Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 5. Evelyn Briggs Baldwin and Operti Bay21

48 Chapter 5. Evelyn Briggs Baldwin and Operti Bay21 Amanda Lockerby Abstract During the second Wellman polar expedition, to Franz Josef Land in 1898, Wellman’s second- in-command, Evelyn Briggs Baldwin, gave the waters south of Cape Heller on the northwest of Wilczek Land the name ‘Operti Bay.’ Proof of this is found in Baldwin’s journal around the time of 16 September 1898. Current research indicates that Operti Bay was named after an Italian artist, Albert Operti. Operti’s membership in a New York City masonic fraternity named Kane Lodge, as well as correspondence between Baldwin and Rudolf Kersting, confirm that Baldwin and Operti engaged in a friendly relationship that resulted in the naming of the bay. Keywords Franz Josef Land, historic place names, historical geography, Evelyn Briggs Baldwin, Walter Wellman, Albert Operti, Operti Bay, polar exploration, Oslo NSF workshop DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/5.3582 Background Albert Operti was born in Turin Italy and educated in Ireland and Scotland and graduated from the Portsmouth Naval School before entering the British Marine Service. He soon returned to school to study art (see Freemasons, n.d.). He came to the United States where he served as a correspondent for the New York Herald in the 1890s who accompanied Robert Peary on two expeditions to Greenland. Artwork Operti was known for his depictions of the Arctic which included scenes from the history of exploration and the ships used in this exploration in the 19th century. He painted scenes from the search for Sir John Franklin, including one of the Royal Navy vessels Erebus and Terror under sail, as well as the abandonment of the American vessel Advance during Elisha Kent Kane’s Second Grinnell expedition. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Expedition Periodicals: a Chronological List

Appendix: Expedition Periodicals: A Chronological List by David H. Stam [Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected]] THE FOLLOWING LIST provides the date, the periodical name, the setting (ship or other site), the expedition leader, the expedition name when assigned, and, as available, format and publication information. 1819–20. North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle. Hecla and Griper. William Edward Parry. British Northwest Passage Expedition. Manuscript, printed in London in 1821 with a second edition that same year (London: John Murray, 1821). Biweekly (21 issues). 1845–49. Name, if any, unknown. Terror and Erebus. Sir John Franklin. Both ships presumably had printing facilities for publishing a ship’s newspaper but no trace of one survives. [Not to be included in this list is the unpublished The Arctic Spectator & North Devon Informer, dated Monday, November 24, 1845, a completely fictional printed newssheet, invented for the Franklin Expedition by Professor Russell Potter, Rhode Island College. Only two pages of a fictional facsimile have been located.] 1850–51. Illustrated Arctic News. Resolute. Horatio Austin. Manuscript with illustrations, the latter published as Facsimile of the Illustrated Arctic News. Published on Board H.M.S. Resolute, Captn. Horatio T. Austin (London: Ackermann, 1852). Monthly. Five issues included in the facsimile. 1850–51. Aurora Borealis. Assistance. Erasmus Ommaney. Manuscript, from which selected passages were published in Arctic Miscellanies: A Souvenir of the Late Polar Search (London: Colburn and Co., 1852). Monthly. Albert Markham was aboard Assistance and was also involved in the Minavilins, a more covert paper on the Assistance which, like its Resolute counterpart, The Gleaner, was confiscated and suppressed altogether. -

Mawson's Huts Historic Site Will Be Based

MAWSON’S HUTS HISTORIC SITE CONSERVATION PLAN Michael Pearson October 1993 i MAWSON’S HUTS HISTORIC SITE CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS 1. Summary of documentary and physical evidence 1 2. Assessment of cultural significance 11 3. Information for the development of the conservation and management policy 19 4. Conservation and management policy 33 5. Implementation of policy 42 6. Bibliography 49 Appendix 1 Year One - Draft Works Plan ii INTRODUCTION This Conservation Plan was written by Michael Pearson of the Australian Heritage Commission (AHC) at the behest of the Mawson’s Huts Conservation Committee (MHCC) and the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD). It draws on work undertaken by Project Blizzard (Blunt 1991) and Allom Lovell Marquis-Kyle Architects (Allom 1988). The context for its production was the proposal by the Mawson’s Huts Conservation Committee (a private group supported by both the AHC and AAD) to raise funds by public subscription to carry out conservation work at the Mawson’s Huts Site. The Conservation Plan was developed between July 1992 and May 1993, with comment on drafts and input from members of the MHCC Technical Committee, William Blunt, Malcolm Curry, Sir Peter Derham, David Harrowfield, Linda Hay, Janet Hughes, Rod Ledingham, Duncan Marshall, John Monteath, and Fiona Peachey. The Conservation Plan outlines the reasons why Mawson’s Huts are of cultural significance, the condition of the site, the various issues which impinge upon its management, states the conservation policy to be applied, and how that policy might be implemented. Prior to each season’s work at the Historic Site a Works Program will be developed which indicates the works to be undertaken towards the achievement of the Plan. -

British & European Paintings & Watercolours Old Master & Modern Prints

Printed Books, Maps & Documents 16 JUNE 2021 British & European Paintings & Watercolours Old Master & Modern Prints including The Oliver Hoare Collection 23 JULY 2021 Gerald Leslie Brockhurst (1890-1978). Dorette, 1932, etching on wove paper, one of 111 proofs, published May 1932, signed in pencil, plate size 234 x 187 mm (9.25 x 7.3 ins). Wright 72, vi/vi; Fletcher 72. Estimate £1500-2000 For further information or to consign please contact Nathan Winter or Susanna Winters: [email protected] [email protected] 01285 860006 PRINTED BOOKS, MAPS & DOCUMENTS 16 June 2021 commencing at 10am VIEWING: By appointment only AUCTIONEERS Nathan Winter Chris Albury John Trevers William Roman-Hilditch Mallard House, Broadway Lane, South Cerney, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 5UQ T: +44 (0) 1285 860006 E: [email protected] www.dominicwinter.co.uk IMPORTANT SALE INFORMATION: COVID-19 Please note that due to the UK government's COVID-19 lockdown restrictions currently in place for England there may be no bidding in person for this sale. Viewing for this sale is available by booked appointment only. Please check our website or contact the offices to make an appointment or for more information. All lots are fully illustrated on our website (www.dominicwinter.co.uk) and all our specialist staff are ready to provide detailed condition reports and additional images on request. We recommend that customers visit the online catalogue regularly as extra lot information and images will be added in the lead-up to the sale. CONDITION REPORTS -

The Greely Expedition Program Transcript

Page 1 The Greely Expedition Program Transcript Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "We have been lured here to our destruction. We are 24 starved men; we have done all we can to help ourselves, and shall ever struggle on, but it drives me almost insane to face the future. It is not the end that affrights anyone, but the road to be traveled to reach that goal. To die is easy; very easy; it is only hard to strive, to endure, to live. Adolphus Greely." Narrator: "I will bear true faith." Every officer in the U.S. Army swore the oath to his country, but Lieutenant Adolphus Greely embodied it. He and his 24 men were about to leave the world behind and travel to the farthest reaches of the Arctic. There, they would take part in a revolutionary scientific mission, and explore the limits of the known world. It was everything Greely could have asked for. Jim Lotz, Writer: There was fame to be gained. There was glory to be gained. And he had this very, very strong drive to make himself exceptional so that he would be recognized by the military. Narrator: The military had been Greely's salvation. As a child he had seen his father crippled and his mother's life drained away in a Massachusetts mill town, and he wanted none of it. He had escaped by volunteering for the Union, had survived the bloodiest fighting in the country's history, and led one of the first units of black troops. The Civil War left him with a deep devotion to the Republic that had rescued him from obscurity. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

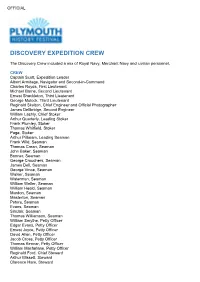

Discovery: Crew List

OFFICIAL DISCOVERY EXPEDITION CREW The Discovery Crew included a mix of Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and civilian personnel. CREW Captain Scott, Expedition Leader Albert Armitage, Navigator and Second-in-Command Charles Royds, First Lieutenant Michael Barne, Second Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, Third Lieutenant George Mulock, Third Lieutenant Reginald Skelton, Chief Engineer and Official Photographer James Dellbridge, Second Engineer William Lashly, Chief Stoker Arthur Quarterly, Leading Stoker Frank Plumley, Stoker Thomas Whitfield, Stoker Page, Stoker Arthur Pilbeam, Leading Seaman Frank Wild, Seaman Thomas Crean, Seaman John Baker, Seaman Bonner, Seaman George Crouchers, Seaman James Dell, Seaman George Vince, Seaman Walker, Seaman Waterman, Seaman William Weller, Seaman William Heald, Seaman Mardon, Seaman Masterton, Seaman Peters, Seaman Evans, Seaman Sinclair, Seaman Thomas Williamson, Seaman William Smythe, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Petty Officer Ernest Joyce, Petty Officer David Allan, Petty Officer Jacob Cross, Petty Officer Thomas Kennar, Petty Officer William Macfarlane, Petty Officer Reginald Ford, Chief Steward Arthur Blissett, Steward Clarence Hare, Steward OFFICIAL Dowsett, Steward Gilbert Scott, Steward Roper, Cook Brett, Cook Charles Clarke, 2nd Cook Clarke, Laboratory Assistant Buckridge, Laboratory Assistant Fred Dailey, Carpenter James Duncan, Carpenter’s Mate & Shipwright Thomas Feather, Boatswain (Bosun) Miller, Sailmaker Hubert, Donkeyman SCIENTIFIC Dr George Murray, Chief Scientist (left the ship at Cape Town) Louis Bernacchi, Physicist Hartley Ferrar, Geologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, Marine Biologist Reginald Koettlitz, Doctor Edward Wilson, Junior Doctor and Zoologist . -

Southward an Analysis of the Literary Productions of the Discovery and Nimrod Expeditions to Antarctica

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) In LLEAP – Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Tesi di Laurea Southward An analysis of the literary productions of the Discovery and Nimrod Expeditions to Antarctica. Relatore Ch. Prof. Emma Sdegno Laureando Monica Stragliotto Matricola 820667 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Chapter I The History of Explorations in Antarctica 8 Chapter II Outstanding Men, Outstanding Deeds 31 Chapter III Antarctic Journals: the Models 46 Chapter IV Antarctic Journals: Scott’s Odyssey and Shackleton’s Personal Attempt 70 Chapter V The South Polar Times and Aurora Australis: Antarctic Literary Productions 107 CONCLUSION 129 BIBLIOGRAPHY 134 2 INTRODUCTION When we think about Antarctica, we cannot help thinking of names such as Roald Admunsen, Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. These names represented the greatest demonstration of human endurance and courage in exploration and they still preserve these features today. The South Pole represented an unspoilt, unknown, unexplored area for a long time, and all the Nations competed fiercely to be the first to reach the geographical South Pole. England, which displays a great history of exploration, contributed massively to the rush to the Antarctic especially in the first decade of the 20th century. The long years spent in the Antarctic by the British explorers left a priceless inheritance. First of all, the scientific fields such as meteorology, geology and zoology were tellingly improved. The study of the ice sheet allowed the scientists of the time to partly explain the phenomenon of glaciations. In addition, magnetism was still a new field to be explored and the study of phenomena such as the aurora australis and the magnetic pole as a moving spot1 were great discoveries that still influence our present knowledge. -

“A Good Advertisement for Teetotallers”: Polar Explorers and Debates Over the Health Effects of Alcohol, 1875–1904

EDWARD ARMSTON-SHERET “A GOOD ADVERTISEMENT FOR TEATOTALERS”: POLAR EXPLORERS AND DEBATES OVER THE HEALTH EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL AS PUBLISHED IN THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF ALCOHOL AND DRUGS. AUTHOR’S POST-PRINT VERSION, SEPTEMBER 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/705337 1 | P a g e “A good advertisement for teetotalers”: Polar explorers and debates over the health effects of alcohol, 1875–1904.1 Abstract: This paper examines discussions about drink and temperance on British polar expeditions around the turn of the twentieth century. In doing so, I highlight how expeditionary debates about drinking reflected broader shifts in social and medical attitudes towards alcohol. These changes meant that by the latter part of the nineteenth century, practices of expeditionary drinking could make or break the reputation of a polar explorer, particularly on an expedition that experienced an outbreak of scurvy. At the same time, I demonstrate the importance of travel and exploration in changing medical understandings of alcohol. I examine these issues through an analysis of two expeditions organized along naval lines—the British Arctic Expedition (1875–6) and the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–4)—and, in doing so, demonstrate that studying 1 I would like to thank Dr James Kneale, Dr Innes M. Keighren, and Professor Klaus Dodds for their invaluable comments on drafts of this paper. An earlier version of this paper was also presented in a seminar at the Huntington Library, California, and benefited from the comments and suggestions of those who attended. This research was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) through the TECHE doctoral training partnership and by an AHRC International Placement Scheme Fellowship at the Huntington Library.