD SCPC services and either DVB-S or DVB-S2 for all SD SCPC services. Users are encouraged to utilize DVB-S2 modulation on SD transmissions whenever possible. DVB-S2 modulation will become a requirement on all services at a future date TBD All of these services have a payload contained within a standard MPEG transport stream.