Joslyn Magdalene Hardine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government System Systems

GovernmentGovernment system systems YEARBOOK 2011/12 Government system 11 The Government of South Africa is committed to The Constitution building a free, non-racial, non-sexist, democratic, South Africa’s Constitution is one of the most united and successful South Africa. progressive in the world and enjoys high acclaim The outcomes approach, which started in 2010, internationally. Human rights are given clear is embedded in and a direct result of the electoral prominence in the Constitution. mandate. Five priority areas have been identified: The Constitution of the Republic of South decent work and sustainable livelihoods, educa- Africa, 1996 was approved by the Constitutional tion, health, rural development, food security and Court on 4 December 1996 and took effect on land reform and the fight against crime and cor- 4 February 1997. ruption. These have been translated into the fol- The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. lowing 12 outcomes to create a better life for all: No other law or government action can supersede • better quality basic education the provisions of the Constitution. • a long and healthy life for all South Af- ricans The Preamble • all South Africans should be safe and feel safe The Preamble states that the Constitution aims • decent employment through inclusive growth to: • a skilled and capable workforce to support an • heal the divisions of the past and establish a inclusive growth path society based on democratic values, social Government systems• an efficient, competitive and responsive eco- justice -

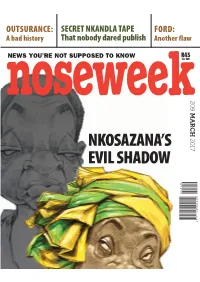

Nkosazana's Evil Shadow

OUTSURANCE: SECRET NKANDLA TAPE FORD: A bad history That nobody dared publish Another flaw R45 NEWS YOU’RE NOT SUPPOSED TO KNOW (inc VAT) noseweek209 MARCH MARCH NKOSAZANA’S 2017 EVIL SHADOW 00209 104042 771025 9 GB NoseWeek MCC Ad_02.indd 1 2016/12/12 2:03 PM Your favourite magazine is now ISSUE 209 • MARCH 2017 available on your iPad and PC Stent Page 10 FEATURES 9 Notes & Updates 4 Letters Appeal against Tongaat-Hulett pensions ruling 8 Editorial n Mpisanes: the paper chase n Second guessing America First 38 Smalls 12 Nkosazana’s evil shadow AVAILABLE Bathabile Dlamini’s history of dishonesty and disasterous mismanagement of SA’s social grants ON YOUR COLUMNS programme likely to sink Nkosazana’s chances of TABLET becoming president 33 Africa 13 A shocking taped phone conversation 34 Books A leaked recording draws the spotlight onto the financial and political ambitions of Zuma’s women Download your 35 Down & digital edition today Out 16 Road swindle: tarred and feathered Contractor overcharged hugely 36 Letter from both single issues and Umjindi 20 Petrol consumption figures fuel Ford’s fire subscriptions available 37 Last Word Doughty widow challenges advertising claims PLUS never miss a copy – 22 Sweet talk with back issues available to A brand of purportedly diabetic-friendly agave download and store nectar is putting South African lives at risk 26 Leuens Botha and the weird weir DOWNLOAD YOUR DIGITAL The many faces and many schemes of a DA politician EDITION AT 28 Bad policy www.noseweek.co.za How to fight insurance claim blackmail or % 021 686 0570 30 On wings of song Cape Town’s Youth Choir plans to conquer New York NOSEWEEK March 2017 3 Letters Barry Sergeant an instant friend the scales of the legal minions slith- calls and trips to various places ering around Facebook instead of they have told her it’s her own fault I’M SO SAD ABOUT BARRY SERGEANT’S respecting your right to a healthy and said someone has been buying death. -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

HIV & AIDS and Wellness

HIV & AIDS and Wellness WESTERN CAPE BUSINESS SECTOR PROVINCIAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2011–2015 ‘Taking responsibility to create a summer for all’ SABCOHA CONTACT DETAILS Physical address: 3rd Floor 158 Jan Smuts Ave Rosebank Johannesburg Postal address: PO Box 950 Parklands 2121 Tel: +27 11 880 4821 Fax: +27 11 880 6084 Email: [email protected] www.sabcoha.org SABCOHA Empowering Business in the fight against HIV HIV & AIDS AND WELLNESS WESTERN CAPE BUSINESS SECTOR PROVINCIAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2011–2015 ‘Taking responsibility to create a summer for all’ 2 HIV & AIDS AND WELLNESS: WESTERN CAPE BUSINESS SECTOR PROVINCIAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2011–2015 The message of the successes in the fight to reduce the spread of HIV and AIDS in the Western Cape is reaching the whole spectrum of communities, and this success can be attributed to the integration of the forces of government and the private sector. Now it is time for us to put the strategy into action. — Mr Theuns Botha, Western Cape Minister of Health, March 2011 3 HIV & AIDS AND WELLNESS: WESTERN CAPE BUSINESS SECTOR PROVINCIAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2011–2015 Table of contents ACRONYMS 5 GLOSSARY OF TERMS 6 FOREWORD 7 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 2. BACKGROUND 11 3. CONTEXT OF IMPLEMENTATION 13 Western Cape Province 13 City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality 19 West Coast district municipality 22 Cape Winelands district municipality 23 Overberg district municipality 24 Eden district municipality 25 Central Karoo district municipality 27 4. DEVELOPMENT OF THIS PLAN 29 Background 29 Survey 30 Strategy development 31 Branch establishment 31 5. BUSINESS SECTOR WESTERN CAPE STRATEGIC PLAN 33 Introduction 33 Purpose 34 Live the Future scenarios 34 Guiding principles 35 Interventions and approach 36 10-point priority plan 45 4 HIV & AIDS AND WELLNESS: WESTERN CAPE BUSINESS SECTOR PROVINCIAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2011–2015 6. -

Sitting(Link Is External)

1 TUESDAY, 27 MARCH 2018 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT The sign † indicates the original language and [ ] directly thereafter indicates a translation. The House met at 10:00. The Speaker took the Chair and read the prayer. The SPEAKER: Please be seated. Good morning, hon members. It is indeed a pleasure for me to welcome you. To our guests in the gallery and also the staff, welcome to the sitting today. I just need to remind the guests in the gallery, we appreciate your being here, however you are not allowed to participate in the proceedings of the House. I will now ask the Secretary to read the First Order of the Day. The SECRETARY: Debate on Vote 11 – Agriculture – Western Cape Appropriation Bill [B 3 - 2018]. The PREMIER: Hear-hear! The SPEAKER: I see the honourable, the Minister, Minister Winde. 2 [Applause.] The MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND TOURISM: Thank you very much. Madam Speaker, Premier, Cabinet colleagues, members of this House, the Head of Department and the Department of Agriculture, the citizens of this province: It is impossible to stand here today and address you on the state of agriculture in the province and not mention the drought. Madam Speaker, I know you have not seen me here in a jacket of late, so if you do not mind, I am going to take my jacket off because, as this House knows, from 1 February or Level 6B water restrictions, I have been wearing jeans and a T-shirt to work for three days in a row before I wash them. -

Representation of South African Women in the Public Sphere

REPRESENTATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE PREPARED BY ADITI HUNMA, RESEARCH ASSISTANT 1 REPRESENTATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE METHODOLOGY The aim of this report is to explore how South African women are (re)presented by the media as they engage in the public sphere. It looks at women in three different fields namely, politics, business and art, analysing at the onset the way they argue, that is, as rhetorical agents. It ihen proceeds to assess how these women's gender is perceived to enhance or be detrimental to their capacity to deliver. In the process, the report comes to belie and confront various myths that still persist and taint women's image in the public arena. In the realm of politics, I will be analysing Cape Town Mayor and Head of DA, Helen Zille. In the corporate world, I will be looking at Bulelwa Qupe, who owns the Ezabantu, long-line Hake fishing company, and in the Arts, I will be looking at articles published on Nadine Gordimer, the author who bagged the Nobel Literature Prize less than two decades back. Data for this purpose was compiled from various websites, namely SABCNews.com, Mail and Guardian, News24, IOL and a few blog sites. It was then perused, sorted and labelled. Common topos were extracted and portions dealing with the (re)presentation of women were summarised prior to the actual write up. In the course of the research, I realised that the framing of events had a momentous bearing on the way the women came to be appear and so, I paid close attention to titles, captions and emboldened writings. -

Journal of African Elections Special Issue South Africa’S 2014 Elections

remember to change running heads VOLUME 14 NO 1 i Journal of African Elections Special Issue South Africa’s 2014 Elections GUEST EDITORS Mcebisi Ndletyana and Mashupye H Maserumule This issue is published by the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) in collaboration with the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA) and the Tshwane University of Technology ARTICLES BY Susan Booysen Sithembile Mbete Ivor Sarakinsky Ebrahim Fakir Mashupye H Maserumule, Ricky Munyaradzi Mukonza, Nyawo Gumede and Livhuwani L Ndou Shauna Mottiar Cherrel Africa Sarah Chiumbu Antonio Ciaglia Mcebisi Ndletyana Volume 14 Number 1 June 2015 i ii JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 11 381 6000 Fax: +27 (0) 11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] ©EISA 2015 ISSN: 1609-4700 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher Printed by: Corpnet, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA www.eisa.org.za remember to change running heads VOLUME 14 NO 1 iii EDITOR Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg MANAGING AND COPY EDITOR Pat Tucker EDITORIAL BOARD Chair: Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg Jørgen Elklit, Department of Political Science, University -

Democratic Alliance Candidates' Lists 2009

DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE CANDIDATES’ LISTS 2009 ELECTION EASTERN CAPE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST 1. Athol Trollip 2. Annette Lovemore 3. Donald Lee 4. Stuart Farrow 5. Donald Smiles 6. Annette Steyn 7. Elza van Lingen 8. Peter van Vuuren 9. Gustav Rautenbach 10. Kevin Mileham PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURE LIST 1. Athol Trollip 2. Bobby Stevenson 3. Veliswa Mvenya 4. John Cupido 5. Pine Pienaar 6. Dacre Haddon 7. Peter Van Vuuren 8. Kevin Mileham 9. Isaac Adams 10. Mzimkhulu Xesha FREE STATE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST 1. Cobus Schmidt 2. Semakaleng Patricia Kopane 3. Theo Coetzee 4. Annelie Lotriet 5. Darryl Worth 6. David Ross 7. Ruloph Van der Merwe 8. Helena Hageman 9. Kingsley Ditabe PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURE LIST 1. Roy Jankielsohn 2. Peter Frewen 3. Basil Alexander 4. David Janse van Vuuren 5. Henk van der Walt 6. David Ross 7. Nicolene du Toit 8. Tseko Mpakate GAUTENG NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST 1. Ian Davidson 2. Sej Motau 3. Butch Steyn 4. Natasha Michael 5. Niekie Van der Berg 6. Anthea Jeffrey 7. Kenneth Mubu 8. Manny de Freitas 9. Mike Waters 10. Stevens Mokgalapa 11. James Lorimer 12. Ian Ollis 13. Marti Wenger 14. Juanita Kloppers-Lourens 15. Anchen Dreyer 16. Dion George 17. Manie van Dyk 18. Hendrik Schmidt 19. Emmah More 20. George Boinamo 21. Justus de Goede 22. Rika Kruger 23. Sherry Chen 24. Anthony Still 25. Shelley Loe 26. Kevin Wax 27. James Swart 28. Bev Abrahams 29. Don Forbes 30. Jan Boshoff 31. Wildri Peach 32. Danie Erasmus 33. Frank Van der Tas 34. Johan Jordaan 35. Cilicia Augustine 36. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Attacks, Our 2009 Elections Is Not the Only Crisis of Ethical Leadership We Have to Consider

Every Leader’s Paper - June 2008 - Page 1 The Ethical Leadership Project’s Official Newsletter June 2008 Edition - Issue No 6 ‘’We must accept finite disappointment but we must never lose infinite hope’’ (Martin Luther King) In South Africa, after our demoralising history of Apartheid, the more defective “Where have the heroes of our African our leaders, the more we long for highly story gone? Men and Women who are effective, ethical leaders. Regrettably, our not afraid of the night? Where are the leaders sometimes consciously act in leaders who stood up against a tidal unethical ways, because power and wave that was said to never wash up position lead them to believe that they are on a shore? What has happened to not bound by the same ethical norms as courage under fire that crafted the Find out about the the rest of society. stories that have reached every corner of the earth? We’re calling out… come ELP’s POLITICS As we embrace the dawn of the 2009 out of hiding. You who were once the CONFERENCE on elections, we need to remember that great, the hopeful, the bold. Come out PAGE 2 sometimes leaders who have “little power of hiding you who once defied the and standing in the community come to ways of the old and looked not to the believe their own propaganda’’ and “have past but leaned hard into the future. no guiding morality and are driven solely Come out into the open, you were once by the pursuit of self-furtherance” (Andrew not afraid of the sweat of the fire Stephen). -

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa PO Box 740 Auckland park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 011 381 6000 Fax: +27 011 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 978-1-920446-45-1 © EISA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2014 EISA acknowledges the contributions made by the EISA staff, the regional researchers who provided invaluable material used to compile the Updates, the South African newspapers and the Update readers for their support and interest. Printing: Corpnet, Johannesburg CONTENTS PREFACE 7 ____________________________________________________________________ ELECTIONS IN 2014 – A BAROMETER OF SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS AND 9 SOCIETY? Professor Dirk Kotze ____________________________________________________________________ 1. PROCESSES ISSUE 19 Ebrahim Fakir and Waseem Holland LEGAL FRAMEWORK 19 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN ELECTORAL LAW 21 ELECTION TIMETABLE 24 ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 25 NEGATIVE PERCEPTIONS OF ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 26 ELECTORAL SYSTEM 27 VOTING PROCESS 28 WORKINGS OF ELECTORAL SYSTEM 29 COUNTING PROCESS 30 2014 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS – VOTER REGISTRATION 32 STATISTICS AND PARTY REGISTRATION ____________________________________________________________________ 2. SA ELECTIONS 2014: CONTINUITY, CONTESTATION OR CHANGE? 37 THE PATH OF THE PAST: SOUTH AFRICAN DEMOCRACY TWENTY YEARS ON 37 Professor Steven Friedman KWAZULU-NATAL 44 NORTH WEST 48 LIMPOPO 55 FREE STATE 59 WESTERN CAPE 64 MPUMALANGA 74 GAUTENG 77 ____________________________________________________________________ 3 3. -

Government System

GOVERNMENT SYSTEM SOUTH AFRICA YEARBOOK 2010/11 2010/11 GOVERNMENT SYSTEM 11 The Government of South Africa committed government are working together to achieve itself to investing in the preparations needed the outcomes. to ensure that Africa’s first FIFA World CupTM Delivery agreements are collective agree- was a resounding success. Government ments that involve all spheres of government also used this opportunity to speed up the and a range of partners outside government. delivery of services and infrastructure. Combined, these agreements will reflect Various government departments that government’s delivery and implementation made guarantees to FIFA delivered on their plans for its priorities. mandates within the set deadlines. Govern- They serve as a basis for reaching agree- ment is committed to drawing on the suc- ment with multiple agencies that are central cess of the World Cup to take the delivery of to the delivery of the outcome targets. major projects forward. The President regularly visits service- The outcomes approach is embedded delivery sites to monitor progress. The pur- in and a direct resultant of the electoral pose of these site visits is for the President mandate. Five priority areas were identified: to gain first-hand experience of service decent work and sustainable livelihoods; delivery and to highlight issues that need to education; health; rural development; food be worked on by the various arms of gov- security and land reform; and the fight ernment. against crime and corruption. These trans- lated into 12 outcomes to create a better life The Constitution for all: South Africa’s Constitution is one of the • an improved quality of basic education most progressive in the world and enjoys • a long and healthy life for all South Af- high acclaim internationally. -

Thursday, 25 August 2016

1 THURSDAY, 25 AUGUST 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT The sign † indicates the original language and [ ] directly thereafter indicates a translation . The House met at 14:15. The Speaker took the Chair and read the prayer. ANNOUNCEMENTS, TABLING AND COMMITTEE REPORTS - see p The DEPUTY SPEAKER: You may be seated. Before we proceed I would like to make some comments about the logistical arrangements. Because of the unavailability of our chamber in 7 Wale Street, this chamber, Good Hope Sub-council Chambers here at 44 Wale Street will be used temporarily for House sittings from today until further notice. Please also note that in compliance with the Powers, Privileges and Immunities of Parliaments and Provincial Legislatures Act, 2004, this chamber, the gallery, the lobbies, and adjacent passage and ablution facilities as well as the committee room on the 12th floor will be regarded as the 2 precinct of the Provincial Parliament. In terms of the audio controls, to enable a member to talk, the member should push the talk button on the microphone speaker unit fitted on the desk. There is one unit for every two to three members to share. The member speaking need not move to a microphone. The system is strong enough to pick up sound from your allocated seat. Members seated in close proximity to a speaker must therefore be aware that any loud conversation may interfere with the recording of the speaker on the floor. In order to select your language of choice, when it comes to interpreting please press the channel button on your wireless receiver to select the correct channel.