Conservation 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core Conservation Courses (Finh-Ga.2101-2109)

Conservation Course Descriptions—Full List Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts Page 1 of 38, 2/05/2020 CORE CONSERVATION COURSES (FINH-GA.2101-2109) MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY I FINH-GA.2101.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on problems related to the study and conservation of organic materials found in art and archaeology from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Enrollment is limited to conservation students and other qualified students with the permission of the faculty of the Conservation Center. This course is required for first-year conservation students. MATERIAL SCIENCE OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY II FINH-GA.2102.001 [#reg. code] (Lecture, 3 points) Instructor Hours to be arranged Location TBD The course extends over two terms and is related to Technology and Structure of Works of Art I and II. Emphasis during this term is on the chemistry and physics of inorganic materials found in art and archaeological objects from ancient to contemporary periods. The preparation, manufacture, and identification of the materials used in the construction and conservation of works of art are studied, as are mechanisms of degradation and the physicochemical aspects of conservation treatments. Each student is required to complete a laboratory assignment with a related report and an oral presentation. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: June 5, 2019 MEDIA CONTACTS: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] J. PAUL GETTY TRUST BOARD OF TRUSTEES ELECTS DR. DAVID L. LEE AS CHAIR Dr. David L. Lee has served on the Board since 2009; he begins his four-year term as chair on July 1 LOS ANGELES—The Board of Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust today announced it has elected Dr. David L. Lee as its next chair of the Board. “We are delighted that Dr. Lee will lead the Getty Board of Trustees as we embark on many exciting initiatives,” said Getty President James Cuno. “Dr. Lee’s involvement with the international community, his experience in higher education and philanthropy, and his strong financial acumen has served the Getty well. We look forward to his leadership.” Dr. Lee was appointed to the Getty Board of Trustees in 2009. Dr. Lee will serve a four-year term as chair of the 15-member group that includes leaders in art, education, and business who volunteer their time and expertise on behalf of the Getty. “Through its extensive research, conservation, exhibition and education programs, the Getty’s work has made a powerful impact not only on the Los Angeles region, but around the world,” Dr. Lee said. “I am honored to be part of such a generous, inspiring organization that makes a lasting difference and is a source of great pride for our community.” The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 Dr. -

Press Image Sheet

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: September 17, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] GETTY TO DEVOTE $100 MILLION TO ADDRESS THREATS TO THE WORLD’S ANCIENT CULTURAL HERITAGE Global initiative will enlist partners to raise awareness of threats and create effective conservation and education strategies Participants in the 2014 Mosaikon course Conservation and Management of Archaeo- logical Sites with Mosaics conduct a condition survey exercise of the Achilles Mosaic at the Paphos Archeological Park, Paphos, Cyprus. Continued work at Paphos will be undertaken as part of Ancient Worlds Now. Los Angeles – The J. Paul Getty Trust will embark on an unprecedented and ambitious $100- million, decade-long global initiative to promote a greater understanding of the world’s cultural heritage and its universal value to society, including far-reaching education, research, and conservation efforts. The innovative initiative, Ancient Worlds Now: A Future for the Past, will explore the interwoven histories of the ancient worlds through a diverse program of ground-breaking The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 scholarship, exhibitions, conservation, and pre- and post- graduate education, and draw on partnerships across a broad geographic spectrum including Asia, Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. “In an age of resurgent populism, sectarian violence, and climate change, the future of the world’s common heritage is at risk,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. -

Getty and Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage Announce Major Enhancements to Ghent Altarpiece Website

DATE: August 20, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE IMAGES OF THE RESTORED ADORATION OF THE LAMB AND MORE: GETTY AND ROYAL INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL HERITAGE ANNOUNCE MAJOR ENHANCEMENTS TO GHENT ALTARPIECE WEBSITE Closer to Van Eyck offers a 100 billion-pixel view of the world-famous altarpiece, to be enjoyed from home http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/ The Lamb of God on the central panel, from left to right: before restoration (with the 16th-century overpaint still present), during restoration (showing the van Eycks’ original Lamb from 1432 before retouching), after retouching (the final result of the restoration) LOS ANGELES AND BRUSSELS – Since 2012, the website Closer to Van Eyck has made it possible for millions around the globe to zoom in on the intricate, breathtaking details of the Ghent Altarpiece, one of the most celebrated works of art in the world. More than a quarter million people have taken advantage of the opportunity so far in 2020, and website visitorship has increased by 800% since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the potential for modern digital technology to increase access to masterpieces from all eras and learn more about them. The Getty and the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Brussels, Belgium), in collaboration with the Gieskes Strijbis Fund in Amsterdam, are giving visitors even more ways to explore this monumental work of art from afar, with the launch today of a new version of the site that includes images of recently restored sections of the paintings as well as new videos and education materials. Located at St. -

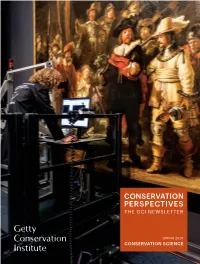

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

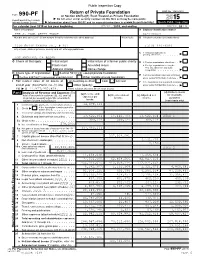

Attach to Your Tax Return. Department of the Treasury Attachment Sequence No

Public Inspection Copy Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning 07/01 , 2015, and ending 06/30, 20 16 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 95-1790021 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1200 GETTY CENTER DR., # 401 (310) 440-6040 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here LOS ANGELES, CA 90049 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test, check here and attach computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: CashX Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col. -

CATS Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CATS Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation The centre is a strategic research partnership between three Copenhagen based research institutions Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) The National Museum of Denmark (NMD) The School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation (KADK) The cornerstone of CATS is technical art history, which is an interdisciplinary field of research between conservators, natural scientists and scholars from art historical and cultural studies. Technical art history investigates the making and meaning of art works, painting techniques and artists’ materials. A main objective of the research centre is to develop new and more exact methods to diagnose, treat and preserve our art historical heritage. The exploration of artistic practices is aimed at shedding light on the complex and fascinating cartography of ageing processes within works of art – to contribute to and advance the field of technical art history. The establishment of the Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation was made possible by a donation by the Villum Foundation and the Velux Foundation, and is a collaborate research venture between Statens Museum for Kunst, the National Museum of Denmark and the School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation. Contact CATS Website: www.cats-cons.dk E-mail: [email protected] 2 CATS Annual Report, January - December 2018 Contents INTRODUCTION -

1 Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Ron Spronk Professor of Art History

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Ron Spronk Professor of Art History Department of Art History and Art Conservation Ontario Hall, Room 322 67 University Avenue Kingston, Ontario Canada K7L 3N6 Hieronymus Bosch Special Chair Radboud University Nijmegen Netherlands T: 613 533-6000, extension 78288 F: 613 533-6891 E: [email protected] Degrees: Ph.D., Groningen University, Netherlands, Department of History of Art and Architecture, 2005. Doctoral Candidacy, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, Art History Department, 1994. Master’s degree equivalent (Dutch Doctoraal Diploma), Groningen University, Netherlands, Department of History of Art and Architecture, 1993. Current affiliations: Since 2007: Professor of Art History (tenured), Department of Art History and Art Conservation, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Department Head from 2007 to 2010. Since 2010: Hieronymus Bosch Special Chair, Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands (Bijzonder Hoogleraar, 0.2 FTE). Employment history: 2006-2007: Research Curator, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 2005-2007: Lecturer on History of Art and Architecture, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. 1999-2006: Associate Curator for Research, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 2004: Lecturer, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Groningen University, Netherlands. 1997-1999: Research Associate for Technical Studies, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 1996-1997: Andrew W. Mellon Research Fellow, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. 1995-1996: Special Conservation Intern, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge MA, USA. -

Fine Art Connoisseur

FRANK MYERS BOGGS | JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME | MAINE’S ART | RACKSTRAW DOWNES | D. JEFFREY MIMS THE PREMIER MAGAZINE FOR INFORMED COLLECTORS AUGUST 2010 $8.95 U.S. | $9.95 CAN. Volume 7, Issue 4 Reprinted with permission from: TODAY ’S MASTERS ™ 800.610.5771 or International 011-561.655.8778. M CLICK TO SUBSCRIBE Caput Mundi (Capital of the World) By D. JEFFREY MIMS GH Editor’s Note: Born in North Carolina in 1954, D. Jeffrey Mims attended the Rhode Island THE FAÇADE OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME School of Design and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. After using a grant from the Elizabeth T. Greenshields Foundation to copy masterworks in European museums, he stud - ied in Florence with the muralist Benjamin F. Long IV. For more than a decade, Mims main - tained studios in Italy and North Carolina, undertaking such major projects as a fresco for Holy Trinity Episcopal Church (Glendale Springs, NC), an altarpiece for St. David’s Episcopal Church (Baltimore), and murals for Samford University in Birmingham. In 2000, he opened Mims Studios in Southern Pines, NC, offering a multi-year course in the meth - ods and values of classical realist drawing, easel painting, and mural painting. If I could have my way in the training of young artists, I should insist upon their spending a good deal of time in the study and designing of pure ornament that they might learn how in - dependent fine design is of its content and how slight may be the connection between art and nature. — Kenyon Cox (1856-1919) The Classic Point of View: Six Lectures on Painting (1911) hat artist can visit Rome and not be impressed, if not over - W whelmed, by the magnificent monumentality of the Eter - nal City? It was here that the Renaissance matured and defined itself, demonstrating the fertility of the classical tradition and setting the model for centuries of elaborations. -

Is a Filmmaker, Visual Artist, Programmer, and Writer, As Well As

is a filmmaker, visual artist, programmer, and writer, as well as a media conservation and digitization specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. Her multimedia works and films have been shown nationally, including at Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, TX, List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, Atlanta, GA, and the Studio Museum, the Maysles Cinema, and Microscope Gallery, all in New York City. Archer was previously a studio artist in the Whitney Independent Study program, a NYFA Multidisciplinary Fellow, a 2005 Creative Capital grantee in film and video, and she has been awarded numerous residencies. A contributor to Film Comment Magazine as well as other film periodicals and three blogs (Continuum Film Blog, Black Leader, Ina’s Horror Blog), she received a BA in Film/Video from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and an MA in Cinema Studies from New York University. is associate professor of comparative literature and visual studies at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she is also dean of Humanities and Arts. Since 2013 she has been a research associate in the VIAD Research Centre in the faculty of Art, Design, and Architecture at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Her areas of research span literature and philosophy, contemporary art, and photography, with a linguistic and cultural focus on French and Francophone worlds and a geographic focus on contemporary Africa. She was lead curator of C.A.O.S. (Contemporary Africa on Screen) at the South London Gallery in 2010–2011, and has been awarded fellowships from the Mellon Foundation, the Marion and Jasper Whiting Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation, and the Clark Art Institute, among others. -

Problematic Provenance: Toward a Coherent United States Policy on the International Trade in Cultural Property

COMMENTS PROBLEMATIC PROVENANCE: TOWARD A COHERENT UNITED STATES POLICY ON THE INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN CULTURAL PROPERTY MARY McKBNNA* 1. INTRODUCTION The 1980s have seen United States policy gradually retreat from the trend, traceable from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Convention of 1970 ("UNESCO Conven- tion") through the much-discussed McClain decisions1 of 1979, toward * J.D., 1990, University of Pennsylvania Law School; A.B., 1983, Harvard University. 1 The McClain case resulted in two proceedings and two appeals, United States v. McClain, 545 F.2d 988 (5th Cir. 1977), reh'g denied, 551 F.2d 52 (5th Cir. 1977), and United States v. McClain, 593 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1979). In the first appeal, the defendants were convicted of theft under the National Stolen Property Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2314, 2315 (1970 & Supp. 1990) [hereinafter NSPA], for dealing in pre-Columbian objects exported from Mexico in violation of Mexican law purporting to vest title to all such property in the Mexican government. Articulating the theory underlying the con- victions, the court reasoned that, for purposes of the NSPA, which forbids the transpor- tation in interstate commerce or the receipt of stolen goods, illegally exported artifacts subject to such a national declaration of ownership are "stolen." The second McClain appeal resulted in a reversal of the substantive NSPA conviction (although the court of appeals sustained convictions for conspiracy) on the grounds that the particular statute upon which the Mexican government based its claim was too vague to satisfy United States constitutional standards for criminal proceedings. However, the decision left open the possibility that a person might be convicted under the NSPA for conduct like that of the McClain defendants under similar circumstances. -

Graduate Programs in Art History

The CAA Directory 2017 Art History Arts Administration Curatorial & Museum GRADUATE Studies Library Science PROGRAMS Financial Aid Special Programs in art history Facilities & More 978 1 939461 44 5 INTRODUCTION iv About CAA iv Why Graduate School in the Arts v What This Directory Contains v Program Entry Contents v Admissions v Curriculum CONTENTS vi Students vi Faculty vi Resources and Special Programs vi Financial Information vii Kinds of Degrees vii A Note on Methodology GRADUATE PROGRAMS 1 Art History with Visual Studies and Architectural History 140 Arts Administration 157 Curatorial and Museum Studies 184 Library Science INDEXES 190 Alphabetical Index of Schools 191 Geographic Index of Schools ABOUT WHAT THIS DIRECTORY CONTAINS TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) score, bachelor’s degree, college transcripts, letters of recommendation, a personal Graduate Programs in Art History is a comprehensive directory of statement, foreign language proficiency, writing sample or under- programs offered primarily in the English language that grant graduate research paper, and related work experience. a graduate degree in the study of art. (For graduate programs in the practice of art, please see the companion volume, Graduate Programs in the Visual Arts.) Programs offering an advanced degree The CollegeCollege Art Association CURRICULUM WHY GRADUGRADUATEATE in art history and related disciplines are included here. This section lists information about general or specialized courses represents the professional SSCHOOLCHOOL of study, number of courses or credit hours required for gradua- interests of artists, art historians, Listings are divided into four general subject groups: tion, and other degree requirements. IN THE ARTS • Art History COURSES: Institutions usually include the number of courses museum curators, educators, (including the history of architecture and visual studies) that the department offers to graduate students each term and • Arts Administration students, and others in the United the number whose enrollment is limited to graduate students.