The Mongolian Alexander's Tomb As a Heartland: Theosophy, the Naros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Наука Красноярья Krasnoyarsk Science

ISSN 2070-7568 НАУКА КРАСНОЯРЬЯ Журнал основан в 2011 г. №6(17) 2014 Главный редактор – Я.А. Максимов Выпускающий редактор – Н.А. Максимова Ответственный секретарь редакции – О.Л. Москаленко Технический редактор, администратор сайта – Ю.В. Бяков Компьютерная верстка – Л.И. Иосипенко KRASNOYARSK SCIENCE Founded in 2011 №6(17) 2014 Editor-in-Chief – Ya.А. Maksimov Deputy Editor-in-Chief – N.А. Maksimova Executive Secretary – O.L. Moskalenko Support Contact – Yu.V. Byakov Imposer – L.I. Iosipenko Красноярск, 2014 Научно-Инновационный Центр ---- 12+ Krasnoyarsk, 2014 Publishing House Science and Innovation Center Издательство «Научно-инновационный центр» НАУКА КРАСНОЯРЬЯ, №6(17), 2014, 268 с. Журнал зарегистрирован Енисейским управлением Федеральной службы по надзору в сфере связи, информационных технологий и массовых коммуникаций (свидетельство ПИ № ТУ 24-00430 от 10.08.2011) и Международным центром ISSN (ISSN 2070-7568). Журнал выходит шесть раз в год Статьи, поступающие в редакцию, рецензируются. За достоверность сведений, изложенных в статьях, ответственность несут авторы публикаций. Мнение ре- дакции может не совпадать с мнением авторов материалов. При перепечатке ссылка на журнал обязательна. Журнал представлен в полнотекстовом формате в НАУЧНОЙ ЭЛЕКТРОННОЙ БИБЛИОТЕКЕ в целях создания Российского индекса научного цитирования (РИНЦ). Адрес редакции, издателя и для корреспонденции: 660127, г. Красноярск, ул. 9 Мая, 5 к. 192 E-mail: [email protected] http://nkras.ru/nk/ Подписной индекс в каталоге «Пресса России» – 33298 Учредитель и издатель: Издательство ООО «Научно-инновационный центр» Publishing House Science and Innovation Center KRASNOYARSK SCIENCE, №6(17), 2014, 268 p. The edition is registered (certificate of registry PE № TU 24-00430) by the Federal Service of Intercommunication and Mass Media Control and by the International cen- ter ISSN (ISSN 2070-7568). -

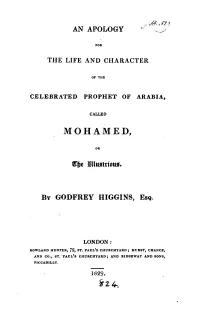

Apology for the Life and Character of Mohamed

,. ,Wx "' AN APOLOGY ~__,» THE LIFE AND CHARACTER CELEBRATED PROPHET OF ARABLM CALLED _MOHAMER I OR 'EITD8 iElllt5trf0tt§. BY GODFREY HIGGINS, ESQ. LONDON: now1.ANn uvrlnn, 72, sr. nur/s cuuncmumu; uu|v.s'r, CHANCE .mn co sr l'AUL'S cnuncmmnn; AND RIDGLWAY AND sons |>|ccA|m.|.Y 1829. 5:2/,__ » 5 )' -? -X ~.» Kit;"L-» wil XA » F '<§i3*". *> F Q' HIi PRINTED DY G. SMALLFIELIJ, HACKNEY T0 THE NOBLEMEN AND GENTLEMEN OF THE ASIATIC SO- CIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. To you, my Lords and Gentlemen, I take the liberty of dedicating this small Tract, because I am desirous of correcting what appear to me to be the erroneous opinions which some of the individuals of your Society (as well as others of my countrymen) entertain respecting the religion of many millions of the inhabitants of the Oriental Countries, about the welfare of whom you meritoriously interest your- selves; and, because a right understanding of their religion, by you, is of the first importance to their welfare. I do it without the knowledge or approba- tion of the Society, or of any of its Members, in order that they may not be implicated in my senti- ments. , » With the most sincere wishes for the welfare ot the Society, and with great respect, I remain, my Lords and Gentlemen, Your most obedient, humble servant, GODFREY HIGGINS, M. ASIAT. soc. ~ Sxznnow Gamez, NEAR Doucasrnu, July, lB29. ERRATUM. Page 80, line l§, for the " Aleph," read a Daleth, and for " H. M. A.," read IL M. D. PREFACE. -

TH-I 3-Jul-1985.Pdf

[38] JESUS IN THEOSOPHICAL HISTORY Some Theosophical leaders have taught that Jesus lived about 100 B.C., and that he was not crucified; they identify him with Jeschu Ben Pandera (the spelling varies, and will do so in this note) of Jewish tradition, who was stoned. This effectively undercuts orthodox Christianity - if there was no suffering “under Pontius Pilate”, then there was no conventional Atonement, and if the New Testament can be wrong on so important a matter as the date and manner of death of its main character then its reliability is low. The 100 B.C. theory (the precise date is sometimes given differently) was introduced by H.P. Blavatsky in “Isis Unveiled” Vol. 2 p. 201. She cites Eliphas Levi “La Science Des Esprits” (Paris, Germer Balliere, 1865, a publisher with offices in London and New York also.) Levi there printed the Jewish accounts. His book has not been translated, but it is in the S.P.R. Li- brary. Although she did not always commit herself to the theory, H.P.B. did endorse it in several places, notably in 1887 in two articles “The Esoteric Character of the Gospels” and her response in French to the Abbe Roca’s “Esotericism of Christian Dogma”. Both are in Collected Writings Vol. 8 - see especially pages, 189, 224, 380-2 and 460-1. Among scholars she cited Gerald Mas- sey in support, but added (p. 380) “Our Masters affirm the Statement.” The anti-Semitic writer Nesta H. Webster “Secret Societies and Subversive Movements” (London, 1928), quoting this same article asks “Who were the Masters whose authority Madame Blavatsky here invokes? Clearly not the Trans-Himalayan Brotherhood to whom she habitually refers by this term, and who can certainly not be suspected of affirming the authenticity of the Toldoth Yeshu. -

ROHMER, Sax Pseudoniem Van Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward Geboren: Ladywood District, Birmingham, Warwickshire, Engeland, 15 Februari 1883

ROHMER, Sax Pseudoniem van Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward Geboren: Ladywood district, Birmingham, Warwickshire, Engeland, 15 februari 1883. Overleden: White Plains, New York, USA, 1 juni 1959. Nam op 18-jarige leeftijd de naam Ward aan; gebruikte later de naam Sax Rohmer ook in het persoonlijke leven. Ander pseudoniem: Michael Furey Carrière: bracht als journalist verslag uit van de onderwereld in Londen's Limehouse; schreef liedjes en sketches voor conferenciers; woonde later in New York. Familie: getrouwd met Rose Elizabeth Knox, 1909 (foto: Fantastic Fiction). website voor alle verhalen en informatie: The Page of Fu Manchu: http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm Detective: Sir Dennis Nayland Smith Nayland Smith was voormalig hoofd van de CID van Scotland Yard en is nu in dienst van de British Intelligence. Sidekick: Dr. Petrie. Tegenspeler: Doctor Fu-Manchu Op de vraag van Petrie welke pervers genie aan het hoofd staat van de afschuwelijke geheime beweging die al zoveel slachtoffers in Europaheeft gemaakt, antwoordt Smith in ‘De geheimzinnige Dr. Fu-Manchu’: "Stel je iemand voor: lang, mager, katachtig en hoge schouders, met een voorhoofd als dat van Shakespeare en het gezicht van Satan, een kaalgeschoren schedel en langwerpige magnetiserende ogen als van een kat. Geef hem al de wrede sluwheid van een geheel Oosters ras, samengebracht in één reusachtig intellect, met alle hulpbronnen van vroegere en tegenwoordige wetenschap... Stel je dat schrikwekkende wezen voor en je hebt een krankzinnig beeld van Dr. Fu-Manchu, het Gele Gevaar, vlees geworden in één mens". Zo werd Fu-Manchu als een Chinese crimineel in 1912 in het verhaal "The Zayat Kiss" geïntroduceerd. -

Tibetan Studies in Russia: a Brief Historical Account

Annuaire de l'École pratique des hautes études (EPHE), Section des sciences religieuses Résumé des conférences et travaux 126 | 2019 2017-2018 Religions tibétaines Tibetan studies in Russia: a brief historical account Alexander Zorin Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/asr/2498 DOI: 10.4000/asr.2498 ISSN: 1969-6329 Publisher Publications de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études Printed version Date of publication: 15 September 2019 Number of pages: 63-70 ISBN: 978-2909036-47-2 ISSN: 0183-7478 Electronic reference Alexander Zorin, “Tibetan studies in Russia: a brief historical account”, Annuaire de l'École pratique des hautes études (EPHE), Section des sciences religieuses [Online], 126 | 2019, Online since 19 September 2019, connection on 06 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/asr/2498 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/asr.2498 Tous droits réservés : EPHE Religions tibétaines Alexander ZORIN Directeur d’études invité Institut des Manuscrits Orientaux, Académie des Sciences de la Russie, Saint-Pétersbourg Tibetan studies in Russia: a brief historical account IBETOLOGY is one of the oldest branches of Oriental studies in Russia that used to Tbe closely connected with foreign and inner policy of the Russian State starting from the late 17th century. The neighborhood with various Mongolian politia and gradual spread of Russian sovereignty upon some of them caused the necessity of studying and using Tibetan along with Mongolian, Oirat, Buryat languages and also, from the 18th century, studying Tibetan Buddhism as the dominant religion of these people. Huge collections of Tibetan texts and Tibetan arts were gradually gathered in St. Petersburg and some other cities, and the initiator of this process was Peter the Great, the first Russian emperor. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of the Devil Doctor, by Sax Rohmer This

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Devil Doctor, by Sax Rohmer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Devil Doctor Author: Sax Rohmer Release Date: August 29, 2006 [EBook #19142] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DEVIL DOCTOR *** Produced by David Clarke, Sankar Viswanathan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net THE DEVIL DOCTOR HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED ADVENTURES IN THE CAREER OF THE MYSTERIOUS DR. FU-MANCHU BY SAX ROHMER SIXTH EDITION METHUEN & CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON _First Published (Crown 8vo) March 2nd, 1916_ * * * * * CONTENTS CHAP. I A MIDNIGHT SUMMONS II ELTHAM VANISHES III THE WIRE JACKET IV THE CRY OF A NIGHTHAWK V THE NET VI UNDER THE ELMS VII ENTER MR. ABEL SLATTIN VIII DR. FU-MANCHU STRIKES IX THE CLIMBER X THE CLIMBER RETURNS XI THE WHITE PEACOCK XII DARK EYES LOOK INTO MINE XIII THE SACRED ORDER XIV THE COUGHING HORROR XV BEWITCHMENT XVI THE QUESTING HANDS XVII ONE DAY IN RANGOON XVIII THE SILVER BUDDHA XIX DR. FU-MANCHU'S LABORATORY XX THE CROSSBAR XXI CRAGMIRE TOWER XXII THE MULATTO XXIII A CRY ON THE MOOR XXIV STORY OF THE GABLES XXV THE BELLS XXVI THE FIERY HAND XXVII THE NIGHT OF THE RAID XXVIII THE SAMURAI'S SWORD XXIX THE SIX GATES XXX THE CALL OF THE EAST XXXI "MY SHADOW LIES UPON YOU" XXXII THE TRAGEDY XXXIII THE MUMMY * * * * * THE DEVIL DOCTOR CHAPTER I A MIDNIGHT SUMMONS "When did you last hear from Nayland Smith?" asked my visitor. -

Geography of 'The Secret History of the Mongols'

GEOGRAPHY OF ‘THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE MONGOLS’ Location of C13th Mongol Place Names and Topographical Features in NE Mongolia V. Pecchia RIBA, Dip Arch. Dip. Tp. 11/14/2010 In collaboration with the Dept. of Archaeology and Anthropology of Bristol University, Bristol, UK. [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT This paper examines the time and space relationship of events recorded in ‘The Secret History of the Mongols’ (SH) by reference to primary and secondary associated historical sources, available satellite imagery and the results of on the ground reconnaissance expeditions conducted in 2008, 2009 and 2010. The pre Chinghiss period of Temuchin’s life is irrevocably tied to NE Mongolia and in particular with the upper river basins of the rivers Kerulen and Onon, often referred to as ‘Ononkerule’, the homeland of 13th Century (C13th) Mongols. The expeditionary work carried out in this area, added to emerging historical evidence contributes significantly to the view that the SH accounts have real validity and can be geographically located. Since ‘The Secret History of the Mongols’ has become widely available in the public domain, considerable effort has been dedicated to identify the geographical locations of recorded events in the life of Temuchin. By the end of the C20th renowned Mongolists have advanced considerably the space time relationships of the pre Chinghiss Khan period of Temuchin’s life, with the geography of North East Mongolia. Notwithstanding these advances much remains to be investigated studied and tested, to dispel doubt and controversy. Definitive identification of key events, named locations and geographical features, such as the whereabouts of the Tunggelik, Tana, Sanguur Streams and Burgi Ereg (Ergi) to name some and perhaps even where Chinghiss’s sacred mountain Burkhan Khaldun is not, will significantly improve our understanding of C13th Mongol History for the benefit of the people of Mongolia and worldwide interest. -

Frontier Boomtown Urbanism: City Building in Ordos Municipality, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 2001-2011

Frontier Boomtown Urbanism: City Building in Ordos Municipality, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 2001-2011 By Max David Woodworth A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor You-tien Hsing, Chair Professor Richard Walker Professor Teresa Caldeira Professor Andrew F. Jones Fall 2013 Abstract Frontier Boomtown Urbanism: City Building in Ordos Municipality, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, 2001-2011 By Max David Woodworth Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor You-tien Hsing, Chair This dissertation examines urban transformation in Ordos, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, between 2001 and 2011. The study is situated in the context of research into urbanization in China as the country moved from a mostly rural population to a mostly urban one in the 2000s and as urbanization emerged as a primary objective of the state at various levels. To date, the preponderance of research on Chinese urbanization has produced theory and empirical work through observation of a narrow selection of metropolitan regions of the eastern seaboard. This study is instead a single-city case study of an emergent center for energy resource mining in a frontier region of China. Intensification of coalmining in Ordos coincided with coal-sector reforms and burgeoning demand in the 2000s, which fueled rapid growth in the local economy during the study period. Urban development in a setting of rapid resource-based growth sets the frame in this study in terms of “frontier boomtown urbanism.” Urban transformation is considered in its physical, political, cultural, and environmental dimensions. -

Mapping the Mongols: Depictions and Descriptions of Mongols On

Artikel/Article: Mapping the Mongols: depictions and descriptions of Mongols on medieval European world maps Auteur/Author: Emily Allinson Verschenen in/Appeared in: Leidschrift, 28.1 (Leiden 2013) 33-49 Titel uitgave: Onbekend maakt onbemind. Negatieve karakterschetsen in de vroegmoderne tijd © 2013 Stichting Leidschrift, Leiden, The Netherlands ISSN 0923-9146 E-ISSN 2210-5298 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden No part of this publication may be gereproduceerd en/of vermenigvuldigd reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de transmitted, in any form or by any means, uitgever. electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Leidschrift is een zelfstandig wetenschappelijk Leidschrift is an independent academic journal historisch tijdschrift, verbonden aan het dealing with current historical debates and is Instituut voor geschiedenis van de Universiteit linked to the Institute for History of Leiden Leiden. Leidschrift verschijnt drie maal per jaar University. Leidschrift appears tri-annually and in de vorm van een themanummer en biedt each edition deals with a specific theme. hiermee al vijfentwintig jaar een podium voor Articles older than two years can be levendige historiografische discussie. downloaded from www.leidschrift.nl. Copies Artikelen ouder dan 2 jaar zijn te downloaden can be order by e-mail. It is also possible to van www.leidschrift.nl. Losse nummers order an yearly subscription. For more kunnen per e-mail besteld worden. Het is ook information visit www.leidschrift.nl. mogelijk een jaarabonnement op Leidschrift te nemen. Zie www.leidschrift.nl voor meer informatie. Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts. -

Re-Investigating Limehouse Chinatown: Kandinsky’S 2010 Limehouse Nights and Early 20Th-Century Oriental Plays

24 Lia Wen-Ching Liang National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan Re-investigating Limehouse Chinatown: Kandinsky’s 2010 Limehouse Nights and early 20th-century Oriental Plays Kandinsky’s production of Limehouse Nights, performed in 2010, presented a story about the interwar British society seen through the eyes of Thomas Burke, a police detective named after Thomas Burke who wrote extensively about London’s Limehouse Chinatown. By examining the trends and events in the years around 1918, which were extensively referred to in Limehouse Nights, this article discusses the Chinese images emerging from both Kandinsky’s production and the plays from the early 20th century. The analysis underlines the lasting influence of earlier China-related popular entertainment on later developments in theatre as well as on the British public perception of Chinese culture at home and abroad. Limehouse Nights thus provides a contemporary refraction of the converging elements in the early 20th century that at the same time raises questions about factuality, representation and cross-cultural understanding. Lia Wen-Ching Liang is Assistant Professor at the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan. Her major research interests are contemporary British theatre, postdramatic theatre, early 20th- century theatre, and Deleuze studies.1 Keywords: Limehouse Chinatown, British inter-war theatre, musical comedy, Oriental plays, Thomas Burke, contemporary British theatre, early 20th-century theatre t is now debatable whether London’s notorious “Old Chinatown” in I Limehouse could actually have existed.2 As historian John Seed rightly points out, “[a] series of best-selling novels and short stories, several English and American movies, American comic books, radio programmes, a classic jazz number and two very different hit records brought into international currency Popular Entertainment Studies, Vol. -

DIALOGUES with the DEAD Comp

Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D1 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi DIALOGUES WITH THE DEAD Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D2 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D3 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi Dialogues with the Dead Egyptology in British Culture and Religion 1822–1922 DAVID GANGE 1 Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D4 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University press in the UK and in certain other countries # David Gange 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Negotiating Images of the Chinese: Representations of Contemporary Chinese and Chinese Americans on US Television

Negotiating Images of the Chinese: Representations of Contemporary Chinese and Chinese Americans on US Television A Thesis Submitted to School of Geography, Politics, and Sociology For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cheng Qian September, 2019 !i Negotiating Images of the Chinese: Representations of Contemporary Chinese and Chinese Americans on US Television ABSTRACT China's rise has led to increased interest in the representation of Chinese culture and identity, espe- cially in Western popular culture. While Chinese and Chinese American characters are increasingly found in television and films, the literature on their media representation, especially in television dramas is limited. Most studies tend to focus on audience reception with little concentration on a show's substantive content or style. This thesis helps to fill the gap by exploring how Chinese and Chinese American characters are portrayed and how these portrayals effect audiences' attitude from both an in-group and out-group perspective. The thesis focuses on four popular US based television dramas aired between 2010 to 2018. Drawing on stereotype and stereotyping theories, applying visual analysis and critical discourse analysis, this thesis explores the main stereotypes of the Chinese, dhow they are presented, and their impact. I focus on the themes of enemies, model minor- ity, female representations, and the accepted others. Based on the idea that the media can both con- struct and reflect the beliefs and ideologies of a society I ask how representational practice and dis- cursive formations signify difference and 'otherness' in relation to Chinese and Chinese Americans. I argue that while there has been progress in the representation of Chinese and Chinese Americans, they are still underrepresented on the screen.