Ohio Motto Survives the Establishment Clause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Page 1.Indd

Student gleans Dual-sporter Cross country political pointers Porter eager to laps opponents from Obama lead at All-Ohio Page 3 Page 10 Page 12 The Oldest Continuously Published Student Newspaper in the Nation Thursday, October 11, 2007 Volume 146, No. 5 Evan Corns’ Phi Delt rocks out with DropShift donation adds to OWU legacy By Miranda Simmons Editor-in-chief Over 20 years ago, former director of development Ron Stephany (’66) made a phone call that would change the appearance of Ohio Wesleyan forever; he called Evan Corns (’59) and asked him to lunch. Stephany said he knew about Corns and his interest in and loyalty to Ohio Wesleyan, so it was with hope that he drove to Cleveland for the meeting. “I asked him (Corns) if he would consider doing three things,” Stephany said. “First I asked him to serve as a member of Associates, and he agreed.” (Associates is a voluntary board that assists Alumni Relations with fundraising campaigns.) Stephany said he also asked Corns to chair the gift committee for his (Corns’) class reunion that year and to consider giving a $5,000 gift for his reunion. He consented to both. “As we left the restaurant, he put his arm around my shoulder and said, ‘Well, Ron, you’ve had a pretty good day, haven’t you?’” said Stephany. “And I had.” On Oct. 4, Corns gave OWU another good day as he donated $3.25 million dollars in a contribution themed “Today, Tomorrow, and Forever.” As the title suggests, Corns’ donation comes in three parts. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 2 Ohio Adjutant General’s Department / Ohio National Guard Annual Report FY 2016 Since our founding 228 years ago, the Ohio National Guard has been a leader in serving our communities, our state and our nation. We celebrated significant achievements in the past 12 months, made possible by the efforts of the combined full-time and traditional work force of more than 16,000 well-trained, professional Soldiers, Airmen and civilians. Eight out of the 10 Ohio Air National Guard units earned Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards and the Ohio Army National Guard sustained the highest level of readiness in the nation, all while meeting the demands to deploy more than 1,600 Airmen and Soldiers to all points of the globe and performing the 24/7 Aerospace Control Alert mission to protect the homeland. Much of our mission is focused here at home. Support from our counterdrug analysts contributed to more than $6.4 million in illegal drug and drug-related seizures in Ohio. Our medical personnel provided free health care services to residents in Williams County, continuing a nearly 20-year partnership with the Ohio Department of Health that has helped more than 10,000 Ohioans. Collaborating with the Ohio State Highway Patrol, our Soldiers and Airmen talked with more than 30,000 middle and high school students about making healthy, drug-free choices through Ohio’s Start Talking efforts. We also helped our neighbors throughout the year by donating to food pantries, participating in parades and giving blood. I look forward to the next year and prospects for an expanded role for the Ohio National Guard in defending our homeland, as we are being considered for a new national missile defense location at Camp Ravenna and an F-35A joint strike fighter base in Toledo, both of which hold enormous strategic and economic potential for our state. -

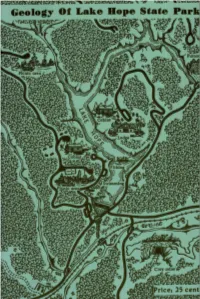

Download the Geology Guide

STATE OF OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RALPH J. BERNHAGEN, CHIEF INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 13 THE GEOLOGY OF LAKE HOPE STATE PARK by MILDRED FISHER MARPLE This publication is a cooperative project of the Division of Parks and Division of Geological Survey Columbus 1954 Reprinted 1996 without revision Price 25 cents c.:i Fronti.spiece. The dam and swimming area as seen from the hill. The strip mine in the Clarion clay is across Raccoon Creek valley on the left. The road in the center is Route 278, at the level of the pre-glacial Zaleski Creek. The heavy sandstone exposed along the spillway at the right i.s the Clarion sandstone. CONTENTS PAGE THE LAKE Location, origin, and setting . 7 THE ROCKS The story told by rock layers . 8 THE MINERAL WEALTH Flint . 9 Iron . 14 Clay . 17 Coal . .. • 18 Sandstone . 21 Oil and gas . 23 THE HILLS The Plateau . 23 The Peneplains . 23 THE RIVERS Before the Ice Age . 26 THE GLACIERS Refrigeration 27 Drainage changes .............. , . 28 6 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Cover, Birdseye view of Lake Hope Frontispiece, Dam and swimming area . 3 Figure 1. Map of southeastern Ohio showing location of Lake Hope State Park . 7 Figure 2. Geologic time chart . 9 Figure 3. Columnar section of rocks in the park . 10 Figure 4. Geologic cross section of the park region . 11 Figure 5. Moundbuilder earthwork at Zaleski . 11 Figure 6. Buhrstone made of flinty Vanport limestone . 12 Figure 7. Hope Furnace . 13 Figure 8. Hecla Furnace . 14 Figure 9. View from the site of "Zaleski Castle" . -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

History of the Great Seal the Great Seal of the State of Ohio Features Ohio’S Coat of Arms Sur‐ Rounded by the Words, "THE GREAT SEAL of the STATE of OHIO"

History of the Great Seal The Great Seal of the State of Ohio features Ohio’s coat of arms sur‐ rounded by the words, "THE GREAT SEAL OF THE STATE OF OHIO". The coat of arms features a full sheaf of wheat, symbolizing agriculture and bounty; a cluster of seventeen arrows, symbolizing Ohio's admittance as the seventeenth state into the Union, Mount Logan, Ross County, as viewed from the Adena Mansion; a rising sun three‐quarters exposed and radiating thirteen rays to represent the original thirteen colonies shining over the first state of the Northwest Territory; and a representation of the Scioto River and cultivated fields. The design is said to have been the cooperative inspiration of Thomas Worthington, "Father of Ohio Statehood;" Edward Tiffin, the first governor; and William Creighton, first secretary of state. The seal was adopted on March 28, 1803, for official use by the governor and has changed at least ten times in the state's history. The Ohio General Assembly adopted the current coat of arms in 1967. Activity Teach Cloverbuds about Ohio’s Great Seal and help them create their own piece of history. This activity utilizes natural ingredients and teaches youth about Ohio’s agricultural heritage. You will need: Dried bean soup mix with a variety of colors Bowls to sort beans Blue acrylic craft paint Sealable plastic bag Waxed paper Tacky glue Blue crayon Tan card stock Spaghetti Raffia Prepared by: Bruce Zimmer, Extension Educator, 4-H Youth Development, OSU Extension Monroe County, Ohio, Buckeye Hills EERA. Instructions 1. This activity could be expanded into two meetings—sorting and gluing. -

Thomas Worthington Father of Ohio Statehood

THOMAS WORTHINGTON FATHER OF OHIO STATEHOOD Thomas Worthington Father of Ohio Statehood BY ALFRED BYRON SEARS Ohio State University Press Columbus Illustration on p. ii courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society. Copyright © 1998 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sears, Alfred Byron, 1900 Thomas Worthington : father of Ohio statehood / by Alfred Byron Sears. p. cm. Originally published : Columbus ; Ohio State University Press for the Ohio Historical Society, [1958] Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-0745-6 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Politicians—Ohio—Biography. 2. Ohio—Politics and government— 1787-1865. I. Worthington, Thomas, 1773-1827. II. Title. F495.W73 1998 977.r03'092—dc21 [B] 97-51221 CIP Cover design by Gore Studio, Inc. Printed by Cushing-Malloy, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 98765432 1 DEDICATED TO JAMES T. WORTHINGTON 1873-1949 ViRTUTE DiGNUS AVORUM PREFACE IN THE movement to secure Ohio's admission to the Union and in the framing of an enlightened and democratic constitution, which excluded slavery, banished executive tyranny, and safeguarded private and pub lic liberties in a comprehensive bill of rights, no one displayed greater leadership than Thomas Worthington. In a very real sense, Ohio is a monument to his memory. Yet his political services have never been adequately recognized, and no biography of him has hitherto appeared. Worthington was a dominant figure in early Ohio politics. -

Along the Ohio Trail (PDF)

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dave Yost • Auditor of State Dear Ohioan, Join your trail guide Simon for a hike through Ohio’s history! As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you’ll learn about what makes our state different from all the others and how we got to where we are today. The first stop on the trail teaches you about Ohio’s geography; some of the things you see every day and what’s in the ground underneath you. Next on our journey, you’ll find out what Ohio was like in pre-his- toric times and about the first people to make the land their home. Simon’s tour continues through a time when Native Americans lived here and when Europeans came to discover the area. Finally, you’ll learn about the process by which Ohio became the 17th state in the Union and the events that made Ohio the place you call home. I hope you enjoy your adventure in discovering the great state of Ohio! Sincerely, Dave Yost Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. -

Anohio Alphabet

60048_Jacket.8:AlphaJacket.temp 8/5/10 3:07 PM Page 1 B is for Buckeye Discover America Marcia Schonberg Discover America state by state with other alphabet books State by State is for Author Marcia Schonberg combines her love of learn- by Sleeping Bear Press COLLECT ALL 51 BOOKS B Buckeye ing, writing, and teaching in her first children’s book, B is for Buckeye: An Ohio Alphabet. Here, her rhymes An Ohio Alphabet and prose introduce young readers to her favorite state. Did you know that Ohio is called “The Mother of A graduate of The Ohio State University and a lifelong Presidents” for the eight United States Presidents “Buckeye,” she is also the author of two travel guides born there? Or that 23 astronauts—the most of any for Ohio and contributes feature stories and photos to rr uucc BB kk state—are from Ohio? These and more amazing facts magazines and daily newspapers. oo ff ee are revealed in B is for Buckeye: An Ohio Alphabet, a yy must-have for every Ohioan (from Ulysses S. Grant Marcia is also an accomplished photographer, taking ss Ohio ii to John Glenn)! photographs for her writing as well as for her fine art ee collection. Her photographs appear in visitor’s guides, Fascinating text by Ohio author Marcia Schonberg posters, postcards, and in galleries. She lives in and stunning illustrations by renowned wildlife artist Lexington, Ohio with her husband Bill and golden Bruce Langton bring Ohio history and information retriever Cassie. BB to life in this book, created for your favorite Buckeye. -

ODNR Division of Watercraft Paddle Sports Report

ODNR Division of Watercraft Paddlesports Report A Summary of Revenue and Expenditures 2004 – 2013 The purpose of this report is to list financial contributions of paddlers (canoeists/kayakers) through their watercraft registration fees, and to show expenditures from the ODNR Division of Watercraft in support of this user group. Information in this report covers 2004 through 2013. Common services not specific to paddlers, such as homeland security, accident investigation, general law enforcement services, general publication printing and development, boater safety education courses, web site maintenance, boating access facilities, boat safety inspections, hull identification inspections, registration records management, as well as administrative services and payroll, are not detailed in this report. The report is presented in three sections: Part I: Registration and Numbering Revenue 2004-2013 Part II: Paddle Sports Program Expenditures 2004-2013 Part III: Additional Statewide Services Provided Exclusively for Paddlers Paddlesports Report 05/2014 ODNR Division of Watercraft 1 of 11 Part I: Registration and Numbering Revenue 2004-2013 Over a ten-year period, paddlesports generated over $4 million in direct revenue through registration fees. This includes fees collected through traditional 3-year registrations, alternative registrations, and livery registrations: 2004 - 2009 Revenue Registration Type 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Canoe/Kayak 50,335 52,098 54,155 59,422 61,064 64,803 Alternative*** 4,533 6,428 8,239 10,857 14,000 17,867 Livery -

Chillicothe the Delphi of North America

CHILLICOTHE THE DELPHI OF NORTH AMERICA Historian Roger Kennedy has aptly called HISTORIC DOWNTOWN Arriving in Ohio’s first capital the “Delphi of North Amer- Chillicothe by US Route 50 (from Bainbridge), ica” no less for its remarkable concentration of brings you directly into downtown on Main Greek Revival architecture than for its status as Street. Its intersection with Paint Street marks the heartland of the brilliant Hopewell culture, the center of 16+ blocks of remarkable historic whose influence was spread across much of the architecture, much dating from the time when continent seventeen centuries ago (see: Mound Chillicothe newspaper editor Ephraim Squier City). The downtown historic district includes and local physician Edwin Davis collaborated restored bed-and-breakfasts from which to plan on their Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi several days’ excursions here in the “Heartland Valley, the first publication of the new Smithso- of Ancient America.” nian Institution, in 1848. The Chillicothe/Ross County Convention The name “Chillicothe” means “principal and Visitors Bureau has offices downtown at town” in Shawnee, and old Ohio maps show 45 Main Street (800-413-4118 http://www.vis- several Shawnee-era “chillicothes.” But it was itchillicotheohio.com) and can provide further this one that, long before, was a major center of information on where to stay and eat, and what Ohio’s earthwork building culture, and that in else to do in the area. 1803 became Ohio’s first state capital. Prosper- ity came early to this village on the banks of the Scioto, a gateway to the large “Virginia Military District” 5 between here and the Little Miami River to the west. -

Ohio Becomes a State Ohio's 1St Constitution Causes of War of 1812 Leading to War of 1812 War of 1812

Ohio Becomes Causes of Leading to Ohio’s 1st War of A War of War of Constitution 1812 State 1812 1812 100 100 100 100 100 200 200 200 200 200 300 300 300 300 300 400 400 400 400 400 500 500 500 500 500 Established by Pres. Jefferson to admit Ohio as a State as soon as possible Enabling Act of 1802 This group led by Arthur St. Clair, wanted to divide Ohio into two States to delay Statehood status to retain some power Federalists A Democratic Republican group that waned to tar and feather St. Clair for his proposed Division Act Bloodhounds was the last step to becoming a State according to the NW Ordinance Submitting a Constitution Democratic Republicans led by Thomas Worthington wanted a central gov’t and more power to the General Assembly Weak The name of Ohio’s State Seal “The Great Seal of Ohio” All power belongs to the… People This position was to hold supreme executive power Governor Ohio’s 1st Const explicitly prohibited this… Slavery The General Assembly was to consist of… Senate and House 1803 British Navy started seizing American ships and American sailors would be forced to serve as British sailors was called… Impressment Name two of the three territories the War Hawks wanted to engage in war to expand US boundaries Florida, Mexico and Canada The Doves or Anti-War group in US Congress were mainly from this region of the US New England This replaced the Embargo Act which opened US trade to all countries except Britain Non-Intercourse Act Treaty signed near Toledo in which the older tribesmen of the Indians will sign away the majority of their remaining territory in the Ohio region Treaty of Fort Industry Town where Tecumseh and brother would base their efforts to push the white man back east Tippecanoe Governor of the Indiana Territory William Henry Harrison The Battle of Tippecanoe was started because the US had received reports that the Indians had received a shipment of goods from who? British Congress will declare war on the British in what year? 1812 Governor of the Michigan Territory and will suffer an embarrassing surrender at Detroit Gen. -

Criminology, Psychology & Sociology Internships

CRIMINOLOGY, PSYCHOLOGY & SOCIOLOGY INTERNSHIPS INTERNSHIP TITLES ORGANIZATIONS LOCATIONS Adaptive Behavioral Specialist St. Vincent Family Centers Columbus, OH Assistant Case Manager Madison County Mental Health Madison County, OH Assistant to Detectives Bexley Police Department Bexley, OH Behavior Technician Applied Behavior Services Columbus, OH Behavioral Health Intern Nationwide Children's Hospital Columbus, OH Behavioral Science Intern Behavioral Science Specialists Columbus, OH Camp Counselor Fernwood Cove (girls camp) Harrison, Maine Camp Counselor Girl Scouts Seal of Ohio Council, Inc. Columbus, OH Case Manager Intern T.O.U.C.H. Columbus, OH Certified Recovery Specialist Alvis House Columbus, OH Clinical Assistant Behavioral Science Specialists Columbus, OH Cognitive Psychology Research University of Toledo Toledo, OH Communications Intern City Year Columbus Columbus, OH Community Corrections Specialist Alvis House Columbus, OH Community Organizers Ohio Citizen Action Columbus, OH Community Organizing Intern ACORN Columbus, OH Community Support Intern St. Vincent Family Centers Columbus, OH Family Violence Prevention Center of Crisis Intervention Program Xenia, OH Greene County Democratic Caucus Page Ohio House of Representatives Columbus, OH The Columbus Foundation/Charitable Development Fellow Columbus, OH Pharmacy of Central Ohio Ohio Attorney General Office Bureau of DNA Laboratory Intern London, OH Criminal Identification and Investigation Education Intern Catholic Social Services Columbus, OH Education Intern Franklin County