MORAL THEORY by John Mcmillan, Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

"Fictionalism: Morality and Metaphor"

- 1 - Fictionalism: Morality and metaphor Richard Joyce Penultimate draft of paper appearing in F. Kroon & B. Armour-Garb (eds.), Philosophical Fictionalism (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). 1. Introduction Language and reflection often pull against each other. Ordinary ways of talking appear to commit speakers to ontologies that may, upon reflection, be deemed problematic for a variety of empirical, metaphysical, and/or epistemological reasons. The use of moral discourse, for example, appears to commit speakers to the existence of obligation, evil, desert, praiseworthiness (and so on), while metaethical reflection raises a host of doubts about how such properties could exist in the world and how we could have access to them if they did. One extreme solution to the tension is to give up reflection—to become like those “honest gentlemen” of England, as Hume described them, who “being always employ’d in domestic affairs, or amusing themselves in common recreations, have carried their thoughts very little beyond those objects” (Treatise 1.4.7.14). Hume sounds a touch envious of the unreflective idyll, but the very fact that he is penning a treatise on human nature shows that this is not a solution available to him; and, likewise, the very fact that you are reading this chapter shows that it’s unlikely to be a solution for you. Another extreme solution to the tension is to give up language—not in toto, of course, but selectively: to stop using those elements of discourse that are deemed to have unacceptable commitments. How radical this eliminativism is will depend on the nature of the problem. -

The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies Linda St

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-1973 The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies Linda St. Clair Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation St. Clair, Linda, "The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies" (1973). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1028. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1028 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHIVES THE LOW-STATUS CHARACTER IN SHAKESPEAREf S CCiiEDIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bov/ling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Linda Abbott St. Clair May, 1973 THE LOW-STATUS CHARACTER IN SHAKESPEARE'S COMEDIES APPROVED >///!}<•/ -J?/ /f?3\ (Date) a D TfV OfThesis / A, ^ of the Grafduate School ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With gratitude I express my appreciation to Dr. Addie Milliard who gave so generously of her time and knowledge to aid me in this study. My thanks also go to Dr. Nancy Davis and Dr. v.'ill Fridy, both of whom painstakingly read my first draft, offering invaluable suggestions for improvement. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 THE EARLY COMEDIES 8 THE MIDDLE COMEDIES 35 THE LATER COMEDIES 8? CONCLUSION 106 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ill iv INTRODUCTION Just as the audience which viewed Shakespeare's plays was a diverse group made of all social classes, so are the characters which Shakespeare created. -

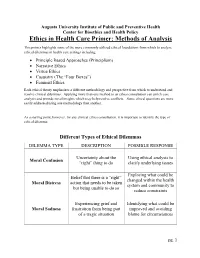

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

Shifting Liberal and Conservative Attitudes Using Moral Foundations

PSPXXX10.1177/0146167214551152Personality and Social Psychology BulletinDay et al. 551152research-article2014 Article Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Shifting Liberal and Conservative 1 –15 © 2014 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc Attitudes Using Moral Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Foundations Theory DOI: 10.1177/0146167214551152 pspb.sagepub.com Martin V. Day1, Susan T. Fiske1, Emily L. Downing2, and Thomas E. Trail3 Abstract People’s social and political opinions are grounded in their moral concerns about right and wrong. We examine whether five moral foundations—harm, fairness, ingroup, authority, and purity—can influence political attitudes of liberals and conservatives across a variety of issues. Framing issues using moral foundations may change political attitudes in at least two possible ways: (a) Entrenching: Relevant moral foundations will strengthen existing political attitudes when framing pro-attitudinal issues (e.g., conservatives exposed to a free-market economic stance) and (b) Persuasion: Mere presence of relevant moral foundations may also alter political attitudes in counter-attitudinal directions (e.g., conservatives exposed to an economic regulation stance). Studies 1 and 2 support the entrenching hypothesis. Relevant moral foundation-based frames bolstered political attitudes for conservatives (Study 1) and liberals (Study 2). Only Study 2 partially supports the persuasion hypothesis. Conservative-relevant moral frames of liberal issues increased conservatives’ liberal attitudes. Keywords morality, moral foundations, ideology, attitudes, politics Received July 1, 2013; revision accepted August 19, 2014 Our daily lives are steeped in political content, including 2012). Understanding the effectiveness of morally based many attempts to alter our attitudes. These efforts stem from framing may be consequential not only for politics but also a variety of sources, such as political campaigns, presidential for better understanding of everyday shifts in other opinions. -

Moral Rhetoric in Twitter: a Case Study of the U.S

Moral Rhetoric in Twitter: A Case Study of the U.S. Federal Shutdown of 2013 Eyal Sagi ([email protected]) Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University Evanston, IL 60208 USA Morteza Dehghani ([email protected]) Brain Creativity Institute, University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA 90089 USA Abstract rhetoric is prevalent in political debates (e.g., Marietta, 2009). In this paper we apply a computational text analysis technique used for measuring moral rhetoric in text to analyze the moral Our investigation contributes to the general study of loadings of tweets. We focus our analysis on tweets regarding moral cognition by providing an alternative method for the 2013 federal government shutdown; a topic that was at the measuring moral concerns in a more naturalistic setting forefront of U.S. politics in late 2013. Our results demonstrate compared to self-report survey method and artificial that the positions of the members of the two major political paradigms used in traditional judgment and decision-making parties are mirrored by the positions taken by the Twitter experiments. communities that are aligned with them. We also analyze retweeting behavior by examining the differences in the moral Following Sagi and Dehghani (2013), we define moral loadings of intra-community and inter-community retweets. rhetoric as “the language used for advocating or taking a We find that retweets in our corpus favor rhetoric that moral stance towards an issue by invoking or making salient enhances the cohesion of the community, and emphasize various moral concerns”. Our analysis of moral rhetoric is content over moral rhetoric. We argue that the method grounded in Moral Foundations Theory (Graham et al., proposed in this paper contributes to the general study of 2013; Haidt & Joseph, 2004), which distinguishes between moral cognition and social behavior. -

Hypatia of Alexandria A. W. Richeson National Mathematics Magazine

Hypatia of Alexandria A. W. Richeson National Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 2. (Nov., 1940), pp. 74-82. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=1539-5588%28194011%2915%3A2%3C74%3AHOA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-I National Mathematics Magazine is currently published by Mathematical Association of America. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/maa.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Nov 18 09:31:52 2007 Hgmdnism &,d History of Mdtbenzdtics Edited by G. -

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

Reason and Necessity: the Descent of the Philosopher Kings

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department 2011 Reason and Necessity: The Descent of the Philosopher Kings Damian Caluori Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Caluori, D. (2011). Reason and necessity: The descent of the philosopher kings. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 40, 7-27. This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Damian Caluori, Reason and Necessity: the Descent of the Philosopher-Kings Reason and Necessity: the Descent of the Philosopher-Kings One of the reasons why one might find it worthwhile to study philosophers of late antiquity is the fact that they often have illuminating things to say about Plato and Aristotle. Plotinus, in particular, was a diligent and insightful reader of those great masters. Michael Frede was certainly of that view, and when he wrote that ”[o]ne can learn much more from Plotinus about Aristotle than from most modern accounts of the Stagirite”, he would not have objected, I presume, to the claim that Plotinus is also extremely helpful for the study of Plato.1 In this spirit I wish to discuss a problem that has occupied modern Plato scholars for a long time and I will present a Plotinian answer to that problem. The problem concerns the descent of the philosopher kings in Plato’s Republic. -

Early Medieval G

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Religious Studies Faculty Publications Religious Studies 2001 History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval G. Scott aD vis University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/religiousstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Davis, G. Scott. "History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval." In Encyclopedia of Ethics, edited by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker, 709-15. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge, 2001. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval Copyright 2001 from Encyclopedia of Ethics by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis, LLC, a division of Informa plc. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval ''Medieval" and its cognates arose as terms of op probrium, used by the Italian humanists to charac terize more a style than an age. Hence it is difficult at best to distinguish late antiquity from the early middle ages. It is equally difficult to determine the proper scope of "ethics," the philosophical schools of late antiquity having become purveyors of ways of life in the broadest sense, not clearly to be distin guished from the more intellectually oriented ver sions of their religious rivals. This article will begin with the emergence of philosophically informed re flection on the nature of life, its ends, and respon sibilities in the writings of the Latin Fathers and close with the twelfth century, prior to the systematic reintroduction and study of the Aristotelian corpus. -

Conversational Maxim View of Politeness: Focus on Politeness Implicatures Raised in Performing Persian Offers and Invitations

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 52-58, January 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0601.07 Conversational Maxim View of Politeness: Focus on Politeness Implicatures Raised in Performing Persian Offers and Invitations Mojde Yaqubi Malay Language, Translation and Interpreting Section, School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia Karwan Mustafa Saeed School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia Mahta Khaksari Islamic Azad University, Baft Branch, Baft, Iran Abstract—This study reviewed the criticisms against Brown and Levinson’s (1987) claim about necessity of violation of cooperative principles (CP) in giving rise to politeness implicatures. To support these critiques, evidences from Persian offers and invitations were provided from the texts of 10 Iranian movies. As no alternative framework for analysing the content of these implicatures has been proposed so far, the researchers adopted two politeness principles namely ‘tact’ and ‘generosity’ maxims as well as the cost-benefit and directness-indirectness scales proposed by Leech (1983) to fill this gap in the area of Persian pragmatics. The results of this study showed that both generosity and tact maxims are the main reasons behind both direct and indirect offers and invitations. Besides, the results showed that cost-benefit scale can explain the politeness implicatures raised in performing these speech acts better than directness-indirectness scale. Index Terms—politeness implicature, offer, invitation Cooperative Principles (CP), Politeness Principles (PP), Brown and Levinson’s theory, Leech’s theory I. BACKGROUND OF STUDY Since the speech act theory has been postulated by Austin (1962) and refined by Searle (1969), it has been used in wider context in linguistics for the purpose of explaining the language use. -

The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Truth About Morality and What to Do About It, Doctoral Dissertation of Joshua D

9/03 Note to readers of The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Truth about Morality and What to Do About it, Doctoral Dissertation of Joshua D. Greene in the Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, June 2002. You are welcome to read this work, pass it on to others, and cite it. I only ask that if you pass on this work to someone else that it be passed on (1) in its entirety, (2) without modification, and (3) along with this note. I consider this a work in progress. It is currently under review in its present form at an academic press. I intend to revise and expand it substantially before publishing it as a book, so much so that the book and the dissertation will probably best be considered separate works. Comments are welcome. You can contact me by email ([email protected]) or by regular mail: Joshua Greene Department of Psychology Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544 jdg THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD TRUTH ABOUT MORALITY AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT Joshua David Greene A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY NOVEMBER 2002 © Copyright by Joshua David Greene, 2002. All rights reserved. ii Abstract In this essay I argue that ordinary moral thought and language is, while very natural, highly counterproductive and that as a result we would be wise to change the way we think and talk about moral matters. First, I argue on metaphysical grounds against moral realism, the view according to which there are first order moral truths.