This Document Has Been Produced with the Financial Assistance of the European Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kyzylorda Oblast, Kazakhstan Challenges

for Kyzylorda Oblast Youth Health Center Oblast Youth for Kyzylorda © Umirbai Tumenbayev, official photographer © Umirbai Tumenbayev, The Kyzylorda Oblast Medical Center, Kyzylorda Oblast, Kazakhstan Kyzylorda City General overview Kyzylorda Oblast (region) is situated along the summer, precipitation generally evaporates, and Syrdariya River in the south-western part of the it is only in winter that the soil receives moisture. Republic of Kazakhstan in central Eurasia. The There are many days with strong wind, and dust region covers an area of 226 000 km2 with a storms can occur in summer. The remaining part distance of 1000 km between its northernmost of the shrinking Aral Sea – the Small Aral Sea – is and southernmost borders (1). Comprising seven located in the southern part of the region. The districts and the capital city – also called Kyzylorda Aral Sea has been described as “one of the worst – the region is more than 190 years old, one of environmental disasters of the world”(2). The the oldest in the country. It borders on Aktobe salinity of the remaining water exceeds 100 g/l. Oblast in the north-west, Karaganda Oblast in In 2008, a project to construct a seawall made the north, South Kazakhstani Oblast in the south- it possible to increase the water level slowly in east, and the Republic of Uzbekistan in the south. the northern part of the Aral. Currently, the level It has a wide range of mineral resources, the of salinity is decreasing, which has resulted in most important being hydrocarbons, non-ferrous the appearance of some species of fish. -

The Aral Sea

The Aral Sea edited by David L. Alles Western Washington University e-mail: [email protected] Last Updated 2011-11-4 Note: In PDF format most of the images in this web paper can be enlarged for greater detail. 1 Introduction The Aral Sea was once the world's fourth largest lake, slightly bigger than Lake Huron, and one of the world's most fertile regions. Today it is little more than a string of lakes scattered across central Asia east of the Caspian Sea. The sea disappeared for several reasons. One is that the Aral Sea is surrounded by the Central Asian deserts, whose heat evaporates 60 square kilometers (23 sq. miles) of water from its surface every year. Second is four decades of agricultural development and mismanagement along the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers that have drastically reduced the amount of fresh water flowing into the sea. The two rivers were diverted starting in the 1960s in a Soviet scheme to grow cotton in the desert. Cotton still provides a major portion of foreign currency for many of the countries along the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers. By 2003, the Aral Sea had lost approximately 75% of its area and 90% of its pre- 1960 volume. Between 1960 and January 2005, the level of the northern Aral Sea fell by 13 meters (~ 43 ft) and the larger southern portion of the sea by 23 meters (75.5 ft) which means that water can now only flow from the north basin to the south (Roll, et al., 2006). -

Oberhänsli, H., Boroffka, N., Sorrel, P., Krivonogov, S. (2007)

Originally published as: Oberhänsli, H., Boroffka, N., Sorrel, P., Krivonogov, S. (2007): Climate variability during the past 2,000 years and past economic and irrigation activities in the Aral Sea basin. - Irrigation and Drainage Systems, 21, 3-4, 167-183 DOI: 10.1007/s10795-007-9031-5. Irrigation and Drainage Systems, 21, 3-4, 167-183, 10.1007/s10795-007-9031-5 1 Climate variability during the past 2000 years and past economic and irrigation 2 activities in the Aral Sea basin 3 4 Hedi Oberhänsli1, Nikolaus Boroffka2, Philippe Sorrel3, Sergey Krivonogov,4 5 6 1) GeoForschungsZentrum, Telegraphenberg, D-14473 Potsdam, Germany. 7 2) Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Im Dol 2-6, D-14195 Berlin, Germany. 8 3) Laboratoire "Morphodynamique Continentale et Côtière" (UMR 6143 CNRS), 9 Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, 24 rue des Tilleuls, F-14000 CAEN, France. 10 4) United Institute of Geoloy, Geophysics and Mineralogy of the Russian Academy of 11 Sciences, Siberian Division, Novosibirsk regional Center of Geoinformational 12 Technologies, Academic Koptyug prospekt 3, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia. 13 14 Abstract 15 The lake level history, here based on the relative abundance of Ca (gypsum), is used for 16 tracing past hydrological conditions in Central Asia. Lake level was close to a minimum 17 before approximately AD 300, at about AD 600, AD 1220 and AD 1400. Since 1960 the 18 lake level is lowering again. Lake water level was lowest during the 14th or early 15th 19 centuries as indicated by a coeval settlement, which today is still under water near the 20 well-dated mausoleum of Kerderi. -

Synoptic-Scale Control Over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates

JUNE 2018 ARMONETAL. 1077 Synoptic-Scale Control over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates MOSHE ARMON Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel ELAD DENTE Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, and Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel JAMES A. SMITH Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey YEHOUDA ENZEL AND EFRAT MORIN Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel (Manuscript received 23 January 2018, in final form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT Rainfall in the Levant drylands is scarce but can potentially generate high-magnitude flash floods. Rainstorms are caused by distinct synoptic-scale circulation patterns: Mediterranean cyclone (MC), active Red Sea trough (ARST), and subtropical jet stream (STJ) disturbances, also termed tropical plumes (TPs). The unique spatiotemporal char- acteristics of rainstorms and floods for each circulation pattern were identified. Meteorological reanalyses, quantitative precipitation estimates from weather radars, hydrological data, and indicators of geomorphic changes from remote sensing imagery were used to characterize the chain of hydrometeorological processes leading to distinct flood patterns in the region. Significant differences in the hydrometeorology of these three flood-producing synoptic systems were identified: MC storms draw moisture from the Mediterranean and generate moderate rainfall in the northern part of the region. ARST and TP storms transfer large amounts of moisture from the south, which is converted to rainfall in the hyperarid southernmost parts of the Levant. -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

Experimental and Numerical Study of Sharp's Shadow Zone Hypothesis on Sand Ripples Spacing and Implica- Tion for Martian Sand Ripples

Fourth International Planetary Dunes Workshop (2015) 8012.pdf Experimental and numerical study of Sharp's shadow zone hypothesis on sand ripples spacing and implica- tion for Martian sand ripples. H. Yizhaq1,2, E. Schmerler3, I. Katra3 , H. Tsoar3 and J. Kok4. 1Swiss Institute for Dryland Environmental and En- ergy Research, Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Sede Boqer Campus, 84990, Israel ([email protected]), 2The Dead Sea and Arava Science Center. Tamar Regional Council, Israel, 3The Department of Geography and Environmental Development, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, 84105, Israel, ([email protected]), ([email protected]), ([email protected]). 4Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA, ([email protected]). Introduction: Although many works have been Materials and Methdes: Quartz sand collected done on sand transport by saltation and reptation, and from the northwestern Negev dunefield (Israel) was on the formation of sand ripples, it is still unclear what used for the laboratory wind tunnel experiments on mechanism determines the linear dependence of ripples ripple morphology. The sand was taken in the sampling dimension on wind speed [1]. We thoroughly studied site in the northern Negev– Sekher (in southeren Israel) the formation of normal ripples in a wind tunnel as a sands from the upper 10 cm of the sand dunes. Com- function of grains size and wind speed. A linear rela- mon sizes of the active (loose) sand in Sekher site are tionship between the wind shear velocity and the im- at the range of 100-400 µm with modes of 150-200 pact angle of saltating grains has been found for differ- µm, which are typical of dune saltators. -

Get App BROCHURE

#EXPERIENCELIFE INTRODUCTION GROUP ADVENTURES INDEPENDENT TRIPS BAMBA BRAND KENYA, UGANDA 4 SOUTH AMERICA ASIA & RWANDA 54 SOUTH AMERICA HISTORY & PERU VIETNAM, PERU 22 TANZANIA 67 PHILOSOPHY 5 CAMBODIA & 40 56 THAILAND BOLIVIA 27 ZIMBABWE, BOLIVIA 69 BAMBA FOR INDONESIA & BOTSWANA & 6 CHILE & 57 CHILE GOOD ARGENTINA 30 PHILIPPINES 43 NAMIBIA 71 WHY TRAVEL BRAZIL SRI LANKA & SOUTH AFRICA 58 ARGENTINA, 73 WITH BAMBA 7 31 MALDIVES 44 ISRAEL & COLOMBIA & BRAZIL 75 ECUADOR 33 INDIA, NEPAL & JORDAN 59 BAMBA APP 8 TIBET 45 COLOMBIA 77 TRIP STYLES JAPAN & SOUTH EUROPE 10 CENTRAL AMERICA GALPAGAGOS & KOREA 47 ICELAND MEXICO 34 60 ECUADOR 79 CHINA, BELIZE IRELAND, 35 KYRGYZSTAN, 48 SCOTLAND & CENTRAL AMERICA & THE KAZAKHSTAN 61 GUATEMALA & SCANDINAVIA CARIBBEAN COSTA RICA 36 OCEANIA SPAIN, MEXICO, CUBA, PORTUGAL, GUATEMALA & 82 NORTH AMERICA AUSTRALIA, NEW GERMANY & 62 BELIZE ZEALAND & FIJI 49 RUSSIA USA & CANADA 37 GUATEMALA, HONDURAS & AFRICA & MIDDLE EAST CROATIA, 85 GREECE & 63 COSTA RICA MOROCCO & TURKEY EGYPT 53 PANAMA 87 TABLE OF CONTENTS IT’S TIME TO GO AND EXPLORE THE WORLD! INDEPENDENT TRIPS TRAVEL PASSES CUBA & NEPAL 108 EUROPE SOUTH AMERICA CENTRAL THAILAND, CARIBBEAN 89 AMERICA 141 MALAYSIA & ISLANDS UZBEKISTAN, ICELAND & BRAZIL, SINGAPORE 153 MONGOLIA & NORWAY 120 ARGENTINA & COSTA RICA & CHINA 109 132 NORTH AMERICA UNITED CHILE PANAMA 142 VIETNAM, CAMBODIA & USA & CANADA JAPAN KINGDOM & 153 92 110 IRELAND 121 SOUTH AMERICA THAILAND PASSES 133 NORTH AMERICA ASIA OCEANIA SPAIN & USA & CANADA PORTUGAL 122 CHILE & 146 THAILAND NEW ZEALAND, -

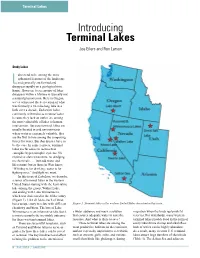

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Nutrient Dynamics in the Jordan River and Great

NUTRIENT DYNAMICS IN THE JORDAN RIVER AND GREAT SALT LAKE WETLANDS by Shaikha Binte Abedin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The University of Utah August 2016 Copyright © Shaikha Binte Abedin 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Shaikha Binte Abedin has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Ramesh K. Goel , Chair 03/08/2016 Date Approved Michael E. Barber , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved Steven J. Burian , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved and by Michael E. Barber , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In an era of growing urbanization, anthropological changes like hydraulic modification and industrial pollutant discharge have caused a variety of ailments to urban rivers, which include organic matter and nutrient enrichment, loss of biodiversity, and chronically low dissolved oxygen concentrations. Utah’s Jordan River is no exception, with nitrogen contamination, persistently low oxygen concentration and high organic matter being among the major current issues. The purpose of this research was to look into the nitrogen and oxygen dynamics at selected sites along the Jordan River and wetlands associated with Great Salt Lake (GSL). To demonstrate these dynamics, sediment oxygen demand (SOD) and nutrient flux experiments were conducted twice through the summer, 2015. The SOD ranged from 2.4 to 2.9 g-DO m-2 day-1 in Jordan River sediments, whereas at wetland sites, the SOD was as high as 11.8 g-DO m-2 day-1. -

Remodelling Global Cooperation

Global Challenges Foundation Remodelling global cooperation Global Challenges Quarterly Risk Report GLOBAL CHALLENGES QUARTERLY RISK REPORT – REMODELLING GLOBAL COOPERATION The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. Team Project leader: Carin Ism Editor-in-chief: Julien Leyre Art director: Elinor Hägg Project assistant: Elizabeth Ng Contributors Anne Marie Goetz Malini Mehra Professor, Center for Global Affairs, School Chief Executive, GLOBE International, UK of Professional Studies, New York University, USA Maria Ivanova Associate Professor of Global Governance Atangcho Nji Akonumbo and Director, Center for Governance and Associate Professor of Law, University of Sustainability, University of Massachusetts Yaoundé II/University of Bamenda, Cameroon Boston, USA Benjamin Barber Nader Khateeb Distinguished senior fellow, Fordham School Co-director, EcoPeace Middle East, Palestine of Law Urban Consortium, USA Sir Martin Rees David Held Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astro- Professor of Politics and International Rela- physics, Cambridge University, UK tions, Durham University, UK Munqeth Mehyar Folke Tersman Co-director, EcoPeace Middle East, Jordan Chair Professor of Practical Philosophy, Up- psala University, Sweden Pang Zhongying Professor, Centre for the Study of Global Gov- Gidon Bromberg ernance, School of International Studies, Ren- Co-director, EcoPeace Middle East, Israel min University, China -

Freshwater Resources

3 Freshwater Resources Coordinating Lead Authors: Blanca E. Jiménez Cisneros (Mexico), Taikan Oki (Japan) Lead Authors: Nigel W. Arnell (UK), Gerardo Benito (Spain), J. Graham Cogley (Canada), Petra Döll (Germany), Tong Jiang (China), Shadrack S. Mwakalila (Tanzania) Contributing Authors: Thomas Fischer (Germany), Dieter Gerten (Germany), Regine Hock (Canada), Shinjiro Kanae (Japan), Xixi Lu (Singapore), Luis José Mata (Venezuela), Claudia Pahl-Wostl (Germany), Kenneth M. Strzepek (USA), Buda Su (China), B. van den Hurk (Netherlands) Review Editor: Zbigniew Kundzewicz (Poland) Volunteer Chapter Scientist: Asako Nishijima (Japan) This chapter should be cited as: Jiménez Cisneros , B.E., T. Oki, N.W. Arnell, G. Benito, J.G. Cogley, P. Döll, T. Jiang, and S.S. Mwakalila, 2014: Freshwater resources. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 229-269. 229 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 232 3.1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................