Sergei Medvedev Thesis 1.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6Th Lily Supplement

The International Lily Register & Checklist (2007) Sixth Supplement © 2019 The Royal Horticultural Society 80 Vincent Square, London SW1P 2PE, United Kingdom www.rhs.org.uk Charity registration number 222879 / SC038262 International Registrar: Duncan Donald E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder ISBN 9781907057960 Printed and bound in the UK by Page Bros, Norwich (MRU) The previous supplement (Fifth Supplement) was published on 13th February 2017 Cover: Lilium ‘Willcrovidii’; drawing of Award of Merit plant by Winifred Walker, 1932. Image courtesy of RHS Herbarium, Wisley The International Lily Register and Checklist 2007 Sixth Supplement Introduction page 1 Notes on the entries page 2 Horticultural Classification page 4 Register and Checklist page 6 List of registrants page 116 The lily epithets listed here were registered between 1 September 2014 and 31 August 2016. Details of lilies with unregistered names are published also, as a Checklist, as are significant amendments to existing registrations. Epithets which conformed to the Articles (and, ideally, Recommendations) of the 2009 edition of the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP) were deemed acceptable for registration [though entries have subsequently been updated to the 2016 edition, including the new use of adopted epithets]. Although registration is a voluntary procedure and does not confer any legal protection on the plant, the Royal Horticultural Society – as International Cultivar Registration Authority for Lilium – urges all hybridizers, raisers and introducers to register their lily names, to minimize potential confusion caused by new epithets the same as, or very similar to, existing names. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

AACS 2017 Program

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR CHINESE STUDIES 59TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM OCTOBER 20-22, 2017 Hosted by Walker Institute University of South Carolina Columbia, South Carolina PROGRAM OVERVIEW Hotel Courtyard by Marriott Downtown at USC 630 Assembly Street Columbia, S.C. 29201 Phone: 803-799-7800 Fax: 803-254-6842 www.Marriott.com/caecd Conference Location Darla Moore School of Business 1014 Greene Street Columbia, S.C. 29208 1 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2017 6:30-6:50 pm Welcoming Remarks Courtyard by Marriott, Lexington Room (2nd Floor) John Hsieh President American Association for Chinese Studies Robert Cox Director Walker Institute of International and Area Studies University of South Carolina 6:50-9:00 pm Reception Courtyard by Marriott, Lexington Room (2nd Floor) SATURDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2017 6:45-8:00 am AACS Board Meeting Courtyard by Marriott, Richland Room 8:30-10:00 am Panel Session One Darla Moore School of Business Rooms 103, 120, 121, 122, 125, 126 10:00-10:15 am Coffee Break Darla Moore School of Business 2nd Floor Sonoco Pavilion Room 10:15-11:45 am Panel Session Two Darla Moore School of Business 2 Rooms 103, 120, 121, 122, 125, 126 12:00 noon-1:30 pm Luncheon Darla Moore School of Business 2nd Floor Sonoco Pavilion Room 1:45-3:15 pm Panel Session Three Darla Moore School of Business Rooms 103, 120, 121, 122, 125, 126 3:15-3:30 pm Coffee Break Darla Moore School of Business 2nd Floor Sonoco Pavilion Room 3:30-5:00 pm Panel Session Four Darla Moore School of Business Rooms 103, 120, 121, 122, 125, 126 6:30-9:00 pm Banquet and Keynote -

Franquicia Televisiva En Formato Talent Show Infantil Y La Gestualidad En La Performance Del Canto1

Correspondencias & Análisis, 10, julio-diciembre 2019 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución- NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional ISSN 2304-2265 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Franquicia televisiva en formato talent show infantil y la gestualidad en la performance del canto1 Recibido: 07/08/2019 Maria Thaís Firmino da Silva Aceptado: 29/10/2019 [email protected] Publicado: 05/12/2019 Universidade Federal do Ceará (Brasil) Maria Érica de Oliveira Lima [email protected] Universidade Federal do Ceará (Brasil) Resumen: Considerando la proliferación de formatos televisivos globales, esta investigación analizó la relación específica entre los medios de comuni- cación y la música en el programa “The Voice Brasil Kids 2018”. El propó- sito fue entender cómo la gestualidad evidenciada genera una brecha entre las características infantiles del talent show y los significados implementa- dos en performances previamente determinadas. Este estudio cualitativo (con investigación bibliográfica, análisis de contenido, análisis estructural) pre- senta argumentos sobre aspectos que implican producciones en formatos y se establece por el sesgo de análisis que reconoce el gesto como elemento de comunicación con significativo impacto en la performance mediatizada técnicamente. Por último, esta investigación señala que la brecha entre la es- pecificidad infantil del programa y la gestualidad (implementada en actuacio- nes previamente determinadas) se apoya en el uso de gestos con significados orientados a la esfera adulta y que el repertorio también puede reforzar esta perspectiva. 1. Este artículo forma parte del resultado presentado en la tesis de maestría en comunicación, titulada “Franquia televisiva em formato talent show infantil e a gestualidade na performance do canto”, defendida por Firmino da Silva (2019) en la Universidade Federal de Ceará (Brasil). -

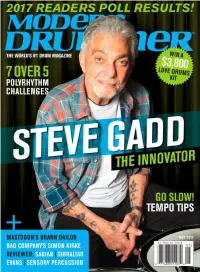

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Iacs2017 Conferencebook.Pdf

Contents Welcome Message •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Conference Program •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Conference Venues ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 Keynote Speech ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Plenary Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 Special Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 34 Parallel Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40 Travel Information •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 228 List of participants ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 232 Welcome Message Welcome Message Dear IACS 2017 Conference Participants, I’m delighted to welcome you to three exciting days of conferencing in Seoul. The IACS Conference returns to South Korea after successful editions in Surabaya, Singapore, Dhaka, Shanghai, Bangalore, Tokyo and Taipei. The IACS So- ciety, which initiates the conferences, is proud to partner with Sunkonghoe University, which also hosts the IACS Con- sortium of Institutions, to organise “Worlding: Asia after/beyond Globalization”, between July 28 and July 30, 2017. Our colleagues at Sunkunghoe have done a brilliant job of putting this event together, and you’ll see evidence of their painstaking attention to detail in all the arrangements -

VAN JA 2021.Indd

Lismore Castle Arts ALICIA REYES MCNAMARA Curated by Berlin Opticians LIGHT AND LANGUAGE Nancy Holt with A.K. Burns, Matthew Day Jackson, Dennis McNulty, Charlotte Moth and Katie Paterson. Curated by Lisa Le Feuvre 28 MARCH - 10 JULY - 10 OCTOBER 2021 22 AUGUST 2021 LISMORE CASTLE ARTS, LISMORE CASTLE ARTS: ST CARTHAGE HALL LISMORE CASTLE, LISMORE, CHAPEL ST, LISMORE, CO WATERFORD, IRELAND CO WATERFORD, IRELAND WWW.LISMORECASTLEARTS.IE +353 (0)58 54061WWW.LISMORECASTLEARTS.IE Image: Alicia Reyes McNamara, She who comes undone, 2019, Oil on canvas, 110 x 150 cm. Courtesy McNamara, She who comes undone, 2019, Oil on canvas, of the artist Image: Alicia Reyes and Berlin Opticians Gallery. Nancy Holt, Concrete Poem (1968) Ink jet print on rag paper taken from original 126 format23 transparency x 23 in. (58.4 x 58.4 cm.). 1 of 5 plus AP © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. VAN The Visual Artists’ Issue 4: BELFAST PHOTO FESTIVAL PHOTO BELFAST FILM SOCIETY EXPERIMENTAL COLLECTION THE NATIONAL COLLECTIVE ARRAY Inside This Issue July – August 2021 – August July News Sheet News A Visual Artists Ireland Publication Ireland A Visual Artists Contents Editorial On The Cover WELCOME to the July – August 2021 Issue of within the Irish visual arts community is The Visual Artists’ News Sheet. outlined in Susan Campbell’s report on the Array Collective, Pride, 2019; photograph by Laura O’Connor, courtesy To mark the much-anticipated reopening million-euro acquisition fund, through which Array and Tate Press Offi ce. of galleries, museums and art centres, we 422 artworks by 70 artists have been add- have compiled a Summer Gallery Guide to ed to the National Collection at IMMA and First Pages inform audiences about forthcoming exhi- Crawford Art Gallery. -

CTC Media Investor Presentation

CTC Media, Inc. Investor Presentation May 2014 A Leading Independent Broadcasting and Content Company in Russia From Private TV Network to Public Media Holding Launch of CTC- international in Germany, North America and the Baltics Development of in- house creative Telcrest Investments production center Limited acquired a 25% CTC Media was stake in СTС Media Launch of Peretz from Alfa Group founded as Story International in Modern Times Group First Initial Public Offering Belarus became a shareholder Launch of Domashniy.ru Communications on NASDAQ Launch of CTC- of CTC Media international in women’s portal USA 1989 1994 2002 2005 2006 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Launch of CTC Launch of CTC- Love Channel on international in cable and satellite Launch of CTC Launch of Israel Acquisition of DTV Launch of CTC- Network Domashny Network Launch of Peretz (rebranded to Peretz international in Establishment of International in in 2011) Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, CTC Media’s Kyrgystan Armenia, Georgia, internal advertising Acquisition of Azerbaijan, Thailand and sales house Launch of Sweet Channel 31 in uplink to HOT BIRD ‘Everest Sales’ me brand together Kazakhstan and a TV with KupiVip company in Moldova CTC and Domashny Launch of received digital licenses Videomore.ru online content portal 2 We Fully Capture the Value Chain by Being Integrated TV Broadcaster CTC – target audience All 10-45 BROADCASTING ( RUSSIA) Domashny – target audience Females 25-59 Peretz – target audience All 25-49 CTC Love – target audience All 11-34 Kazakhstan Channel -

Negotiating Musicianship Live Weider Ellefsen

Ellefsen Weider Live Live Weider Ellefsen In this ethnographic case-study of a Norwegian upper secondary music musicianship Negotiating programme – “Musikklinja” – Live Weider Ellefsen addresses questions of Negotiating musicianship subjectivity, musical learning and discursive power in music educational practices. Applying a conceptual framework based on Foucault’s discourse The constitution of student subjectivities theory and Butler’s theory of (gender) performativity, she examines how the young people of Musikklinja achieve legitimate positions of music student- in and through discursive practices of hood in and through Musikklinja practices of musicianship, across a range of sites and activities. In the analyses, Ellefsen shows how musical learn- musicianship in “Musikklinja” ers are constituted as they learn, subjecting themselves to and perform- ing themselves along relations of power and knowledge that also work as means of self-understanding and discursive mastery. The study’s findings suggest that dedication, entrepreneurship, compe- tence, specialization and connoisseurship are prominent discourses at play in Musikklinja. It is by these discourses that the students are socially and institutionally identified and addressed as music students, and it is by understanding themselves in relation to these discourses that they come to be music student subjects. The findings also propose that a main charac- teristic in the constitution of music student subjectivity in Musikklinja is the appropriation of discourse, even where resistance can be noted. However, within the overall strategy of accepting and appropriating discourses of mu- sicianship, students subtly negotiate – adapt, shift, subvert – the available discourses in ways that enable and empower their discursive legitimacy. Musikklinja constitutes an important educational stepping stone to higher music education and to professional musicianship in Norway. -

The Anti-Imperial Choice This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Anti-Imperial Choice the Making of the Ukrainian Jew

the anti-imperial choice This page intentionally left blank The Anti-Imperial Choice The Making of the Ukrainian Jew Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern Yale University Press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Ehrhardt type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. The anti-imperial choice : the making of the Ukrainian Jew / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-13731-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Jewish literature—Ukraine— History and criticism. 2. Jews in literature. 3. Ukraine—In literature. 4. Jewish authors—Ukraine. 5. Jews— Ukraine—History— 19th century. 6. Ukraine—Ethnic relations. I. Title. PG2988.J4P48 2009 947.7Ј004924—dc22 2008035520 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). It contains 30 percent postconsumer waste (PCW) and is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). 10987654321 To my wife, Oxana Hanna Petrovsky This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Politics of Names and Places: A Note on Transliteration xiii List of Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 chapter 1. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2019

INSIDE: UWC leadership meets with Zelenskyy – page 3 Lomachenko adds WBC title to his collection – page 15 Ukrainian Independence Day celebrations – pages 16-17 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association, Inc., celebrating W its 125th anniversaryEEKLY Vol. LXXXVII No. 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2019 $2.00 Trump considers suspension of military aid Zelenskyy team takes charge to Ukraine, angering U.S. lawmakers as new Rada begins its work RFE/RL delay. Unless, of course, he’s yet again act- ing at the behest of his favorite Russian dic- U.S. President Donald Trump is consid- tator & good friend, Putin,” the Illinois sena- ering blocking $250 million in military aid tor tweeted. to Ukraine, Western media reported, rais- Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.), a member of ing objections from lawmakers of both U.S. the House Foreign Affairs Committee, tweet- political parties. ed that “This is unacceptable. It was wrong Citing senior administration officials, when [President Barack] Obama failed to Politico and Reuters reported that Mr. stand up to [Russian President Vladimir] Trump had ordered a reassessment of the Putin in Ukraine, and it’s wrong now.” aid program that Kyiv uses to battle Russia- The administration officials said chances backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. are that the money will be allocated as The review is to “ensure the money is usual but that the determination will not be being used in the best interest of the United made until the review is completed and Mr. States,” Politico said on August 28, and Trump makes a final decision. -

Gratifications About Reality Television “The Voice of China” Among Chinese Audience

GRATIFICATIONS ABOUT REALITY TELEVISION “THE VOICE OF CHINA” AMONG CHINESE AUDIENCE GRATIFICATIONS ABOUT REALITY TELEVISION “THE VOICE OF CHINA” AMONG CHINESE AUDIENCE Xin Zhao This Independent Study Manuscript Presented to The Graduate School of Bangkok University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Communication Arts 2014 ©2014 Xin Zhao AllRight Reserved Xin Zhao, Master of Communication, July 2014, Graduate School, Bangkok University. Gratifications about Reality Television “The Voice of China” among Chinese Audience (66 pp.) Advisor : Assoc. Prof. Boonlert Supadhiloke, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The main objective of this study is to apply the uses and gratifications approach to investigate “The Voice of China”, the most successful talent show in china for past two years. The research examines the motives for watching and satisfaction of audience through comparing the gratifications sought and gratifications obtained. A quantitative survey is be used to collect data. The samples are selected by convenience sampling method and all of the samples are 231. The mean and standard deviation are tabulated and analyzed by using paired sample t-test. The finding suggests that the primary motives for watching “The Voice of China” among Chinese audiences are social interaction, entertainment and relaxing, but not vicarious participation or perceived reality. And the gratifications are well obtained indicates high audience satisfaction for the program content. v ACKNOWLEDGMENT My experience as a graduate student has been an exciting and challenging journey. I would like to acknowledge all of my committee members for their helpful suggestions and comments. First, I would like to thank Dr. Boonlert Supadhiloke, for his direction on this IS paper.