BETEL-QUID and ARECA-NUT CHEWING 1. Exposure Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calophyllum Inophyllum L

Calophyllum inophyllum L. Guttiferae poon, beach calophyllum LOCAL NAMES Bengali (sultanachampa,punnang,kathchampa); Burmese (ph’ông,ponnyet); English (oil nut tree,beauty leaf,Borneo mahogany,dilo oil tree,alexandrian laurel); Filipino (bitaog,palo maria); Hindi (surpunka,pinnai,undi,surpan,sultanachampa,polanga); Javanese (njamplung); Malay (bentagor bunga,penaga pudek,pegana laut); Sanskrit (punnaga,nagachampa); Sinhala (domba); Swahili (mtondoo,mtomondo); Tamil (punnai,punnagam,pinnay); Thai (saraphee neen,naowakan,krathing); Trade name (poon,beach calophyllum); Vietnamese (c[aa]y m[uf]u) Calophyllum inophyllum leaves and fruit (Zhou Guangyi) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Calophyllum inophyllum is a medium-sized tree up to 25 m tall, sometimes as large as 35 m, with sticky latex either clear or opaque and white, cream or yellow; bole usually twisted or leaning, up to 150 cm in diameter, without buttresses. Outer bark often with characteristic diamond to boat- shaped fissures becoming confluent with age, smooth, often with a yellowish or ochre tint, inner bark usually thick, soft, firm, fibrous and laminated, pink to red, darkening to brownish on exposure. Crown evenly conical to narrowly hemispherical; twigs 4-angled and rounded, with plump terminal buds 4-9 mm long. Shade tree in park (Rafael T. Cadiz) Leaves elliptical, thick, smooth and polished, ovate, obovate or oblong (min. 5.5) 8-20 (max. 23) cm long, rounded to cuneate at base, rounded, retuse or subacute at apex with latex canals that are usually less prominent; stipules absent. Inflorescence axillary, racemose, usually unbranched but occasionally with 3-flowered branches, 5-15 (max. 30)-flowered. Flowers usually bisexual but sometimes functionally unisexual, sweetly scented, with perianth of 8 (max. -

The Miracle Resource Eco-Link

Since 1989 Eco-Link Linking Social, Economic, and Ecological Issues The Miracle Resource Volume 14, Number 1 In the children’s book “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein the main character is shown to beneÞ t in several ways from the generosity of one tree. The tree is a source of recreation, commodities, and solace. In this parable of giving, one is impressed by the wealth that a simple tree has to offer people: shade, food, lumber, comfort. And if we look beyond the wealth of a single tree to the benefits that we derive from entire forests one cannot help but be impressed by the bounty unmatched by any other natural resource in the world. That’s why trees are called the miracle resource. The forest is a factory where trees manufacture wood using energy from the sun, water and nutrients from the soil, and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In healthy growing forests, trees produce pure oxygen for us to breathe. Forests also provide clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities to renew our spirits. Forests, trees, and wood have always been essential to civilization. In ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq), the value of wood was equal to that of precious gems, stones, and metals. In Mycenaean Greece, wood was used to feed the great bronze furnaces that forged Greek culture. Rome’s monetary system was based on silver which required huge quantities of wood to convert ore into metal. For thousands of years, wood has been used for weapons and ships of war. Nations rose and fell based on their use and misuse of the forest resource. -

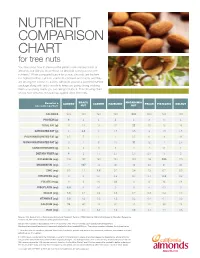

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

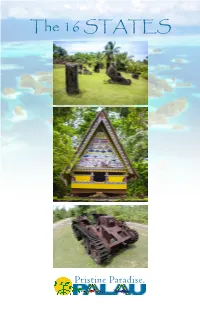

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

Uncaria Gambier Roxb) from Southeast Aceh As Antidiabetes

-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of Ethanolic Extract Gambier (Uncaria gambier Roxb) From Southeast Aceh As Antidiabetes Vera Viena1,2 and Muhammad Nizar2 {[email protected]} 1Laboratory of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, Universitas Serambi Mekkah, Aceh, Indonesia 2Department of Environmental Engineering, Universitas Serambi Mekkah, Aceh, Indonesia Abstract. Plants continue to play an important role in the treatment of diabetes. Gambier (Uncaria gambier Roxb) is one of the plants used for commercial product as a betel meal for the Acehnese. In this research we studied the inhibition activity of α-glucosidase enzyme toward gambier ethanolic extract as antidiabetes. The extraction of leaves, twigs and commercial gambier were performed by maceration method using ethanol solvent for 3 x 24 hour. Analysis of inhibition activity of α-glucosidase enzyme from each extract was done using microplate-96 well method, then the IC50 value was determined. The results showed that the inhibition activity of alpha glucosidase enzyme against gambier ethanolic extract was giving positive result, in delaying the glucose adsorption, while the highest activity was found in gambier leaves of 96,446%. The IC50 values of gambier leaves extract were compared to positive control of acarbose (Glucobay®) atwith ratio of 35,532 ppm which equal to 0,262 ppm. In conclusion, the gambier ethanolic extract has the best inhibitory activity against the alpha glucosidase enzyme to inhibite the blood sugar level, which can be used as one of traditional herbal medicine (THM) product. Keywords: α-Glukosidase, Inhibitory Activity, Gambier, Antidiabetes. 1 INTRODUCTION Metabolic disorder diseases such as Diabetes Mellitus (DM) was characterised by high blood glucose level or hyperglycemia because of insulin insufficiency and/or insulin resistance. -

A History of Fruits on the Southeast Asian Mainland

OFFPRINT A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Cambridge, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Occasional Paper 4 Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past Edited by Toshiki OSADA and Akinori UESUGI Indus Project Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan 2008 ISBN 978-4-902325-33-1 A history of Fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Cambridge, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm ABSTRACT The paper presents an overview of the history of the principal tree fruits grown on the Southeast Asian mainland, making use of data from biogeography, archaeobotany, iconography and linguistics. Many assertions in the literature about the origins of particular species are found to be without empirical basis. In the absence of other data, comparative linguistics is an important source for tracing the spread of some fruits. Contrary to the Pacific, it seems that many of the fruits we now consider characteristic of the region may well have spread in recent times. INTRODUCTION empirical base for Pacific languages is not matched for mainland phyla such as Austroasiatic, Daic, Sino- This study 1) is intended to complement a previous Tibetan or Hmong-Mien, so accounts based purely paper on the history of tree-fruits in island Southeast on Austronesian tend to give a one-sided picture. Asia and the Pacific (Blench 2005). Arboriculture Although occasional detailed accounts of individual is very neglected in comparison to other types of languages exist (e.g. -

IMS Data Reference Tables

IMS REFERENCE DATA – VERSION 1.7 TABLES 1. Substance .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Local Authority ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Drug Action Team (DAT) ...................................................................................................................................................... 13 4. Nationality ........................................................................................................................................................................... 17 5. Ethnicity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 22 6. Sexual Orientation ............................................................................................................................................................... 22 7. Religion or Belief .................................................................................................................................................................. 22 8. Employment Status .............................................................................................................................................................. 23 9. Accommodation Status -

Various Terminologies Associated with Areca Nut and Tobacco Chewing: a Review

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Vol. 19 Issue 1 Jan ‑ Apr 2015 69 REVIEW ARTICLE Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review Kalpana A Patidar, Rajkumar Parwani, Sangeeta P Wanjari, Atul P Patidar Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Modern Dental College and Research Center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Kalpana A Patidar, Globally, arecanut and tobacco are among the most common addictions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Tobacco and arecanut alone or in combination are practiced in different regions Modern Dental College and Research Centre, in various forms. Subsequently, oral mucosal lesions also show marked Airport Road, Gandhi Nagar, Indore ‑ 452 001, Madhya Pradesh, India. variations in their clinical as well as histopathological appearance. However, it E‑mail: [email protected] has been found that there is no uniformity and awareness while reporting these habits. Various terminologies used by investigators like ‘betel chewing’,‘betel Received: 26‑02‑2014 quid chewing’,‘betel nut chewing’,‘betel nut habit’,‘tobacco chewing’and ‘paan Accepted: 28‑03‑2015 chewing’ clearly indicate that there is lack of knowledge and lots of confusion about the exact terminology and content of the habit. If the health promotion initiatives are to be considered, a thorough knowledge of composition and way of practicing the habit is essential. In this article we reviewed composition and various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco habits in an effort to clearly delineate various habits. Key words: Areca nut, habit, paan, quid, tobacco INTRODUCTION Tobacco plant, probably cultivated by man about 1,000 years back have now crept into each and every part of world. -

|||||||IIIIHIIII US005411733A United States Patent 19 11 Patent Number: 5,411,733 Hozumi Et Al

|||||||IIIIHIIII US005411733A United States Patent 19 11 Patent Number: 5,411,733 Hozumi et al. 45 Date of Patent: May 2, 1995 54 ANTIVIRAL AGENT CONTAINING CRUDE 2442633 6/1980 France ......................... A61K 35/78 DRUG 2446110 8/1980 France ......................... A61K 37/02 2078753 1/1982 United Kingdom ........ A61K 35/78 76 Inventors: Toyoharu Hozumi, 30-9, 8805304 7/1988 WIPO ......................... A6K 35/78 Toyotamakita 5-chome, Nerima-ku, Tokyo; Takao Matsumoto, 1-31, OTHER PUBLICATIONS Kamiimaizumi 6-chome, Ebina-shi, Ito et al., Antiviral Research, 7, 127-137 (1987). Kanagawa; Haruo Ooyama, 89-203, Hudson, Antiviral Research, 12, 55-74 (1989). Tsurugamine 1-chome, Asahi-ku, Field et al., Antiviral Research, 2, 243-254 (1982). Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa; Tsuneo The Lancet, Mar. 28, 1981, 705–706 “Viruses and Duo Namba, 1-104, 2556-4, dena Ulcer’. Gofukusehiro-cho, Toyama-shi, Sydiskis et al. Antimircrobial Agents and Chemother Toyama; Kimiyasu Shiraki, 2-202, apy, 35(12), 2463-2466 (1991). 2556-4, Gofukusuehiro-cho, Yamamoto et al., Antiviral Research 12, 21-36 (1989). Toyama-shi, Toyama; Masao Tang et al., Antiviral Research, 13, 313-325 (1990). Hattori, 2-203, 2556-4, Fukuchi et al., Antiviral Research, 11, 285-297 (1989). Gofukusuehiro-cho, Toyama-shi, Amoros et al., Antiviral Research, 8, 13–25 (1987). Toyama; Masahiko Kurokawa, 2-101, Shiraki, Intervirology, 29, 235-240 (1988). 2-2, Minamitaikouyama, Takechi et al., Planta Medica, 42, 69-74 (1981). Kosugi-machi, Imizu-gun, Toyama; Nagai et al., Biochemical and Biophysical Research Shigetoshi Kadota, 2-402, 2556-4, Communications, 163(1), 25-31 (1989). Gofukusuehiro-cho, Toyama-shi, Ono et al., Biomed & Pharmacother, 44, 13-16 (1990). -

The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future

OIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIA The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future The Republic of Palau is located roughly 500 miles east of the Philippines in the Western Pacific Ocean. The country consists of 189 square miles of land spread over more than 340 islands, only nine of which are inhabited: 95% of the land area lies within a single reef structure that includes the islands of Babeldaob (a.k.a. Babelthuap), Peleliu and Koror. Palau and the United States have a strong relationship as enshrined in the Compact of Free Association, U.S. Public Law 99-658. Palau has made a concerted effort in goals set forth in its energy policy. recent years to address the technical, The country completed its National policy, social and economic hurdles Climate Change Policy in 2015 and Energy & Climate Facts to deploying energy efficiency and made a commitment to reduce Total capacity (2015): 40.1 MW renewable energy technologies, and has national greenhouse gas emissions Diesel: 38.8 MW taken measures to mitigate and adapt to (GHGs) as part of the United Nations Solar PV: 1.3 MW climate change. This work is grounded in Framework Convention on Climate Total generation (2014): 78,133 MWh Palau’s 2010 National Energy Policy. Change (UNFCCC). Demand for electricity (2015): Palau has also developed an energy action However with a population of just Average/Peak: 8.9/13.5 MW plan to outline concrete steps the island over 21,000 and a gross national GHG emissions per capita: 13.56 tCO₂e nation could take to achieve the energy income per capita of only US$11,110 (2011) in 2014, Palau will need assistance Residential electric rate: $0.28/kWh 7°45|N (2013 average) Arekalong from the international community in REPUBLIC Peninsula order to fully implement its energy Population (2015): 21,265 OF PALAU and climate goals. -

For Review Only

International Wound Journal Essential oils and met al ions as alternative antimicrobial agents: A focus on tea tree oil and silver Journal:For International Review Wound Journal Only Manuscript ID IWJ-15-430.R1 Wiley - Manuscript type: Original Article Keywords: Antimicrobial, Silver, Tea Tree Oil, Wound infection The increasing occurrence of hospital infections and the emerging problems posed by antibiotic resistant strains contribute to escalating treatment costs. Infection on the wound site can potentially stall the healing process at the inflammatory stage, leading to the development of acute wounds. Traditional wound treatment regime can no longer cope with the complications posed by antibiotic resistant strains; hence there is a need to explore the use of alternative antimicrobial agents. In recent research, pre- antibiotic compounds, including heavy metal ions and essential oils have been re-investigated for their potential use as effective antimicrobial Abstract: agents. Essential oils have been identified to have potent antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and other beneficial therapeutic properties. Similarly, heavy metal ions have also been used as disinfecting agents due to their broad spectrum activities. Such activities is contributed by reactive properties of the metal cations, which allows the ions to interact with many different intracellular compounds, thereby resulting in the disruption of vital cell function leading to cell death. This review will discuss the potential properties of essential oils and heavy metal ions, in particular tea tree oil and silver ions as alternative antimicrobial agents for the treatment of wounds. Page 1 of 52 International Wound Journal Abstract The increasing occurrence of hospital acquired infections and the emerging problems posed by antibiotic resistant microbial strains have both contributed to the escalating cost of treatment.