Attorney General's 2013 Chesapeake Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Branch Patapsco River Watershed Characterization Plan

South Branch Patapsco River Watershed Characterization Plan Spring 2016 Prepared by Carroll County Bureau of Resource Management South Branch Patapsco Watershed Characterization Plan Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iv List of Appendices .......................................................................................................................... v List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... vi I. Characterization Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 A. Purpose of the Characterization ....................................................................................... 1 B. Location and Scale of Analysis ........................................................................................ 1 C. Report Organization ......................................................................................................... 3 II. Natural Characteristics ............................................................................................................ 5 A. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

News Release Address: Email and Homepage: U.S

News Release Address: Email and Homepage: U.S. Department of the Interior Maryland-Delaware-D.C. District [email protected] U.S. Geological Survey 8987 Yellow Brick Road http://md.water.usgs.gov/ Baltimore, MD 21237 Release: Contact: Phone: Fax: January 4, 2002 Wendy S. McPherson (410) 238-4255 (410) 238-4210 Below Normal Rainfall and Warm Temperatures Lead to Record Low Water Levels in December Three months of above normal temperatures and four months of below normal rainfall have led to record low monthly streamflow and ground-water levels, according to hydrologists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Baltimore, Maryland. Streamflow was below normal at 94 percent of the real-time USGS gaging stations and 83 percent of the USGS observation wells across Maryland and Delaware in December. Record low streamflow levels for December were set at Winters Run and Pocomoke River. Streamflow levels at Deer Creek and Winters Run in Harford County have frequently set new record daily lows for the last four months (see real-time graphs at http://md.water.usgs.gov/realtime/). Streamflow was also significantly below normal at Antietam Creek, Choptank River, Conococheague Creek, Nassawango Creek, Patapsco River, Gunpowder River, Patuxent River, Piscataway Creek, Monocacy River, and Potomac River in Maryland, and Christina River, St. Jones River, and White Clay Creek in Delaware. The monthly streamflow in the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. was 82 percent below normal in December and 54 percent below normal for 2001. Streamflow entering the Chesapeake Bay averaged 23.7 bgd (billion gallons per day), which is 54 percent below the long-term average for December. -

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’S Civil War Battlefields

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields State of Maryland Washington, DC January 2010 Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields State of Maryland U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Washington, DC January 2010 Authority The American Battlefield Protection Program Act of 1996, as amended by the Civil War Battlefield Preservation Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-359, 111 Stat. 3016, 17 December 2002), directs the Secretary of the Interior to update the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission (CWSAC) Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields. Acknowledgments NPS Project Team Paul Hawke, Project Leader; Kathleen Madigan, Survey Coordinator; Tanya Gossett and January Ruck, Reporting; Matthew Borders, Historian; Kristie Kendall, Program Assistant. Battlefield Surveyor(s) Lisa Rupple, American Battlefield Protection Program Respondents Ted Alexander and John Howard, Antietam National Battlefield; C. Casey Reese and Pamela Underhill, Appalachian National Scenic Trail; Susan Frye, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park; Kathy Robertson, Civil War Preservation Trust; John Nelson, Hager House Museum; Joy Beasley, Cathy Beeler, Todd Stanton, and Susan Trail, Monocacy National Battlefield; Robert Bailey and Al Preston, South Mountain Battlefield State Park. Cover: View of the sunken -

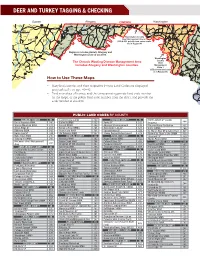

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Garrett Allegany CWDMA Washington Frederick Carroll Baltimore Harford Lineboro Maryland Line Cardiff Finzel 47 Ellerlise Pen Mar Norrisville 24 Whiteford ysers 669 40 Ringgold Harney Freeland 165 Asher Youghiogheny 40 Ke 40 ALT Piney Groev ALT 68 615 81 11 Emmitsburg 86 ge Grantsville Barrellville 220 Creek Fairview 494 Cearfoss 136 136 Glade River aLke Rid 546 Mt. avSage Flintstone 40 Cascade Sabillasville 624 Prospect 68 ALT 36 itts 231 40 Hancock 57 418 Melrose 439 Harkins Corriganville v Harvey 144 194 Eklo Pylesville 623 E Aleias Bentley Selbysport 40 36 tone Maugansville 550 419410 Silver Run 45 68 Pratt 68 Mills 60 Leitersburg Deep Run Middletown Springs 23 42 68 64 270 496 Millers Shane 646 Zilhman 40 251 Fountain Head Lantz Drybranch 543 230 ALT Exline P 58 62 Prettyboy Friendsville 638 40 o 70 St. aulsP Union Mills Bachman Street t Clear 63 491 Manchester Dublin 40 o Church mithsburg Taneytown Mills Resevoir 1 Aviltn o Eckhart Mines Cumberland Rush m Spring W ilson S Motters 310 165 210 LaVale a Indian 15 97 Rayville 83 440 Frostburg Glarysville 233 c HagerstownChewsville 30 er Springs Cavetown n R 40 70 Huyett Parkton Shawsville Federal r Cre Ady Darlingto iv 219 New Little 250 iv Cedar 76 140 Dee ek R Ridgeley Twiggtown e 68 64 311 Hill Germany 40 Orleans r Pinesburg Keysville Mt. leasP ant Rocks 161 68 Lawn 77 Greenmont 25 Blackhorse 55 White Hall Elder Accident Midlothian Potomac 51 Pumkin Big pringS Thurmont 194 23 Center 56 11 27 Weisburg Jarrettsville 136 495 936 Vale Park Washington -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Trip Schedule NOVEMBER 2013 – FEBRUARY 2014 the Club Is Dependent Upon the Voluntary Trail Policies and Etiquette Cooperation of Those Participating in Its Activities

Mountain Club of Maryland Trip Schedule NOVEMBER 2013 – FEBRUARY 2014 The Club is dependent upon the voluntary Trail Policies and Etiquette cooperation of those participating in its activities. Observance of the following guidelines will enhance the enjoyment The Mountain Club of Maryland (MCM) is a non-profit organization, of everyone: founded in 1934, whose primary concern is to provide its members and • Register before the deadline. Early registration for overnight or com- guests the opportunity to enjoy nature through hiking and other activi- plicated trips is especially helpful. Leaders may close registration early ties, particularly in the mountainous areas accessible to Baltimore. when necessary to limit the size of the trip. The leader may also refuse We publish a hike and activities schedule, with varieties in location registration to persons who may not be sufficiently strong to stay with and difficulty. We welcome guests to participate in most of our activi- the group. ties. We include some specialized hikes, such as family or nature hikes. • Trips are seldom canceled, even for inclement weather. Check with We help each other, but ultimately everyone is responsible for their the leader when conditions are questionable. If you must cancel, call individual safety and welfare on MCM trips. the leader before he or she leaves for the starting point. Members and We generally charge a guest fee of $2 for non-members. This fee is guests who cancel after trip arrangements have been made are billed waived for members of other Appalachian Trail maintaining clubs. Club for any food or other expenses incurred. members, through their dues, pay the expenses associated with publish- • Arrive early. -

Freshwater Fisheries Monthly Report – November 2019 Freshwater Fisheries

Freshwater Fisheries Monthly Report – November 2019 Freshwater Fisheries - Stock Assessment Upper Potomac River - Completed the annual fall electrofishing survey of the upper Potomac River. This survey collects information on adult smallmouth bass at multiple sites from Seneca upstream to Paw Paw, WV. Unfortunately, as expected, catch rates for adult smallmouth bass were down compared to the long-term average. Poor juvenile recruitment for the past 10 years has been a major factor behind this decline. Planning efforts are underway to produce juvenile smallmouth bass at hatchery facilities to boost numbers in areas of the river that have experienced the biggest declines. The surveys did show good numbers of juvenile fish produced during the 2019 spring spawn in some sections of the river. This is positive news that the population can bounce back if river flows remain stable during the spawning period. Average catch rate for adult smallmouth bass ( greater than11 inches) in the upper Potomac River (1988-2019). Liberty Reservoir - Conducted a nighttime electrofishing survey on Liberty Reservoir (Baltimore and Carroll counties). Fourteen random sites around the entire perimeter of Liberty Reservoir were surveyed over three nights. Preliminary results show the proportional stock density (PSD) for smallmouth bass was 62 and the catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) of stock size and larger 1 smallmouth bass was 3/hour. Only nine smallmouth bass were collected during the survey. The largest smallmouth bass collected measured 44.9 cm (17.7 inches, 2.7 pounds). The largemouth bass PSD was 56 and the CPUE was 26/hour. The largest largemouth bass collected measured 49.1 cm (19.3 inches, 4.2 pounds). -

Multiproxy Evidence of Holocene Climate Variability from Estuarine Sediments, Eastern North America T

PALEOCEANOGRAPHY, VOL. 20, PA4006, doi:10.1029/2005PA001145, 2005 Multiproxy evidence of Holocene climate variability from estuarine sediments, eastern North America T. M. Cronin,1 R. Thunell,2 G. S. Dwyer,3 C. Saenger,1 M. E. Mann,4,5 C. Vann,1 and R. R. Seal II1 Received 14 February 2005; revised 19 May 2005; accepted 8 July 2005; published 19 October 2005. [1] We reconstructed paleoclimate patterns from oxygen and carbon isotope records from the fossil estuarine benthic foraminifera Elphidium and Mg/Ca ratios from the ostracode Loxoconcha from sediment cores from Chesapeake Bay to examine the Holocene evolution of North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)-type climate variability. Precipitation-driven river discharge and regional temperature variability are the primary influences 18 on Chesapeake Bay salinity and water temperature, respectively. We first calibrated modern d Owater to salinity 18 and applied this relationship to calculate trends in paleosalinity from the d Oforam, correcting for changes in water temperature estimated from ostracode Mg/Ca ratios. The results indicate a much drier early Holocene in which mean paleosalinity was 28 ppt in the northern bay, falling 25% to 20 ppt during the late Holocene. Early Holocene Mg/Ca-derived temperatures varied in a relatively narrow range of 13° to 16°C with a mean temperature of 14.2°C and excursions above 16°C; the late Holocene was on average cooler (mean temperature of 12.8°C). In addition to the large contrast between early and late Holocene regional climate conditions, multidecadal (20–40 years) salinity and temperature variability is an inherent part of the region’s climate during both the early and late Holocene, including the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age. -

Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2011/488 ON THE COVER Potomac River near Paw Paw, West Virginia Photograph by: Tom Paradis, NPS. Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2011/488 John Paul Schmit National Park Service Center for Urban Ecology 4598 MacArthur Blvd. NW Washington, DC 20007 September, 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received formal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data, and whose background and expertise put them on par technically and scientifically with the authors of the information. -

Savage River State Forest Is a Natural Area with Hunting Is Permitted Throughout the Forest

DIRECTIONS Take Exit 22 off I-68, turn left and go south on Chestnut Ridge WELCOME Please Play Safe! HUNTING Savage River Reservoir Road. At the stop sign, turn left onto New Germany Road. Savage River State Forest is a natural area with Hunting is permitted throughout the forest. The Savage River Reservoir provides fishing and Continue for two miles. Turn right onto Headquarters Lane certain hazards such as overhanging branches, Boundaries are marked with yellow paint. No paddling opportunities. Boat launches are located and continue to the forest office on the right. rocky and slippery trails, and venomous hunting allowed where there are safety zone signs or at Big Run State Park, Dry Run Road and near the snakes. Bottles of water and sturdy shoes are where posted by private landowners. Hunters should breast of the dam. No gasoline motors are permitted. Approximately 3 hours from Washington, D.C./Baltimore, 2 hours from Pittsburgh. recommended while exploring, as well as blaze consult the Maryland Hunting Guide — available at Anglers can catch Catfish, Trout, Bass and Tiger orange clothing during hunting seasons. Some of dnr.maryland.gov/huntersguide — for exact season Muskie. Depending on the season, visitors may More information is available at dnr.maryland.gov/ the forest trails are gravel roads, which are open dates and bag limits. see grouse, great blue herons, king fishers, minks publiclands/western/savageriverforest.asp or by contacting to motor vehicles at various times. Remember, and eagles as well. Swimming in the Reservoir is the forest office. you are responsible for having the necessary Several access roads are available to hunters with prohibited. -

2021 Quick Reference

2021 2021 12, Quick Reference August 1. Maintain and improve environmental quality and encourage economic prosperity while preserving the county’s rural character. 2. Promote land use, planning, and development concepts and practices that support citizens’ health, safety, well-being, individual rights and the economic viability of Carroll County. 3. Maintain safe and adequate drinking water and other water supplies including efforts to protect and restore the Chesapeake Bay. 4. Strive to protect our natural resources for future generations. Solar Panel Surface Area Maximum Square Footage for Ground-Mounted Systems in Lot Size Residential Zones <= ½ acre 120 square feet >½ acre 240 square feet >1 acre to 3 acres 480 square feet Aggregate square footage of the roof, or >3 acres roofs of structures, situated on the subject property In May 2021, the Commissioners amended the County Zoning Code to allow community solar energy generating systems (CSEGSs) on remaining portions in the Agricultural Zone. The Code requires a permanent easement on the rest of the property, co-location with agricultural uses or pollinator friendly plantings, and landscaped screening. An outreach booklet provides information on the amendment. The County installed solar arrays on 3 different County properties – Carroll Community College, Hoods Mill Landfill, and Hampstead WWTP – to conserve energy and realize cost savings. These facilities came online in 2018. In 2018, Carroll County received a Silver Designation by the national Fiscal Year # of Permits SolSmart program. 2015 383 2016 606 2017 463 2018 312 2019 194 2020 157 Carroll protected 102 miles of buffered streams under easements. As of December 2020, water recharge areas were protected on 3,599 acres incorporated into 27 easements.