Sonia & Robert Delaunay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parcours Pédagogique Collège Le Cubisme

PARCOURS PÉDAGOGIQUE COLLÈGE 2018LE CUBISME, REPENSER LE MONDE LE CUBISME, REPENSER LE MONDE COLLÈGE Vous trouverez dans ce dossier une suggestion de parcours au sein de l’exposition « Cubisme, repenser le monde » adapté aux collégiens, en Un autre rapport au préparation ou à la suite d’une visite, ou encore pour une utilisation à distance. réel : Ce parcours est à adapter à vos élèves et ne présente pas une liste d’œuvres le traitement des exhaustive. volumes dans l’espace Ce dossier vous propose une partie documentaire présentant l’exposition, suivie d’une sélection d’œuvres associée à des questionnements et à des compléments d’informations. L’objectif est d’engager une réflexion et des échanges avec les élèves devant les œuvres, autour de l’axe suivant « Un autre rapport au réel : le traitement des volumes dans l’espace ». Ce parcours est enrichi de pistes pédadogiques, à exploiter en classe pour poursuivre votre visite. Enfin, les podcasts conçus pour cette exposition vous permettent de préparer et d’approfondir in situ ou en classe. Suivez la révolution cubiste de 1907 à 1917 en écoutant les chroniques et poèmes de Guillaume Apollinaire. Son engagement auprès des artistes cubistes n’a jamais faibli jusqu’à sa mort en 1918 et a nourri sa propre poésie. Podcasts disponibles sur l’application gratuite du Centre Pompidou. Pour la télécharger cliquez ici, ou flashez le QR code situé à gauche. 1. PRÉSENTATION DE L’EXPOSITION L’exposition offre un panorama du cubisme à Paris, sa ville de naissance, entre 1907 et 1917. Au commencement deux jeunes artistes, Georges Braque et Pablo Picasso, nourris d’influences diverses – Gauguin, Cézanne, les arts primitifs… –, font table rase des canons de la représentation traditionnelle. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Groups 3 and 6 David Sequeira Cubism and Expressionism Gallery

Groups 3 and 6 David Sequeira Cubism and Expressionism Gallery Sonia Delaunay DUBONNET 1914. Look at the work for a minute or so in silence. COLOUR (our eye follows the colours) and MOVEMENT. Largely secondary colours – (plum) red . Blue (ultramarine) . Yellow (mustardy) . Subtle contrasts . Rainbow palette . Appear to be spontaneous but carefully organised and balanced. e.g. red Geometry in the movement – circular but last quarter is different in colour and shape giving a fixed or static feel. “O” drops down, D and B also move. The “U” is like a wineglass (full). Two “N”s are Russian(?) Painting is joyful, happy, carefree (and yet so careful and contrived) celebratory, a sense of kicking up the heels. It is also hopeful, energetic, creating a feeling of change and excitement. The word Dubonnet is rhythmic. The jingle for the drink was Du beau, du bon, dubonnet…….. We do not really need to know what the word means as it is not really the focus. The painting is not a poster but it may well be an advertisement for the Delaunay’s studio itself – Aetelier “Simultane” which they established. They were intrigued by the notion of simultaneity – esp. of colours and the effects achieved. (Seurat and mixed colours). Friends and colleagues created the Orphism movement around them but they did not accept this label. Sonia came to Paris from Russia in 1905 as a young woman still in her teens. She had been brought up by a wealthy Uncle in St.Petersburg. In 1908 she made a marriage of convenience to a gay art dealer, Wilhem Uhde, who introduced her to “everyone” in the avant garde. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Jean METZINGER (Nantes 1883 - Paris 1956)

Jean METZINGER (Nantes 1883 - Paris 1956) The Yellow Feather (La Plume Jaune) Pencil on paper. Signed and dated Metzinger 12 in pencil at the lower left. 315 x 231 mm. (12 3/8 x 9 1/8 in.) The present sheet is closely related to Jean Metzinger’s large painting The Yellow Feather, a seminal Cubist canvas of 1912, which is today in an American private collection. The painting was one of twelve works by Metzinger included in the Cubist exhibition at the Salon de La Section d’Or in 1912. One of the few paintings of this period to be dated by the artist, The Yellow Feather is regarded by scholars as a touchstone of Metzinger’s early Cubist period. Drawn with a precise yet sensitive handling of fine graphite on paper, the drawing repeats the multifaceted, fragmented planes of the face in the painting, along with the single staring eye, drawn as a simple curlicue. The Yellow Feather was one of several Cubist paintings depicting women in fashionable clothes, and with ostrich feathers in their hats, which were painted by Metzinger in 1912 and 1913. Provenance: alerie Hopkins-Thomas, Paris Private collection, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, until 2011. Literature: Jean-Paul Monery, Les chemins de cubisme, exhibition catalogue, Saint-Tropez, 1999, illustrated pp.134-135; Anisabelle Berès and Michel Arveiller, Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2006, pp.428-429, no.180. Artist description: Trained in the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, Jean Metzinger sent three paintings to the Salon des Indépendants in 1903 and, having sold them, soon thereafter settled in Paris. -

The Museum of Modern Art [1 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

The Museum of Modern Art [1 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modemart NO. 32 FOR RELEASE: APRIL 22, 1975 FIVE RECENT ACQUISITIONS The first oil painting by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) to enter a museum collection in New York City will go on view at The Museum of Modern Art April 22 in a show of Five Recent Acquisitions. The Storm, painted in 1893, is from a period universally agreed to be superior to Munch1s twentieth-century work in both pictorial and psychological values. Not more than one or two such paintings are still to be found in private hands and thus available to any museum outside Norway which, for some time, has forbidden their export. "This acquisitions show of works by Munch, Laurencin, Bonnard, Matisse and Rouault is distinguished not only by its quality but by the fact that each of the five pictures was purchased or solicited as a gift in order to fill a particular need or lacuna in the Museum Collection," according to William Rubin, Director of the Museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture. The exhibition, on view through June 22, complements the showing of new acquisitions by contemporary painters incorporated last autumn in adjacent galleries where work dating from the 1950s is regularly on view. Two Women (c. 1935) by Marie Laurencin, a fine example of her middle style, is the first painting by this outstanding twentieth-century woman artist to enter The Museum of Modern Art Collection, Three other acquisitions, Bonnard's Still Life (1946), Rouault's Calvary (1930), and Matisse's Notre-Dame (1914), fill par ticular needs in the Museum's already outstanding collection of works by these artists. -

Marie Laurencin Nahmad Projects (1).Pages

Press Release - 29.01.20 7 FEBRUARY - 9 APRIL 2020 PRIVATE VIEW: 6 FEBRUARY 2020, 6-8 PM Alexander Liberman, Marie Laurencin, 1949 Nahmad Projects is pleased to announce an exhibition of paintings by Marie Laurencin, the first solo presentation of her work in London since 1947. This selection of works demonstrates the genius in Laurencin's vision of a self-sufficient world of female affection and creativity. This exhibition seeks to celebrate Marie Laurencin’s qualities as a great modernist painter, her instrumental role in defining the Art Deco style, and her influence on a generation of the Parisian intellectual elite. As a young artist, Laurencin rose quickly as a prominent figure within the Cubists. She sold her first painting to Gertrude Stein and exhibited with Cubist group the Section d’Or in 1911. Yet her friendship with male artists and romance with Guillaume Apollinaire occluded historians’ ability to recognise her contribution to modernism. Many, including those closest to her, celebrated her feminine touch but balked at the notion of equal standing with her fellow male artists. Some, however, did notice her. Henri Matisse said of Laurencin in relation to her earlier connection with the Fauvist group: “She, at least, is no mere Fauvette.” Nahmad Projects - 2 Cork St, W1S 3LB +44 020 7494 2577 Press Release - 29.01.20 Marie Laurencin’s work is canonical in the history of twentieth-century painting, with contemporary art historian Elizabeth Otto hailing the artist as a “heroine of modernism” for giving form to female independence and to lesbian love and desire. -

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, 1900-45 by Owen HEATHCOTE and DAVID Loose LEY, Lecturersinfrenchstudiesat the University Ofbradford

French Studies THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, 1900-45 By OwEN HEATHCOTE and DAVID LoosE LEY, LecturersinFrenchStudiesat the University ofBradford I. EssAYs, STUDIES Angles, Circumnavigations, posthumously reprints articles on, among others, Alain, Aragon, Claudel, Copeau, Drieu la Rochelle, Du Bos, Fernandez, Gide, Giono, Larbaud, Paulhan, Riviere, Supervielle, Valery. Shari Benstock, Women of the Left Bank: Paris, rgoo-1940, Austin, Texas U.P., 5I8 pp., is an original study which, though chiefly concerned with the lives and works of American expatriates (Colette is an exception), sheds light on the modernist culture of literary Paris by investigating the contribution of women to it and the specificity of their experience within it. Claudel Studies, I 3, no. 2, I I I pp., subtitled 'Satan, Devil, or Mephistopheles?', addresses the problem of evil conceived as existing independently of the individual: A. Espiau de la Maestre on Satan in Claudel's theatre, S. Maddux on Bernanos, M. M. Nagy on Valery, C. S. Brosman on Gide, L. M. Porter on Mauriac's Les Anges noirs, P. Brady on Proust and Des vignes, M.G. Rose on Green, and B. Stiglitz on Malraux. Hommage Dicaudin is a rich volume focusing on the birth of the modern and straddling I 9th and 20th cs. Of relevance to our period are the third section, 'de !'esprit nouveau', the fourth, devoted naturally to Apollinaire, and the fifth, 'derives de l'esprit nouveau', containing pieces on the unconscious in Soupault, and on Apollinaire andjouve. Others figuring here arejammes, Cendrars, Reverdy, and Aragon. Hommages Petit•contains inidits by Green, Claude!, and Mauriac and eight articles on C. -

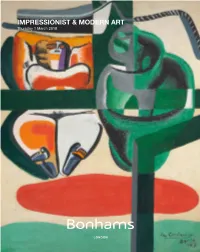

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5785 Chapter 2: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Introduction The masters, truth to tell, are judged as much by their influence as by their works. Emile Zola, 18841 Important artists are innovators: they are important because they change the way their successors work. The more widespread, and the more profound, the changes due to the work of any artist, the greater is the importance of that artist. Recognizing the source of artistic importance points to a method of measuring it. Surveys of art history are narratives of the contributions of individual artists. These narratives describe and explain the changes that have occurred over time in artists’ practices. It follows that the importance of an artist can be measured by the attention devoted to his work in these narratives. The most important artists, whose contributions fundamentally change the course of their discipline, cannot be omitted from any such narrative, and their innovations must be analyzed at length; less important artists can either be included or excluded, depending on the length of the specific narrative treatment and the tastes of the author, and if they are included their contributions can be treated more summarily. -

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House.