Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape, Antietam National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F9f Panther Units of the Korean War

0413&:$0.#"5"*3$3"'5t F9F PANTHER UNITS OF THE KOREAN WAR Warren Thompson © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com SERIES EDITOR: TONY HOLMES OSPREY COMBAT AIRCRAFT 103 F9F PANTHER UNITS OF THE KOREAN WAR WARREN THOMPSON © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE US NAVY PANTHERS STRIKE EARLY 6 CHAPTER TWO THE WAR DRAGS ON 18 CHAPTER THREE MORE MISSIONS AND MORE MiGS 50 CHAPTER FOUR INTERDICTION, RESCAP, CAS AND MORE MiGS 60 CHAPTER FIVE MARINE PANTHERS ENTER THE WAR 72 APPENDICES 87 COLOUR PLATES COMMENTARY 89 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US NAVY PANTHERS CHAPTER ONE STRIKE EARLY he United States’ brief period of post-World War 2 peace T and economic recovery was abruptly shattered on the morning of 25 June 1950 when troops from the communist state of North Korea crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded their neighbour to the south. American military power in the Far East had by then been reduced to a token force that was ill equipped to oppose the Soviet-backed North Korean military. The United States Air Force (USAF), which had been in the process of moving to an all-jet force in the region, responded immediately with what it had in Japan and Okinawa. The biggest problem for the USAF, however, was that its F-80 Shooting Star fighter-bombers lacked the range to hit North Korean targets, and their loiter time over enemy columns already in South Korea was severely restricted. This pointed to the need for the US Navy to bolster American air power in the region by deploying its aircraft carriers to the region. -

Final Page 1.Indd

Student gleans Dual-sporter Cross country political pointers Porter eager to laps opponents from Obama lead at All-Ohio Page 3 Page 10 Page 12 The Oldest Continuously Published Student Newspaper in the Nation Thursday, October 11, 2007 Volume 146, No. 5 Evan Corns’ Phi Delt rocks out with DropShift donation adds to OWU legacy By Miranda Simmons Editor-in-chief Over 20 years ago, former director of development Ron Stephany (’66) made a phone call that would change the appearance of Ohio Wesleyan forever; he called Evan Corns (’59) and asked him to lunch. Stephany said he knew about Corns and his interest in and loyalty to Ohio Wesleyan, so it was with hope that he drove to Cleveland for the meeting. “I asked him (Corns) if he would consider doing three things,” Stephany said. “First I asked him to serve as a member of Associates, and he agreed.” (Associates is a voluntary board that assists Alumni Relations with fundraising campaigns.) Stephany said he also asked Corns to chair the gift committee for his (Corns’) class reunion that year and to consider giving a $5,000 gift for his reunion. He consented to both. “As we left the restaurant, he put his arm around my shoulder and said, ‘Well, Ron, you’ve had a pretty good day, haven’t you?’” said Stephany. “And I had.” On Oct. 4, Corns gave OWU another good day as he donated $3.25 million dollars in a contribution themed “Today, Tomorrow, and Forever.” As the title suggests, Corns’ donation comes in three parts. -

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NEW VANGUARD 211 US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 ORIGINS OF THE CARRIER AND THE SUPERCARRIER 5 t World War II Carriers t Post-World War II Carrier Developments t United States (CVA-58) THE FORRESTAL CLASS 11 FORRESTAL AS BUILT 14 t Carrier Structures t The Flight Deck and Hangar Bay t Launch and Recovery Operations t Stores t Defensive Systems t Electronic Systems and Radar t Propulsion THE FORRESTAL CARRIERS 20 t USS Forrestal (CVA-59) t USS Saratoga (CVA-60) t USS Ranger (CVA-61) t USS Independence (CVA-62) THE KITTY HAWK CLASS 26 t Major Differences from the Forrestal Class t Defensive Armament t Dimensions and Displacement t Propulsion t Electronics and Radars t USS America, CVA-66 – Improved Kitty Hawk t USS John F. Kennedy, CVA-67 – A Singular Class THE KITTY HAWK AND JOHN F. KENNEDY CARRIERS 34 t USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) t USS Constellation (CVA-64) t USS America (CVA-66) t USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67) THE ENTERPRISE CLASS 40 t Propulsion t Stores t Flight Deck and Island t Defensive Armament t USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 INDEX 48 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS FORRESTAL, KITTY HAWK AND ENTERPRISE CLASSES INTRODUCTION The Forrestal-class aircraft carriers were the world’s first true supercarriers and served in the United States Navy for the majority of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union. -

Saipan Tribune Page 2 of 2

Saipan Tribune Page 2 of 2 ,,," '."..,..US,." .Y """I,"', "...I,, -.-.A I., .I," -I...", .Y. ..,",. .'U""'J, I IYI""IIIIY."~I justified. The area is said to have vegetation and a small pond. The Navy's land use request was coursed through the Office of the Veterans Affairs. Story by Liberty Dones Contact this reporter http://www.saipantribune.com/newsstory.aspx?cat=l&newsID=27904 4/29/03 Marianas Variety On-Line Edition Page 1 of 1 Community biiilcls ties with sailors (DCCA) - Saipan’s reputation as a port of call for U.S. Navy ships is receiving a big boost thanks to a new program that’s building personal ties between island families and sailors. Under its new Sponsor-A-Service Member program, the Department of Community and Cultural Affairs put 18 visiting sailors from the USS Antietam in touch with a local family who voluntarily hosted them while the ship was in Saipan earlier this month. “I want to thank... everyone on your island paradise for making our visit ...on Saipan the best Port Call I’ve ever had - ever!” said Lt. Cmdr. Timothy White, ship chaplain. “Your kindness and hospitality were like nothing we had ever experienced before.” Mite and other sailors were welcomed into the home of Noel and Rita Chargualaf, the first of Saipan residents to sign up for the program. “Every single man who participated has just raved about the wonderful time they had with the families,” said White. “You truly live in an island paradise and the people on your island are the nicest folks I have ever met.” “For the most, they were just thrilled to be around children and families. -

Battle-Of-Waynesboro

Battlefield Waynesboro Driving Tour AREA AT WAR The Battle of Waynesboro Campaign Timeline 1864-1865: Jubal Early’s Last Stand Sheridan’s Road The dramatic Union victory at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, had effectively ended to Petersburg Confederate control in the Valley. Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early “occasionally came up to the front and Winchester barked, but there was no more bite in him,” as one Yankee put it. Early attempted a last offensive in mid- October 19, 1864 November 1864, but his weakened cavalry was defeated by Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s cavalry at Kernstown Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan Newtown (Stephens City) and Ninevah, forcing Early to withdraw. The Union cavalry now so defeats Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early at Cedar Creek. overpowered his own that Early could no longer maneuver offensively. A Union reconnaissance Strasburg Front Royal was repulsed at Rude’s Hill on November 22, and a second Union cavalry raid was turned mid-November 1864 back at Lacey Spring on December 21, ending active operations for the winter season. Early’s weakened cavalry The winter was disastrous for the Confederate army, which was no longer able is defeated in skirmishes at to sustain itself on the produce of the Valley, which had been devastated by Newtown and Ninevah. the destruction of “The Burning.” Rebel cavalry and infantry were returned November 22, to Lee’s army at Petersburg or dispersed to feed and forage for themselves. 1864 Union cavalry repulsed in a small action at Rude’s Hill. Prelude to Battle Harrisonburg December 21, McDowell 1864 As the winter waned and spring approached, Confederates defeat Federals the Federals began to move. -

08-09-14 Draft Planning and Payments Minutes

Planning and Payments ! 8th September 2014 Blackwater and Hawley Town Council Council Offices, Blackwater Centre, 12-14 London Road, Blackwater, Hampshire GU17 9AA Tel: (01276) 33050 [email protected] ! www.blackwaterandhawleytowncouncil.gov.uk Minutes of the Meeting of the Planning and Payments Committee At the Hawley Memorial Hall, Hawley Green Monday! 8th September 2014 at 7pm In Attendance Cllr Hennell (chair planning and payments), Cllr Clarke, Cllr Smith, Cllr Collett, * Cllr Blewett and Mr Gahagan executive officer. Over one hundred members of the public. P&P4222 Apologies Cllrs Hayward, Thames and Keene P&P4223 Councillors’ Declarations of Pecuniary Interests (DPI’s) and/or Councillors’ Dispensations There were no pecuniary interests declared by councillors or dispensations to be considered at the meeting P&P4224 Report of the Chair of the Planning and Payments Committee The committee agreed to take the planning application item 8. A. 3. 14/01817/MAJ. Land to North of Fernhill Lane next, after the democratic fifteen minute agenda item. Cllr Hennell then informed the meeting that she had asked Cllr Collett to chair the meeting because of his knowledge of this application and this was agreed. Cllr Collett then chaired the meeting for this agenda item. P&P4225 Democratic Fifteen Minutes The overwhelming majority of the public in attendance were from the Rushmoor Council area. It was agreed to allow members of the public, the vast majority of which lived outside the parish, to have their say and it was further agreed to extend the democratic fifteen minute agenda item to allow for this. *7.07pm Cllr Blewett arrived at the meeting. -

Braintree District Protected Lanes Assessments July 2013

BRAINTREE DISTRICT PROTECTED LANES ASSESSMENTS July 2013 1 Braintree District Protected Lanes Assessment July 2013 2 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 5 2 Background ............................................................................................... 5 2.1 Historic Lanes in Essex ..................................................................... 5 2.2 Protected Lanes Policy in Essex ....................................................... 6 2.3 Protected Lanes Policy in Braintree District Council .......................... 7 3 Reason for the project .............................................................................. 7 4 Protected Lanes Assessment Procedure Criteria and Scoring System .... 9 4.1 Units of Assessment .......................................................................... 9 4.2 Field Assessment ............................................................................ 10 4.2.1 Photographic Record ................................................................ 10 4.2.2 Data Fields: .............................................................................. 10 4.2.3 Diversity .................................................................................... 11 4.2.4 Historic Integrity ........................................................................ 15 4.2.5 Archaeological Potential ........................................................... 17 4.2.6 Aesthetic Value........................................................................ -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 2 Ohio Adjutant General’s Department / Ohio National Guard Annual Report FY 2016 Since our founding 228 years ago, the Ohio National Guard has been a leader in serving our communities, our state and our nation. We celebrated significant achievements in the past 12 months, made possible by the efforts of the combined full-time and traditional work force of more than 16,000 well-trained, professional Soldiers, Airmen and civilians. Eight out of the 10 Ohio Air National Guard units earned Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards and the Ohio Army National Guard sustained the highest level of readiness in the nation, all while meeting the demands to deploy more than 1,600 Airmen and Soldiers to all points of the globe and performing the 24/7 Aerospace Control Alert mission to protect the homeland. Much of our mission is focused here at home. Support from our counterdrug analysts contributed to more than $6.4 million in illegal drug and drug-related seizures in Ohio. Our medical personnel provided free health care services to residents in Williams County, continuing a nearly 20-year partnership with the Ohio Department of Health that has helped more than 10,000 Ohioans. Collaborating with the Ohio State Highway Patrol, our Soldiers and Airmen talked with more than 30,000 middle and high school students about making healthy, drug-free choices through Ohio’s Start Talking efforts. We also helped our neighbors throughout the year by donating to food pantries, participating in parades and giving blood. I look forward to the next year and prospects for an expanded role for the Ohio National Guard in defending our homeland, as we are being considered for a new national missile defense location at Camp Ravenna and an F-35A joint strike fighter base in Toledo, both of which hold enormous strategic and economic potential for our state. -

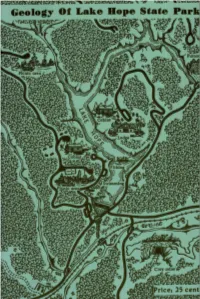

Download the Geology Guide

STATE OF OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RALPH J. BERNHAGEN, CHIEF INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 13 THE GEOLOGY OF LAKE HOPE STATE PARK by MILDRED FISHER MARPLE This publication is a cooperative project of the Division of Parks and Division of Geological Survey Columbus 1954 Reprinted 1996 without revision Price 25 cents c.:i Fronti.spiece. The dam and swimming area as seen from the hill. The strip mine in the Clarion clay is across Raccoon Creek valley on the left. The road in the center is Route 278, at the level of the pre-glacial Zaleski Creek. The heavy sandstone exposed along the spillway at the right i.s the Clarion sandstone. CONTENTS PAGE THE LAKE Location, origin, and setting . 7 THE ROCKS The story told by rock layers . 8 THE MINERAL WEALTH Flint . 9 Iron . 14 Clay . 17 Coal . .. • 18 Sandstone . 21 Oil and gas . 23 THE HILLS The Plateau . 23 The Peneplains . 23 THE RIVERS Before the Ice Age . 26 THE GLACIERS Refrigeration 27 Drainage changes .............. , . 28 6 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Cover, Birdseye view of Lake Hope Frontispiece, Dam and swimming area . 3 Figure 1. Map of southeastern Ohio showing location of Lake Hope State Park . 7 Figure 2. Geologic time chart . 9 Figure 3. Columnar section of rocks in the park . 10 Figure 4. Geologic cross section of the park region . 11 Figure 5. Moundbuilder earthwork at Zaleski . 11 Figure 6. Buhrstone made of flinty Vanport limestone . 12 Figure 7. Hope Furnace . 13 Figure 8. Hecla Furnace . 14 Figure 9. View from the site of "Zaleski Castle" . -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

Liss Walk 9 Web.Ppp

C Cross the road and take the signed footpath at the fields and The Flying Bull PH continue along the track with the fishing lakes on your left to a road. straddles the county Turn left on the lane and after 300 metres turn right and walk uphill boundary with part of the along Primrose Lane (a steep lane through woodland). The lane bar in Hampshire and the finally joins the B2070. Turn left and walk down the hill to the Flying remainder in West Sussex. Bull PH. B C As a shorter alternative, walk up the hill to the village stores, cross the B2070 and take the signed footpath downhill to join the Sussex Border Path. D A D Cross the the B2070 into the lane directly opposite the pub, and Good views across the after 150 metres turn right into Sandy Lane which becomes a footpath valley to the South Downs. at its far end. This is the Sussex Border Path which is followed through woodland for about 2.5 km to a road. As an alternative just before reaching the road, keep walking on the path up through the woodland including a steep climb skirting the treatment works, and turning left down to the road. At this junction turn right and turn right at the next T junction continuing to the Jolly Drover PH. E © Crown copyright and database rights 2012 Ordnance Survey Licence number 100052440 The grid squares are 1km A From the station There is a separate B At the end of the field cross In 1927 turn right over the level information sheet the road and walk down Mint William crossing and then right on the Riverside Road for 500 metres, halfway Pullen again onto the Railway Walk down there is a stream on the started the Riverside Railway Walk nature reserve and left. -

USS Antietam (CV 36) 15 Oct-16 Nov 1951, Part 1

., .. U.S. S. j,'1'l'!ET.. "J1 ( CV-36) c/o Fleet Post Office San Francisco, California CV36;iQ Al6-13 Ser: ~:6~\ 17 November 1951 CC>r:1FIDEFTIA1}' · SECURITY ll~FOPJiATION From: Cor.mJa.nding Officer, U.S.S. ANTIETAlf (CV-36) To: Chief of Naval Operations Via: (1) Cor.ll-na.nder Carrier Division ONE (2) Co!Th-nan ~er Task Force SEVEHTY SEVE:T (3) Conunander s~·TF Fleet (4) Commander :laval Forces, FAR :s;;.ST (5) Co~~nder-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet Subj: Action Report for the period 15 October tbrou:;h 16 November 1951 Hef: (a) OpUav Instruction 3480.4 dtd 1 July 1951 Encl: (1) Conunarder Carrj er l\ir Group FITI.'EE.:~ 1 tr of 17 November 1951 f (~~ ' 1. The Action Report for tre period 15 October 1951 throttgh 16 November 1951 is hereby submitted in accordance ,,nth re:'erence (a). The U. ~. S. "l.?TIET"'J'T arrived at Yokosuka, Japan at 1400! on 4 October 1951. The period 4 - 11 October was spent at anchor in Yoko suka F.arbor and was devoted to voyage reoairs, restricte~. availabj.1ity, and conferences with personnel fro!'l the U.S.S. BOXER (CV-21). ·•t 10001 on 11 October 1951 the u.. s.s. A!~'lTST"\11 cot underway for tbe operating area to join Task Force S:SV:.:'TY SEVEN. in accordance with C'lF-77 Confidentio.l c'ispatch 082216Z. The U.E'>.S. SFELTOH (!}D-790) nccompe.nied the ship in order that refresher air operations could be conducted enroute.