Ender's Game Took the Sf World by Storm, Sweeping the Awards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Space Colonialism

Andréu - 1 Lydia I. Andreu Dr. Robert W. Rudnicki ENGL 480 14 November 2013 Beyond Space Colonialism: Otherness in Orson Scott Card’s Speaker for the Dead As a sequel to the much acclaimed Ender’s Game , Speaker for the Dead presents a future where most of humanity’s actions are a result of dealing with the guilt of destroying the only other known intelligent life form in the universe, the “buggers.” Taking place some three thousand years after the events of Ender’s Game , the sequel explores the social implications of Andrew “Ender” Wiggin’s actions, as well as the results of space colonization. The society presented in the novel is composed of “the Hundred Worlds,” planets colonized by humans and bound by “ansible” communication and the laws of the “Starways Congress.” When Portuguese colonizers discover the “pequeninos” or “piggies,” intelligent alien life forms in the newly colonized Lusitania, humanity is given the opportunity to coexist with aliens and make amends for the destruction of the buggers. However, soon the inability of humans to understand the seemingly brutal customs of the pequeninos threatens to trigger another alien war. The discovery of the pequeninos and the resulting relations between them and the humans reflect old colonial anxieties that were present during Euro-American colonization. These anxieties result from the age-old fear of “otherness.” In Speaker for the Dead , otherness not only takes the form of an alien “other,” but Card takes it one step further by exploring different levels of foreignness outside and within a community. Individuals in the novel are not merely foreign or alien because they belong to a different race or community, but because societal barriers intended to protect Andréu - 2 them (and the community) result in the inability to communicate effectively, and thus in foreignness. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

A Science-Fiction Sampler

A Science-Fiction Sampler Matthew Menning The Fox network's popular television drama, "The X-Files," is concerned with the quest of two FBI agents for the truth in the face of the apparently unexplainable. In a recent episode, Agent Scully, the team's skeptic, struggled with terminal cancer. Lying on her hospital bed, she spoke with her partner about her illness. As an adult, she said, she put her faith in science and her desire for truth. When science and logic failed to explain a mystery, she was willing to entertain the possibility of anything from alien contact to government conspiracy. Not until cancer brought her close to death did she reconsider faith in a God who is present in this world and who offers strength to those in need. For Agent Scully, accepting the presence of a God she could not explain and did not understand required more courage than battles with terrorists or alien abduction. Scully risked her objectivity and discovered a peace and potency that enabled her to endure her cancer until she was healed. Agent Scully's dilemma is not unfamiliar. Since the Renaissance, scientists have astounded us with their discoveries. That which was unexplainable has become increasingly mundane. Humans have walked on the moon, come to understand the workings of subatomic particles and discovered the secrets of heating food using microwaves. Most of us do not understand the science behind these marvels, but accept the fact that scientists do, and could explain them to us if we wished to learn. For many of us, it has become increasingly difficult to believe that there is anything science cannot explain, given time and resources . -

Spring 2021 Tor Catalog (PDF)

21S Macm TOR Page 1 of 41 The Blacktongue Thief by Christopher Buehlman Set in a world of goblin wars, stag-sized battle ravens, and assassins who kill with deadly tattoos, Christopher Buehlman's The Blacktongue Thief begins a 'dazzling' (Robin Hobb) fantasy adventure unlike any other. Kinch Na Shannack owes the Takers Guild a small fortune for his education as a thief, which includes (but is not limited to) lock-picking, knife-fighting, wall-scaling, fall-breaking, lie-weaving, trap-making, plus a few small magics. His debt has driven him to lie in wait by the old forest road, planning to rob the next traveler that crosses his path. But today, Kinch Na Shannack has picked the wrong mark. Galva is a knight, a survivor of the brutal goblin wars, and handmaiden of the goddess of death. She is searching for her queen, missing since a distant northern city fell to giants. Tor On Sale: May 25/21 Unsuccessful in his robbery and lucky to escape with his life, Kinch now finds 5.38 x 8.25 • 416 pages his fate entangled with Galva's. Common enemies and uncommon dangers 9781250621191 • $34.99 • CL - With dust jacket force thief and knight on an epic journey where goblins hunger for human Fiction / Fantasy / Epic flesh, krakens hunt in dark waters, and honor is a luxury few can afford. Notes The Blacktongue Thief is fast and fun and filled with crazy magic. I can't wait to see what Christopher Buehlman does next." - Brent Weeks, New York Times bestselling author of the Lightbringer series Promotion " National print and online publicity campaign Dazzling. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Monday, January 30, 2012 1:44:57PM School: Firelands Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 46618 EN Cats! Brimner, Larry Dane LG 0.3 0.5 49 F 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 31584 EN Big Brown Bear McPhail, David LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 84997 EN Colors and the Number 1 Sargent, Daina LG 0.4 0.5 81 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor LG 0.5 0.5 77 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 31858 EN Hop, Skip, Run Leonard, Marcia LG 0.5 0.5 110 F 26922 EN Hot Rod Harry Petrie, Catherine LG 0.5 0.5 63 F 69269 EN My Best Friend Hall, Kirsten LG 0.5 0.5 91 F 60939 EN Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari LG 0.5 0.5 110 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 26927 EN Bubble Trouble Hulme, Joy N. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1989 Naked Once More by 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show Best Contemporary Novel Elizabeth Peters by Richard Laymon (Formerly Best Novel) 1988 Something Wicked by 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub Carolyn G. Hart 1998 Bag Of Bones by Stephen 2017 Glass Houses by Louise King Penny Best Historical Novel 1997 Children Of The Dusk by 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Janet Berliner Penny 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen 2015 Long Upon The Land by Bowen King Margaret Maron 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates 2014 Truth Be Told by Hank by Catriona McPherson 1994 Dead In the Water by Nancy Philippi Ryan 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. Holder 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank King 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub Philippi Ryan 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1992 Blood Of The Lamb by 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by Bowen Thomas F. Monteleone Louise Penny 2013 A Question of Honor by 1991 Boy’s Life by Robert R. 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret Charles Todd McCammon Maron 2012 Dandy Gilver and an 1990 Mine by Robert R. 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Unsuitable Day for McCammon Penny Murder by Catriona 1989 Carrion Comfort by Dan 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise McPherson Simmons Penny 2011 Naughty in Nice by Rhys 1988 The Silence Of The Lambs by 2008 The Cruelest Month by Bowen Thomas Harris Louise Penny 1987 Misery by Stephen King 2007 A Fatal Grace by Louise Bram Stoker Award 1986 Swan Song by Robert R. -

Hugo Awards Presentation Chicenv

Hugo Awards Presentation ChicenV The 49th World Science Fiction Convention 29 August through 2 September 1991 Chicon V, Inc "World Science Fiction Society", "WSFS", "World Science Fiction Convention", "NASFiC", "Science Fiction Achievement Award, and "Hugo Award" are Service Marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. Hugo Program Book produced and edited by Jane G. Haldeman and Tina L. Jens Cover Art by Donna E. Slager Special Thanks to XPRESS GRAPHICS LINOTYPE IMAGESETTING 137 North Oak Park Ave Suite 200 Oak Park, IL 60301 708-848-8651 The Hugo Award The Hugo is Science Fiction’s Achievement Award. The name “Hugo" is for Hugo Gernsback. Nominees are chosen for publication or activities in the previous calendar year. Hugos have been awarded annually at the World Science Fiction Convention since 1953. The only exception was 1954 when the idea was dropped for a year. The award is in the shape of a rocket ship based on an Oldsmobile hood ornament. The original designs were created by Ben Jason (in 1955) and Jack McKnight. If you would like to know more there is an article in the Chicon V Program book. This Year’s Presenters Master of Ceremonies Marta Randall Hugo Balloting Committee Darrell Martin Ross Pavlac Chicon V Special Award Kathleen Meyer First Fandom’s Award Frederik Pohl Japan’s Seiun-Sho Takumi Shibano John W Campbell Award Stanley Schmidt The Hugo Ceremony Staff Department Head Jane G. Haldeman Assistant Department Head Tina L. Jens Secret Advisor Douglas H. Price D.l. House Manager George Krause Hugo Envoy Crew Martin Costello Nancy Mildebrand Martha Fabish John Mitchell Winifred Halsey Eve Schwingel William Henry Hay, M.D. -

University-Industry (Et Al.) Interaction in Science Fiction

Fiction lagging behind or non-fiction defending the indefensible? University-industry (et al.) interaction in science fiction Joaquín M. Azagra-Caro1,*, Laura González-Salmerón2, Pedro Marques1 1 INGENIO (CSIC-UPV), Universitat Politècnica de València, Camino de Vera s/n, E-46022 Valencia, Spain 2 Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, University of Oxford ABSTRACT University-industry interaction has supporters and detractors in the scholarly literature. Whereas policymakers have mainly joined the former, science fiction authors have predominantly enrolled the latter. We illustrate how the genre has been critical to university-industry interaction via the analysis of the most positively acclaimed novels from the 1970s to date. We distinguish the analytical dimensions of type of conflict, and innovation helices involved other than university (industry, government, society). By doing so, we merge two streams of literature that had not encountered before: university-industry interaction and representations of science in popular culture. A methodological novelty is the creation of an objective corpus of the literature to increase external validity. Insights include the relevance of the time context, with milder views or disinterest on university-industry interaction in science fiction works after the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act; and the lack of an academic or policy narrative about the benefits of university-industry interaction so convincing as to permeate into popular culture. Discourse is crucial for legitimising ideas, and university-industry interaction may have not found the most appropriate yet. Keywords: university-industry interaction, conflicts, representations of science * Corresponding author. Tel.: +34963877007; fax: +34963877991. E-mail address: [email protected] 1 1. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F. -

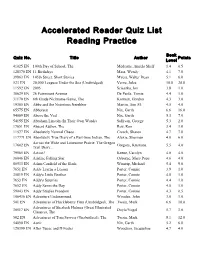

AR Quiz List by Title

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Reading Practice Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 128370 EN 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7.0 39863 EN 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 5.1 6.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 31170 EN 6th Grade Nickname Game, The Korman, Gordon 4.3 3.0 19385 EN Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Martin, Ann M. 4.5 4.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 54089 EN Above the Veil Nix, Garth 5.3 7.0 54155 EN Abraham Lincoln (In Their Own Words) Sullivan, George 5.3 2.0 17651 EN Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 3.4 1.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 117771 EN Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian, The Alexie, Sherman 4.0 6.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary... 79585 EN Action! Keene, Carolyn 4.8 4.0 36046 EN Adaline Falling Star Osborne, Mary Pope 4.6 4.0 86533 EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Winerip, Michael 5.4 9.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 35819 EN Addy's Little Brother Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 59043 EN Addy Studies Freedom Porter, Connie 4.3 0.5 106436 EN Adventure Underground Wooden, John 3.0 1.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Great Illustrated 30517 EN Doyle/Vogel 5.7 3.0 Classics), The 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 54090 EN Aenir Nix, Garth 5.2 6.0 120399 EN After Tupac and D Foster Woodson, Jacqueline 4.7 4.0 353 EN Afternoon of the Elves Lisle, Janet Taylor 5.0 4.0 14651 EN Afternoon on the Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 2.6 1.0 119440 EN Airman Colfer, Eoin 5.8 16.0 5051 EN Alan and Naomi Levoy, Myron 3.3 5.0 19738 EN Alaskan Adventure, The Dixon, Franklin W.