Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’S Civil War Battlefields

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields State of Maryland Washington, DC January 2010 Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields State of Maryland U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Washington, DC January 2010 Authority The American Battlefield Protection Program Act of 1996, as amended by the Civil War Battlefield Preservation Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-359, 111 Stat. 3016, 17 December 2002), directs the Secretary of the Interior to update the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission (CWSAC) Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields. Acknowledgments NPS Project Team Paul Hawke, Project Leader; Kathleen Madigan, Survey Coordinator; Tanya Gossett and January Ruck, Reporting; Matthew Borders, Historian; Kristie Kendall, Program Assistant. Battlefield Surveyor(s) Lisa Rupple, American Battlefield Protection Program Respondents Ted Alexander and John Howard, Antietam National Battlefield; C. Casey Reese and Pamela Underhill, Appalachian National Scenic Trail; Susan Frye, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park; Kathy Robertson, Civil War Preservation Trust; John Nelson, Hager House Museum; Joy Beasley, Cathy Beeler, Todd Stanton, and Susan Trail, Monocacy National Battlefield; Robert Bailey and Al Preston, South Mountain Battlefield State Park. Cover: View of the sunken -

Md Cracker Barrel 2005.Pdf

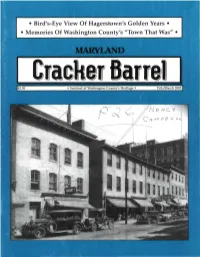

• Bird's-Eye View Of Hagerstown's Golden Years • • Memories Of Washington County's "Town That Was" • MARYLAND l$2.50 • Sentinel of Washington County's Heritage • Feb./March 2005 P oi C> H n H c V Meet Us at the Friendly MARYLAND Cracker Barrel Bi-Monthly! Gather around the pot-bellied stove Grader Bar rel and the checkerboard with a barrel of Our 33rd year common crackers within easy reach and Volume 33 -- No. 4 enjoy the Maryland Cracker Barrel. Since June of 1971 this magazine has Published bi-monthly by been a gathering place for folks interested MARYLAND CRACKER in preserving the heritage of Washington BARREL, INC. 7749 Fairplay Road County. Boonsboro, MD 21713-2322 It is our goal to present the story of the (301)582-3885 individuals who have striven to give this region a heritage worthy of preservation. Editor and Publisher Frank Woodring Associate Editor Suanne Woodring Attention: Former Fairchild Employees Chad Woodring This summer we plan to focus on Fairchild Aircraft in Washing Donald Dayhoff ton County. We would appreciate if you would submit your fa Janet Dayhoff vorite memory of your association with Fairchild by June 1. Fred Kuhn Please include your name, address, department, and number of Bonnie Kuhn years spent with Fairchild. Bob Waring Betty Waring Contributing Writers Coming Richard Clem Jessie Robinette Spring of 2005 Blair Williamson Order Prior to March 1 Printed by to Receive Oak Printing, Inc. Pre-Publication Special 952 Frederick Street Hagerstown, MD 21740 $19.99 (Includes Tax and Shipping) Subscription Rate: $13.65 per year Orders Received Maryland Cracker Barrel After March 1 7749 Fairplay Road $22.99 Boonsboro, MD 21713 301-582-3885 Maryland Cracker Barrel 7749 Fairplay Road [email protected] Boonsboro, MD 21713 Images of America 301-582-3885 FRONT COVER: The photo PEN MAR depicts the east side of the first Images of America, PEN MAR contains 128 pages with more than block of North Potomac Street 200 pictures of historic Pen Mar Park along with the Western in Hagerstown. -

Attorney General's 2013 Chesapeake Bay

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER ONE: LIBERTY AND PRETTYBOY RESERVOIRS ......................................................... 5 I. Background ...................................................................................................................................... 5 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ........................................................................... 8 III. The Liberty Reservoir and Prettyboy Reservoir Audit, May 29, 2013: What the Attorney General Learned .............................................................................................. 11 CHAPTER TWO: THE WICOMICO RIVER ........................................................................................ 14 I. Background .................................................................................................................................... 14 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ..................................................................................... 16 III. The Wicomico River Audit, July 15, 2013: What the Attorney General Learned ......................... 18 CHAPTER THREE: ANTIETAM CREEK ............................................................................................ 22 I. Background .................................................................................................................................... 22 II. Active -

Winter Lights & Lore Media

Media Kit Table of Contents About the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area ................................................................................. 3 About this Media Kit ......................................................................................................................... 4 Winter Lights & Lore: Selected Events ............................................................................................... 5 Memorial Illumination ................................................................................................................................5 Newcomer House Illumination ...................................................................................................................5 Captain Flagg’s US Quartermaster City, 1864: Prospects of Peace ................................................................5 Civil War Christmas in Shepherdstown ........................................................................................................6 Battle of Shepherdstown Illumination .........................................................................................................6 Civil War Encampment ...............................................................................................................................7 Traditional Village Christmas ......................................................................................................................7 While Visions of Sugar Plums Danced in Their Heads ...................................................................................7 -

America's Natural Nuclear Bunkers

America’s Natural Nuclear Bunkers 1 America’s Natural Nuclear Bunkers Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 10 Alabama .............................................................................................................. 12 Alabama Caves .................................................................................................. 13 Alabama Mines ................................................................................................. 16 Alabama Tunnels .............................................................................................. 16 Alaska ................................................................................................................. 18 Alaska Caves ..................................................................................................... 19 Alaska Mines ............................................................................................... 19 Arizona ............................................................................................................... 24 Arizona Caves ................................................................................................... 25 Arizona Mines ................................................................................................... 26 Arkansas ............................................................................................................ 28 Arkansas Caves ................................................................................................ -

March 7,20 12 the Honorable Beverley K. Swaim-Staley, Secretary State of Maryland, Department of Transportation 7201 Corporate C

- \ BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF WASHINGTON COUNTY, MARYLAND Terry L. Baker, Pi-esiderit Washington County Administration Building John F. Barr, Vice-Pwsiu’enr 100 West Washington Street, Room 226 Ruth Anne Callaham Hagerstown, Maryland 21 740-4735 Telephone: 240-313-2200 Jeffrey A. Cline FAX: 240-313-2201 William B. McKinley Deaf and Hard of Hearing call 7-1-1 for Maryland Relay March 7,2012 The Honorable Beverley K. Swaim-Staley, Secretary State of Maryland, Department of Transportation 7201 Corporate Center Drive Hanover, MD 21076 Ref: Board of County Commissioners Transportation Priorities Washington County, Maryland Dear Secretary Swaim-Staley: I am pleased to submit to you the list of transportation priorities in response to correspondence from your Office of Planning and Capital Programming dated December 28, 201 1. The Board of County Commissioners discussed their priorities at their regular meeting held on February 28,2012. They are summarized as follows: 1. Eastern Boulevard Corridor Improvements: This multi-phase project consists of an integrated multi-modal transportation system connecting U.S. Route 40, Maryland Route 64, and Maryland Route 60. Phases I and I1 entails the widening of the existing Eastern Boulevard; Phase I11 involves an extension of Eastern Boulevard to Maryland Route 60. Additional phases include an integration of separate diverse routes to disperse traffic thus reducing traffic volumes on state routes and the return of existing state intersections back to acceptable traffic operational levels of service. These diverse routes include the construction of Professional Court Extended and Yale Drive providing accessibility to critical attractions such as the Regional Meritus Medical facility and Hagerstown Community College and Southern Boulevard near the Town of Funkstown. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Newcomer

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2012 Newcomer Farmstead Antietam National Battlefield Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Newcomer Farmstead Antietam National Battlefield Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI) is an evaluated inventory of all significant landscapes in units of the national park system in which the National Park Service has, or plans to acquire any enforceable legal interest. Landscapes documented through the CLI are those that individually meet criteria set forth in the National Register of Historic Places such as historic sites, historic designed landscapes, and historic vernacular landscapes or those that are contributing elements of properties that meet the criteria. In addition, landscapes that are managed as cultural resources because of law, policy, or decisions reached through the park planning process even though they do not meet the National Register criteria, are also included in the CLI. The CLI serves three major purposes. First, it provides the means to describe cultural landscapes on an individual or collective basis at the park, regional, or service-wide level. Secondly, it provides a platform to share information about cultural landscapes across programmatic areas and concerns and to integrate related data about these resources into park management. Thirdly, it provides an analytical tool to judge accomplishment and accountability. The legislative, regulatory, and policy direction for conducting the CLI include: National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (16 USC 470h-2(a)(1)). -

WA-II-1145 Keedysville Historic District

WA-II-1145 Keedysville Historic District Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-12-2004 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct.1990) United States Department of the Interior -1tional Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. -

Porch Program” Series to Begin at Newcomer House in April

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: March 29, 2016 Contact: Rachel Nichols, Newcomer House Manager: [email protected] Web: www.heartofthecivilwar.org New “Porch Program” Series to Begin at Newcomer House in April Keedysville, MD – The Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area (HCWHA) will begin a new series of monthly public programs at the Newcomer House, HCWHA’s Exhibit & Visitor Center at Antietam National Battlefield, in April. These programs will be free and family-friendly, taking place on the porch of the historic house if weather permits. The first three programs of the 2016 season will cover diverse topics including music of the Civil War era, the role of women at Antietam, and fostering a love for history across generations. Programs taking place July-December are currently under development. April 23: Songs and Stories of the Civil War (11:00 AM, 1:30 PM & 4:00 PM) Through period songs, excerpts from actual letters, and anecdotes both humorous and poignant, Matthew Dodd takes listeners back in time to feel what it was like to be a soldier, civilian, loved-one-at-home or escaped slave in the Civil War era. Dodd will bypass the stories of the generals and the battle movements and concentrate on the feelings of individuals on the home front and seeking freedom. Dodd will play acoustic guitar, harmonica, banjo and mandolin in an informal, story circle setting. May 7: Women of Antietam (11:30 AM and 1:30 PM) Civil War medicine expert Betsy Estilow will discuss the role of nurses and other women at the September 1862 Battle of Antietam on the porch of the Newcomer House. -

BOARD of COUNTY COMMISSIONERS October 8, 2019 OPEN SESSION AGENDA 08:00 A.M. MOMENT of SILENCE and PLEDGE of ALLEGIANCE CALL TO

Wayne K. Keefer Jeffrey A. Cline, President Cort F. Meinelschmidt Terry L. Baker, Vice President Randall E. Wagner Krista L. Hart, Clerk 100 West Washington Street, Suite 1101 | Hagerstown, MD 21740-4735 | P: 240.313.2200 | F: 240.313.2201 WWW.WASHCO-MD.NET BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS October 8, 2019 OPEN SESSION AGENDA 08:00 A.M. MOMENT OF SILENCE AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE CALL TO ORDER, President Jeffrey A. Cline APPROVAL OF MINUTES – September 24, 2019 08:05 A.M. CLOSED SESSION (To discuss the appointment, employment, assignment, promotion, discipline, demotion, compensation, removal, resignation, or performance evaluation of appointees, employees, or officials over whom this public body has jurisdiction; or any other personnel matter that affects one or more specific individuals; To consider the acquisition of real property for a public purpose and matters directly related thereto; To consider a matter that concerns the proposal for a business or industrial organization to locate, expand, or remain in the State; To consult with counsel to obtain legal advice on a legal matter; & To consult with staff, consultants, or other individuals about pending or potential litigation; To discuss public security, if the public body determines that public discussion would constitute a risk to the public or to public security, including: (i) the development of fire and police services and staff; and (ii) the development and implementation of emergency plans.) 10:00 A.M. RECONVENE IN OPEN SESSION 10:05 A.M. COMMISSIONERS’ REPORTS AND COMMENTS 10:15 A.M. REPORTS FROM COUNTY STAFF 10:25 A.M. CITIZENS PARTICIPATION 10:30 A.M. -

WA-II-703 Piper House

WA-II-703 Piper House Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-12-2004 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service _.ATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A) . Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. -

SHEPHERDSTOWN BATTLEFIELD Special Resource Study / Boundary Study / National Park Service U.S

SHEPHERDSTOWN BATTLEFIELD SPECIAL RESOURCE STUDY / BOUNDARY STUDY / National Park Service ENVIRONMENTAL AssEssMENT U.S. Department of the Interior WEST VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND August 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior Shepherdstown Battlefield West Virginia and Maryland August 2014 Special Resource Study / Boundary Study / Environmental Assessment HOW TO COMMENT ON THIS STUDY Comments are welcome and will be accepted for a HAND DELIVERY: minimum of 30 days after this study is published and distributed. While comments may be submitted by any one Written and/or verbal comments may be made at public of the following methods commenters are encouraged to meetings. The dates, times, and locations of public use the Internet, if possible. meetings will be announced in the media and on the Planning, Environment, and Public Comment site (Web MAIL: address above) following release of this document. National Park Service Please submit only one set of comments. Denver Service Center – Planning Jordan Hoaglund, Project Manager Before including your address, telephone number, e-mail PO Box 25287 address, or other personal information in your comment, Denver, CO 80225-0287 you should be aware that your entire comment—including your personal identifying information—may be made ONLINE: publicly available at any time. Although you can ask us http://parkplanning.nps.gov/shba in your comment to withhold your personal identifying information from public review, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to do so. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION The Department of the Interior, National Park Service study criteria to evaluate the suitability and feasibility (NPS), has prepared this special resource study / boundary of the addition.