Community Media Sustainability Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Research Magazine

THIS ISSUE Parking Lot Archaeology VR For Everyone Andean Peatlands Immortal Batteries MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY / 2019 SLEEP We sleep one third of our lives. Big data reveals why our hearts need plenty of sleep, which may matter more to women than men. Research TABLE OF CONTENTS 10 SLICE OF LIFE by Cyndi Perkins Industrial archaeologists uncover unexpected layers of history, ethnicities, and cultures in a small town parking lot. 12 3 PERCENT FOR THE PLANET by Kelley Christensen Peatlands cover only 3 percent of global land but store 30 percent of Earth’s soil carbon. To mitigate climate change, teams restore Andean peatlands. 16 SLEEP LAB GETS TO THE HEART OF THE MATTER by Kelley Christensen Researchers wake up to the importance of sleep for healthy hearts, especially for older women. 20 A BATTERY’S GUIDE TO IMMORTALITY by Marcia Goodrich Batteries die fast. Engineers seek battery reincarnation through ecological principles and old-school mining techniques. 24 EDUCATION ECOSYSTEM FOR STEM edited by Allison Mills Mi-STAR, Mechatronics, ETS-IMPRESS: a sustainable, empowering education ecosystem. 28 READY USER ONE by Stefanie Sidortsova This isn’t your grandpa’s typewriter. Computer scientists integrate text into virtual and augmented realities. REGULAR FEATURES 06 RESEARCH IN BRIEF 30 AWARDS 32 BEYOND THE LAB 34 RESEARCH CENTERS AND INSTITUTES Research is published by University Marketing and Communications and the Vice President for Research Office at Michigan Technological University, 1400 Townsend Drive, Houghton, Michigan, -

Reporting Facts: Free from Fear Or Favour

Reporting Facts: Free from Fear or Favour PREVIEW OF IN FOCUS REPORT ON WORLD TRENDS IN FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND MEDIA DEVELOPMENT INDEPENDENT MEDIA PLAY AN ESSENTIAL ROLE IN SOCIETIES. They make a vital contribution to achieving sustainable development – including, topically, Sustainable Development Goal 3 that calls for healthy lives and promoting well-being for all. In the context of COVID-19, this is more important than ever. Journalists need editorial independence in order to be professional, ethical and serve the public interest. But today, journalism is under increased threat as a result of public and private sector influence that endangers editorial independence. All over the world, journalists are struggling to stave off pressures and attacks from both external actors and decision-making systems or individuals in their own outlets. By far, the greatest menace to editorial independence in a growing number of countries across the world is media capture, a form of media control that is achieved through systematic steps by governments and powerful interest groups. This capture is through taking over and abusing: • regulatory mechanisms governing the media, • state-owned or state-controlled media operations, • public funds used to finance journalism, and • ownership of privately held news outlets. Such overpowering control of media leads to a shrinking of journalistic autonomy and contaminates the integrity of the news that is available to the public. However, there is push-back, and even more can be done to support editorial independence -

Girls to the Mic 2014 PDF.Pdf

Girls To The Mic! This March 8 it’s Girls to the Mic! In an Australian first, the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia’s Digital Radio Project and Community Radio Network are thrilled to be presenting a day of radio made by women, to be enjoyed by everyone. Soundtrack your International Women’s Day with a digital pop up radio station in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, and online at www.girlstothemic.org. Tune in to hear ideas, discussion, storytelling and music celebrating women within our communities, across Australia and around the world. Set your dial to Girls to the Mic! to hear unique perspectives on women in politics on Backchat from Sydney’s FBi Radio, in our communities with 3CR’s Women on the Line, seminal women’s music programming from RTR’s Drastic on Plastic from Perth, and a countdown of the top women in arts and culture from 2SER’s so(hot)rightnow with Vivid Ideas director Jess Scully. We’ll hear about indigenous women in Alice Springs with Women’s Business, while 3CR’s Accent of Women take us on an exploration of grassroots organising by women around the world. Look back at what has been a phenomenal year for women and women’s rights, and look forward to the achievements to come, with brekkie programming from Kulja Coulston at Melbourne’s RRR and lunchtime programming from Bridget Backhaus and Ellie Freeman at Brisbane’s 4EB, and an extra special Girls Gone Mild at FBi Radio celebrating the creative, inspiring and world changing women who ought to dominate the airwaves daily. -

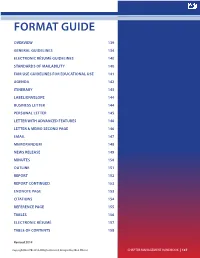

Format Guide

FORMAT GUIDE OVERVIEW 139 GENERAL GUIDELINES 134 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ GUIDELINES 140 STANDARDS OF MAILABILITY 140 FAIR USE GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATIONAL USE 141 AGENDA 142 ITINERARY 143 LABEL/ENVELOPE 144 BUSINESS LETTER 144 PERSONAL LETTER 145 LETTER WITH ADVANCED FEATURES 146 LETTER & MEMO SECOND PAGE 146 EMAIL 147 MEMORANDUM 148 NEWS RELEASE 149 MINUTES 150 OUTLINE 151 REPORT 152 REPORT CONTINUED 153 ENDNOTE PAGE 153 CITATIONS 154 REFERENCE PAGE 155 TABLES 156 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ 157 TABLE OF CONTENTS 158 Revised 2014 Copyright FBLA-PBL 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by: FBLA-PBL, Inc CHAPTER MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK | 137 138 | FBLA-PBL.ORG OVERVIEW In today’s business world, communication is consistently expressed through writing. Successful businesses require a consistent message throughout the organization. A foundation of this strategy is the use of a format guide, which enables a corporation to maintain a uniform image through all its communications. Use this guide to prepare for Computer Applications and Word Processing skill events. GENERAL GUIDELINES Font Size: 11 or 12 Font Style: Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Cambria Spacing: 1 space after punctuation ending a sentence (stay consistent within the document) 1 space after a semicolon 1 space after a comma 1 space after a colon (stay consistent within the document) 1 space between state abbreviation and zip code Letters: Block Style with Open Punctuation Top Margin: 2 inches Side and Bottom Margins: 1 inch Bulleted Lists: Single space individual items; double space between items -

Information As a Public Service

2019 ANNUAL REPORT INFORMATION AS A PUBLIC SERVICE Cover photo: A man identified as Georgy Oganezov is forcibly detained by Russian riot police in Moscow on August 3, 2019, while being interviewed on Current Time. Photo: Andrei Zolotov (MBKh Media) This report is submitted pursuant to Section 305(a) of the International Broadcasting Act of 1994 (Public Law 103-236). U.S. Agency for Global Media | 2019 Annual Report | 1 Overview and Impact ...................................2 Mission ........................................... 3 Languages ......................................... 3 Audience ..........................................4 Networks ..........................................6 Independence ......................................9 Threats to Our Journalists ............................... 10 Imprisoned and Missing Journalists ..................... 14 Transmissions and Broadcasting ......................... 16 Radio ............................................ 17 TV .............................................. 17 Digital (Web and Social Media Platforms) ................ 18 Affiliates ......................................... 18 Internet Freedom .....................................20 Providing Public Service Media .......................... 22 Impartial News Coverage ............................. 23 Unique Programming ...............................28 A Forum for Discussion .............................. 33 Reflects Underrepresented Voices ...................... 37 Media Development ...................................44 Outreach -

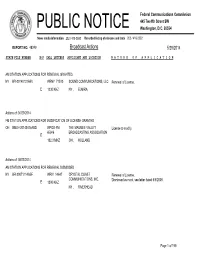

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

Part 1, 2018 – 2019 BOT June 26, 2019 at 6:30Pm Village of Jeffersonville Hall, NY Minutes Approved July 27, 2019

BOT-06-26-2019-Minutes-Part1-Approved 2 BOT-6-26-2019-packet 7 WJFF Radio Catskill Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes Annual Meeting part 1, 2018 – 2019 BOT June 26, 2019 at 6:30pm Village of Jeffersonville Hall, NY Minutes approved July 27, 2019 Trustees Present: Tim Bruno, Steve Davis, Kirsten Foster, Kathy Geary, James Lomax, Leila McCullough, Kevin McDaniel, Angela Page, Thane Peterson, Pat Pomeroy Trustees Absent: none Staff Present: Dan Rigney, Andrea Nero Eddings Members of the public present who identified themselves: Approximately 20 people in attendance A quorum being present, James Lomax called the meeting to order at 6:30 pm. Motion: To approve the minutes of the BOT meeting of May 15, 2019. (Bruno/Page). In favor: Tim Bruno, Steve Davis, Kirsten Foster, Kathy Geary, James Lomax, Leila McCullough, Kevin McDaniel, Angela Page, Thane Peterson, Pat Pomeroy Opposed: None Revision to the agenda: The matter of several board members attempting to call an emergency meeting for 6/26 at 5pm will be addressed under New Business. General Manager's Report See attached report. Programming Report See attached report. Treasurer Report Thane Peterson reports that we are on track this year for meeting the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s requirement for NFFS $300k funding with the in-kind work by BOCES volunteers being significant. We are on track to meeting our budget of $40k in Benefit income. We are also going to meet or exceed our budget of $175 in membership support. See attached Treasurer’s report and supporting financial summary reports (Budget VS Actual, etc), Vanguard investments summary, and financial policies documents. -

Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics: Smart and Digital Solutions for an Industry 4.0 Environment

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kersten, Wolfgang (Ed.); Blecker, Thorsten (Ed.); Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.) Proceedings Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics: Smart and Digital Solutions for an Industry 4.0 Environment Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), No. 23 Provided in Cooperation with: Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute of Business Logistics and General Management Suggested Citation: Kersten, Wolfgang (Ed.); Blecker, Thorsten (Ed.); Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.) (2017) : Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics: Smart and Digital Solutions for an Industry 4.0 Environment, Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), No. 23, ISBN 978-3-7450-4328-0, epubli GmbH, Berlin, http://dx.doi.org/10.15480/882.1442 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209192 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Artemis Fowl! 00:00:04 Elliott Kalan Host the Movie That Dares to Raise

00:00:00 Dan McCoy Host On this episode, we discuss: Artemis Fowl! 00:00:04 Elliott Kalan Host The movie that dares to raise the question—why is this movie named after an entirely nondescript, personality-less cipher who spends the entire movie inside his own house? 00:00:13 Music Music Light, up-tempo, electric guitar with synth instruments. 00:00:40 Dan Host Hey, everyone, and welcome to The Flop House! I’m Dan McCoy. 00:00:43 Stuart Host Hey, Dan! It’s me! Stuart Wellington! Wellington 00:00:45 Dan Host Oh hi! [Laughs.] 00:00:47 Elliott Host Guys, guys! What a coincidence! I’m Elliott Kalan and I’m here! All three hosts of The Flop House! We’re here! Together! On The Flop House! 00:00:53 Stuart Host Uh-huh. 00:00:54 Elliott Host But—we’re not alone, are we, Dan? 00:00:55 Stuart Host Uh-uh. 00:00:56 Dan Host No we’re not. We are joined by our guest Scott Weinberg, whom I did not write down how he wanted to be introduced— 00:01:05 Crosstalk Crosstalk Dan: —because I thought you were doing it, Elliott. Elliott: Oh, boy. Oh, wow. Stuart: He said it three or four times! 00:01:07 Elliott Host He said it twice, Dan. I’ll say it. Film critic. Filmmaker. Podcaster. Cat lover. Horror nerd. Scott Weinberg—and I will add in a personal—personal endorsement of his podcast, Science vs. Fiction, in which they talk about the real-life science—or fake-life science and quality—of your favorite science fiction films.